T-01. La solitude des monuments

«I monumenti debbono giganteggiare nella loro necessaria solitudine», les monuments doivent dominer dans leur solitude nécessaire (Mussolini, 1936).

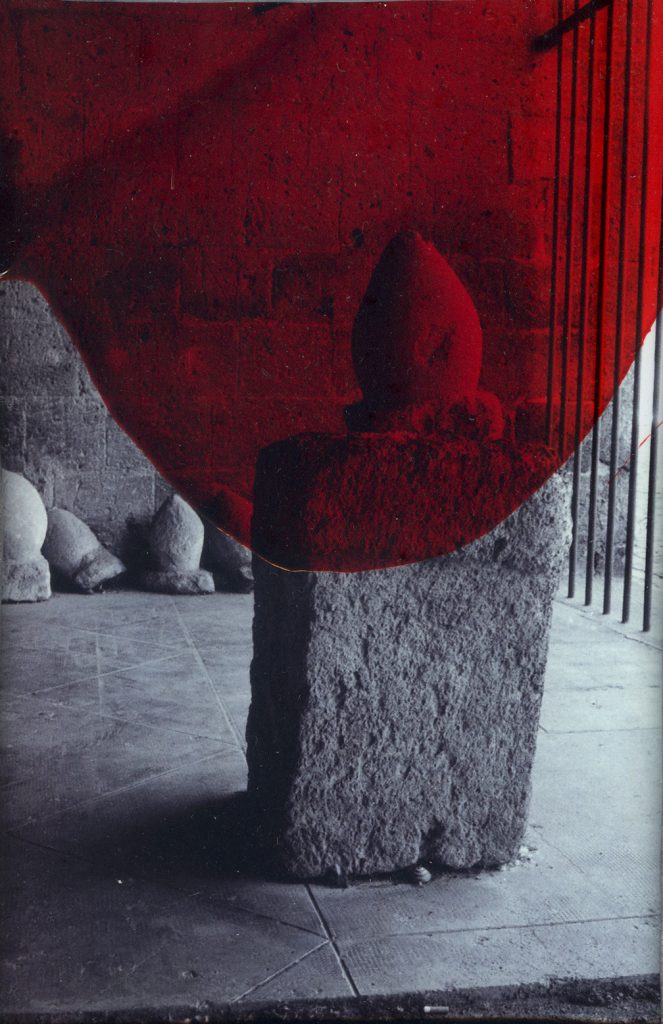

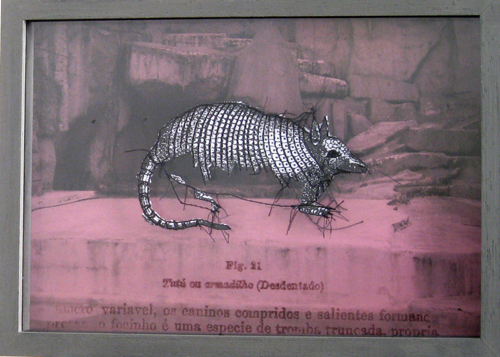

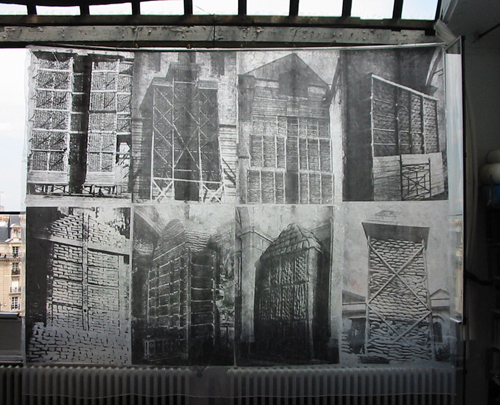

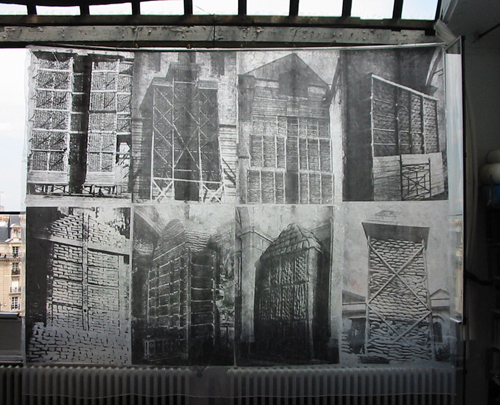

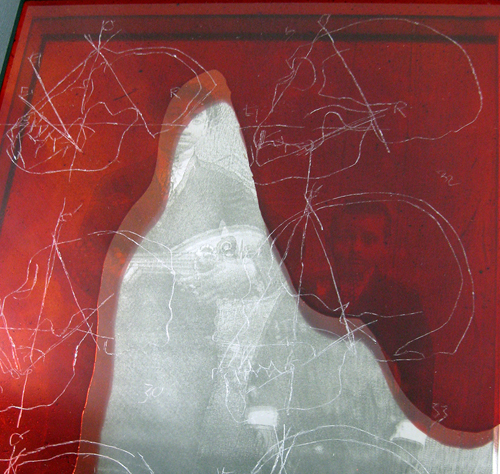

Ces images photographiques représentent des monuments et des œuvres d’art importants, abrités pendant la seconde guerre mondiale dans des architectures éphémères, en Italie. Il existe des photographies similaires pour tous les autres pays qui prirent part au conflit, ce qui nous fait imaginer à quoi devait ressembler le paysage urbain en Europe en ces années-là.

Ces emballages de briques, de sacs de sable et de couvertures matelassées, assez inefficaces en cas de bombardement direct, préservaient toutefois les fresques et les sculptures des éventuels éclats d’une explosion proche.

Dans la documentation des services du patrimoine national italien (Direzione Generale delle Arti, La protezione del patrimonio artistico nazionale dalle offese della guerra aerea, Firenze 1942) ces œuvres emprisonnées et soustraites au regard pour le bénéfice duquel elles avaient été conçues nous apparaissent dans l’état d’attente d’une catastrophe qui, par le fait même d’être ainsi annoncée, est déjà présente, et prendra parfois la forme de la dévastation qui ne fera de ces belles églises qu’un tas de débris anti-esthétiques.

La citation du discours de Mussolini que j’ai mise en exergue est un manifeste programmatique, me semble-t-il, qui peut être pris mot par mot comme une annonce de la catastrophe à venir: «monument», «dominer», «solitude», «nécessaire». C’est sur la base d’une telle conception idéologique que les édifices antiques de Rome ont été, pendant le Ventennio fasciste, «nettoyés», libérés de toute stratification et superposition historique; des quartiers d’habitation entiers (ainsi qu’une ou deux collines) ont étés rasés autour de ces monuments, pour les rendre plus visibles, pour leur attribuer un statut d’icône symbolique, à laquelle «se ressourcer».

Assez représentative de cette conception est la Tabula rasa faite autour du mausolée d’Auguste, qui reste comme une blessure insoignable en plein milieu de la ville, infligée au nom de l’équation empire romain-empire fasciste. Il fut un moment pourtant où était encore ouverte la lutte entre modernisme et post-futurisme d’un côté (assez soutenus par Mussolini, qui y voyait les réalisations de son «homme nouveau») et de l’autre côté un classicisme néo-impérial appuyé par la plupart des Gerarchi du régime. Ce conflit, qui devint explicite et public autour de 1934, se solda provisoirement par l’évident compromis du pavillon italien de l’Exposition universelle de Paris, en 1937. Mais vers la fin de la décennie les architectes rationalistes devaient désormais s’incliner devant les exigences de la représentation monumentale.

Dans les mêmes années en Allemagne il n’y avait pas vraiment de conflits esthétiques, mais on peut dire que cohabitaient d’une part une ligne officielle «dorienne» – linéaire et monumentale et très ennemie des fantaisies et des expérimentations bourgeoises et individualistes – et d’autre part un fort penchant sentimental et nostalgique d’un âge perdu. La coexistence de ces deux âmes est ce qui peut nous faire dire que le fascisme c’est le kitsch. Et ce parce que le kitsch, représentation volontariste de l’harmonie, «est une forme dégradée du mythe» (Saul Friedländler Reflets du nazisme, Paris 1982, p. 147).

Mais n’y a-t-il pas une étonnante similarité entre ces carapaces provisoires que je présente ici et les réalisations architecturales de ces deux régimes? Et pourquoi éprouvons-nous, avouons-le, une fascination pour ces formes dégradées et dégradantes?

