Ogni volta che ho cercato me stesso, ho trovato gli altri.

Ogni volta che ho cercato me stesso, ho trovato gli altri.

Ogni volta che li ho cercati, in loro non ho trovato

che me stesso straniero.

Che io sia il singolo-moltitudine?

Da: Mahmud Darwish, Murale, Milano 2005, traduzione dall’arabo di Fawzi al-Delmi.

.

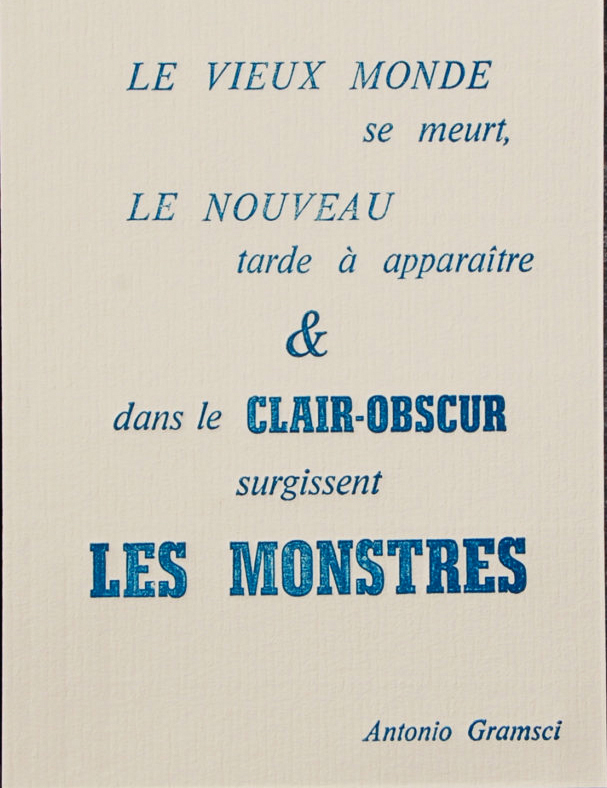

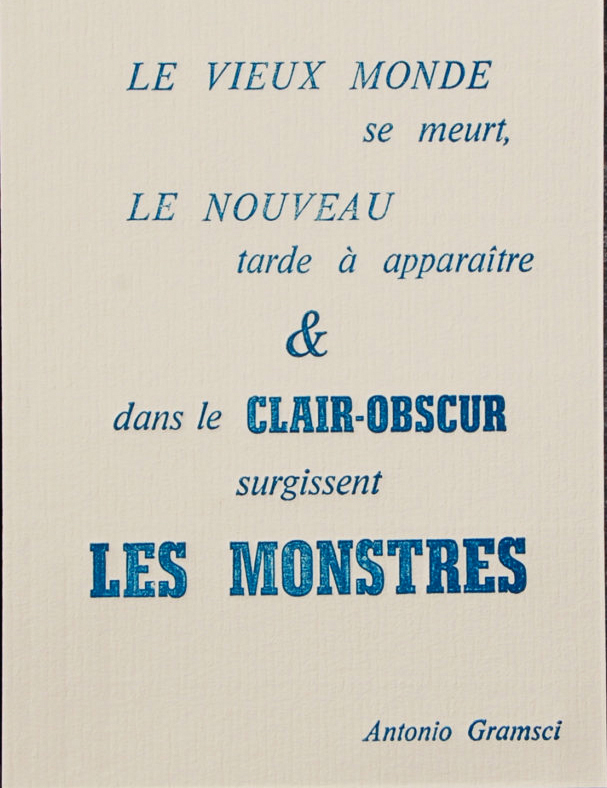

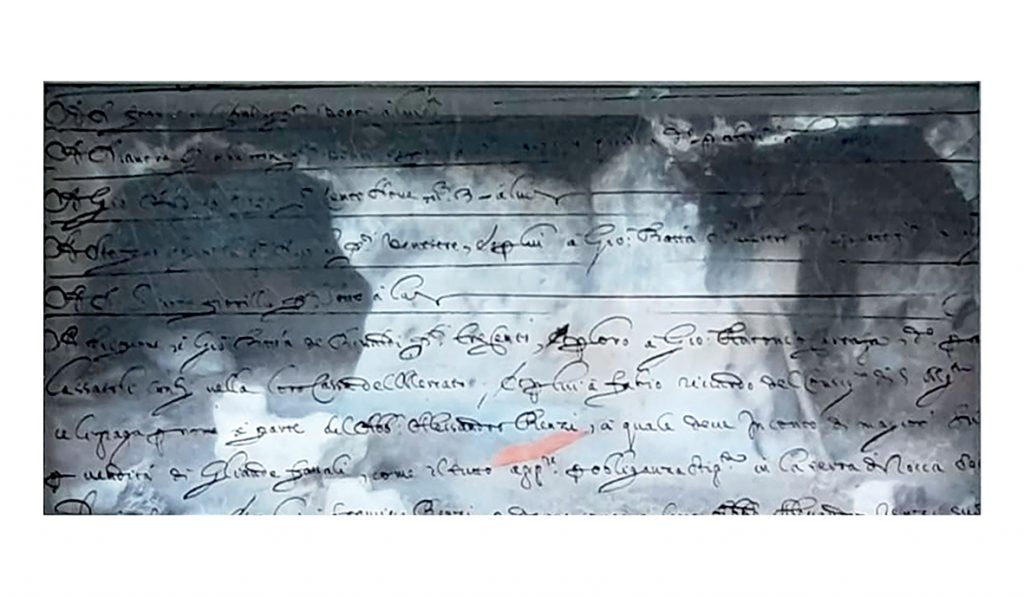

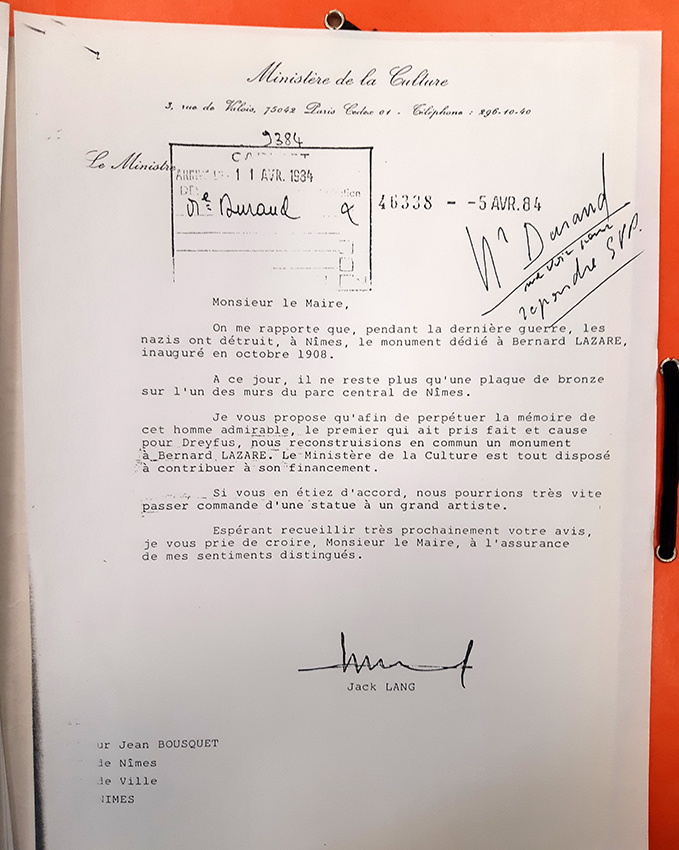

La frase di Gramsci, scritta nel carcere di Turi nel 1930 (fra il crack di Wall Street dell’ottobre del ’29 e l’affermazione del nazismo e dello stalinismo), ‘’La crisi consiste appunto nel fatto che il vecchio muore e il nuovo non può nascere: in questo interregno si verificano i fenomeni morbosi più svariati’’ diviene “Il vecchio mondo sta morendo. Quello nuovo tarda a comparire. E in questo chiaroscuro nascono i mostri”, sui manifesti verdi e rossi comparsi per le vie di Roma nel dicembre 2018.

Il cambiamento lessicale è stato operato dall’artista cileno Alfredo Jaar, il quale, per una sua installazione sui pannelli di affissione pubblica del Comune di Roma, ha utilizzato una traduzione italiana della traduzione francese di Gramsci, la quale recita: ‘’Le vieux monde se meurt, le nouveau monde tarde à apparaître et dans ce clair-obscur surgissent les monstres’’ (vedi la sua intervista a Artribune :

https://www.artribune.com/arti-visive/street-urban-art/2018/12/cosa-significano-quei-manifesti-su-gramsci-che-hanno-invaso-roma/).

”La dichiarazione che ho usato per il mio intervento pubblico a Roma è una riflessione perfetta su quello che penso stia accadendo oggi in Italia”, dichiara ad Artribune l’artista Alfredo Jaar. “La frase originale di Gramsci era la seguente: La crisi consiste appunto nel fatto che il vecchio muore e il nuovo non può nascere: in questo interregno si verificano i fenomeni morbosi più svariati. Questa dichiarazione è stata tradotta in molte lingue e la mia versione preferita era in francese: Le vieux monde se meurt, le nouveau monde tarde à apparaître et dans ce clair-obscur surgissent les monstres. Poi per caso, ho scoperto una versione italiana, traduzione di quella francese, che mi è piaciuta moltissimo perché al posto della parola interregno usa chiaroscuro, e al posto di i fenomeni morbosi più svariati usa mostri. Ho usato questa traduzione perché la trovo potente e poetica allo stesso tempo”. E così l’artista cileno ha realizzato manifesti verdi e rossi con caratteri in bianco che recitano: Il vecchio mondo sta morendo. Quello nuovo tarda a comparire. E in questo chiaroscuro nascono i mostri, una citazione della prima metà del Novecento, ma purtroppo sempre attuale. “A certi studiosi di Gramsci potrebbe non piacere, ma come artista mi sono preso la licenza poetica di usarla” afferma Jaar. “In un certo senso, si è trattato di un pretesto per portare la voce e le idee di Gramsci nell’Italia di oggi, perché sento che è necessario più che mai.” (…)

Questa stessa traduzione francese che ha ispirato la versione di Jaar era stata ripresa da Edwy Plenel nel suo Dire non (Don Quichotte éditions, Paris 2014, pp. 17-18). Plenel è ben consapevole di avere scelto una versione poetica, che non tradisce però il senso originario della citazione gramsciana: ‘’Il est des alarmes que leur pertinence transforme en sentences proverbiales, bien loin de leur contexte historique. Au risque, parfois, d’une perte d’intensité, où s’affadit l’inquiétude première. Ainsi de cette réflexion d’Antonio Gramsci dans ses Cahiers de prison sur la crise comme conflit entre un vieux monde en train de mourir et un nouveau monde pas encore né. ‘’La crise consiste justement dans le fait que l’ancien meurt et que le nouveau ne peut pas naître’’, écrit précisément, en 1930, le communiste italien, emprisonné par le fascisme jusqu’à sa mort en 1937. Or on occulte trop souvent la phrase qui suit, où gît l’essentiel : « Pendant cet interrègne, on observe les phénomènes morbides les plus variés ». Essentiel sur lequel, en revanche, insiste, non sans bonheur, une variante poétique, souvent citée bien que littéralement infidèle au texte original italien : « Le vieux monde se meurt, le nouveau tarde à apparaître et, dans ce clair-obscur, surgissent les monstres ».

Questa stessa traduzione francese che ha ispirato la versione di Jaar era stata ripresa da Edwy Plenel nel suo Dire non (Don Quichotte éditions, Paris 2014, pp. 17-18). Plenel è ben consapevole di avere scelto una versione poetica, che non tradisce però il senso originario della citazione gramsciana: ‘’Il est des alarmes que leur pertinence transforme en sentences proverbiales, bien loin de leur contexte historique. Au risque, parfois, d’une perte d’intensité, où s’affadit l’inquiétude première. Ainsi de cette réflexion d’Antonio Gramsci dans ses Cahiers de prison sur la crise comme conflit entre un vieux monde en train de mourir et un nouveau monde pas encore né. ‘’La crise consiste justement dans le fait que l’ancien meurt et que le nouveau ne peut pas naître’’, écrit précisément, en 1930, le communiste italien, emprisonné par le fascisme jusqu’à sa mort en 1937. Or on occulte trop souvent la phrase qui suit, où gît l’essentiel : « Pendant cet interrègne, on observe les phénomènes morbides les plus variés ». Essentiel sur lequel, en revanche, insiste, non sans bonheur, une variante poétique, souvent citée bien que littéralement infidèle au texte original italien : « Le vieux monde se meurt, le nouveau tarde à apparaître et, dans ce clair-obscur, surgissent les monstres ».

Nous vivons ce surgissement des monstres, ces phénomènes morbides des temps de transition et d’incertitude qu’à tort, l’on s’est habitué à nommer crises, comme s’il s’agissait de fatalités, alors qu’ils mettent à l’épreuve notre capacité à échapper aux pesanteurs du présent et à réinventer les espérances du futur. Ils sont bien là, ces monstres, devant nous, défilant dans nos rues, envahissant nos médias, imposant leurs imaginaires de violence et de haine (…)’’

Vedi, per la dizione originaria italiana, il rimarchevole lavoro di trascrizione e messa a disposizione del pubblico intrapreso da Alberto Soave in

Passato e presente

Qui la citazione, ripresa dal sito di Soave, ricollocata nel suo contesto:

‘’L’aspetto della crisi moderna che viene lamentato come «ondata di materialismo» è collegato con ciò che si chiama «crisi di autorità». Se la classe dominante ha perduto il consenso, cioè non è più «dirigente», ma unicamente «dominante», detentrice della pura forza coercitiva, ciò appunto significa che le grandi masse si sono staccate dalle ideologie tradizionali, non credono più a ciò in cui prima credevano ecc. La crisi consiste appunto nel fatto che il vecchio muore e il nuovo non può nascere: in questo interregno si verificano i fenomeni morbosi più svariati.’’

(Quaderno 3 (XX), § 24. Antonio Gramsci, Quaderni del carcere. A cura di Valentino Gerratana. Torino, Einaudi, 1975, volume I, p. 311. Ringrazio Eugenio Testa, compagno di strade romane, di manifestazioni e di frequentazioni dell’Istituto Gramsci di Paolo Spriano negli anni Settanta.)

‘’Morboso’’, in italiano, è, mi pare, semanticamente assai vicino al concetto di mostruosità, nel senso di un fenomeno patologico, o anormale, forse più esplicitamente che il ‘’morbide’’ francese. Con ‘’morbo’’ in italiano si designa volentieri una malattia infettiva o degenerativa.

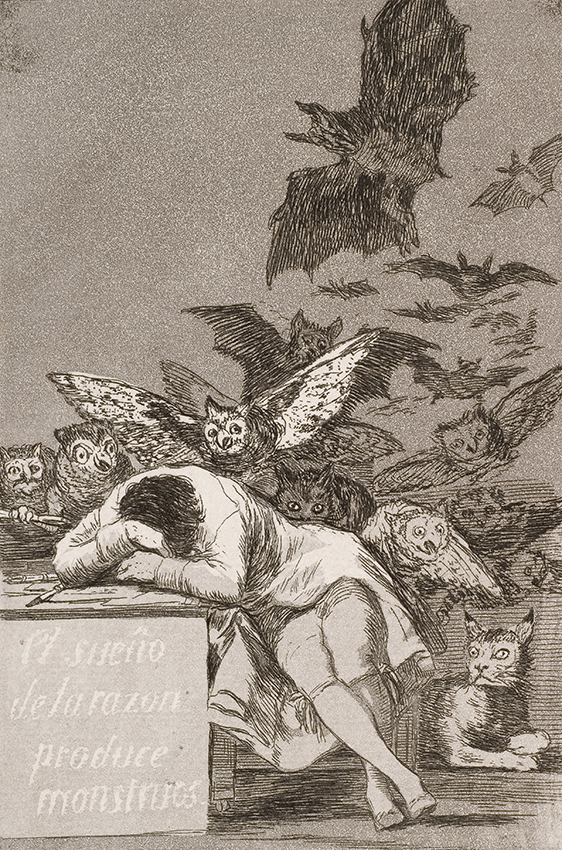

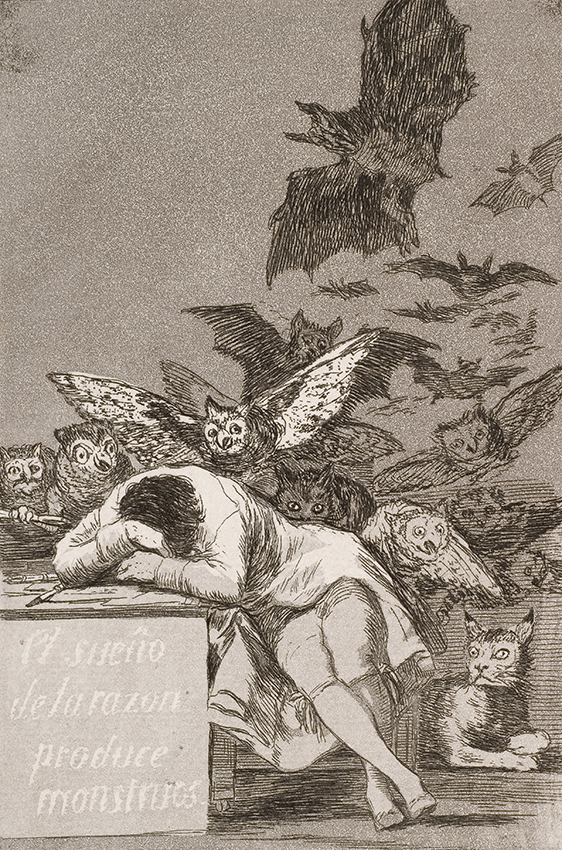

Comunque sia, è evidente che tanto il tuttora anonimo traduttore francese, quanto l’artista Jaar e il pubblicista Plenel abbiano fatto riecheggiare nei mostri di Gramsci quelli del pittore Goya: ‘’il sonno della ragione genera mostri’’, ‘’El sueño de la razón produce monstruos’’, acquaforte del 1797 della serie Los caprichos, per la quale Francisco avrebbe lasciato questo commento: ‘’La fantasía abandonada de la razón produce monstruos imposibles: unida con ella es madre de las artes y origen de las maravillas’’, in una sorta di autocritica artistica o, come altri vedono, di apologia dell’Illuminismo. ‘’I fenomeni morbosi più svariati’’, per Goya, non implicano necessariamente un’alienità dei mostri da noi.

Già nella ripresa di Plenel (inizio 2014) i ‘’mostri’’ cui si fa riferimento sono quelli dell’estrema destra risorgente, con il suo corollario di odio e intollerenza nei confronti de ‘’l’altro’’. Jaar ha gli stessi riferimenti per l’Italia del 2018, così come molteplici citazioni inglesi dell’espressione gramsciana avevano accompagnato l’elezione di Trump nel dicembre 2016 (“The old world is dying, and the new world struggles to be born: now is the time of monsters”). Sempre però il mostro è alieno, anche se originario dello stesso corpo sociale. Cioè: ‘’noi’’ siamo normali e ‘’quelli’’ sono strani, o stranieri.

