Construction of a parachute

I

Assembly manual

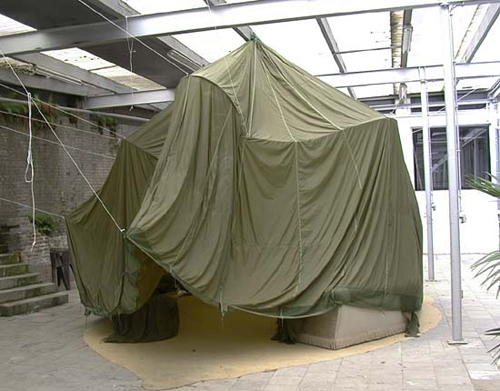

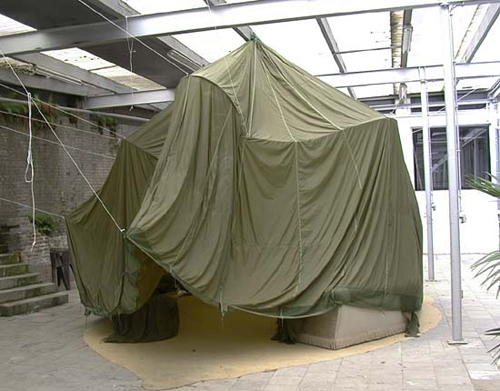

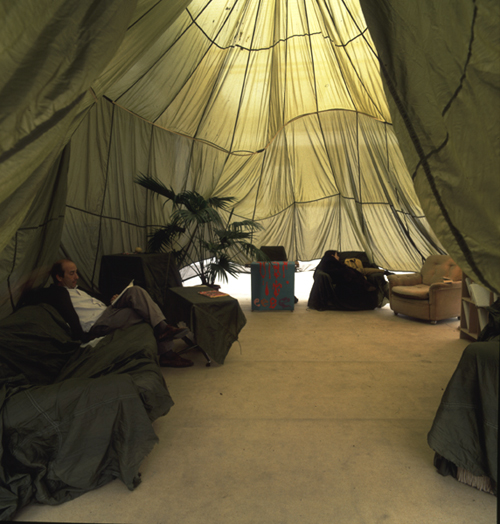

Take a second hand parachute, either green or white, measuring eleven meters in diameter. Hang it between trees in a park or between walls in a courtyard or even in a public square. Apply rings to the junctions of the fabric and stretch nylon threads between such rings and the surrounding branches or walls. It will be displayed in such a way as to recall the umbrella shape of a falling parachute.

Suspend this structure at the height of half a meter from the ground. Lift up a point at its extremity to sketch the lines of an entrance.

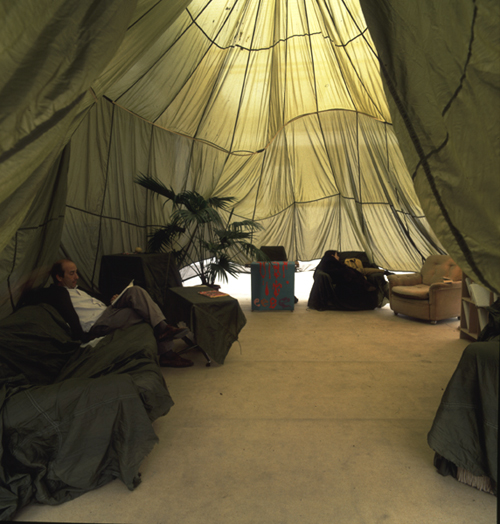

Find two couches, three arm-chairs, a small table, a chair, a fridge. Cover them with the off-cuts of the emergency parachute.

Place a potted palm tree between the fridge and the table. Place a bookshelf between a couch and an arm-chair, and a reading lamp beside the bookshelf.

All this furniture should be set in a circle over a large oriental carpet, leaving empty the central space. Do not be afraid of creating a luxurious, calm, voluptuous place.