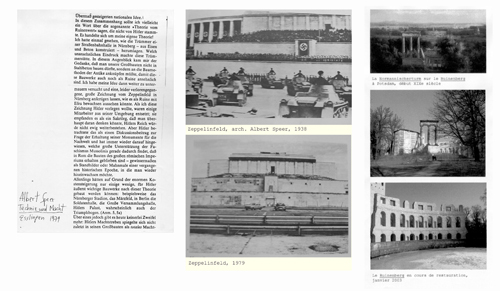

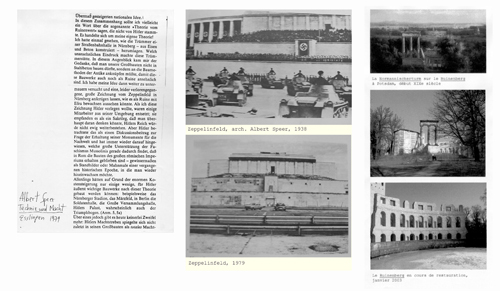

T-02. Die Ruinenwerttheorie

«Dans ce contexte, je devrais peut être consacrer quelques mots à la prétendue “Théorie de la valeur de ruine” (Theorie vom Ruinenwert), qui ne vient pas d’Hitler. Il s’agit de ma propre théorie!

J’avais eu l’occasion de voir comment les décombres d’une remise de tramways à Nuremberg, bâtie en fer et en ciment, étaient éparpillés aux alentours. Quelle impression désagréable donnait ce tas de gravats! A cette vue, je me dis que nous ne devrions pas construire nos édifices les plus importants en béton armé, mais au contraire, tirer parti des techniques de construction des Anciens, de manière à rendre de telles structures plaisantes à la vue, même une fois en ruines. A la suite de ça, j’essayai d’approfondir mes idées à ce sujet, et je réalisai un grand dessin, malheureusement perdu, du Zeppelinfeld de Nuremberg. Il ressemblait à une ruine couverte de lierre. Quand je soumis ce dessin à Hitler, certains de ses collaborateurs étaient présents; ils prirent comme un sacrilège le fait même d’imaginer que le Reich d’Hitler pouvait durer moins que l’éternité.

Mais Hitler considéra que la pérennité de ses monuments était un sujet de discussion pertinent; il savait à quel point le fascisme de Mussolini avait trouvé un grand soutien dans la présence des édifices impériaux à Rome: des icônes ou des mémoriaux d’une époque révolue dans laquelle on comptait se ressourcer.

Sans doute à cause des coûts énormes que de telles techniques de construction auraient impliqués, seuls quelques bâtiments très particuliers – d’après Hitler – pouvaient être construits suivant cette théorie: le stade de Nuremberg par exemple, les Champs de Mars et, à Berlin, la Soldatenhalle et la grande salle des rassemblements, le palais de Hitler et peut être aussi l’Arc de Triomphe.»

Albert Speer, Technik und Macht, Esslingen 1979, pp. 49-50.

En exergue à ces propos, il est peut-être intéressant de savoir que le Zeppelinfeld de Speer, « la plus grande tribune du monde », qui accueillait des défilés de 100 000 membres de son parti, est aujourd’hui – quoique dévêtu des marques les plus évidentes de sa fonction originelle comme les colonnades et l’aigle gigantesque – un parc de loisir où ont lieu des courses de voitures ou des concerts rock en plein air.

En effet, ce qui m’intéresse dans le discours de Speer c’est l’équivalence qu’il fait entre ruine et monument. Le monument a toujours un doigt pointé quelque part, il indique toujours une direction dans le temps, qu’il soit là pour souvenir (Denkmal en allemand) ou pour admonition (Mahnmal en allemand). Comme déjà le faisait remarquer Leopardi, en pleine époque romantique, dans son Zibaldone di pensieri, on édifie un monument pour contrer l’idée de finitude.