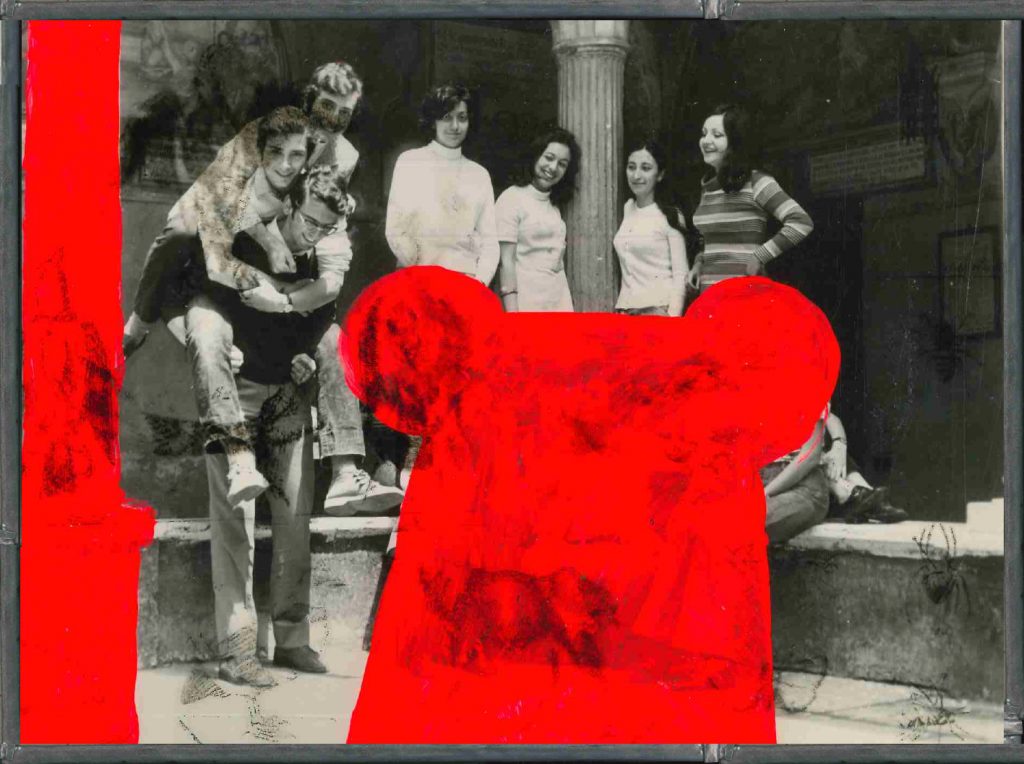

La difficoltà per me è già quella di dire ‘’noi’’, anche se, pur non volendolo, dentro a un ‘’noi’’ sono incluso: perché altrimenti, se sento ‘’quello è mussulmano’’ o ‘’quello è israeliano’’ o ‘’quello vota Le Pen’’, il mio primo moto non è di andare ad abbracciare la sua alterità, ma ho bisogno di un attimo di riflessione prima di includerlo nel mio panorama mentale e affettivo? (il mio ”noi”, eventualmente sarebbe quello di uno studente del Liceo classico statale Virgilio di Roma, figlio di repubblichini, che nell’anno 1972 era allo stesso tempo cattolico e comunista extraparlamentare; non mi pare che ce ne fossero due).