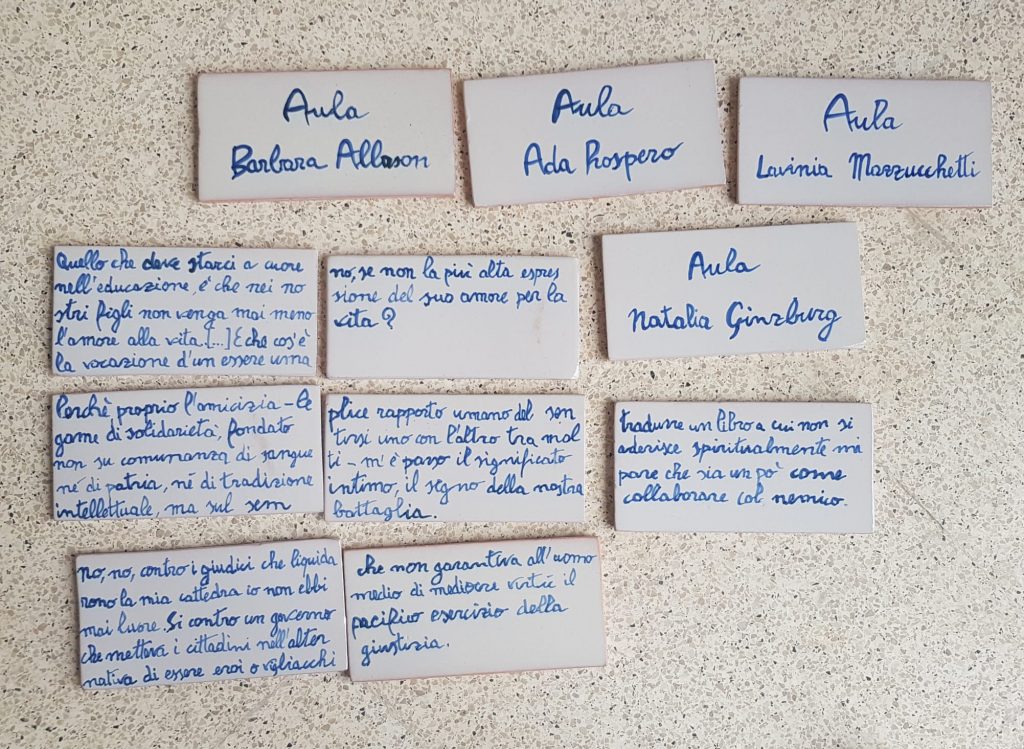

Choose twelve or fifteen books, following your own taste and opinions; they will constitute an ideal and universal library. Cover each with an identical white paper, identify it with a Latin number.

Pick up the best white wines from Italy, France, and Spain, fill the fridge with them, and with every kind of beverage that can satisfy any particular liking.

Hire for the duration of the event an experienced hostess, dress her (or him) with an uniform sewn with the remains of the emergency parachute.

Instruct the host(ess) not only to invite and welcome all the passers by, but furthermore to fulfill –within the limit of the possible and the decent- their desires.

Finally, take care that the interior of the dome is sufficiently ventilated and of a pleasant temperature.