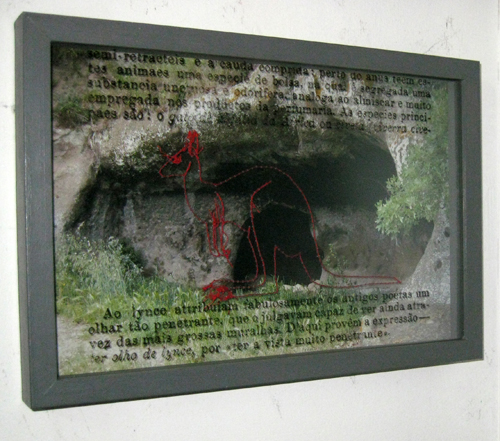

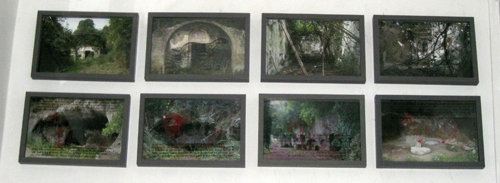

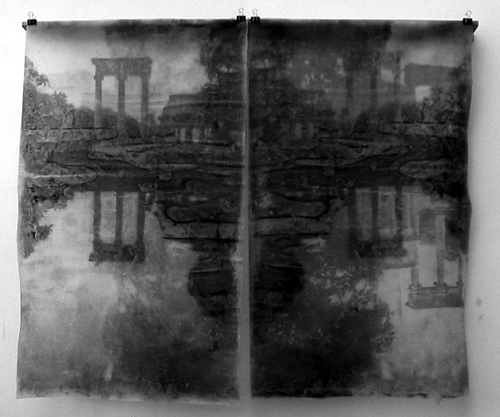

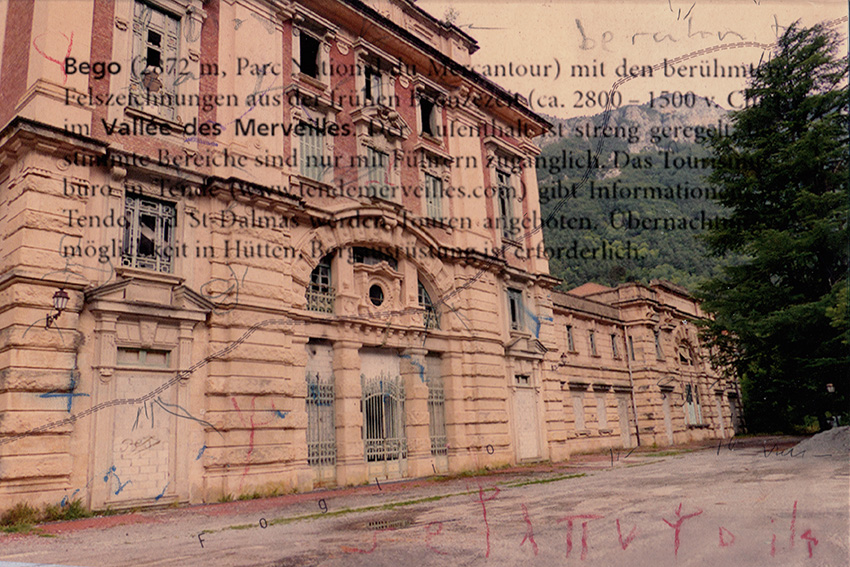

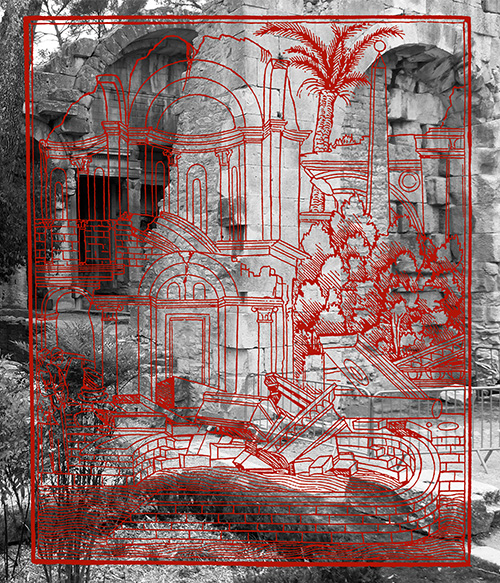

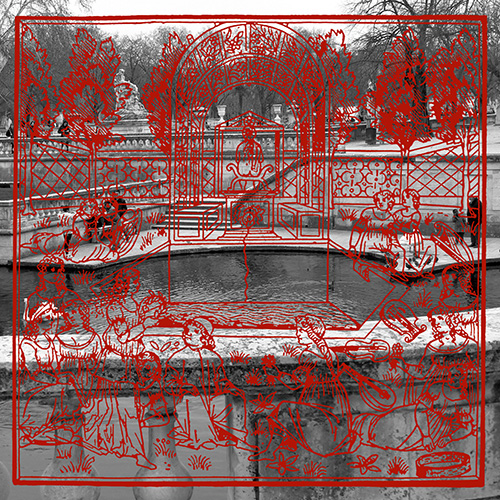

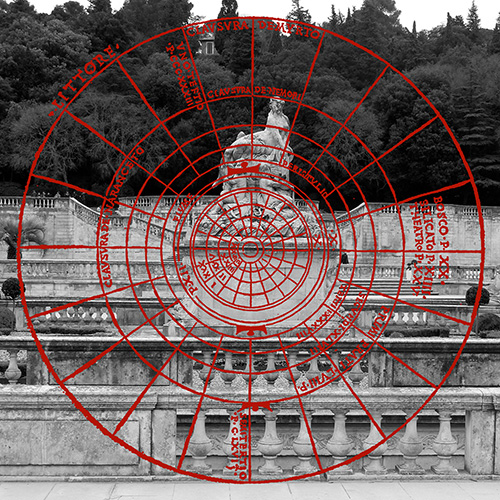

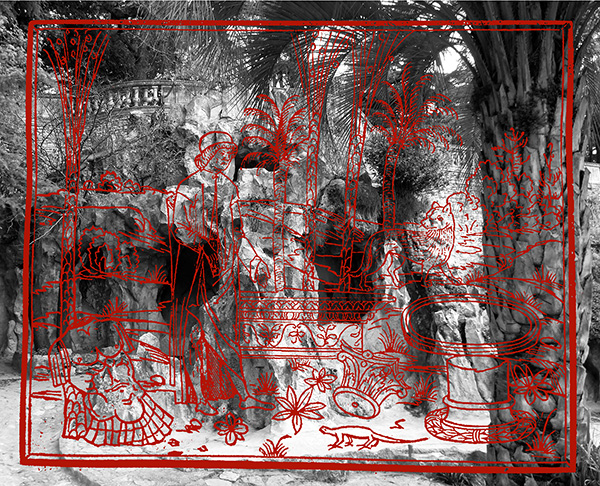

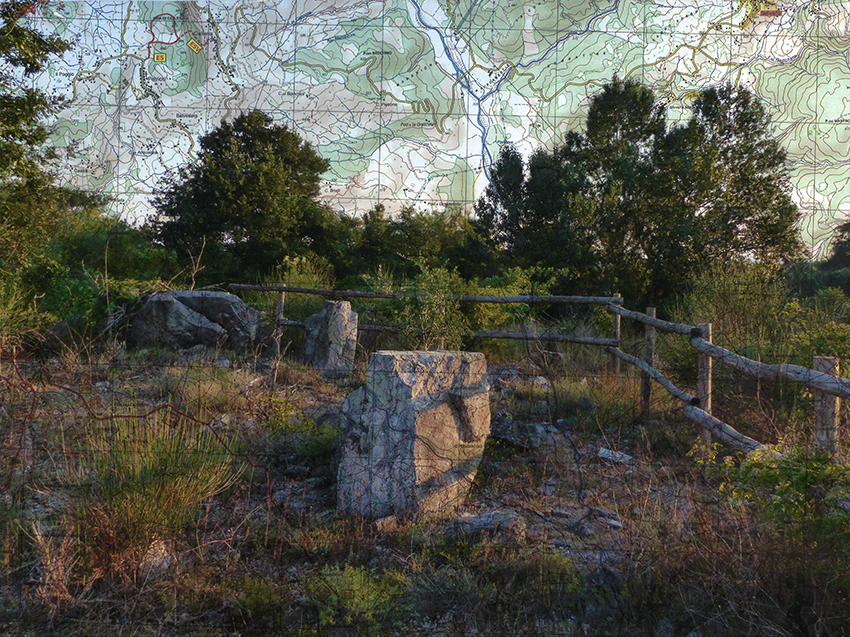

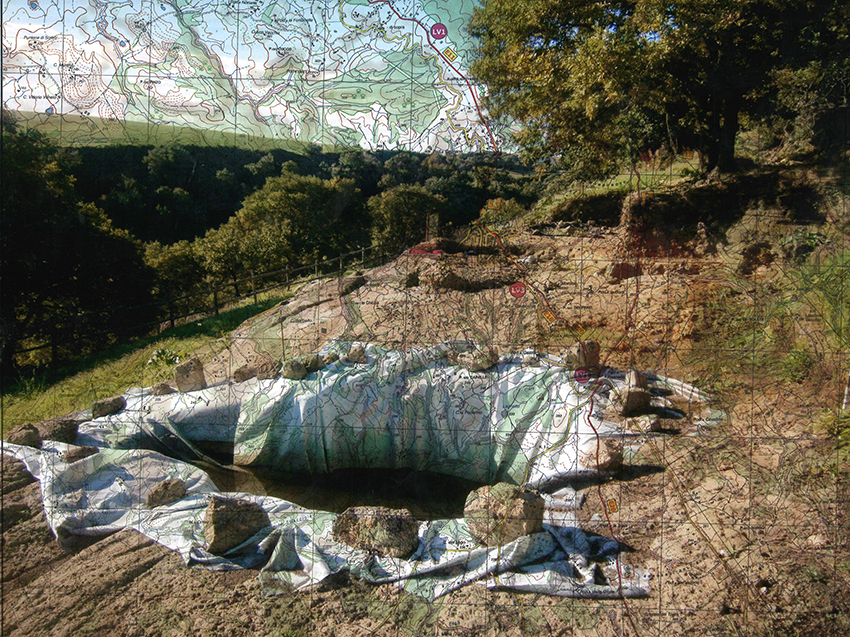

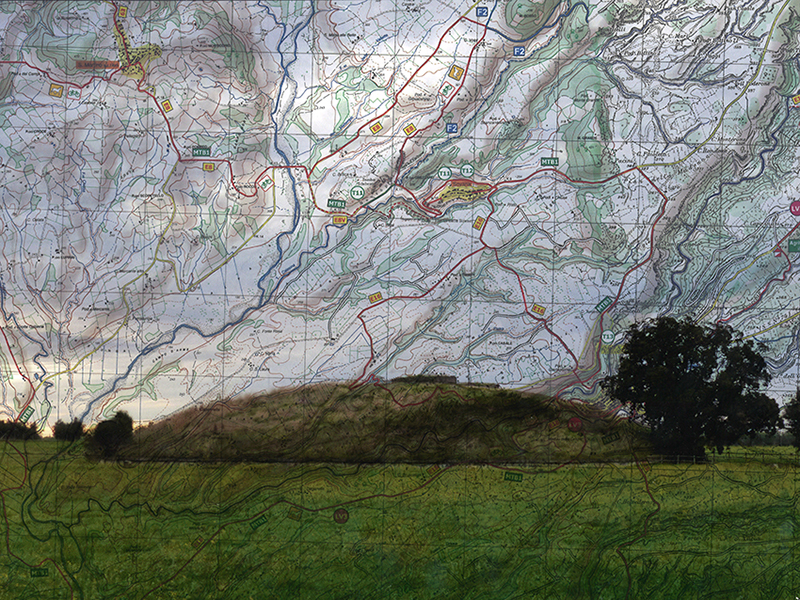

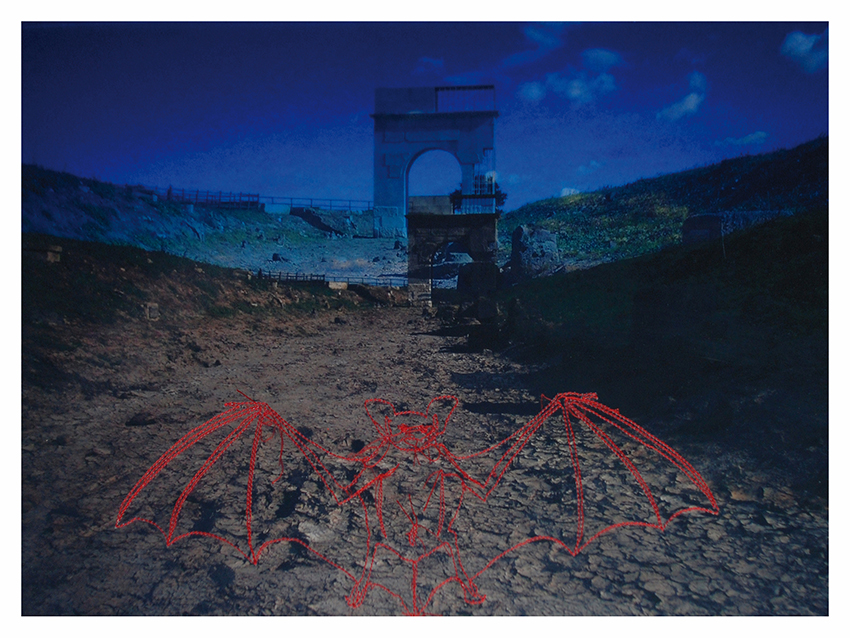

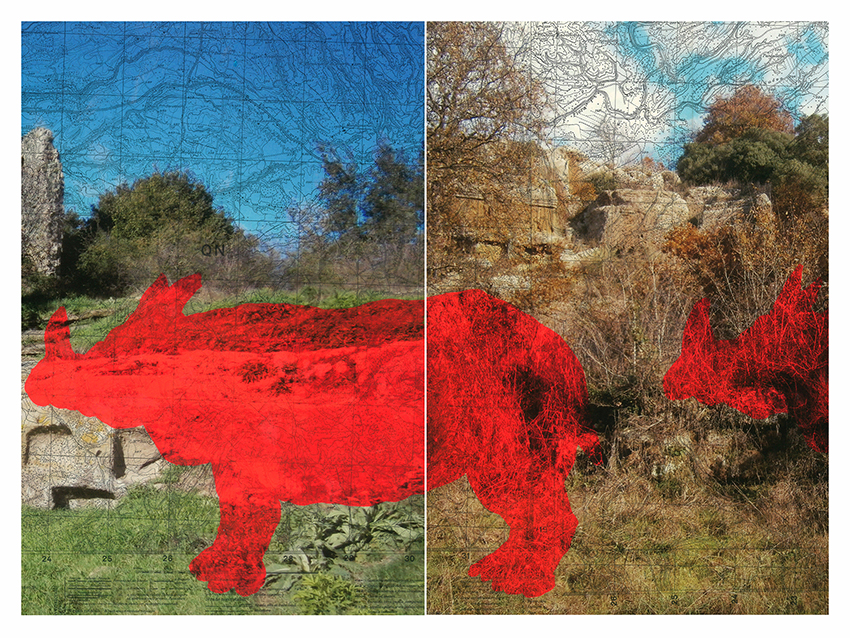

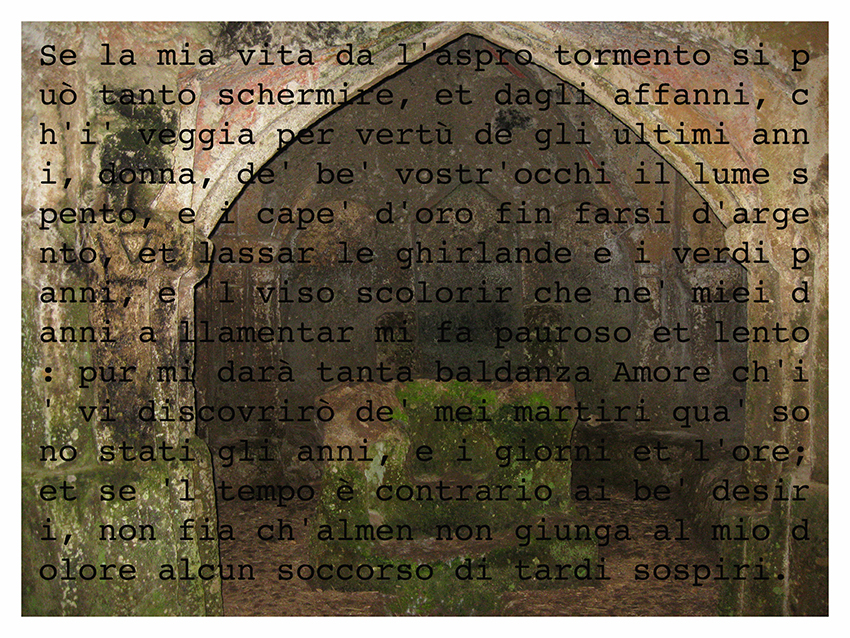

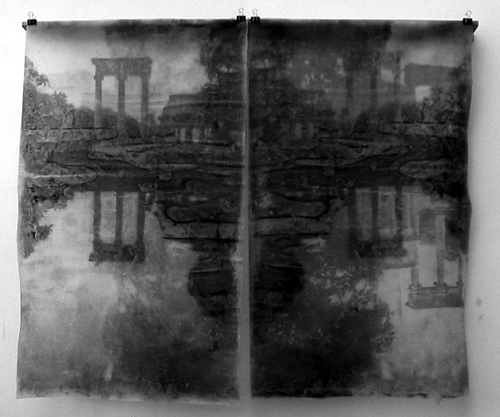

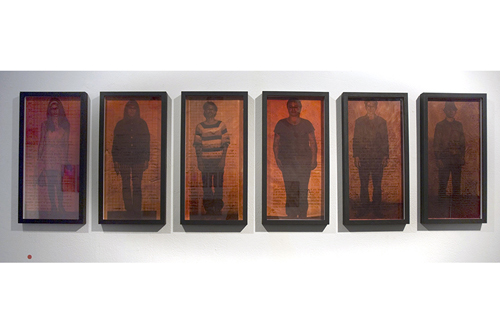

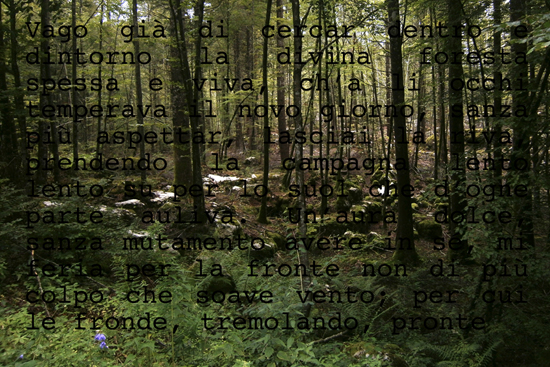

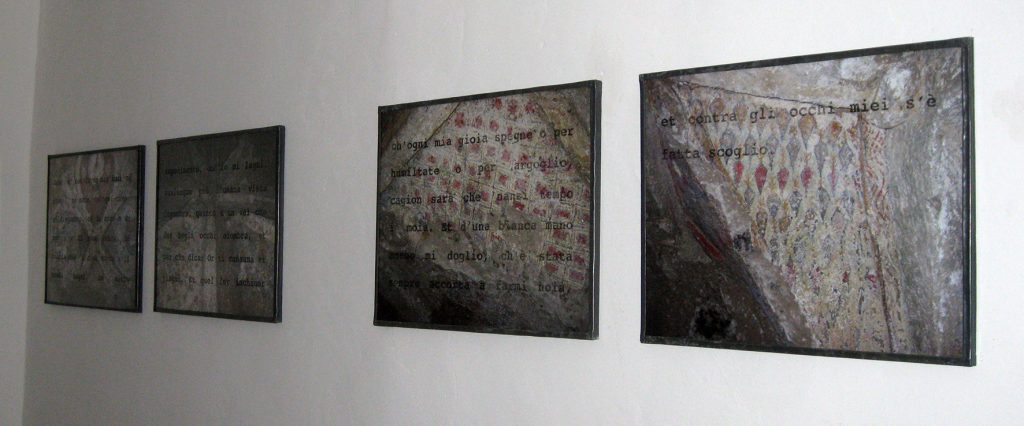