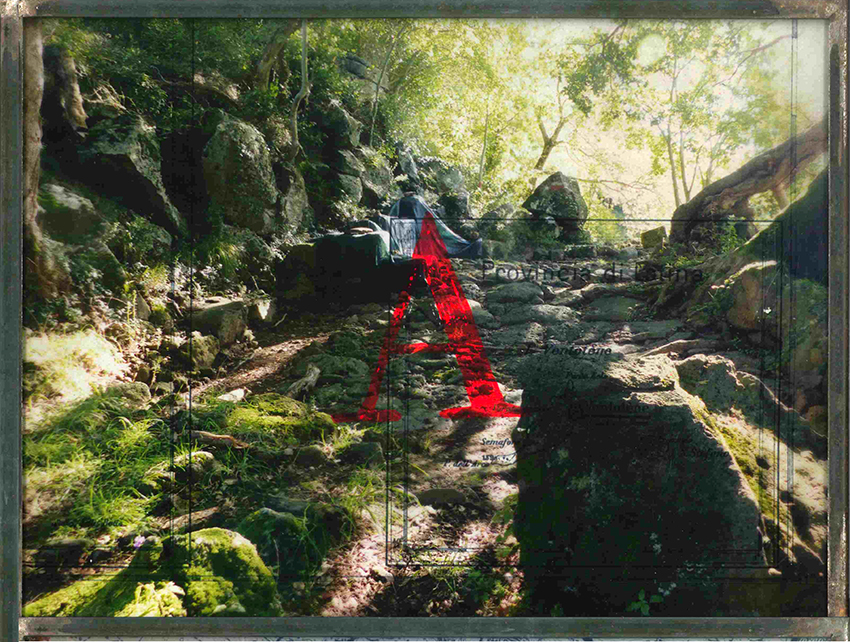

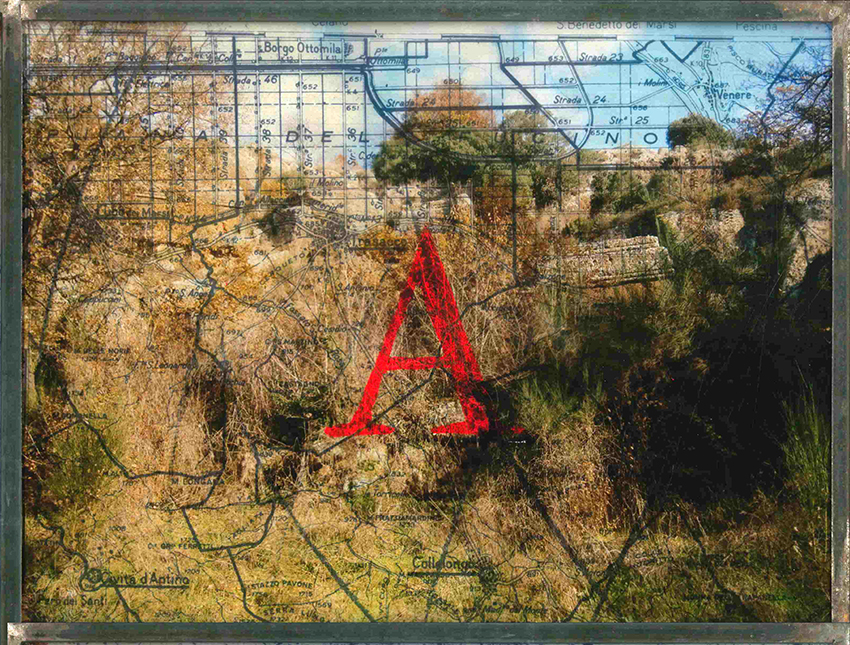

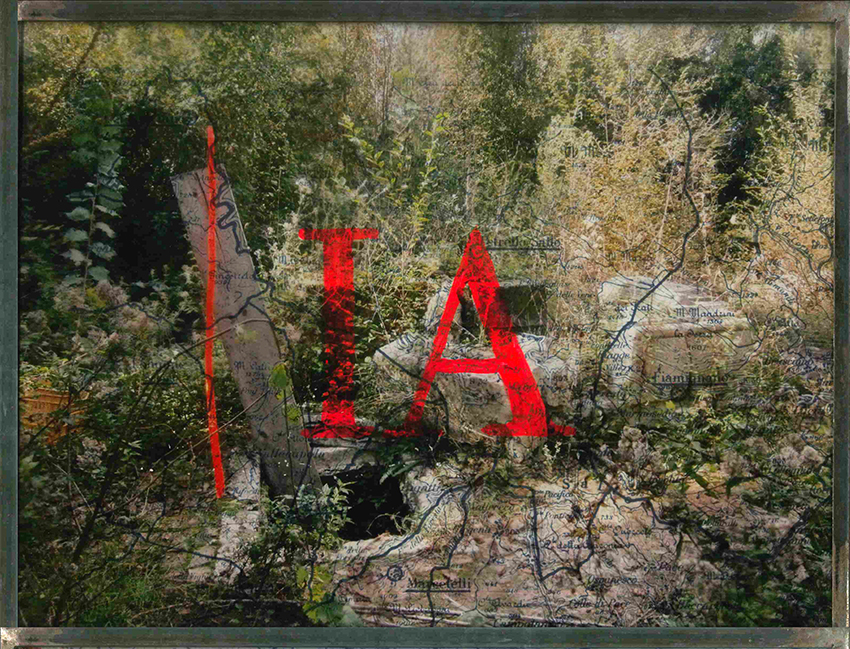

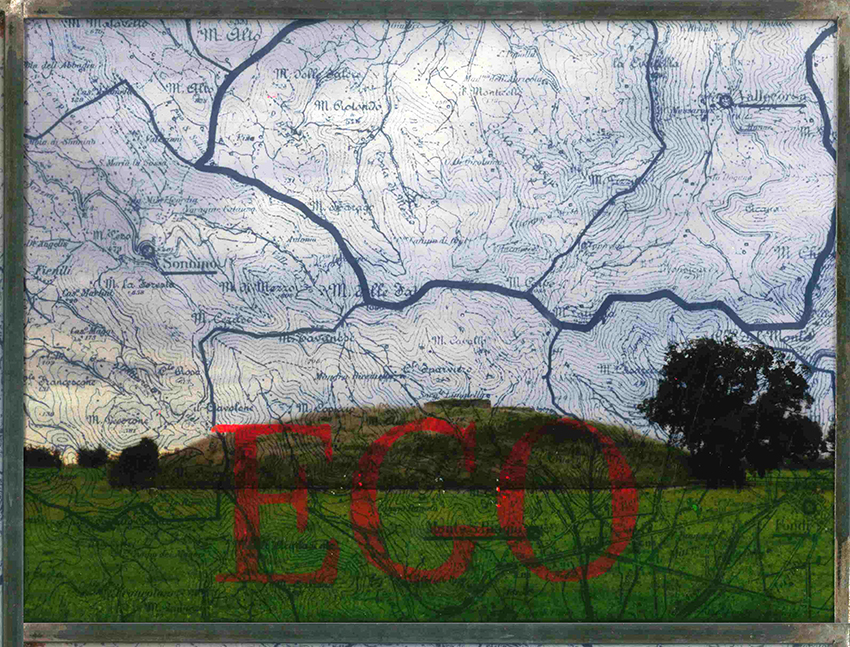

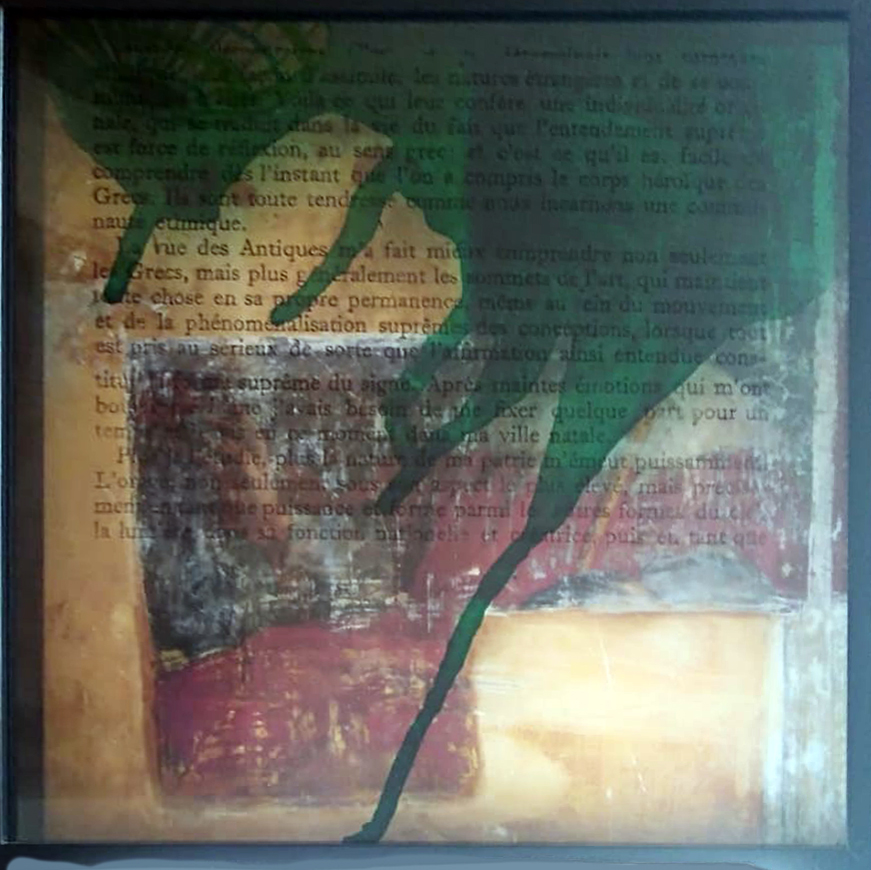

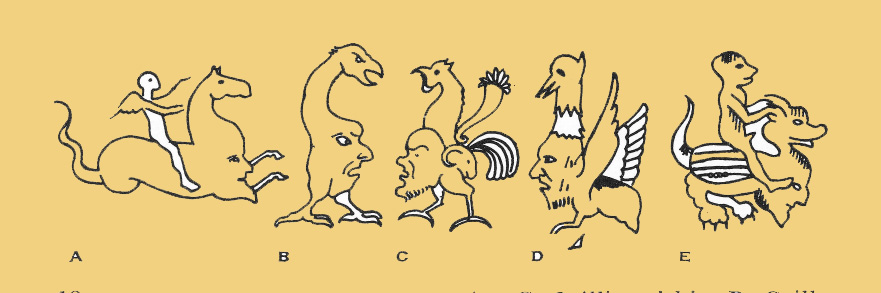

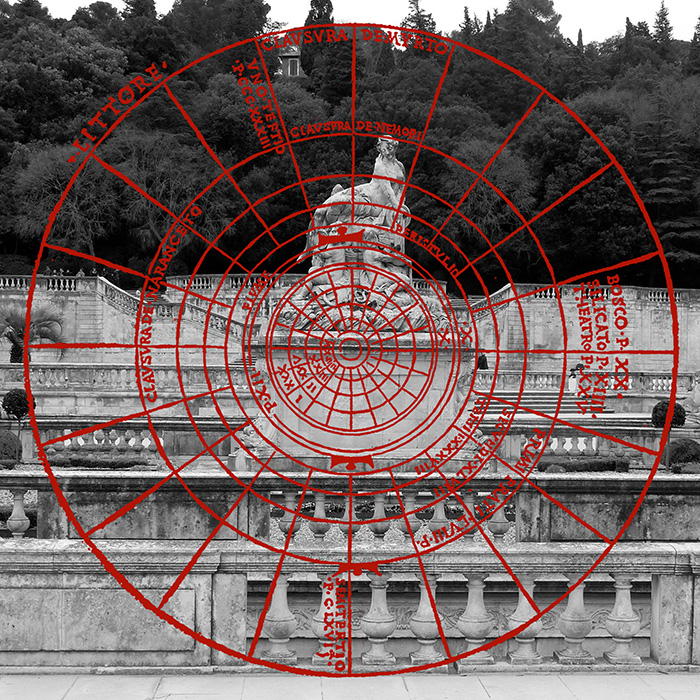

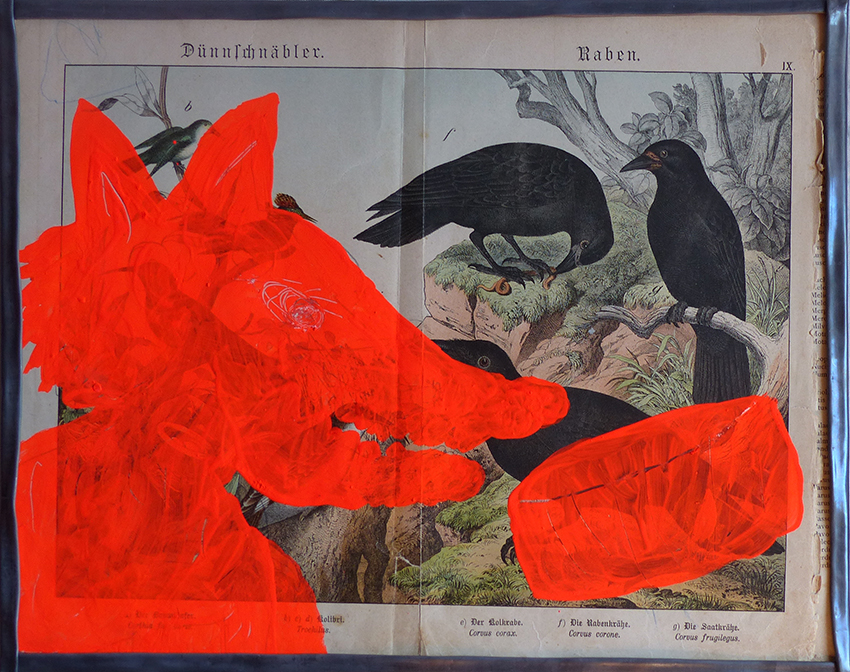

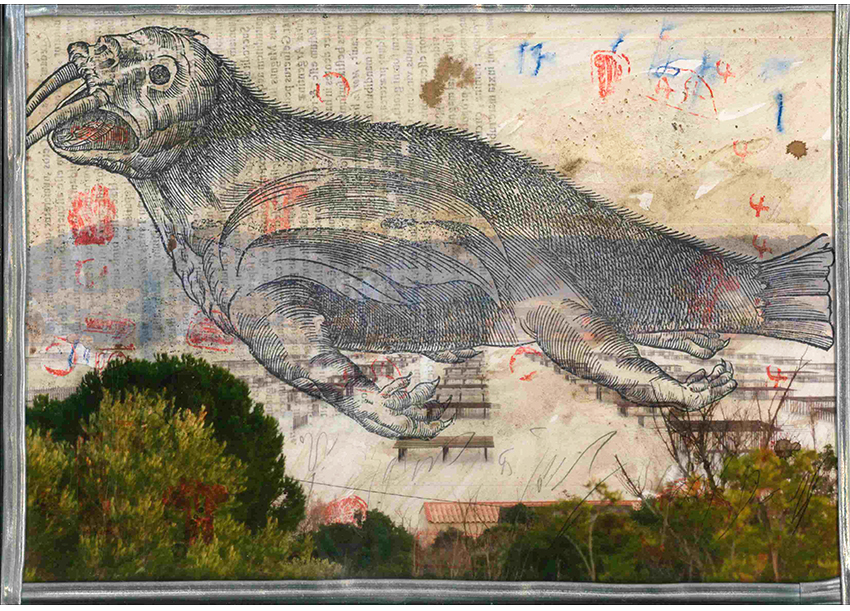

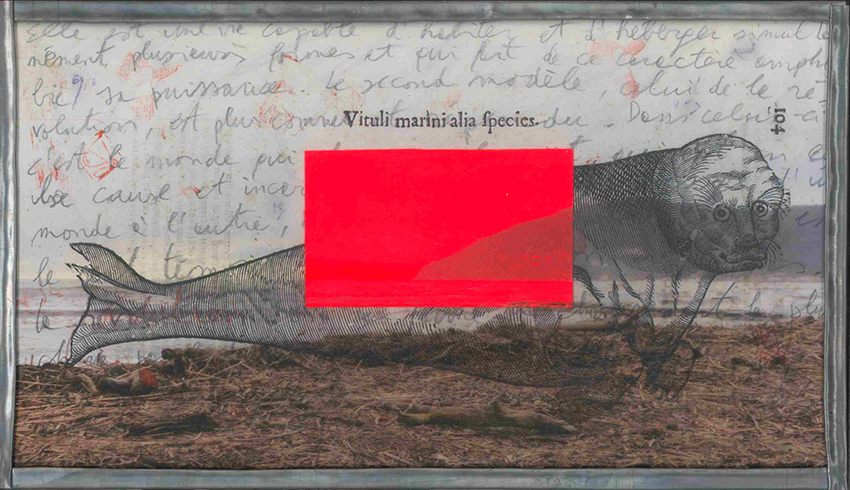

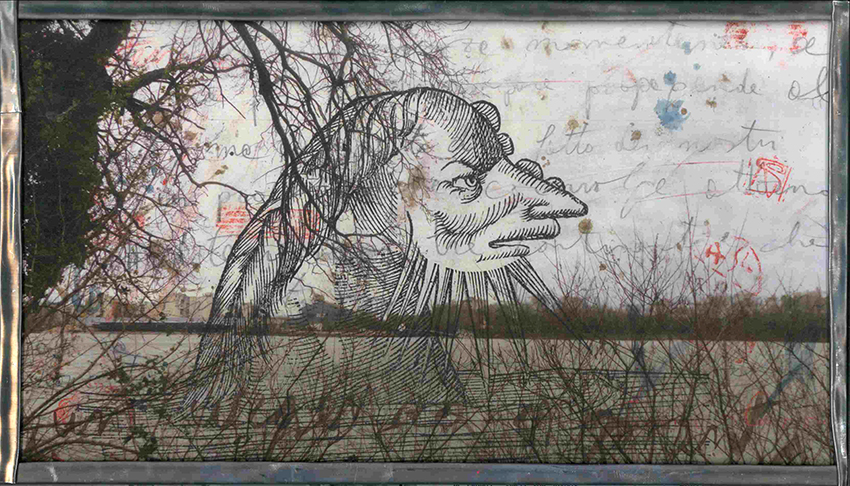

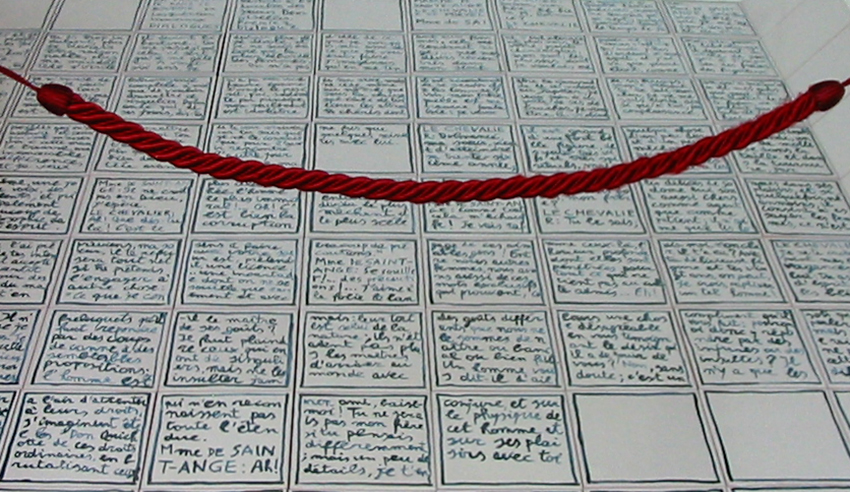

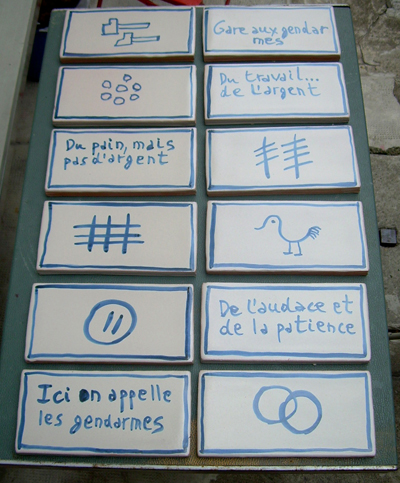

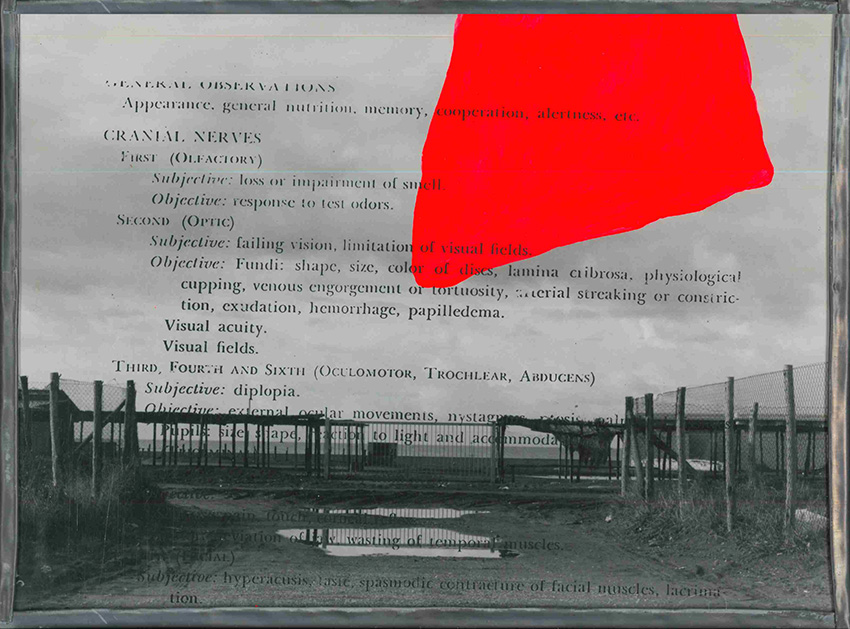

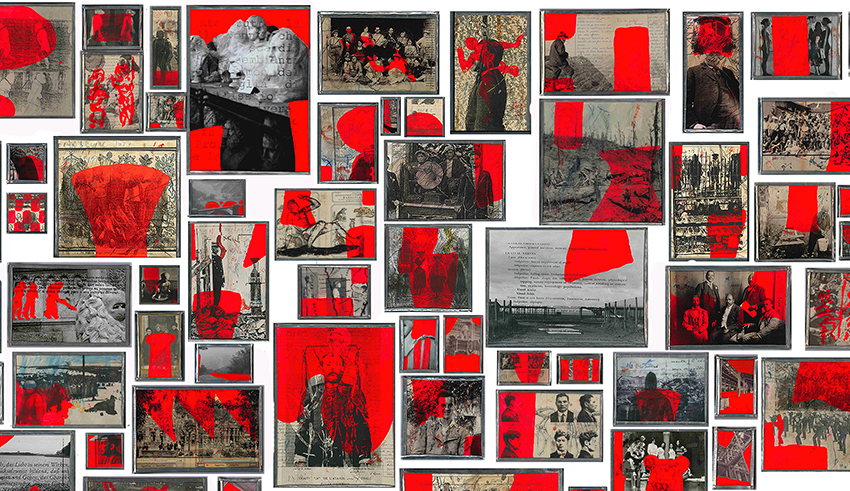

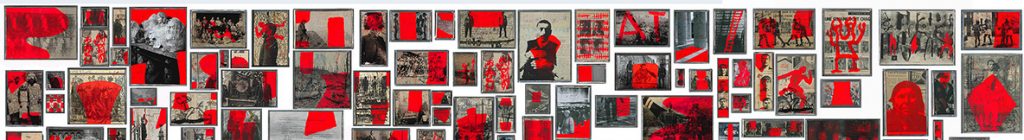