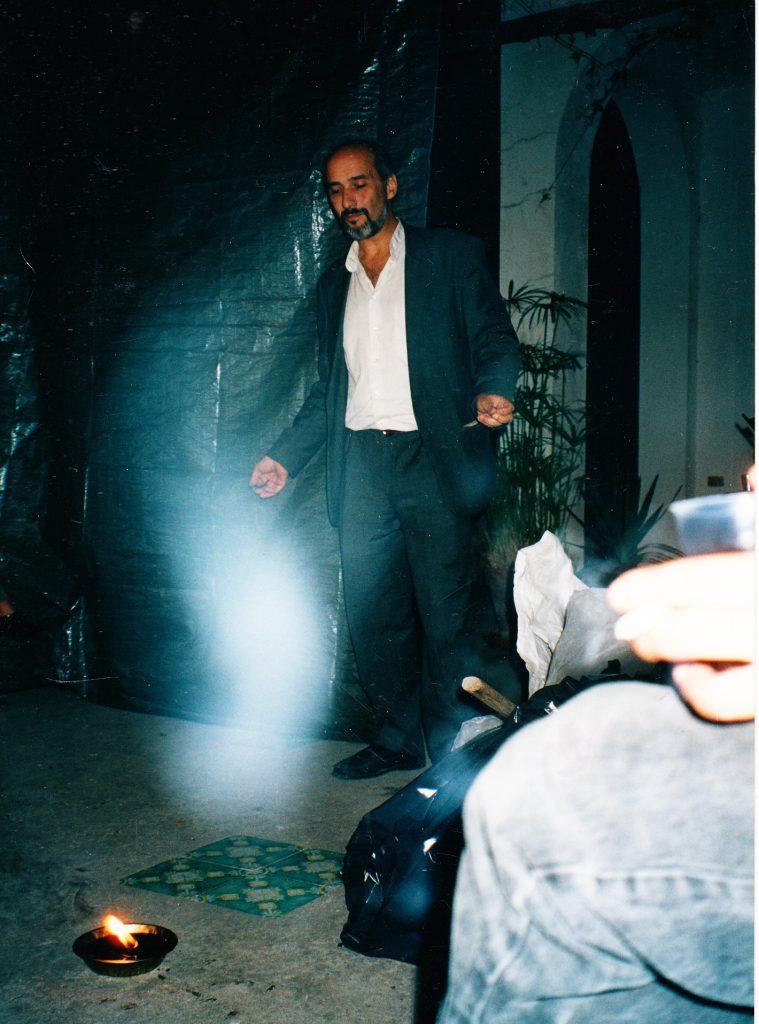

Rules: a host will constantly be present in the space. He will not impose any speech nor will he ask the guests who they are or who has sent them. However, he should always be ready for the possibility of conversation, which will probably be encouraged by the comfortable standing of the environment. The circular disposition of couches and chairs is likely to create a verbal exchange between conversation and chatter, confidence and speech, in a floating mood between private expression and public extension.

Some performances, readings, unplugged concerts will be executed following a program posted every morning. Other events will be improvised according to the encounters and exchanges that will occur day by day.

Note: as a parachute is mobile by definition, it will not remain in the same place in excess of three days.

II

User’s instructions

1.

Our parachute is a demonstrative space. It is a manifesto for the free circulation of individuals.

What is a parachute, if not a tool meant to slow down a fall?

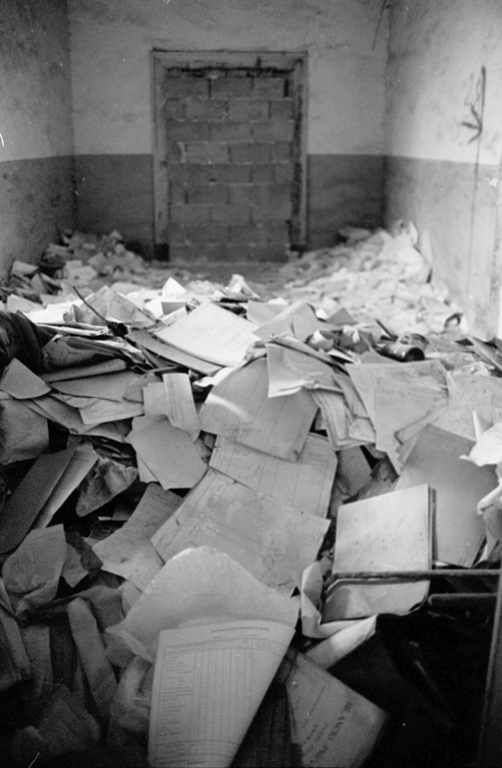

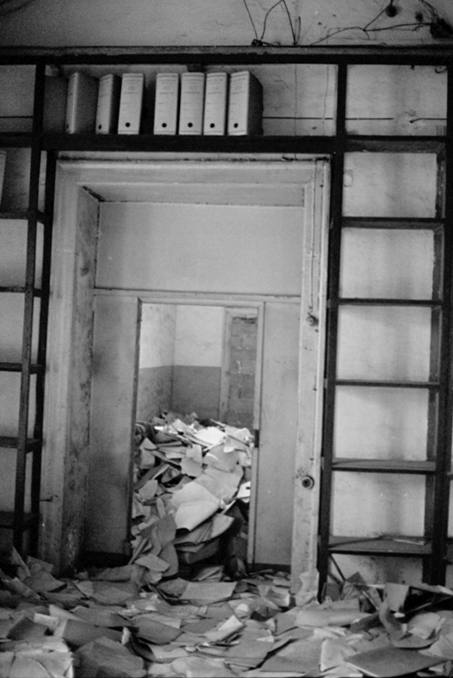

If such a tool is being put to use, it is because there is a fall; there is a threat to life, there is emergency.

A parachute is not a tent, is not anchored to the ground; it floats in a space between sky and earth–even the precise spot of its landing is uncertain. Once on land, it no longer has a further function. Its quality is lightness and lightness is not required whilst one has his feet on the ground.

2.

To find oneself under a parachute is not a matter of hospitality; it is a matter of shelter.

If a tent is the symbolic space for hospitality, a parachute is the symbolic space of refuge and sheltering.

To offer somebody shelter is not the same as to offer hospitality. Hospitality is something that is exchanged in a community of peers, is a matter of politeness. In our time, sheltering has nothing to do with politeness. Today the only situations where hospitality and refuge coincide are those of an environmental danger: only Bedouins or Inuit can greet the stranger as Alcinous in the island of Scheria or Lot in the outskirts of the town of Sodom.

An effective welcoming in the Western world is to give shelter: it implies that the giver is in a position of power, and the receiver is in a state of weakness. The power that is exercised there does not answer to the codified rules of genteel behaviour. The fact is that recognition, which is the dialectical condition of hospitality, does not play such a basic role in the decision of giving shelter.