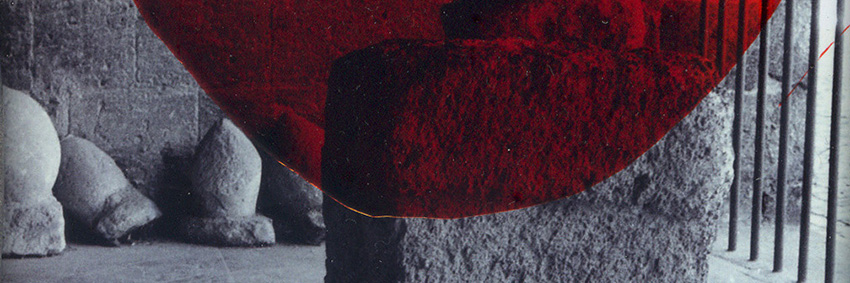

(06a-06b-06c) Je trouve intéressant de voir comment un régime à l’apogée de sa puissance peut déjà s’intéresser aux formes de sa propre chute. De mon coté, je me suis intéressé à des ruines « involontaires » : les images utilisées pour ce travail ont été prises dans trois lieux : à Rome, à l’Antiquarium comunale du Celio, un véritable cimetière en plein air pour les vestiges archéologiques qui, trop fragmentaires ou dispersés ou anonymes, n’ont pas trouvé preneur même dans les entrepôts des musées ; à Bagnoli, près de Naples, dans les bâtiments industriels désaffectés et promis à la démolition de l’Italsider ; à Potsdam, dans les parcs où les rois de Prusse bâtirent, à l’âge romantique, une forme d’identification avec l’antiquité classique.