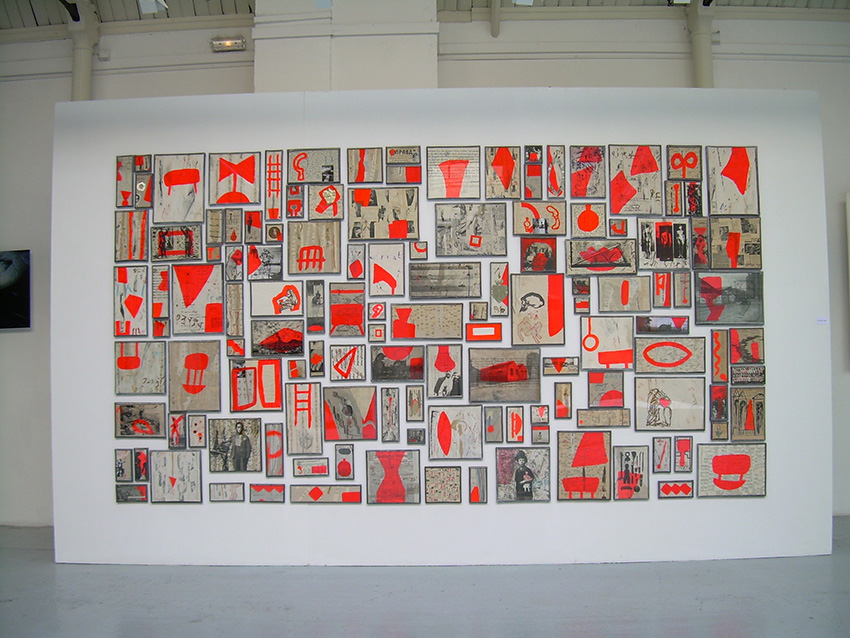

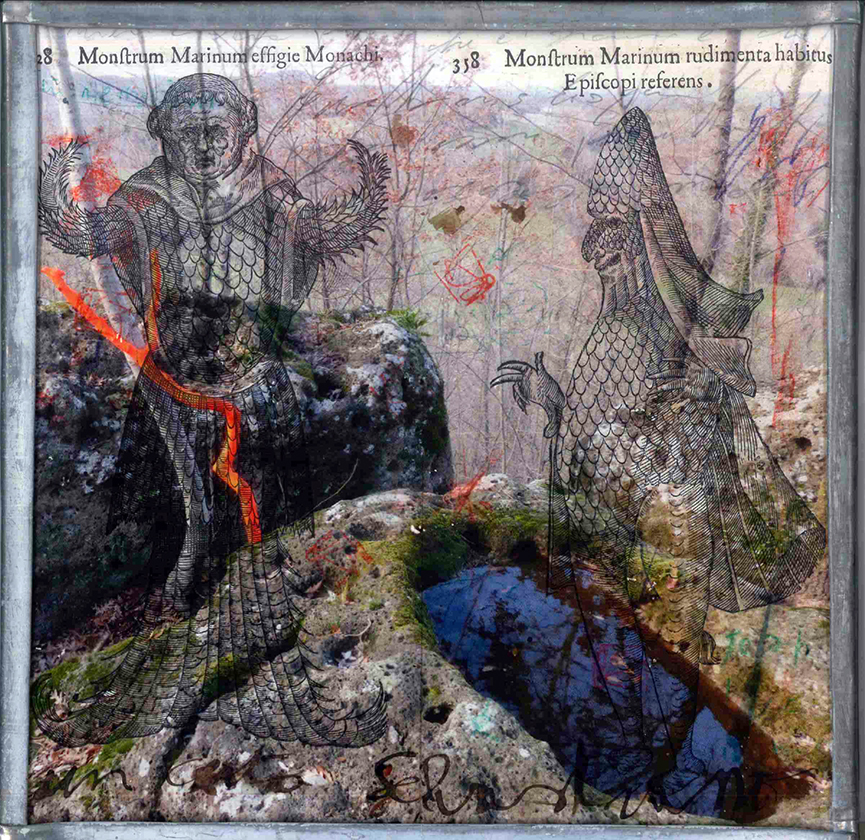

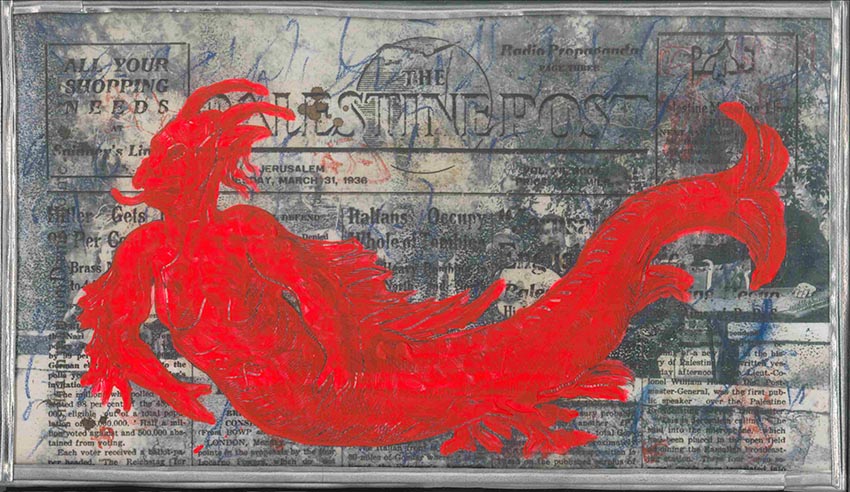

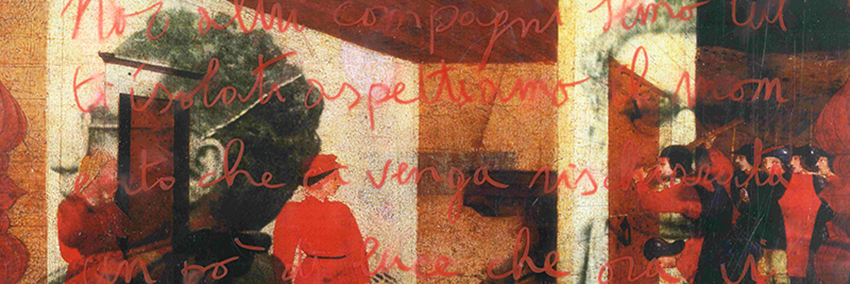

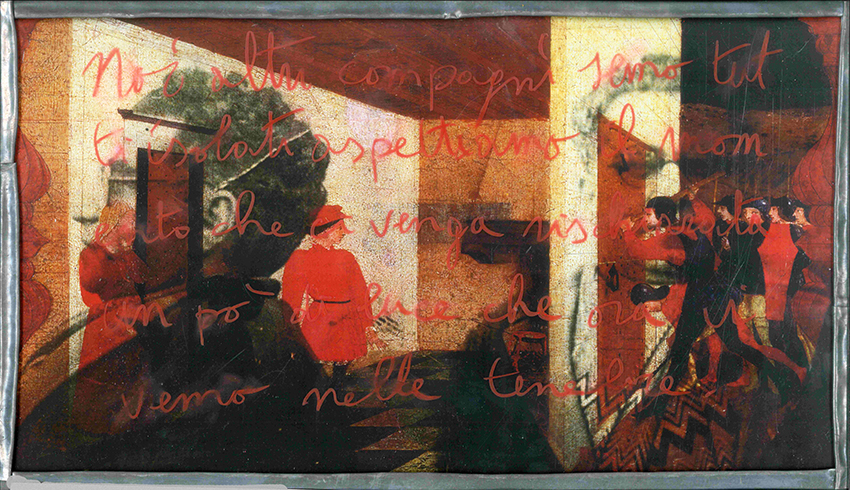

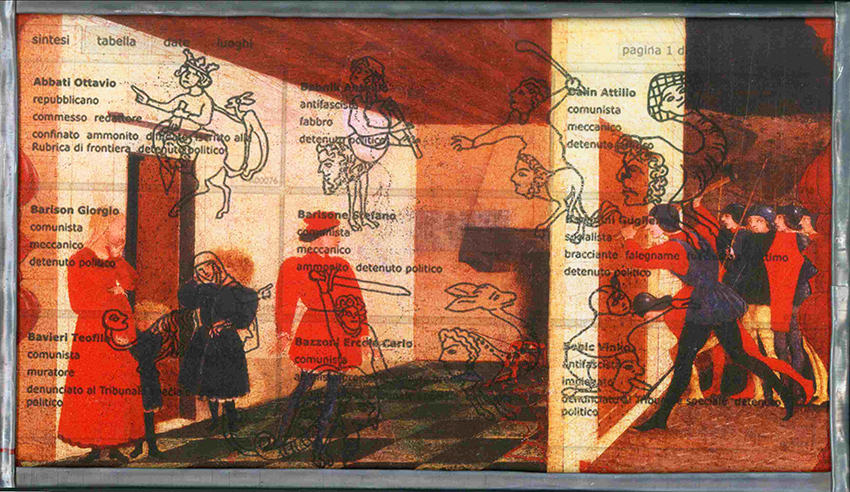

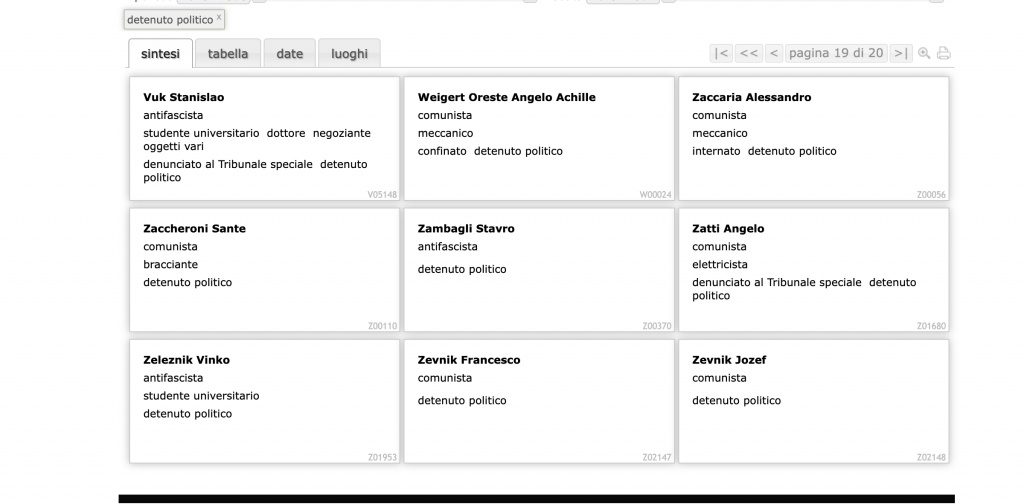

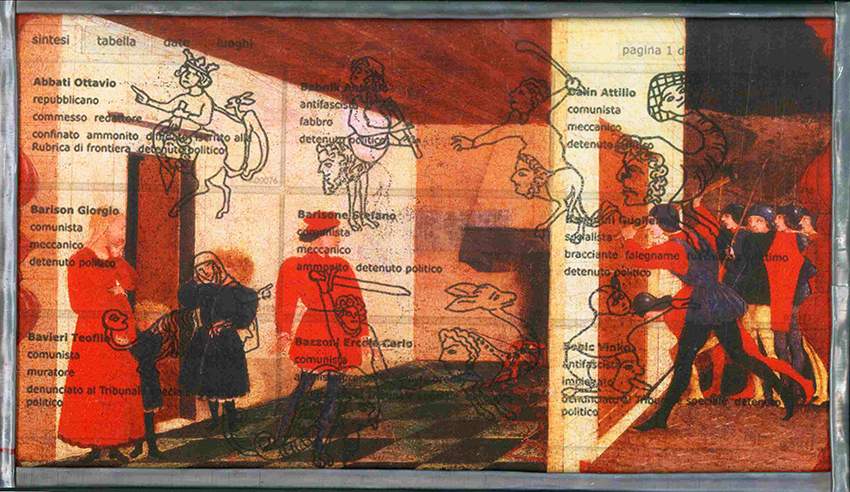

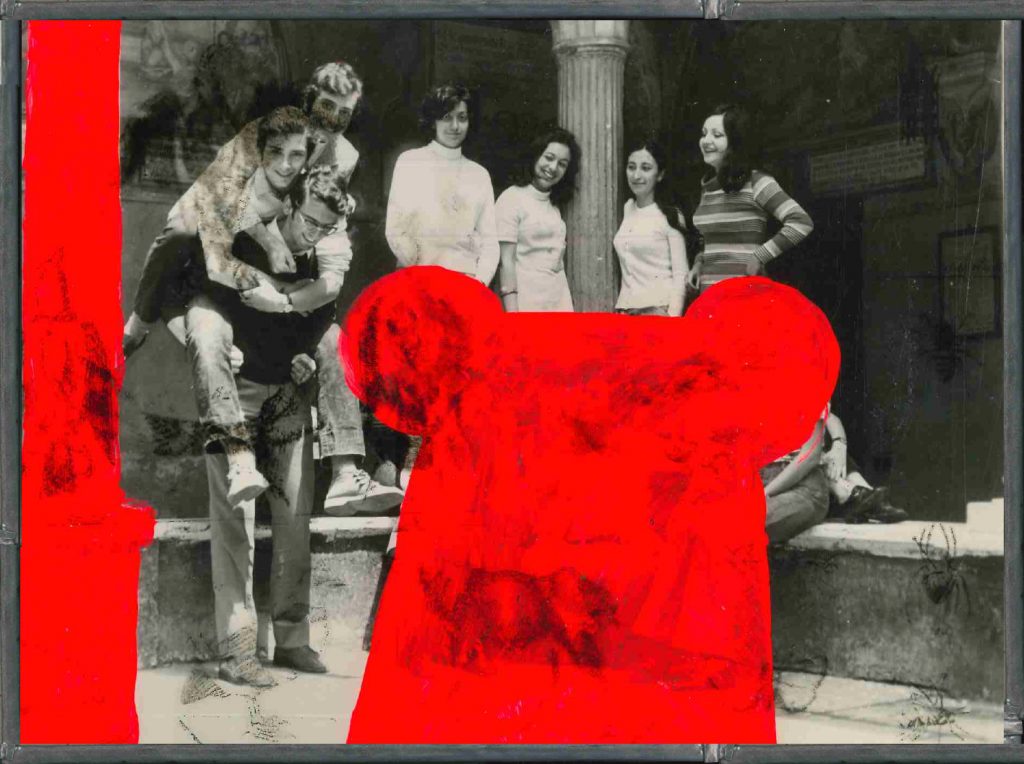

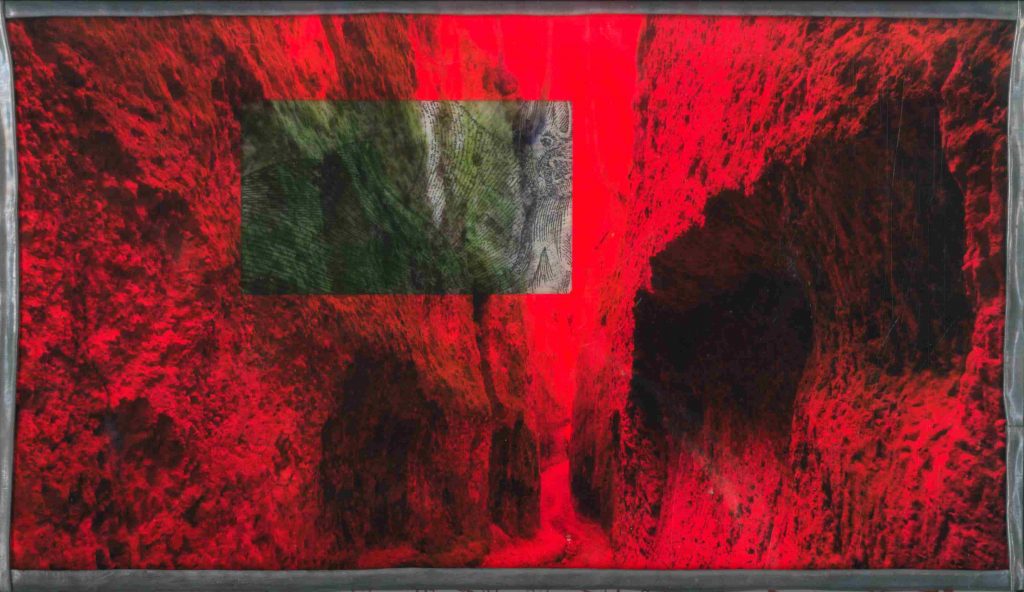

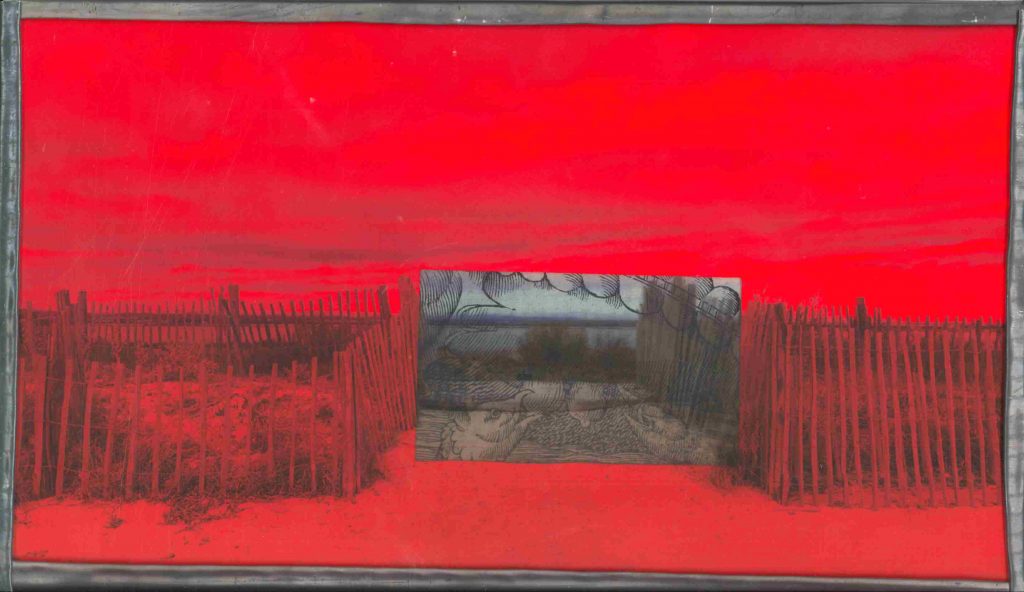

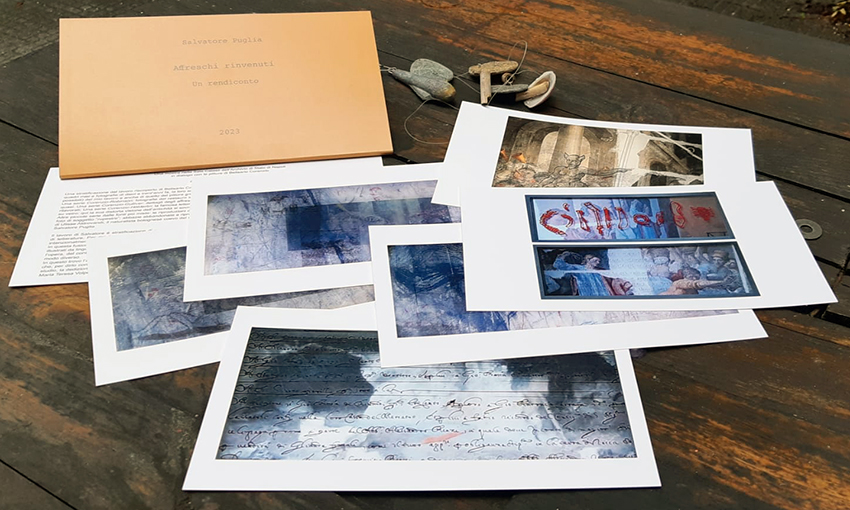

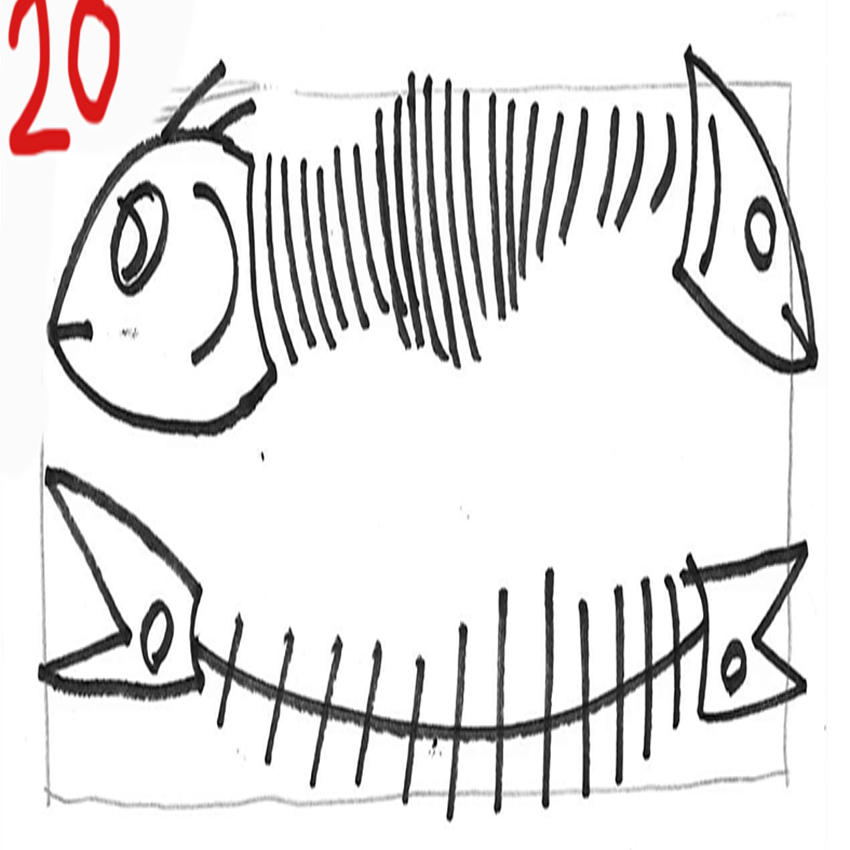

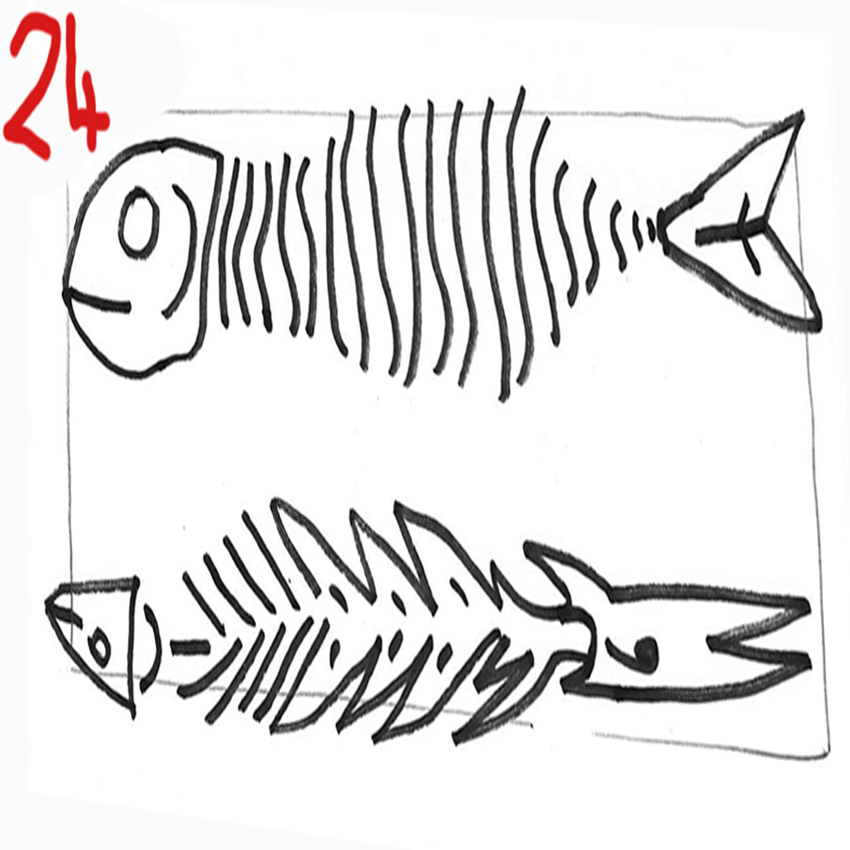

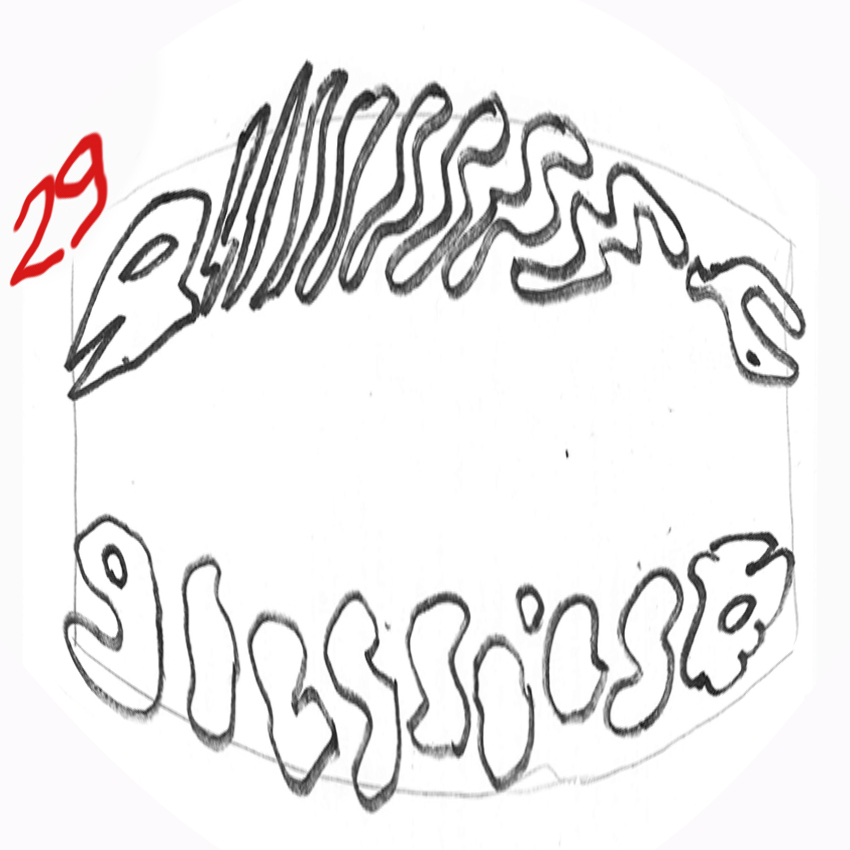

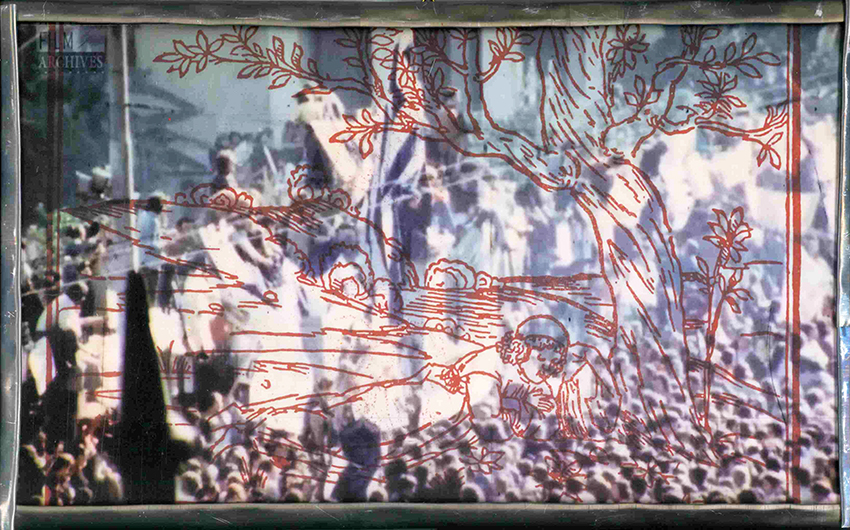