3.

But the evidence of the need is already a recognisable form; such a basic recognition is what makes an unquestioning and unconditioned asylum almost impossible.

This is why not to ask “who are you?” is but an exercise: such a question can be unexpressed but it remains implicit in the acknowledgement of a request. There is no situation of request which does not introduce itself with a sign: such a sign says where the one who is knocking at the door comes from, from whom he is sent, which danger he represents.

The call to give shelter implies a call from a point of danger; the guest is in danger and he carries this danger with him to the house of the host. Who really feels like opening his arms to the danger and the unknown? Only somebody who already lives as precarious a condition as the one who has and can; somebody who already takes his own life as an excess and indeed confounds what is necessary and what is superfluous.

The parachute exists to measure our ability to receive: we propose the exercise of turning generosity toward immoderation and transfiguring etiquette into unmotivated and uninterested pomp. Anybody who presents himself at the threshold of the parachute will be given not only a favourable reception (in another idiom, we might refer to the anti-psychiatric effort “to bracket the disease”) but will also be offered the best of our belongings. The reception will be transformed into a luxurious hospitality lacking any purpose except the pleasure and the difficulty of sharing another’s presence, good wines, good books and conversation.

4.

The host is the recipient. He is the dweller and the owner of a space which is forcefully delimited. Such spatial delimitation can be effective in the same way as the door of a house; or symbolically, as a curtain or the steps of a church.

One cannot –normally- offer to others what is not his own. There is no protection without the exercise of a sovereignty: To receive indeed means to make public, for the time and in the space of the opening, an exclusive and private place.

The guest is made inside: a new, larger space of conviviality is created. Such transformation of the private into the shared is made on the threshold; it is there where the owner invites, gives way or decides to resist the intrusion.

One cannot open what is not his own; he can, though, open up a door that would already be ajar. This is why the welcoming of the stranger would be easier to a dweller who would be partly a stranger, partly an intruder.

This half stranger would be a kind of guarantor, somebody who would answer for the other, the newly arrived–even if he does not know him.

5.

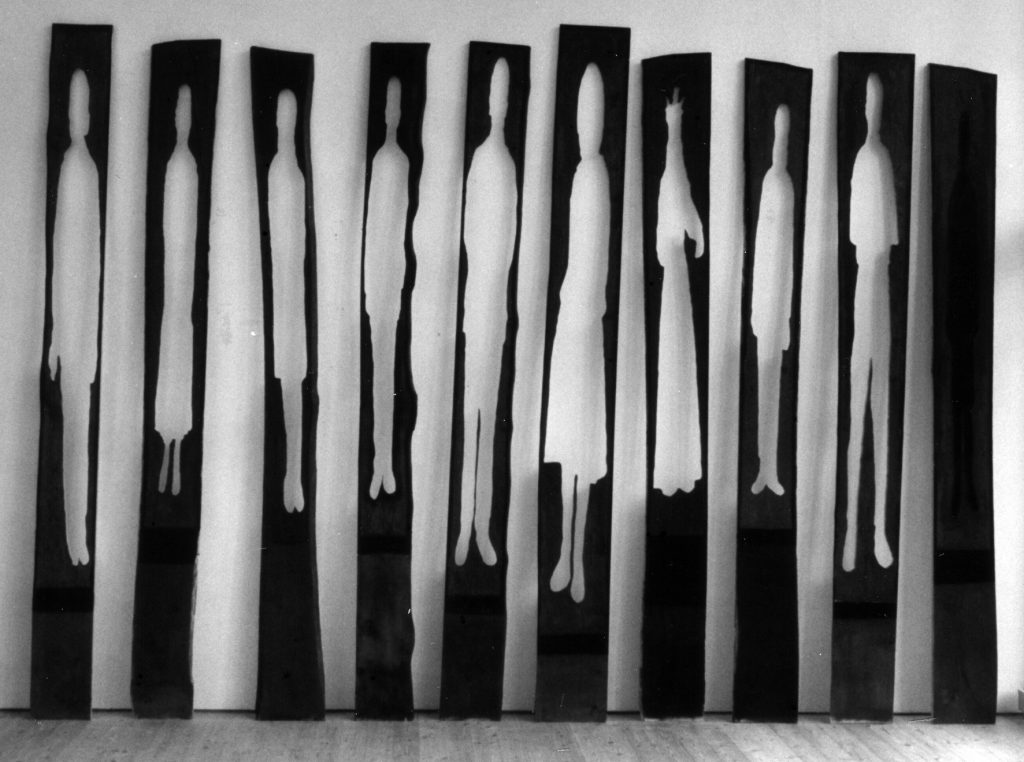

Imagine an open parachute, suspended at a few feet from the ground, accessible from every side and impossible to close: it would be the emblem of an invitation without identification and without judgement, a space where what is proper and what is common would be confused.