Ces entassements de gravats sont apparemment l’antithèse de ce que Hitler et Speer entendaient par « ruine de valeur » ou « valeur de ruine ». En même temps, je ne suis pas sûr que ce qui m’a fait sauter par-dessus les grilles de ces sites pour les photographier ne soit pas une version, peut-être plus consciente ou plus « dé-construite », d’une pareille attirance pour la ruine en soi. Bien sûr, il ne s’agit pas là de la pathétique nostalgie pour un monde méditerranéen qui pouvait se prévaloir d’une histoire ancienne et d’un passé monumental, nostalgie qui poussa nombre d’aristocrates allemands à se faire construire dans les parcs de leurs châteaux des Künstliche Ruine (ruines artificielles) de bois et de plâtre peint. Mais cette fascination pour la ruine romantique, bien évidente dans le texte de Speer, et qui lui vient tout droit du XVIIIe siècle, est typique de ces êtres rationnels qui misent sur leur propre persistance dans les temps à venir. (07-08)

Quand j’ai photographié le site de la « tour normande », avec ces arcades « romaines » et son temple « grec » (c’était en 2003), j’ai trouvé assez amusant le fait que l’on soit en train de le restaurer à son état de « fausseté originelle ». Celle-ci a été ma tentative de traduction : (09a-09b)

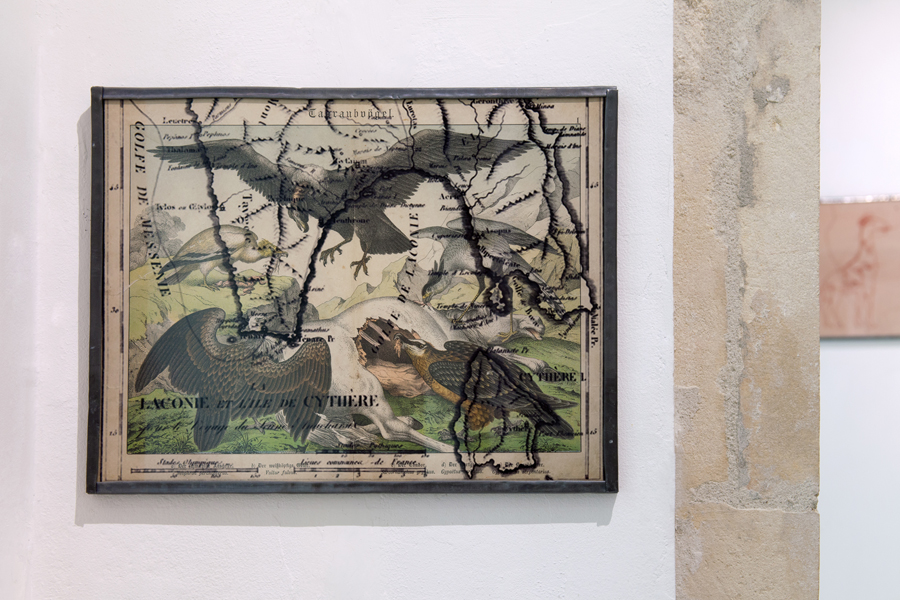

Juste à titre de parenthèse, je voudrais montrer ici quelques images illustrant une esthétique de la ruine. Il me paraît que toutes, dans leur diversité, témoignent d’une vision de la ruine comme d’un épisode dans une continuité linéaire du temps : ce sont des images „pré-benjaminiennes“. La chute n’est pas encore la catastrophe.

(10a) Un Capriccio di rovine de Giovambattista Piranesi, 1756. Je vous prie de remarquer la taille des personnages par rapport à celles des vestiges entassés.

(10b) Rovine di una galleria di statue nella Villa Adriana, de Piranesi, achevé en 1770.

(11) Le désespoir de l’artiste devant la grandeur des ruines antiques, Johann Heinrich Füssli, 1780.

(12) Vue de la grande galerie du Louvre en ruines, de Hubert Robert. Cet artiste éclairé et savant, tout en participant activement aux acquisitions et à l’aménagement du nouveau musée du Louvre, dans les années autour de 1795, se projetait déjà dans le futur.

T-03. Sentimentalisierung ist Verbrechen

«L’art ne trouve pas son fondement dans le temps, mais uniquement dans les peuples…» Hitler, 1937.

«L’artiste qui croit devoir peindre pour son temps ou pour servir le goût du temps n’a pas compris le Führer. La mise du jeu est pour l’éternité! Créer l’éternel à partir du temporel, voici le sens de toute entreprise humaine.» Baldur von Schirach, 1941.

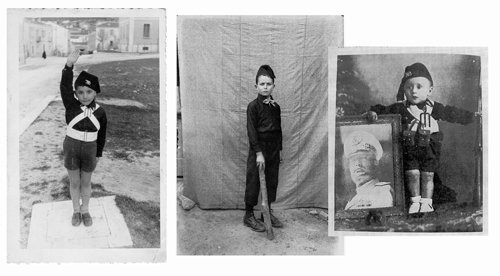

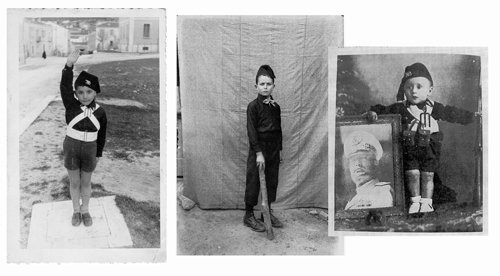

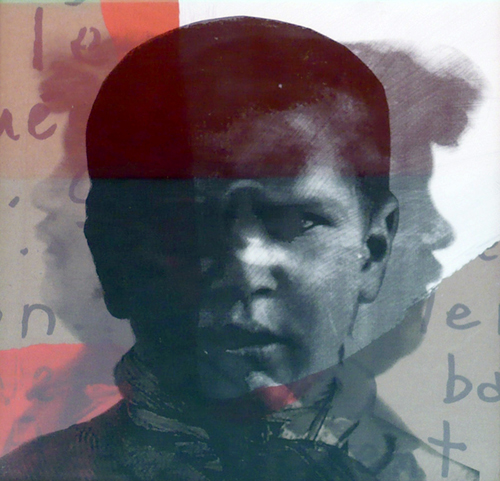

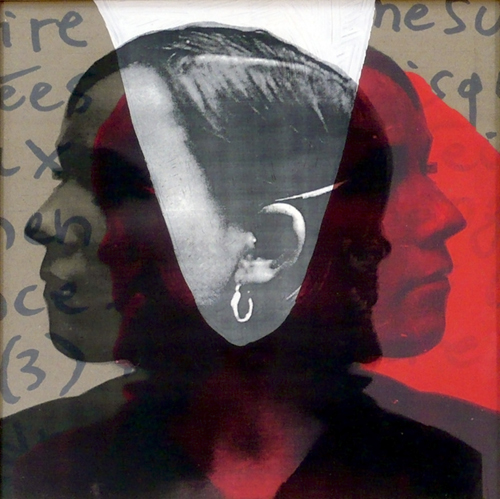

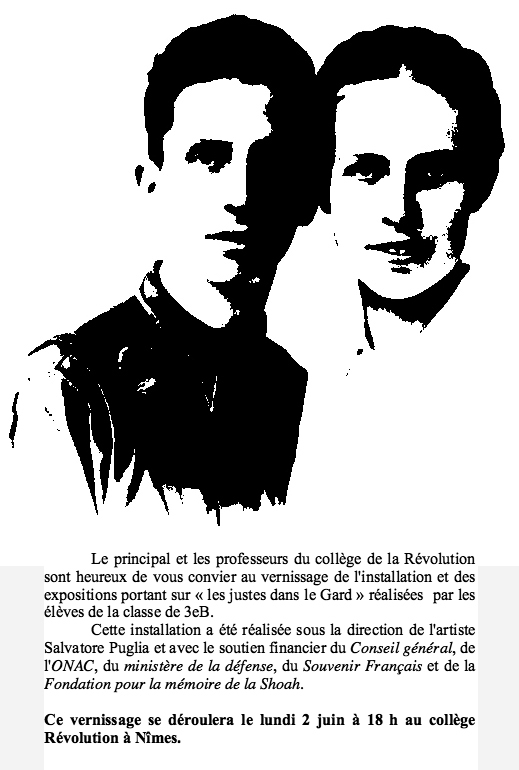

Les Balilla (du nom d’un jeune Génois qui, en lançant une première pierre, donna le signal de l’insurrection contre les occupants autrichiens, en 1746) étaient les enfants entre six et douze ans qui étaient encadrés dans les nombreux corps paramilitaires du fascisme italien (entre trois et six ans on était Figlio della Lupa; entre treize et dix-huit on était Avanguardista; à partir de dix-huit on était Giovane Italiano).