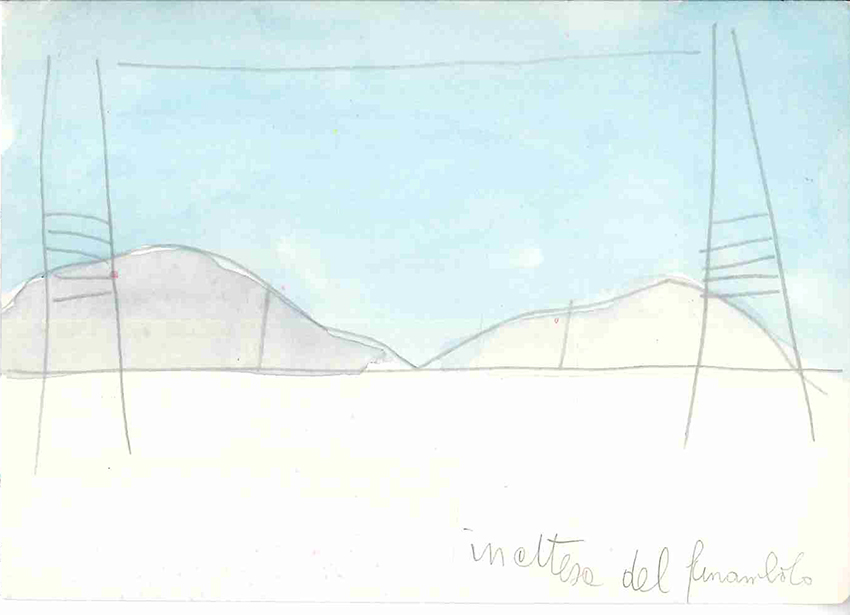

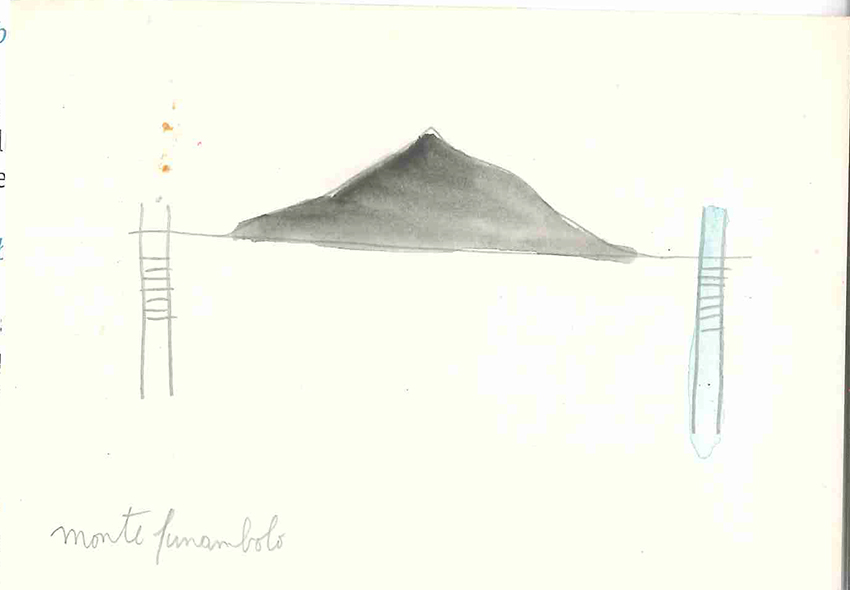

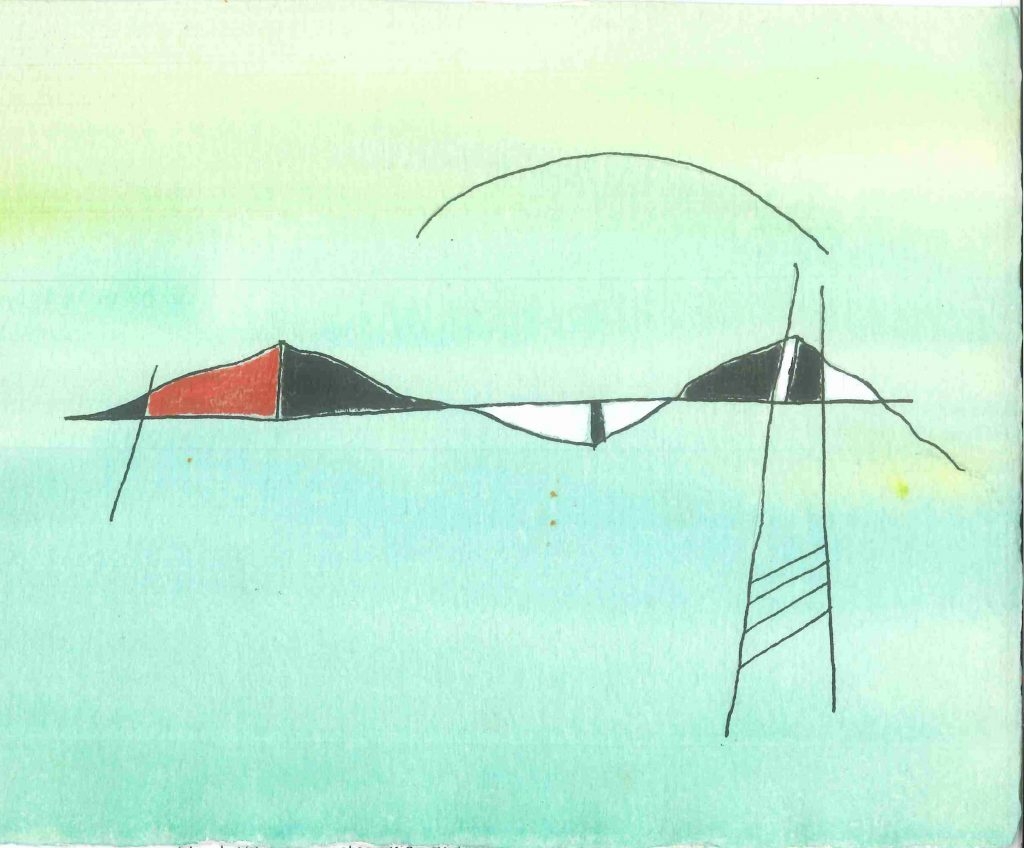

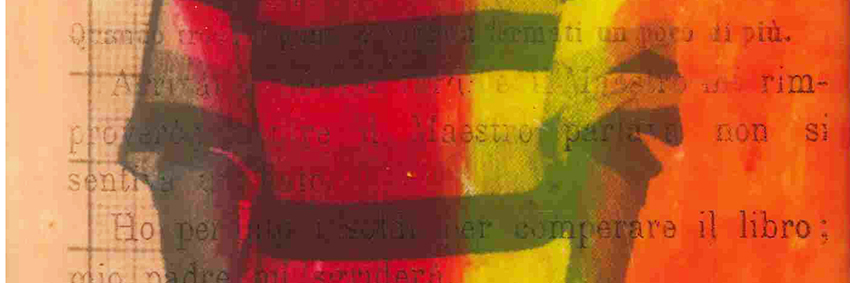

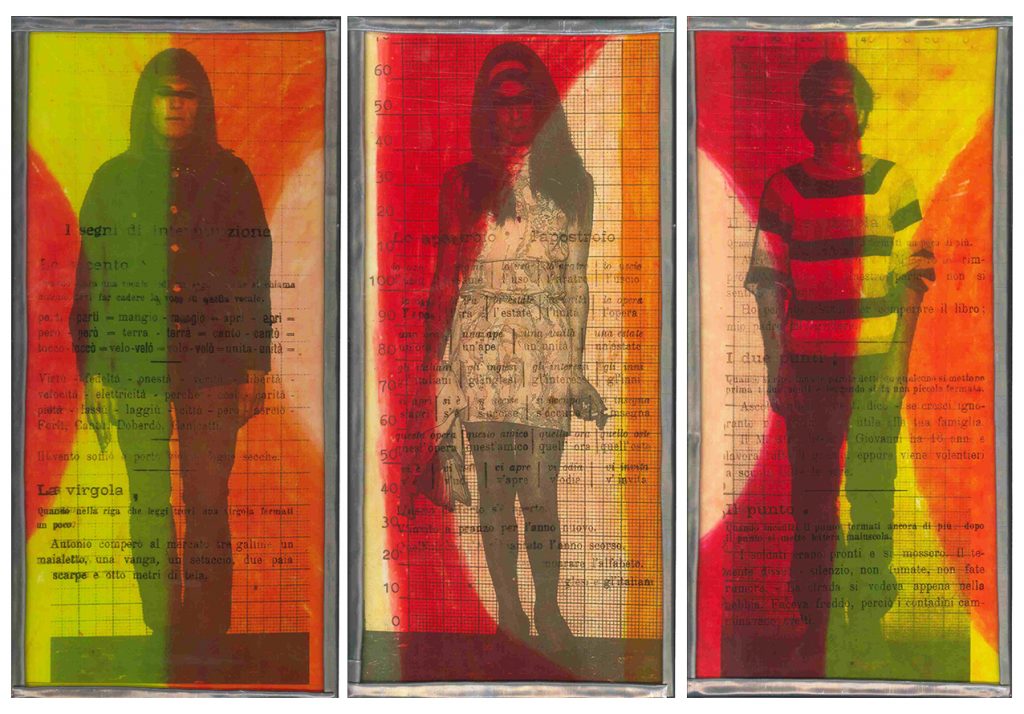

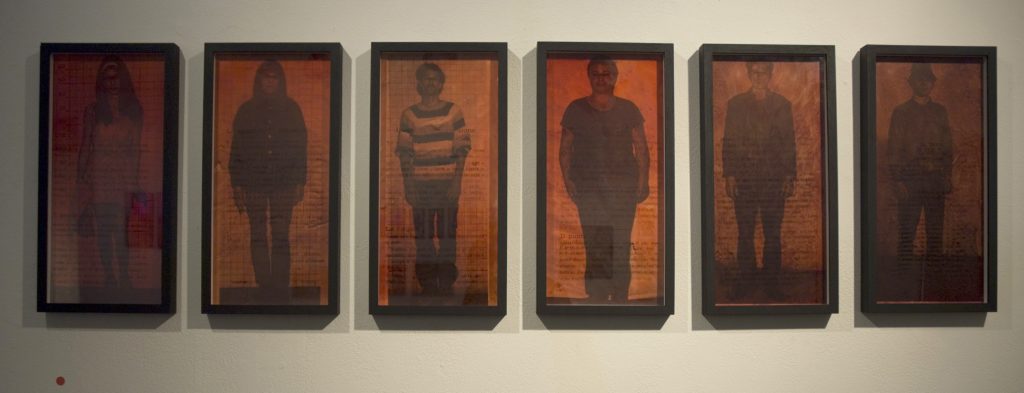

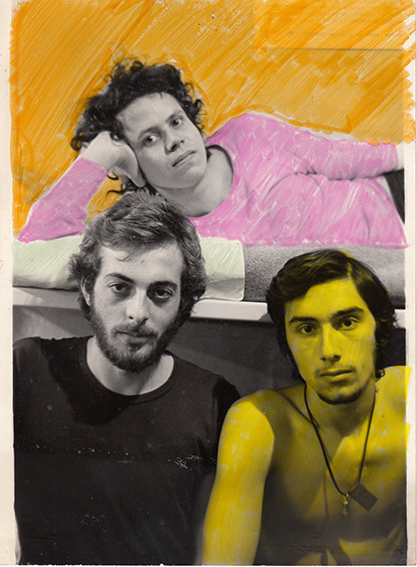

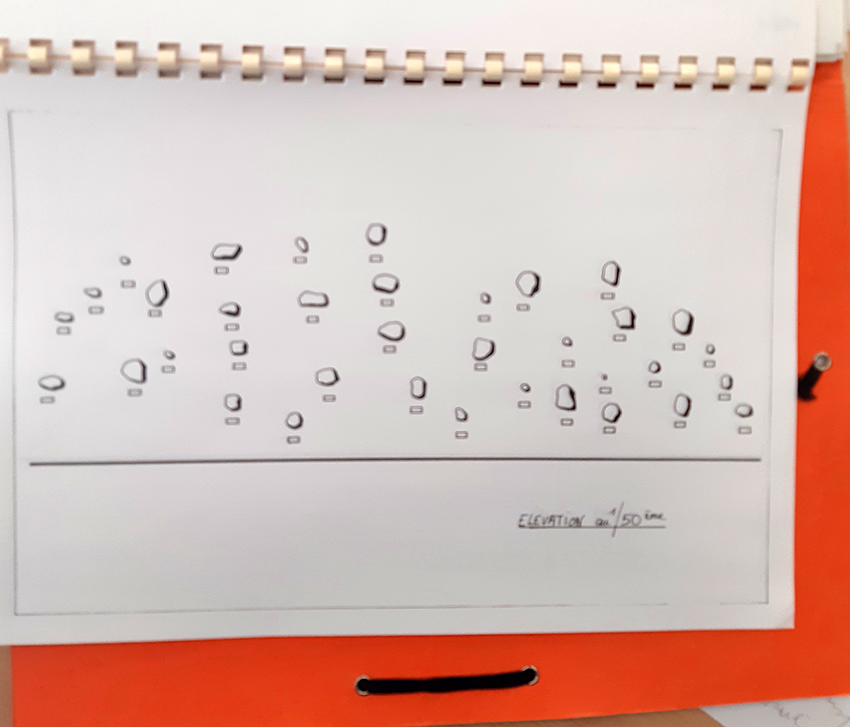

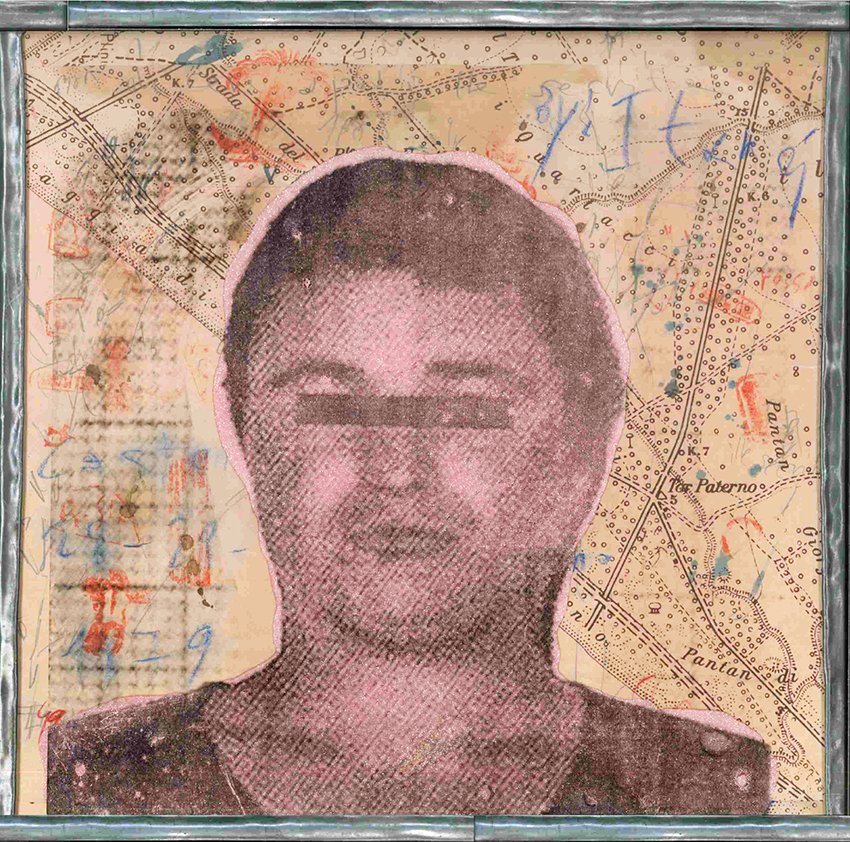

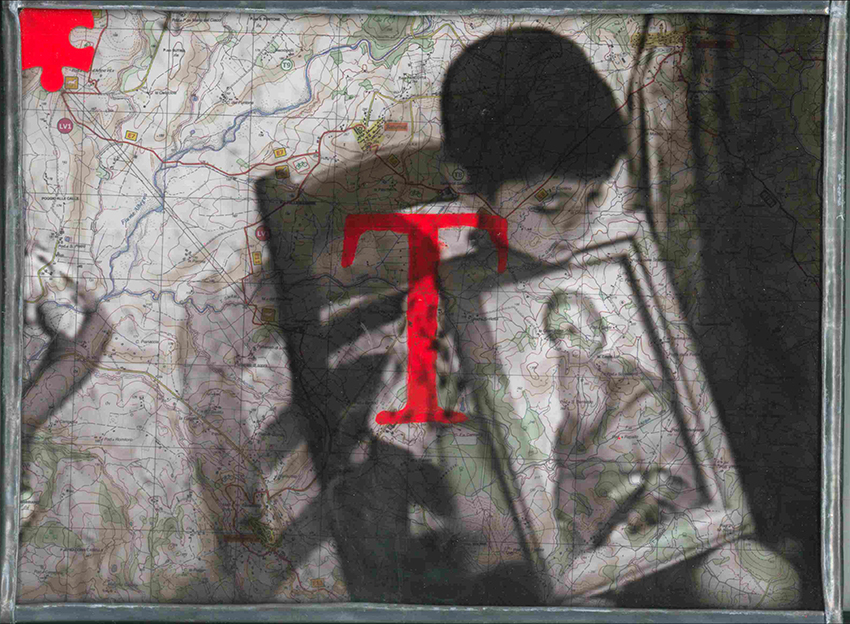

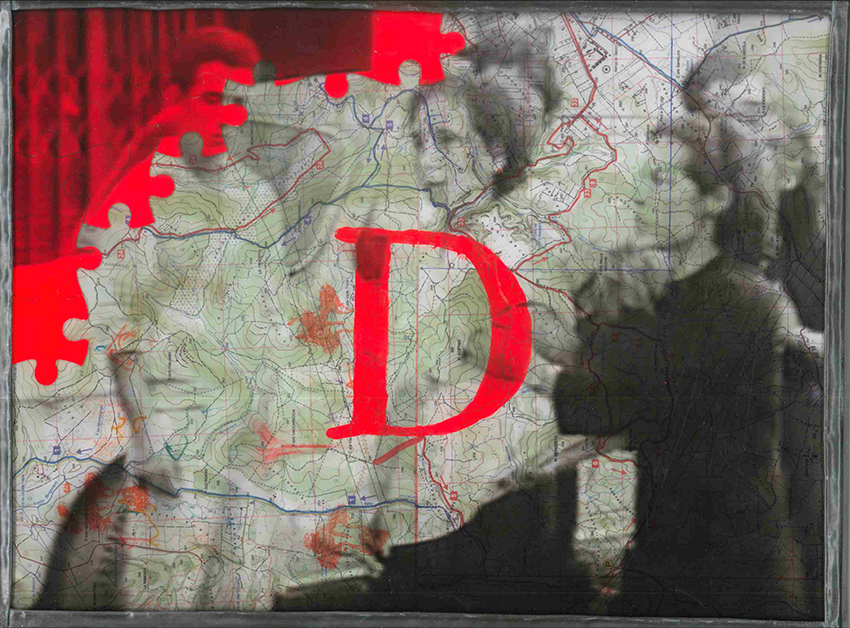

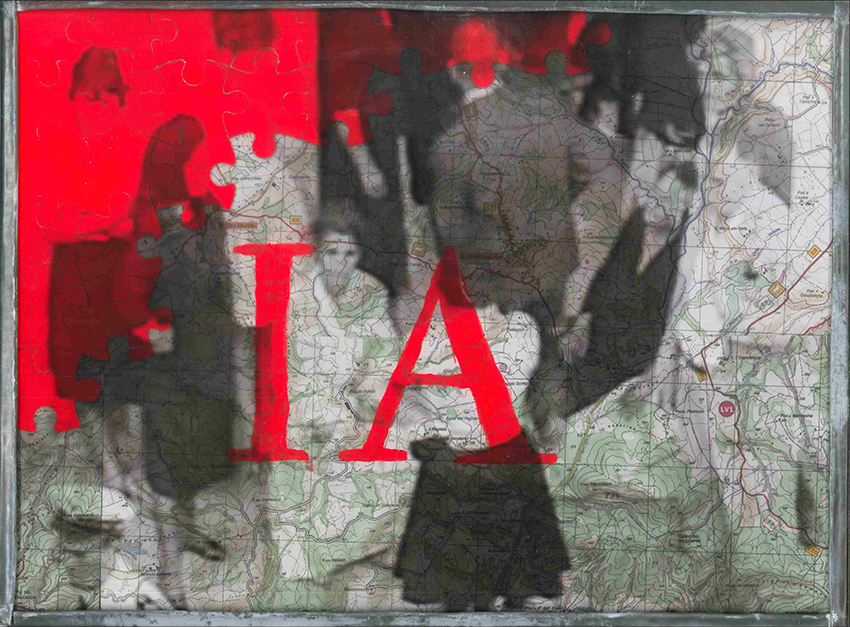

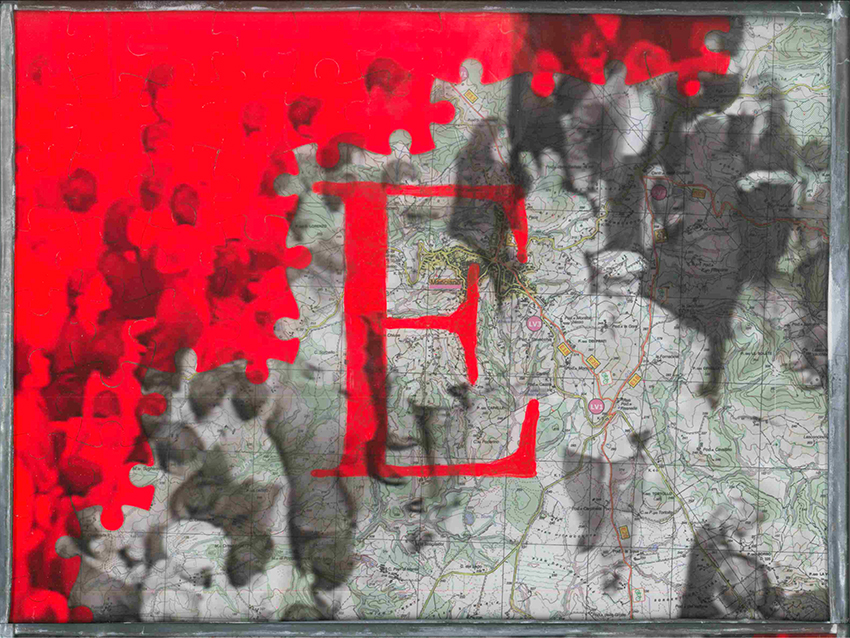

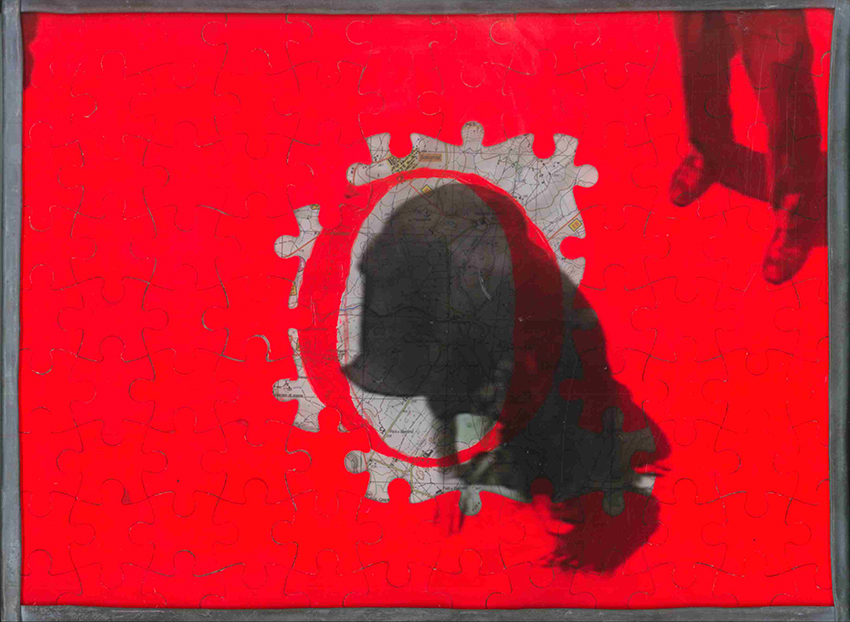

Il peso del mondo, 18×42, 2019 (elemento dell’installazione Millenovecento 2018-2021).