Such indeterminacy would be possible only if the host would not master a real power but would be himself an abusive occupier: his place would be precarious and could effectively protect nobody. But it would protect symbolically: it would be something similar to antiquity’s Asylum (from the Greek a-sylon: out of violence) or the children’s games where one cannot be touched as long as he stays in a magic circle. That would be a matter of fact, neither within nor outside the law.

An absolute and unconditioned hosting could be based only on a misunderstanding or on a re-appropriation: the host should not own any space and, being himself a temporary guest, would place himself in a chain of invitation. Not being asked “who are you?” he would not have to ask “who sent you?” Only in such a way–by dispossessing himself of any power that would not be occasionally borrowed—could one be host and guest at the same time, recipient and contained, not really powerful nor absolutely weak. Only in such a way could one, at the same time, be responsible in two directions: toward the sovereigns–-the authority–and the visitors-–the intruders.

And only an abusive guest introduced by a less abusive one can take the invitation without being doomed to show a sign that would certify his legitimacy, which is his coming from somewhere. Not being identified, he could not represent any danger.

Only an anonymous and abusive guest-–that is to say: a parasite–can play on the same level with the host in the social game: he would have nothing to ask, but he would take the risk of being kicked out of the mansion. But then a violence against him would be a violence against every other guest. Since, following the medieval principle quoted by Hannah Arendt in The Origins of Totalitarianism, “Quid est in territorio est de territorio”, the justification of his presence would be the mere fact of his presence.

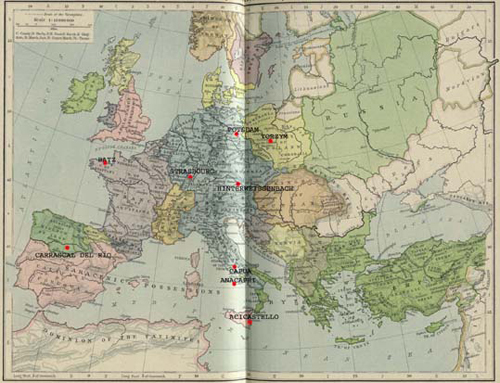

Note: a first Parachute was experimented in Maastricht in May 2000, in the protective environment of the backyard of the Jan Van Eyck Academie.

Note: while I was writing this text (August 2000) I knew that an association Foreigner for foreigners had just been constituted in Rome, with the purpose of “examining the irregularities practised by the institutions of the Italian State against strangers”.

Note: The tents that have been raised in the last years by the “sans papiers” under the aisles of the churches were neither metaphorical nor allegorical. I am thinking about those in the church of Saint Ambroise, whose doors were pulled down with axes by the French police in August 1996; or to the beautiful white tents still standing (November 2000) inside the church of the Béguinage in Brussels.

Evidently, whoever finds himself in the extreme situation of seeking shelter in a sacred space appeals less to the protection of a divinity that perhaps he doesn’t recognize than to the residues of an ecclesiastic right that is no longer accepted by national legislations, and to the fact that the breaking-in of public officers in such places is still perceived by public opinion like a sort of sacrilege.

Appendix: a short list of recent books on the issues of hospitality and refuge

J. Derrida, „Le mot d’accueil“, in Adieu à Emmanuel Lévinas, Paris 1997.

J. Derrida, De l’hospitalité, Paris 1997.

J. Derrida, Cosmopolites de tous les pays, encore un effort!, Paris 1997.

K. Heilbronner, Immigration and asylum law and policy of the European Union, The Hague London Boston 2000

E. Jabès, Le livre de l’hospitalité, Paris 1991.

D. Joly, Haven or hell? Asylum policies and refugees in Europe, Warwick 1996

E. Lévinas, „Les villes-refuges“, in L’Au-delà du verset, Paris 1982.

F. Nicholson, Refugee rights and realities: evolving international concepts and regimes, Cambridge UK 1999

C. Pohl, Making room: recovering hospitality as a Christian tradition, Grand Rapids-Cambridge 1999.

S. Reece, The stranger’s welcome: oral theory and the aesthetics of the Homeric hospitality scene, Ann Arbor 1993.

R. Scherer, Zeus hospitalier: éloge de l’hospitalité. Essai philosophique, Paris 1993.

P. Ségur, J.L. Gazzaniga, La crise du droit d’asile, Paris 1998