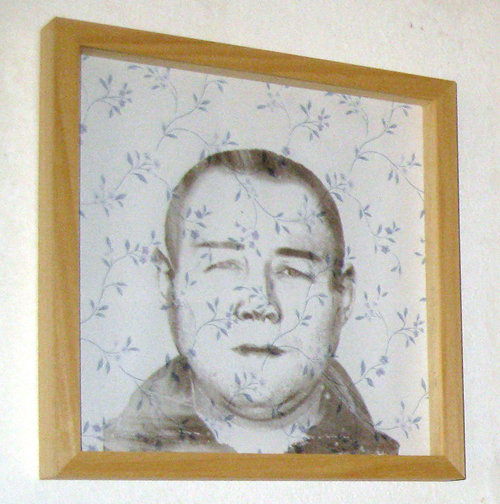

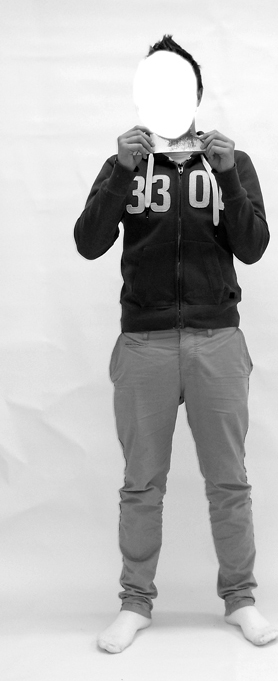

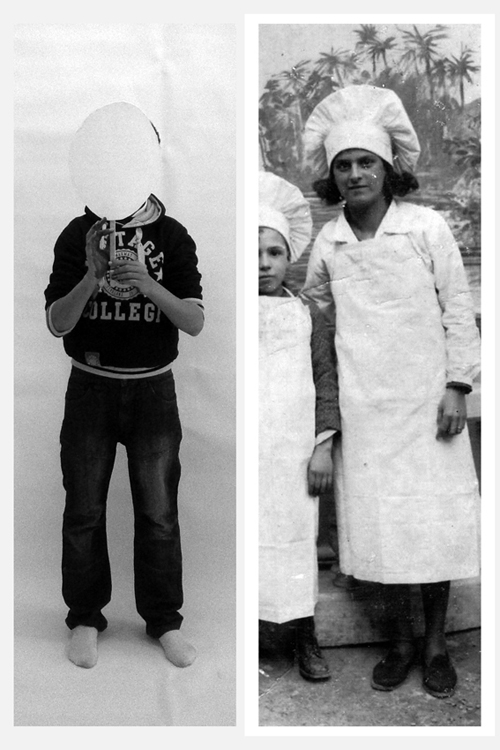

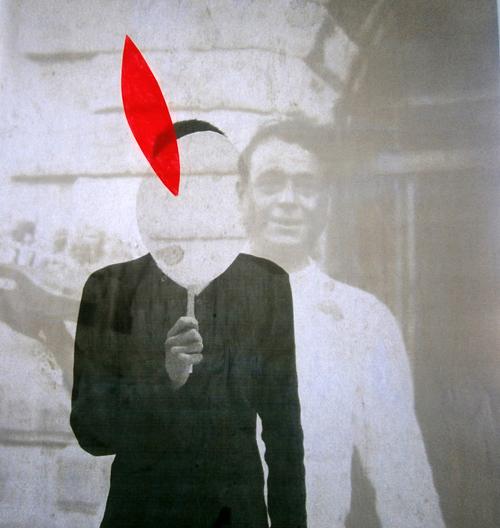

Dans la pose photographique (bien entendu, toute photographie «isole» et «iconise» son sujet) l’enfant est «promis», consigné par les adultes qui en ont la responsabilité au régime qui lui garantira le futur dans lequel il est ainsi inscrit. En témoignent les trois variantes sur le thème que nous vous proposons dans la documentation ci-jointe: enfant en uniforme qui fait le geste fasciste; enfant en uniforme avec gourdin; enfant en uniforme avec portrait du Duce.

Cette tendresse dans l’acte de placer le bambin devant l’objectif photographique, qui est finalement la même avec laquelle nous prenons nos fils en photo, est assortie d’une menace: ce gamin est déjà un soldat, et il sera dans le camp des vainqueurs. Son uniforme le protège déjà, tout en lui donnant les repères symboliques et idéologiques de sa vie d’adulte. En même temps, nous savons que ce père qui, avec toute la fierté du monde, a amené son fils au studio photographique du coin, est un Abraham qui utilise l’objectif au lieu du couteau sacrificiel: «This child is dying», dirait Chris Fynsk (Infant Figures, Stanford 2000, pp. 49-130).

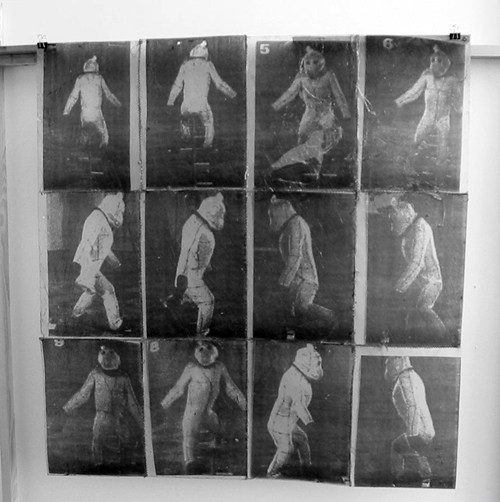

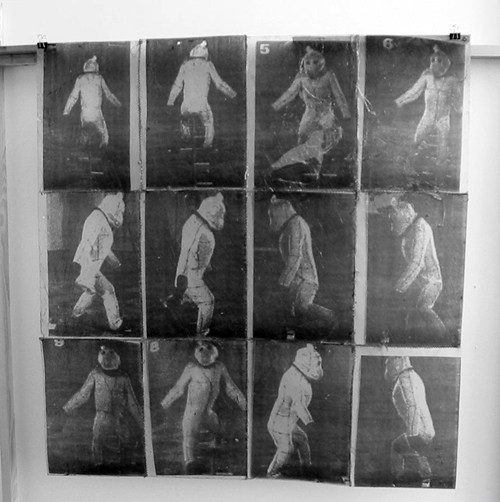

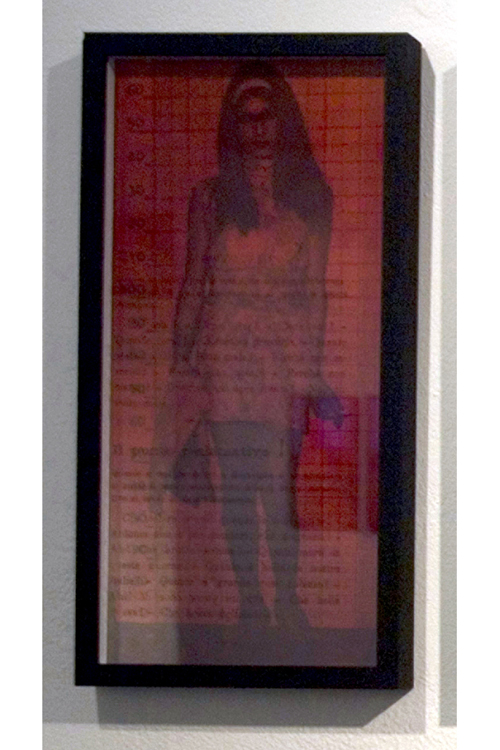

En effet l’infans, le sans-parole, ne peut pas dire de quelle fin il aimerait finir. Ces gamins sur lesquels on opère une chirurgie photographique (moi-même, n’ai-je pas été placé devant un gros appareil noir, dans une arrière-boutique qui sentait le moisi et l’Odradek, après avoir été déguisé en petit Bersagliere, avec sur la tête un drôle de chapeau dur et rond garni de plumes de coq?) me font inévitablement penser à ces animaux utilisés pour les expérimentions scientifiques, à ce Max, par exemple, chimpanzé mâle de neuf ans qui, revêtu d’une salopette marquée de points et de lignes, est poussé à marcher en ligne droite, vers la caméra et son flash automatique. Cela n’a – bien sûr – rien à voir avec le fascisme. Il s’agit là d’expérimentions scientifiques tout à fait légitimes et assez récentes pour échapper à toute analogie historique (le livre dont j’ai tiré ces extraits, Le centre de gravité du corps et sa trajectoire pendant la marche, est paru en 1992, par les soins du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique). La démarche du chimpanzé y est analysée en comparaison avec celles de l’homo sapiens adulte et de l’homo sapiens enfant.

Ce qui finalement nous attire dans ces expérimentations c’est – au delà de l’accoutrement du sujet, qui est masqué un peu comme un monument en temps de guerre ou comme un de nos Balilla – le fait qu’il soit aliéné de son individualité multiple pour en extraire les signes d’un seul de ses attributs – la démarche, dans ce cas-là. Ce qui fait qu’il ne nous est connu qu’en tant que signe réifié. De la même manière, nous épions et interprétons les gestes d’un être aimé, sa respiration même, comme des signes qui nous sont adressés, sans voir que cet être est en train de s’éloigner de nous et de notre propre fascisme, c’est-à-dire de la volonté de cooptation de l’autre dans notre système à nous.