Il peso del mondo, 18×42, 2019 (elemento dell’installazione Millenovecento 2018-2021).

Il mio ‘’noi’’, all’altro estremo, sarebbe quello di un’umanità comune, quella cui fanno appello l’ONG La Cimade e Edwy Plenel all’indomani dell’adozione al parlamento francese (con i voti della destra e dell’estrema destra) di una legge contro l’immigrazione che avrà valore storico (19 dicembre 2023).

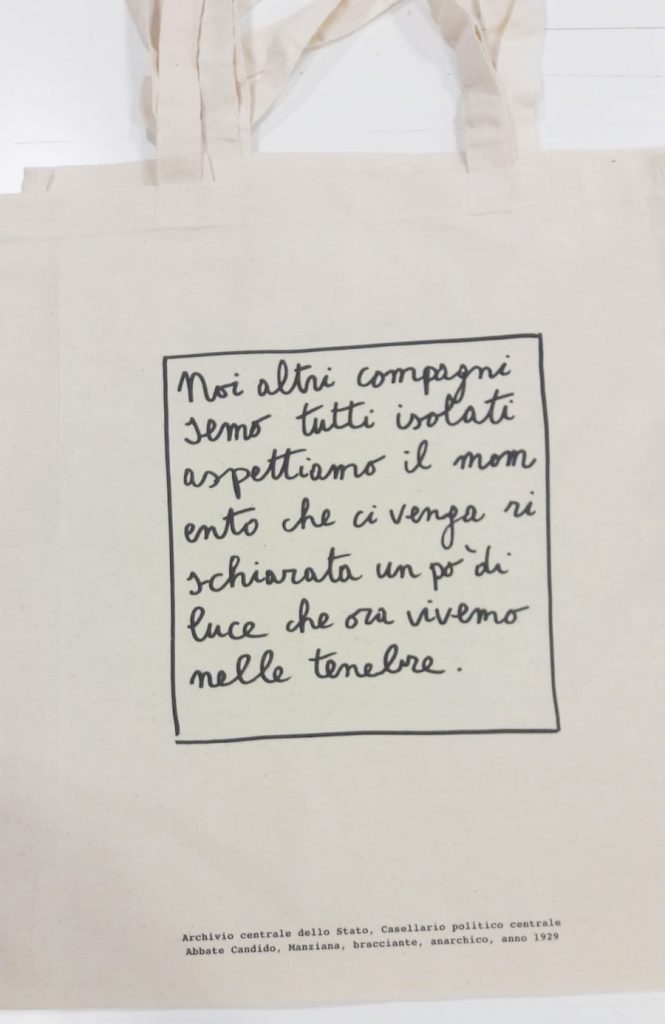

Mi piace ridire il “noialtri” del compagno di Manziana, che è un modo di dire “noi” che non conosco in altre lingue (neanche nel nosotros spagnolo e portoghese). Lo voglio leggere in altro modo che non l’identitario e caciarone ‘’noantri’’ (”fra di noi”): noi, altri.

Rivengo alla traduzione francese: « La crise consiste justement dans le fait que l’ancien meurt et que le nouveau ne peut pas naître : pendant cet interrègne on observe les phénomènes morbides les plus variés » (Cahiers de prison, traduction sous la responsabilité de Robert Paris, Gallimard, 1996 : Cahier 3, §34, p. 283).

Quanto a quella inglese, è certo che ‘’ now is the time of monsters’’ è ben più seducente che ‘’in this interregnum, a wide variety of morbid phenomena occur’’ (per una recente analisi anglofona della frase gramsciana rimando al saggio di Gilbert Achcar, ‘’Morbid Symptoms: What Did Gramsci Really Mean?’’, in: Notebooks: The Journal for Studies on Power, pubblicato Online nel febbraio 2022).

E Achcar, nel rimarcare l’imprecisione storica della diffusissima citazione (così come Plenel aveva sottolineato quella linguistica), riconosce la sua pertinenza nei tempi attuali: ‘’It is hence on the far right of the political spectrum that we are witnessing at present the most spectacular ‘morbid symptoms’ produced by the degeneration of capitalist politics. Applying Gramsci’s sentence to this reality is therefore legitimate, even if it is historically inaccurate.’’

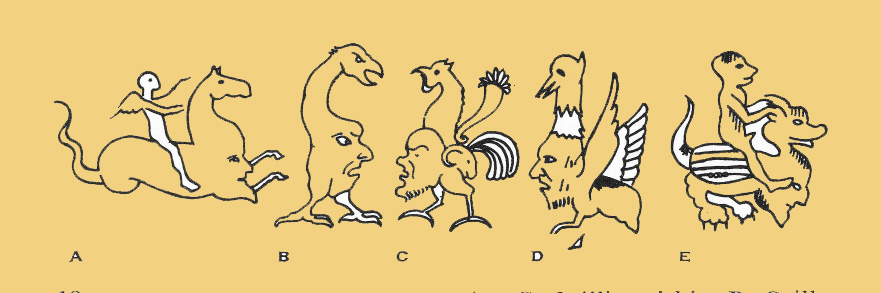

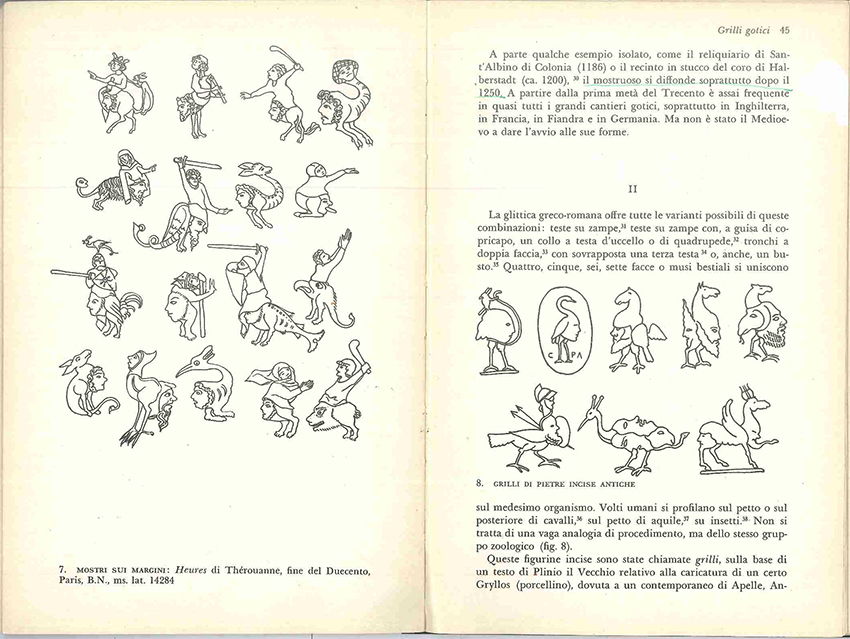

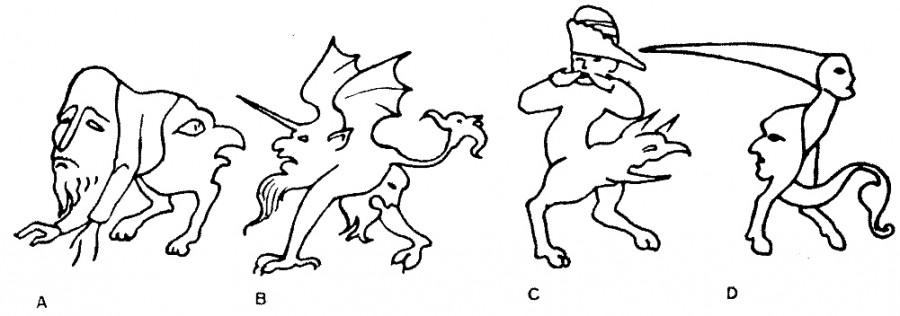

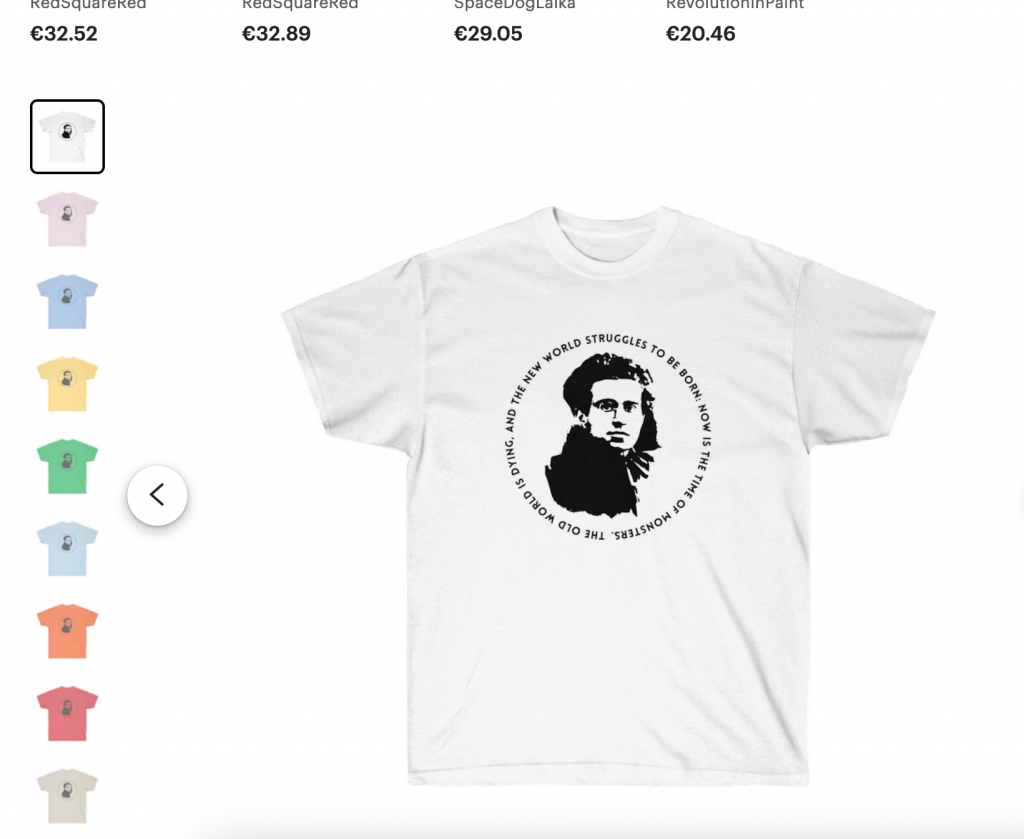

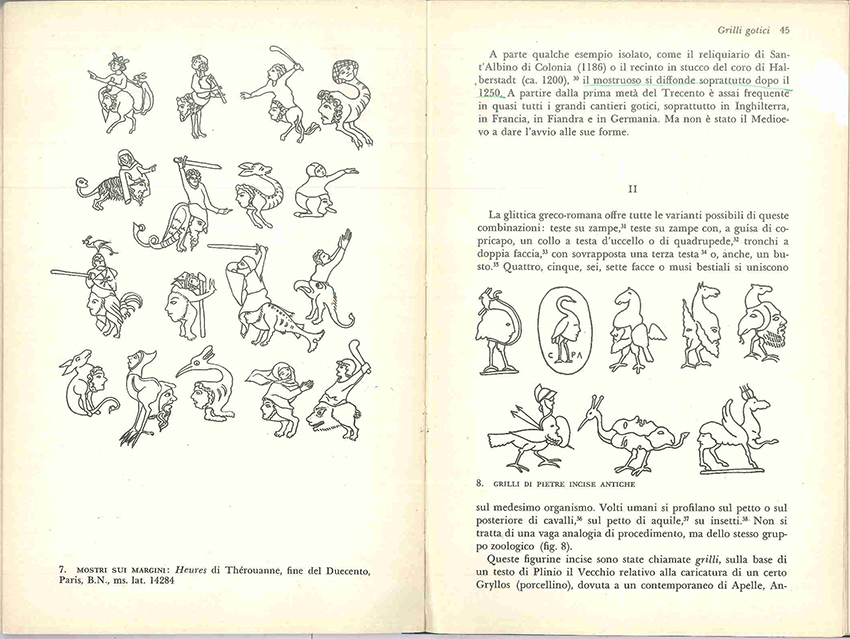

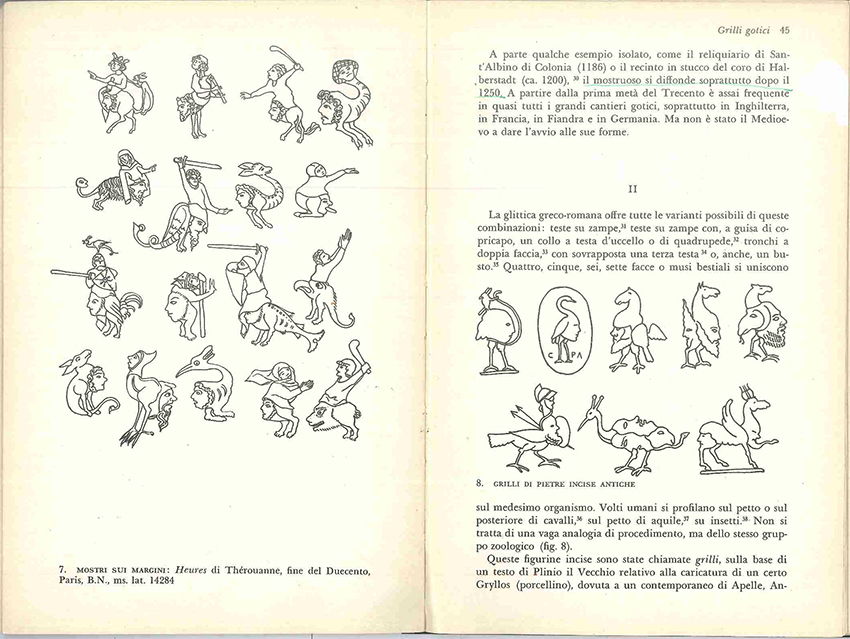

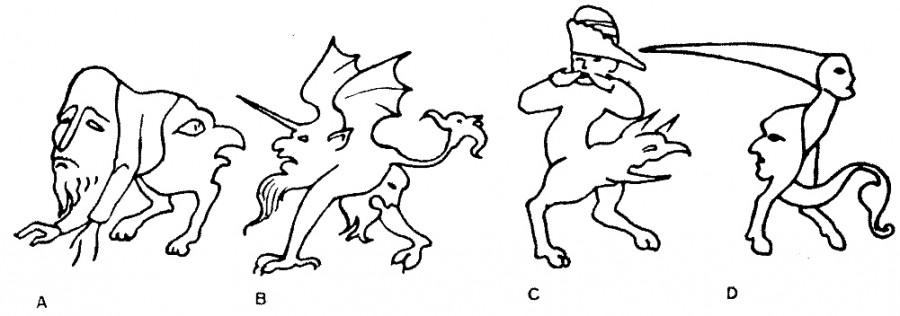

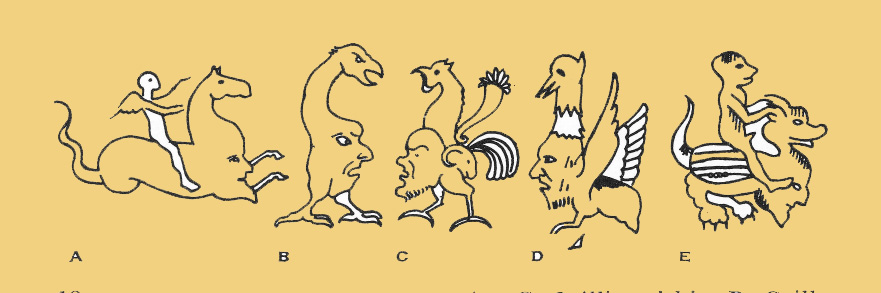

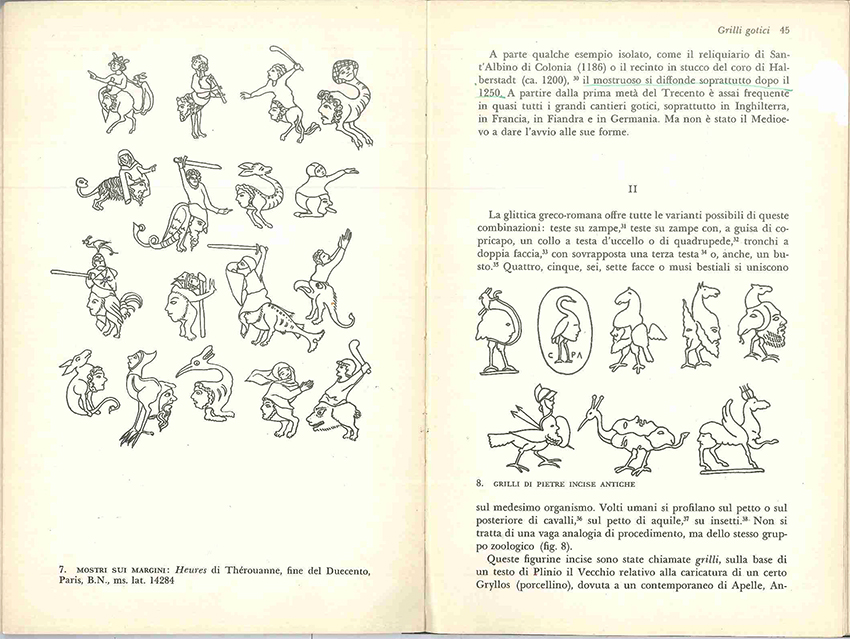

Nell’aprile del 1979 acquisii il volume di Jurgis Baltrusaitis Il Medioevo fantastico, Milano, Adelphi, 1973 e Oscar Studio Mondadori 1977, che rimane a tutt’oggi una fonte d’ispirazione importante per il mio lavoro. Non so se ci troviamo in un nuovo Medioevo, ma la visione di quello dello storico dell’arte lituano, in cui mondi apparentemente separati e sconosciuti l’uno all’altro si rivelano teatri di scambio culturale, è una visione cui tengo tuttora.

Nell’aprile del 1979 acquisii il volume di Jurgis Baltrusaitis Il Medioevo fantastico, Milano, Adelphi, 1973 e Oscar Studio Mondadori 1977, che rimane a tutt’oggi una fonte d’ispirazione importante per il mio lavoro. Non so se ci troviamo in un nuovo Medioevo, ma la visione di quello dello storico dell’arte lituano, in cui mondi apparentemente separati e sconosciuti l’uno all’altro si rivelano teatri di scambio culturale, è una visione cui tengo tuttora.