T-04. Colpi proibiti

«Parce que, pour le fasciste, tout est dans l’Etat, et rien d’humain ou de spirituel n’existe, ni n’a de valeur, en dehors de l’Etat». Enciclopedia italiana, volume XIV (1932), article «Fascismo», chapitre «Dottrina», signé par Benito Mussolini mais rédigé par le philosophe Giovanni Gentile.

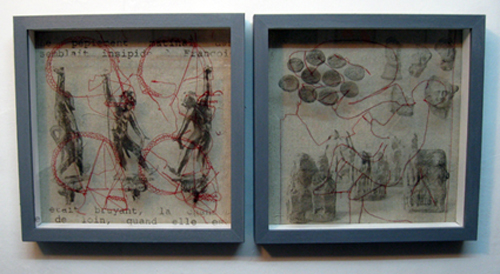

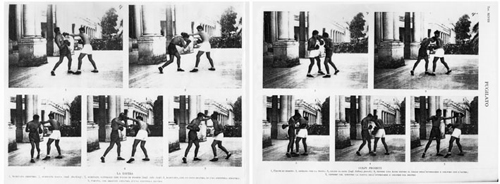

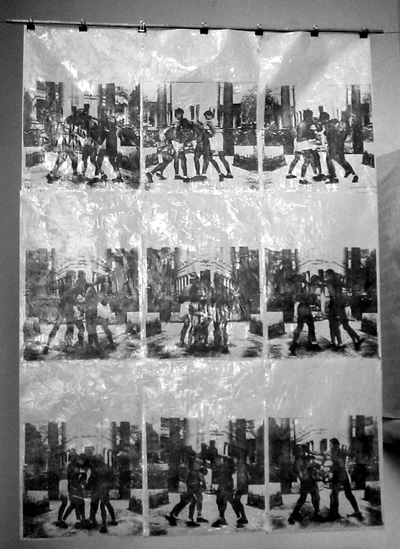

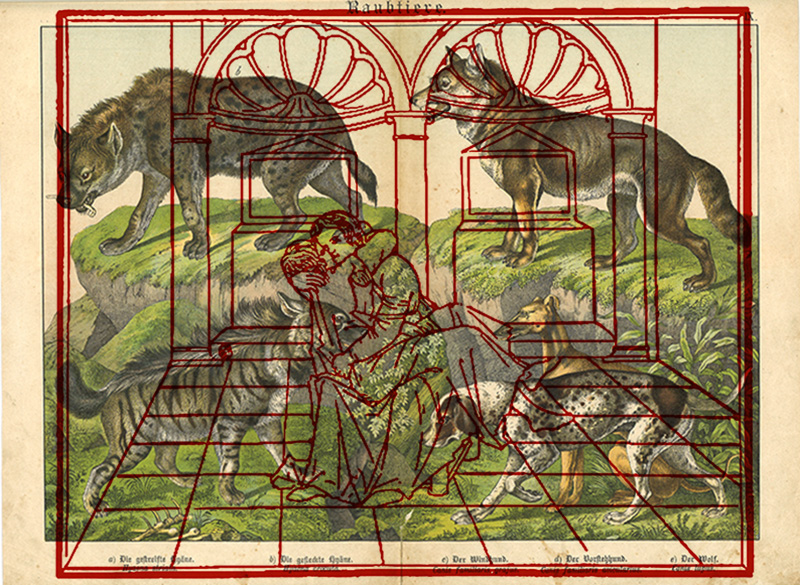

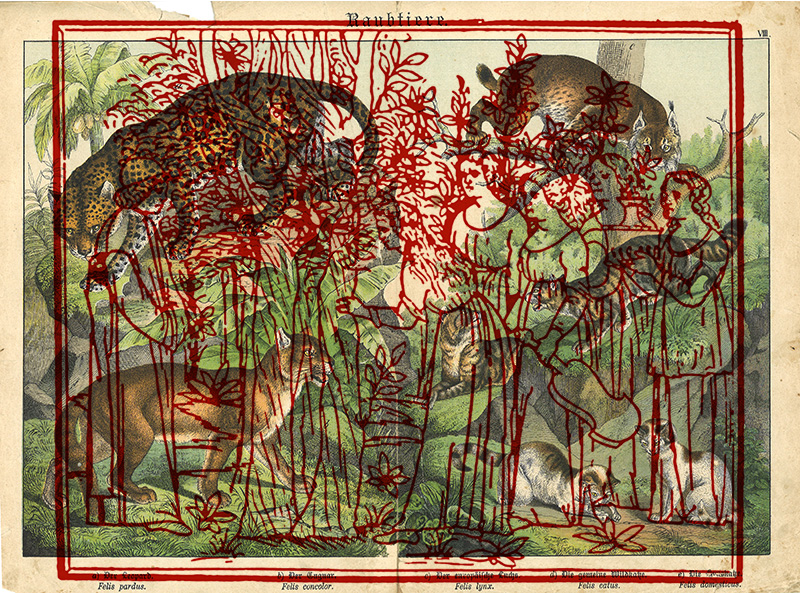

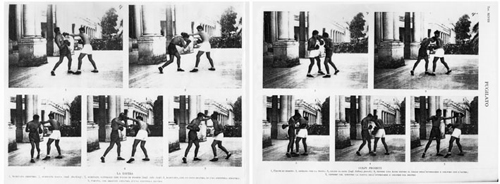

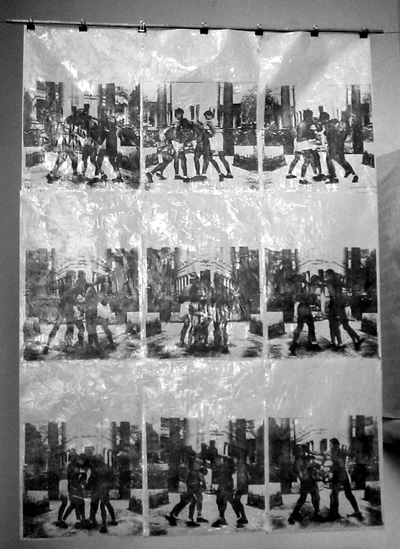

Mais qu’est-ce qu’il a à voir avec le fascisme et son esthétique, ce travail qui a pour titre Coups interdits? En fait, il n’est pas plus que la simple reproduction parodique de deux planches de l’Enciclopedia italiana, illustrant l’article «Pugilato» (boxe) et montrant les coups de défense, ainsi que ceux défendus (qui sont aussi répertoriés, ça va de soi, pour qu’on puisse les sanctionner). Je me suis ainsi amusé à superposer schivata indietro et colpo di gomito, parata col braccio sinistro et colpo al rene (ingl. kidney punch), bloccata col guanto destro et entrata con la testa.

A regarder avec un minimum d’attention ces images, on voit comment les deux braves boxeurs ont été placés sur le fond d’un bâtiment d’inspiration classiciste. Il s’agit sans doute de l’Accademia fascista di Educazione fisica, édifiée entre 1926 et 1932 d’après les dessins du très officiel architecte Del Debbio, et qui était bien achevée au moment de la parution de l’article dans le volume XXVIII (publié en 1935) de l’Enciclopedia.

En fait, comme l’article de l’encyclopédie nous le rappelle, les boxeurs, amateurs ou professionnels, étaient encadrés dans la Federazione Pugilistica Italiana, qui faisait partie du CONI (Comitato Olimpico Nazionale Italiano), qui était à son tour dépendant du PNF (Partito Nazionale Fascista). Seule l’Allemagne avait une pareille organisation, alors que «dans les autres nations européennes, les fédérations étaient des organismes sociaux sans aucun investissement de la part des pouvoirs constitués».

Le contexte de ces images, ainsi que les informations qui nous sont fournies par le rédacteur de l’encyclopédie, nous disent que nous nous trouvons devant des boxeurs fascistes. Or ma question est: un boxeur peut-il être fasciste? Ou, à le dire autrement, peut-on avoir une boxe fasciste et une boxe non fasciste? Et une boxe démocratique, à quoi ressemblerait-elle? Comme moi, vous n’avez pas de réponse à cette question. Parce qu’on peut être boxeur et démocratique, mais pas boxeur démocratique.

De la même manière on peut se demander: un enfant peut-il être fasciste? Et un artiste?

Toutes les particularités que je viens de mentionner à propos de l’esthétique fasciste (a-contextualité, a-temporalité, cooptation, dépendance) ne me sont pas inconnues. Et ma propre pratique artistique n’est pas exempte de tous ces procédés qui relèvent du kitsch (décontextualisation, changement d’échelle, reproduction ad libitum, ressassement dans la multiplication de l’image).