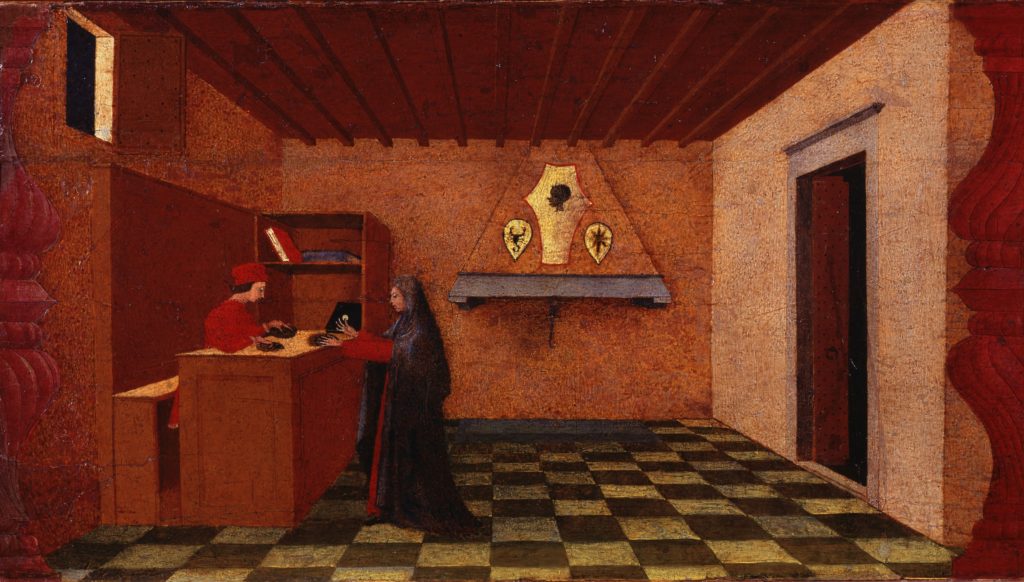

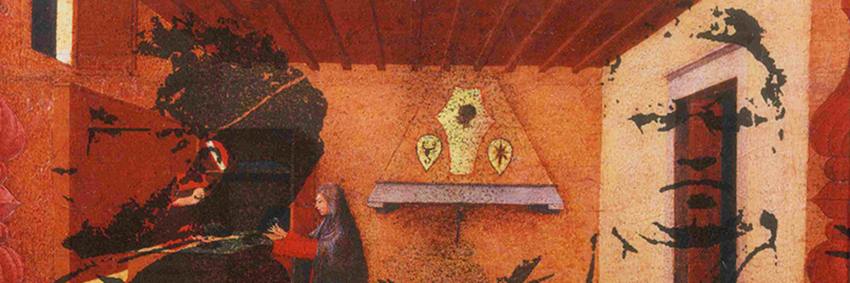

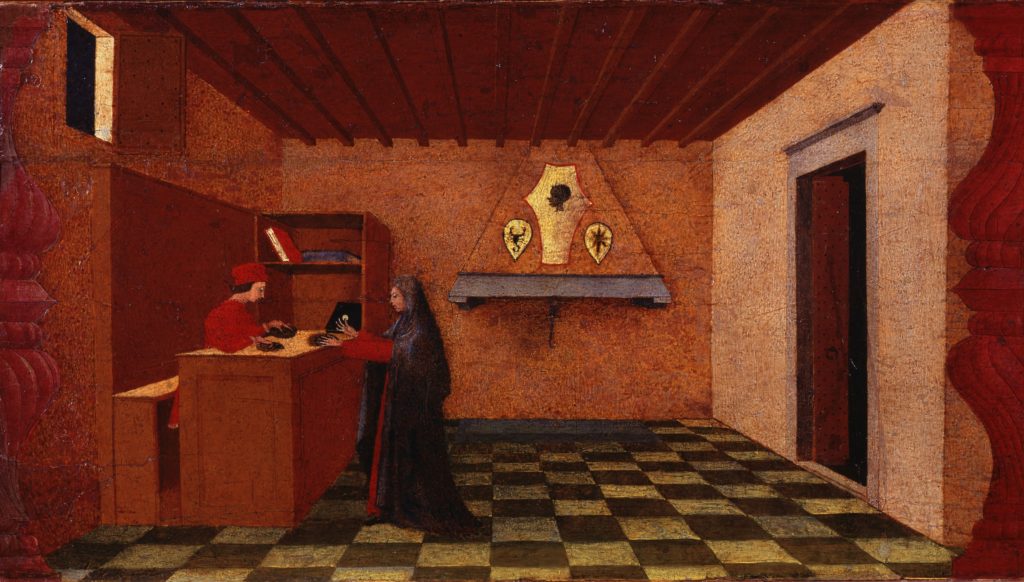

Suppongo che il Baltrusaitis mi occorresse come appoggio iconografico per una ricerca in corso sulla predella dell’Ostia profanata di Paolo Uccello, ricerca che avrebbe dovuto divenire un Diplôme d’Études Approfondies à l’École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, ciò che mai non divenne, essendo stato il 1980 non solo l’anno del mio primo soggiorno a Parigi ma anche quello dei miei primi tentativi artistici.

Ripensando al Paolo Uccello che in quella fine degli anni Settanta mi occupava insieme con i prodigi mostruosi di Baltrusaitis, mi è chiaro ora che cercavo dalle parti della normalità e dell’alterità, del ‘’noi’’ e del ‘’loro’’.

Ripensando al Paolo Uccello che in quella fine degli anni Settanta mi occupava insieme con i prodigi mostruosi di Baltrusaitis, mi è chiaro ora che cercavo dalle parti della normalità e dell’alterità, del ‘’noi’’ e del ‘’loro’’.

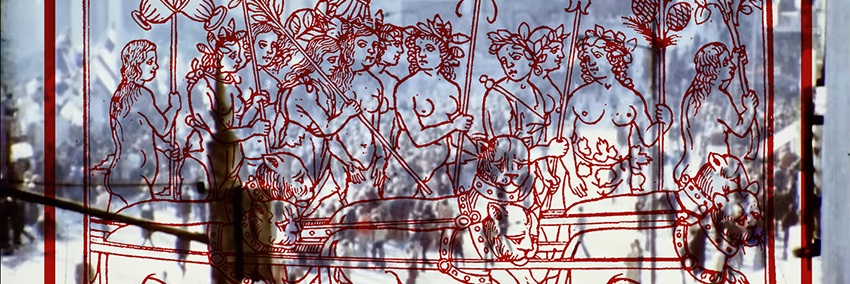

Gli storici dell’arte, in particolare Marilyn Aronberg Lavin (1967) et Jean-Louis Schefer (2007) hanno mostrato come la predella di Urbino, che narra la storia di una donna ‘’gentile’’ che procura un’ostia consacrata a un usuraio ebreo, il quale tenta di distruggerla col fuoco e col ferro e infine viene scoperto e suppliziato insieme con la sua famiglia, mentre l’anima della donna, dopo una lotta fra angeli e demoni, viene malgrado tutto salvata dall’inferno, si inscrive in un programma degli ordini mendicanti di edificazione dei Monti di Pietà, in alternativa al monopolio dei prestiti su pegno da parte degli usurai, maggioritariamente ebrei. Si trattava inoltre di affermare il recente dogma della transustantazione (Decreto sull’Eucaristia, 1551). La stigmatizzazione dell’altro era necessaria a questo programma.

L’essere di ‘’noi’’ o di ‘’loro’’ lo vivevo costantemente in quegli anni. Essendo buona parte dei miei amici e mentori di origine ebraica, ed essendo quello in Italia il momento di un rinnovamento dell’identità ebraica, anche nella critica al governo israeliano, mi capitava di trovarmi fuori posto e imbarazzante per gli altri, in una cena o un pranzo fra amici, in cui evidentemente ‘’non c’entravo’’. Ricordo come, nel giugno del 1982, al momento dell’invasione del Libano e del massacro di Sabra e Shatila, mi trovai a sentirmi dire: ‘’ma allora sono gli ebrei!’’ (vedi, al soggetto: Andrea Maori, Marta Brachini, Ebraismo: ricostruire dalle macerie L’associazionismo ebraico e di amicizia verso Israele nelle informative di polizia, Nuovi equilibri, Viterbo 2013, in particolare l’analisi del dibattito, nel luglio 1982 sulle pagine de Il Manifesto, fra Giorgio Agamben e Rossana Rossanda e il successivo intervento su l’Unità di Natalia Ginzburg).

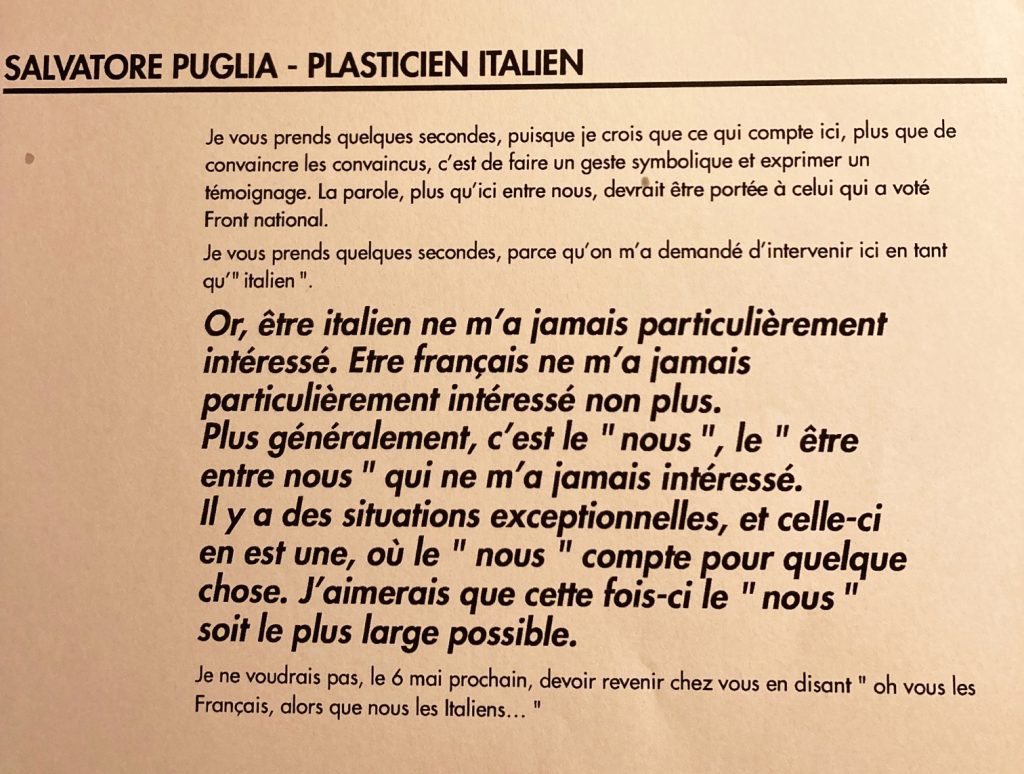

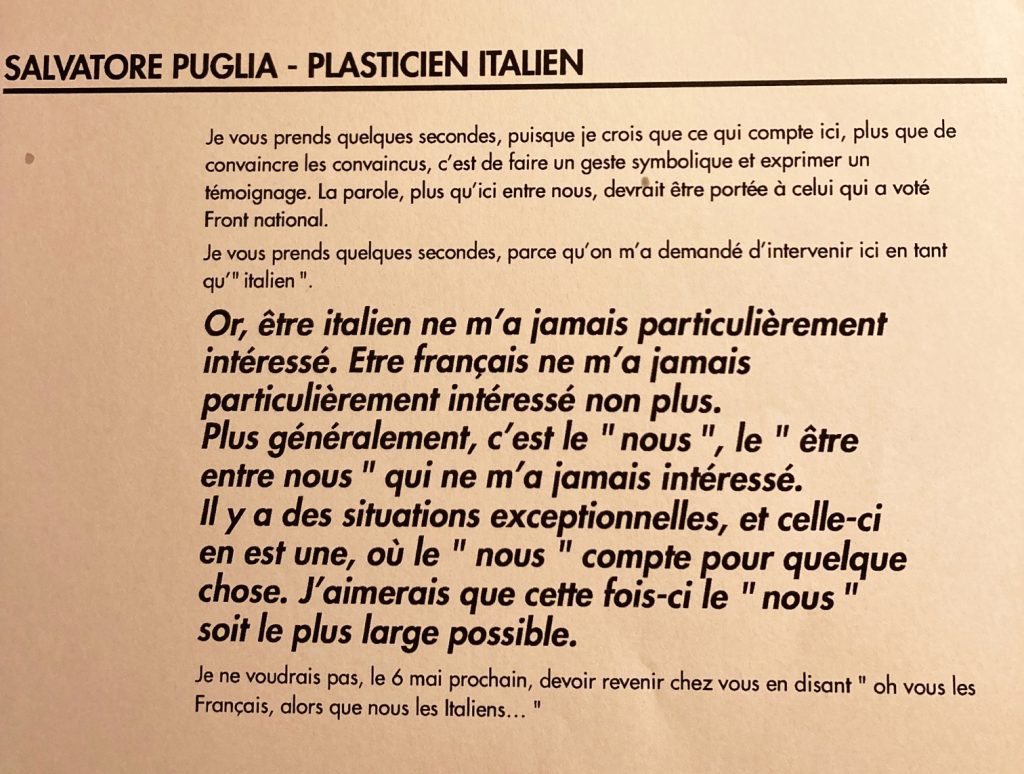

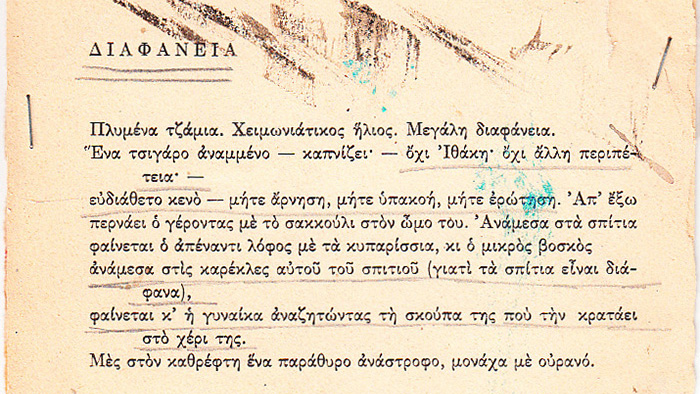

Venti anni dopo, il 1° maggio 2002 – mi trovavo a vivere in Francia – partecipai a una Tribune publique, nella sala della Laiterie di Strasburgo, in occasione del secondo turno delle elezioni presidenziali francesi e dell’appello a votare Chirac per impedire l’elezione di Le Pen. Si era numerosi sulla scena a intervenire, uno dopo l’altro con i mezzi d’espressione di cui ognuno disponeva. Un collega artista portò una marionetta fatta di pezzi di scarto, che faceva parlare come fosse un ventriloquo. Io fui tra gli ultimi a parlare, in un’aula che si stava svuotando. Un’amica ha conservato gli atti di quella giornata:

Venti anni dopo, il 1° maggio 2002 – mi trovavo a vivere in Francia – partecipai a una Tribune publique, nella sala della Laiterie di Strasburgo, in occasione del secondo turno delle elezioni presidenziali francesi e dell’appello a votare Chirac per impedire l’elezione di Le Pen. Si era numerosi sulla scena a intervenire, uno dopo l’altro con i mezzi d’espressione di cui ognuno disponeva. Un collega artista portò una marionetta fatta di pezzi di scarto, che faceva parlare come fosse un ventriloquo. Io fui tra gli ultimi a parlare, in un’aula che si stava svuotando. Un’amica ha conservato gli atti di quella giornata:

Salvatore Puglia – plasticien italien.

Je vous prends quelques secondes, puisque je crois que ce qui compte ici, plus que de convaincre les convaincus, c’est de faire un geste symbolique et exprimer un témoignage. La parole, plus qu’ici entre nous, devrait être portée à celui qui a voté Front national.

Je vous prends quelques secondes, qu’on m’a demandé d’intervenir ici en tant qu’‘’italien’’. Or, être italien ne m’a jamais particulièrement intéressé. Être français ne m’a jamais particulièrement intéressé non plus.

Plus généralement, c’est le ‘’nous’’, le ‘’être entre nous’’ qui ne m’a jamais intéressé. (Qui avvertii una palpabile freddezza, fra il pubblico, riunitosi proprio per affermare una prima persona plurale). Il y a des situations exceptionnelles, et celle-ci en est une, où le ‘’nous’’ compte pour quelque chose. J’aimerais que cette fois-ci le ‘’nous’’ soit le plus large possible.

Je ne voudrais pas, le 6 mai prochain, devoir revenir chez vous en disant ‘’oh vous les Français, alors que nous les Italiens… ‘’

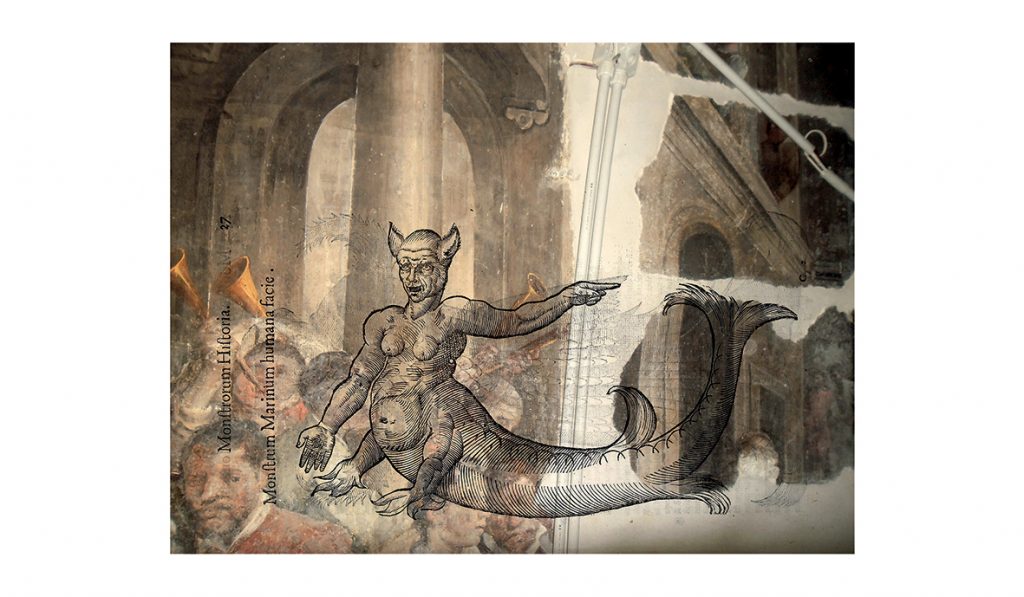

Torno al Medioevo fantastico. L’interesse di quest’opera è che, alla luce della sua conoscenza dell’arte orientale, Baltrusaitis dimostra come mondi che non sapevano neanche di conoscersi erano influenzati reciprocamente, almeno sul piano delle immagini: nei mostri e nelle bizzarrie medievali erano onnipresenti i motivi dell’arte islamica, buddista, cinese, oltre evidentemente all’eredità dell’antichità greco-romana, fino al soggetto dell’incontro fra I tre vivi e i tre morti, il quale ci sarebbe venuto dal Tibet.

Melfi, chiesa rupestre di santa Margherita. Taluni vedono nelle tre figure di sinistra Federico II di Svevia e suoi familiari in abiti da falconiere (vedi il sito Visioni dell’aldilà).

Melfi, chiesa rupestre di santa Margherita. Taluni vedono nelle tre figure di sinistra Federico II di Svevia e suoi familiari in abiti da falconiere (vedi il sito Visioni dell’aldilà).