C’est quoi, enfin, qui explique ma propre fascination pour ces sujets (l’esthétique du Mal accompagnée des nomenclatures, classifications, énumérations incantatoires, et expérimentations scientifiques dont le sujet est l’homme, toutes ces anthropologies et ces anthropométries qui ressemblent assurément à un théâtre du sadisme)? Quelle est ma propre relation à ces Balilla pris en photo, à ces boxeurs dans le vide et à ces bâtisseurs du néant?

Texte de juin 2003. Pour les images de la conférence de décembre 2015

à l’EAD de Strasbourg, je vous renvoie au diaporama :

Quatre thèses sur l’esthétique du fascisme.

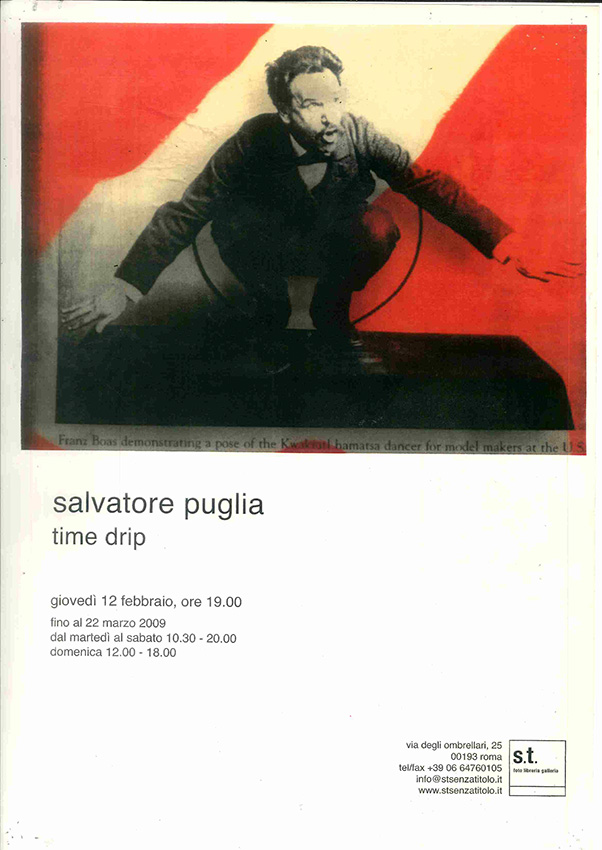

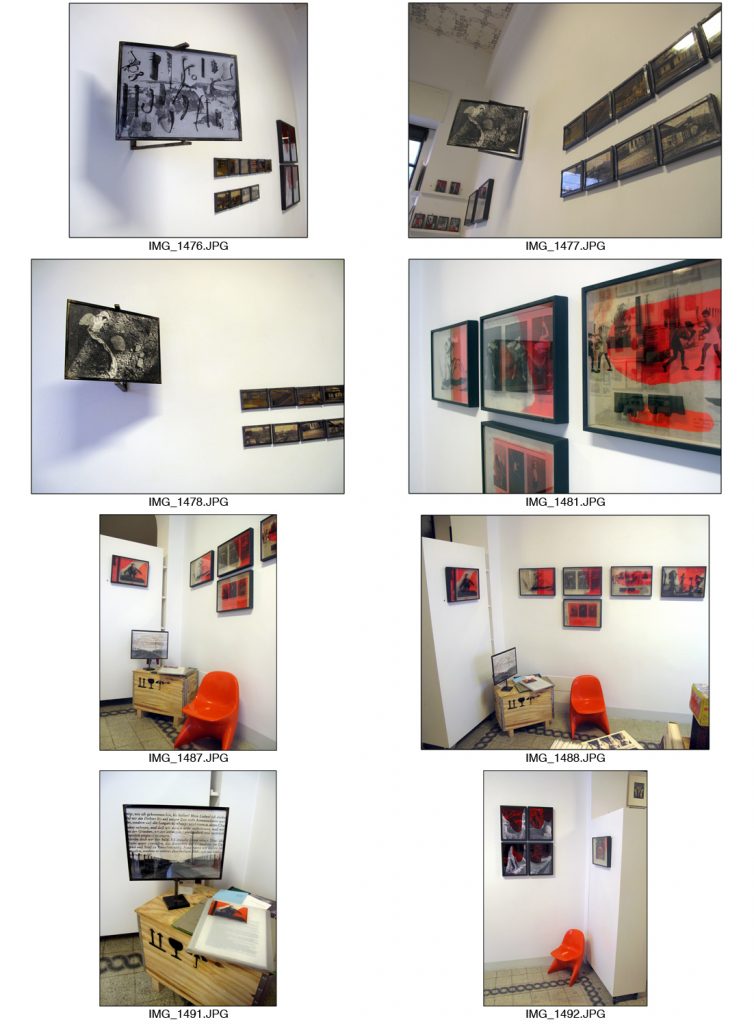

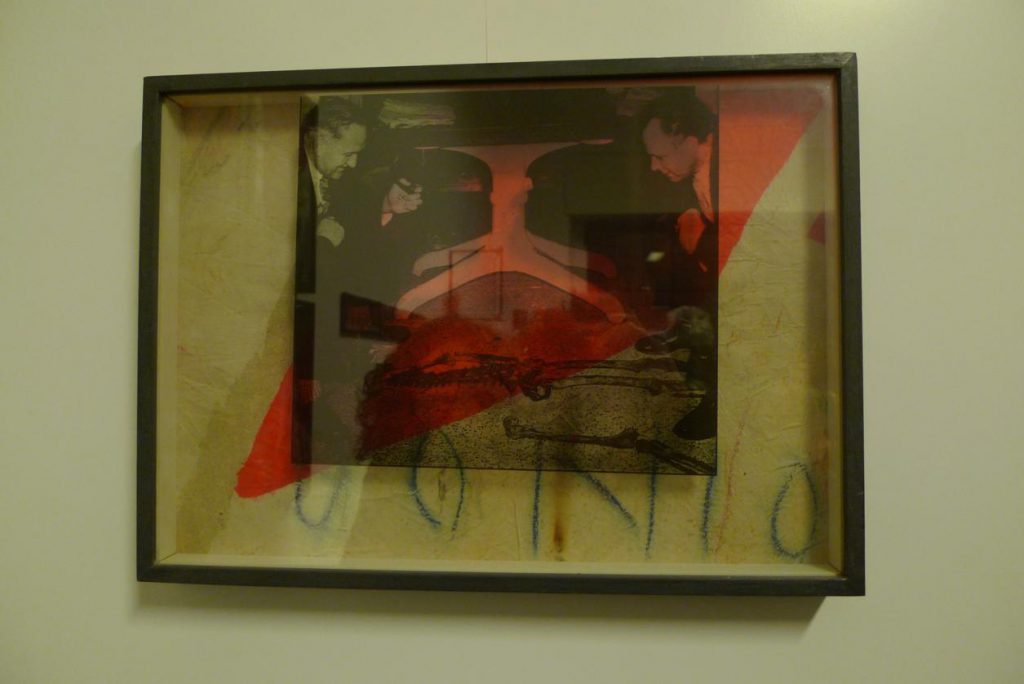

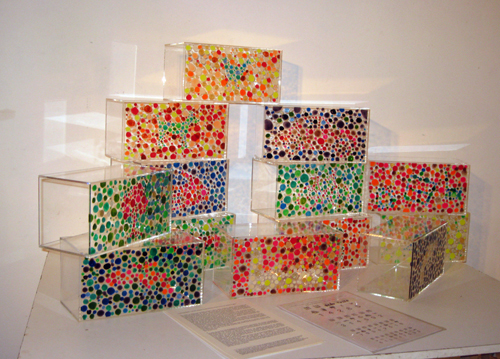

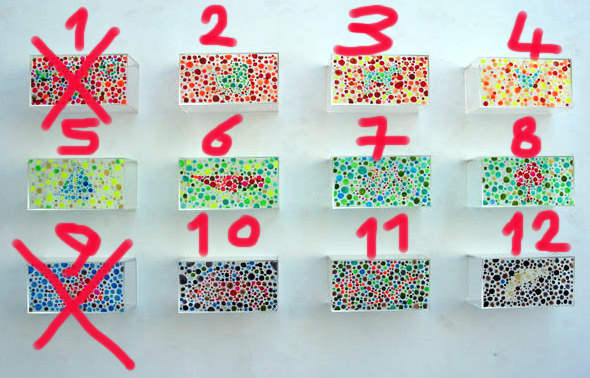

Time drip, s.t. gallery.

Time drip, s.t. gallery.