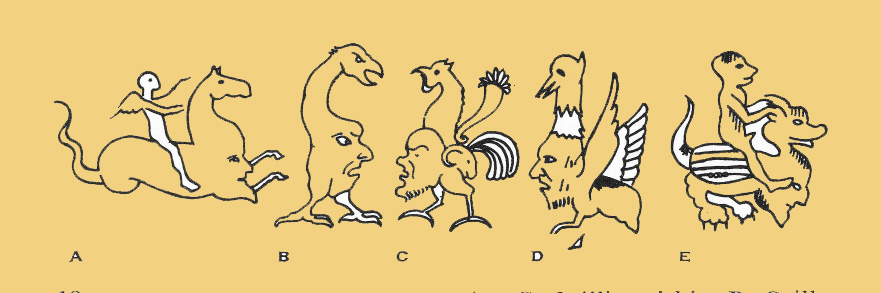

Trascrivo dal primo capitolo, ‘’Grilli gotici’’: “L’Antichità greco-romana possiede due volti: da una parte, un mondo di dèi e di uomini dove tutto è eroico e nobile nello schiudersi di una vita possente e organica, e, dall’altra, un mondo di esseri fantastici dalle origini complesse, venuti spesso da molto lontano, e che presentano mescolanze di corpi e di nature eterogenee. Eppure si tratta della medesima visione di un’epopea fatta di elementi e aspetti molteplici, che costituiscono un universo completo e unico.

Non così è nella storia delle sue sopravvivenze. Il Medioevo, che non ha mai perso contatto con l’antico sostrato, si volge ora verso l’uno, ora verso l’altro di questi aspetti.’’ (p. 39 dell’edizione 1979, traduzione di massimo Oldoni).

Mi chiedo se questa citazione non possa in qualche modo richiamare l’idea dell’interregno gramsciano.

Mi dico anche che nell’anno 2023 non abbiamo perso il contatto con il nostro sostrato, i mostri in noi. Ma, nell’opera di Baltrusaitis, trovo e trovavo l’idea che il mostro – recondito o acquisito che sia, preesistente o accolto – non è necessariamente ‘’morboso’’ e, anche, che una parte di mostruosità sia necessaria per poter comprendere quella degli altri.

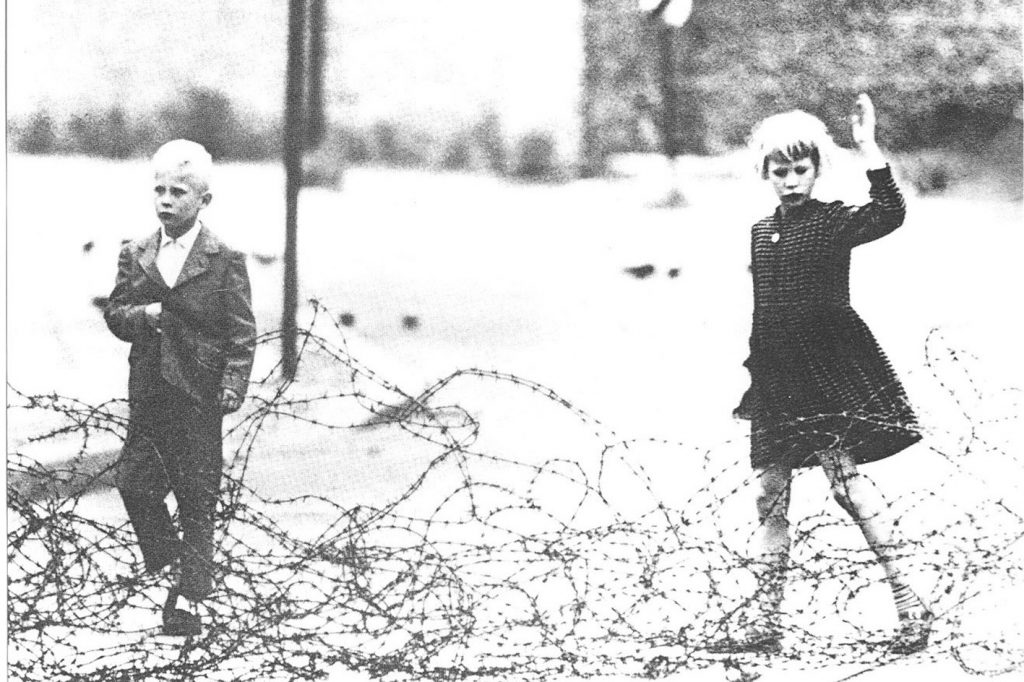

(Fermo immagine dal film di Dino Risi I mostri, 1963, unanimemente considerato una critica corrosiva delle certezze dell’Italia del boom economico.)

Ancora, alla fine di tutte queste divagazioni, non ho risolto il problema iniziale: quando e come i ”fenomeni morbosi” sono divenuti ”mostri” e ”l’interregno” un ”chiaroscuro”?

Ho trovato su Internet qualche vecchia cartolina, una francese non datata (ma dalla grafica piuttosto ”anni Settanta”, un’americana del 1982.

.

Ho trovato anche una maglietta disponibile in nove colori diversi:

.

.

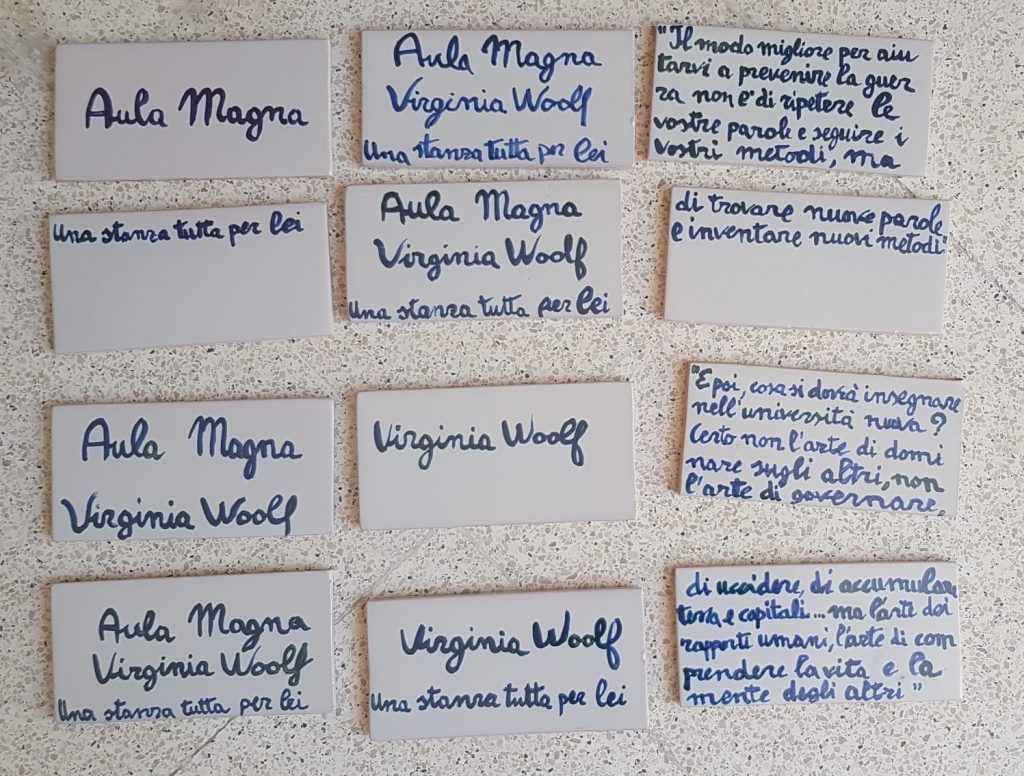

Circolo Arci ”Il cosmonauta”, Viterbo, maggio 2022

Circolo Arci ”Il cosmonauta”, Viterbo, maggio 2022

.

Infine, una nota positiva: la citazione di Gramsci, nella sua versione ”poetica”, è ancora e sempre d’attualità. I mostri, a forza di essere evocati, non fanno più tanta paura e possono ritrovarsi in un annuncio commerciale postato su Linkedin, a fine 2022:

‘’Créer des Mondes meilleurs avec et pour nos clients!”

.

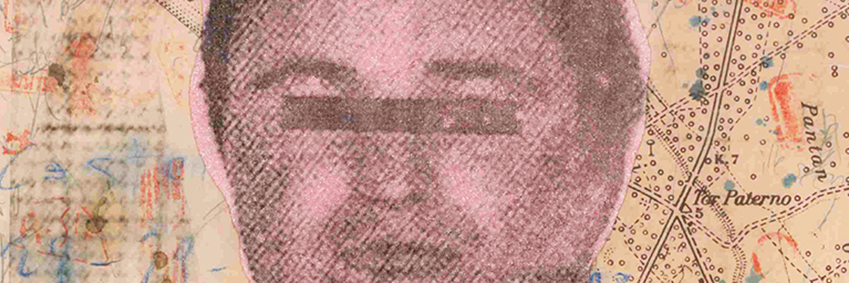

Concludo riproducendo la foto segnaletica di Antonio Gramsci eseguita il 29 gennaio 1935 e consultabile presso l’Archivio Centrale di Stato (Casellario Politico Centrale). Non è la stessa delle magliette alla ”Che Guevara” ma è lo stesso una bella foto.

Antonio Sebastiano Francesco Gramsci (Ales, 22 gennaio 1891 – Roma, 27 aprile 1937).

Antonio Sebastiano Francesco Gramsci (Ales, 22 gennaio 1891 – Roma, 27 aprile 1937).

.

Nota. Mi permetto di rimandare ad alcuni lavori personali su questa tematica:

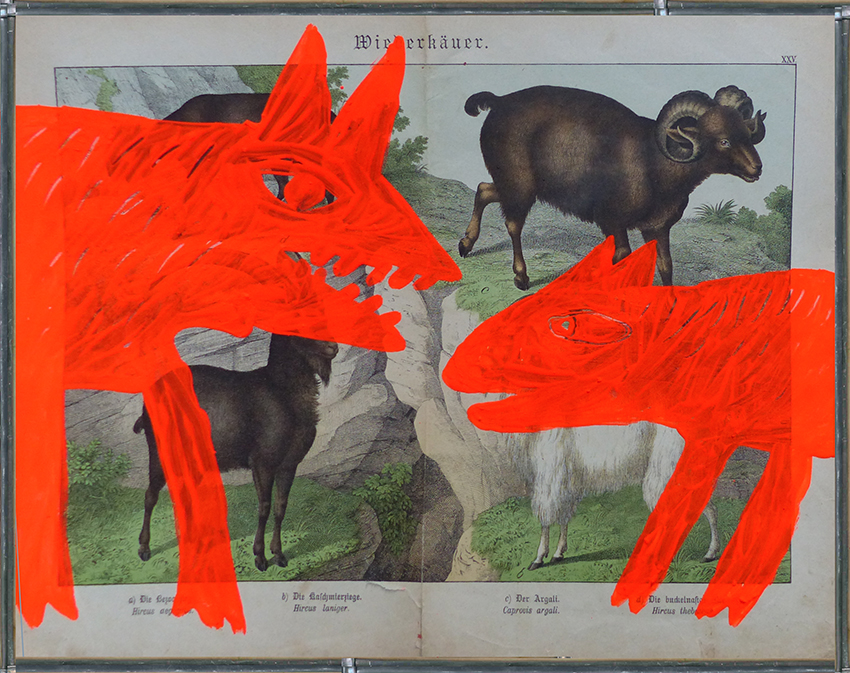

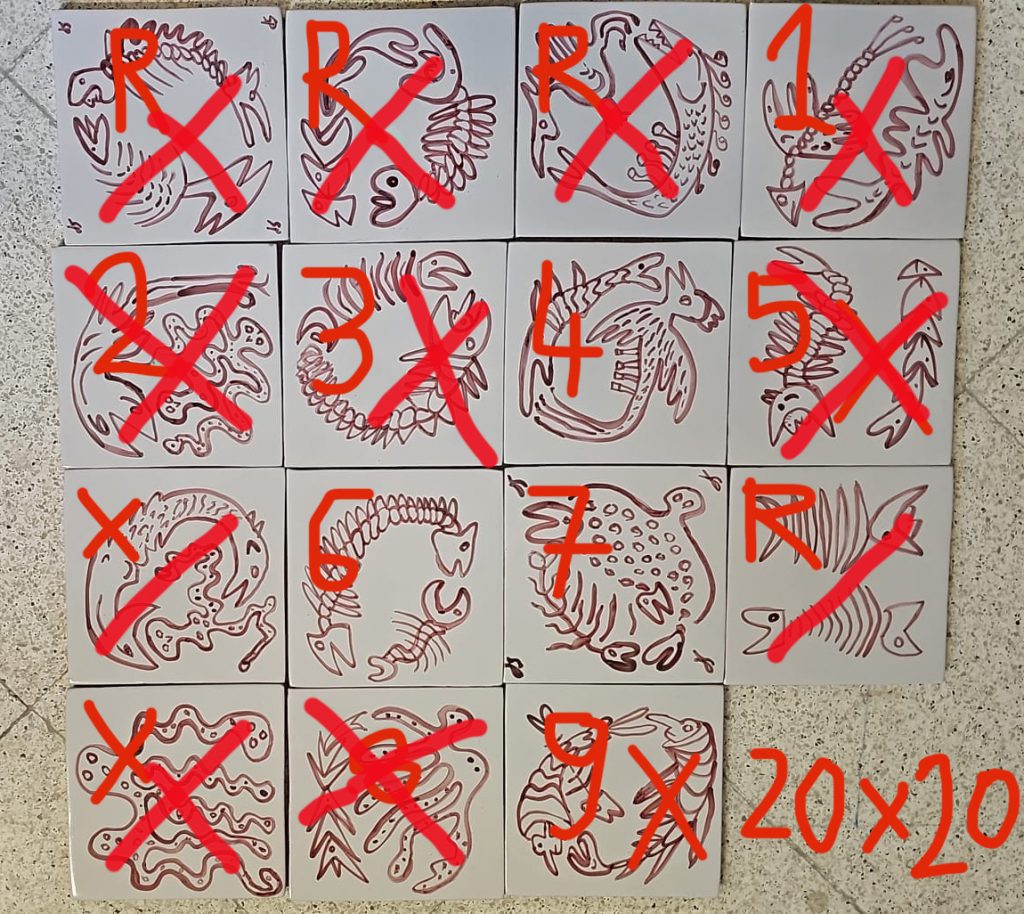

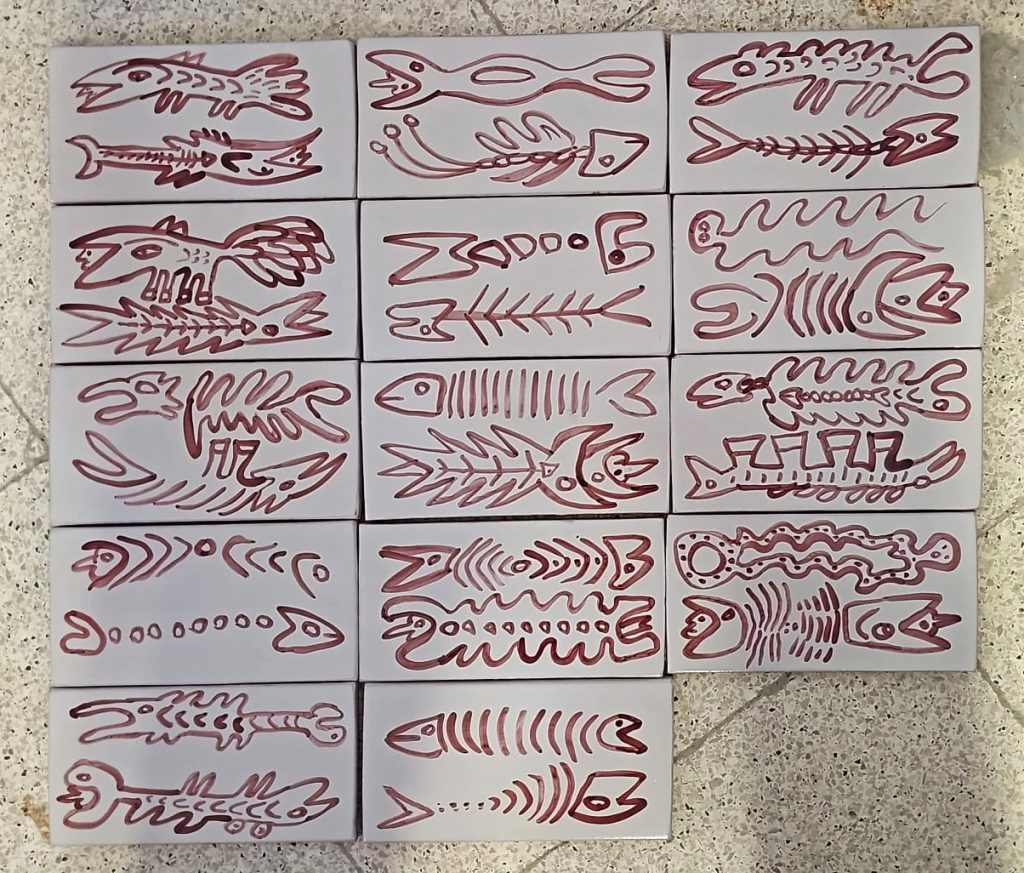

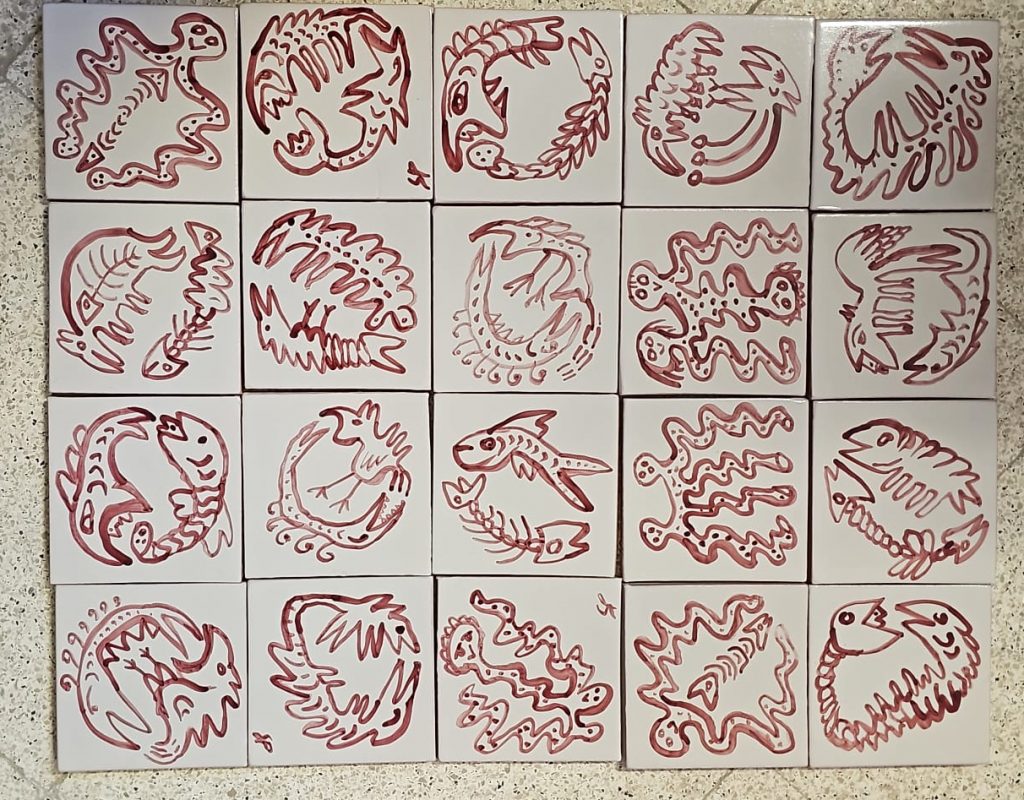

Bestiaire, 2023

Histoire des monstres bis, 2023

Nuovi mostri, 2023

Birds of Lent, 2022

Histoire des monstres, 2021-2022

Disegni di quaresima, 2020

Le jardin des monstres, 2014

Infine, il risultato di questo lavoro di preparazione sarà un trittico, il quinto di una recente serie sugli anni Settanta:

Fenomeni morbosi svariati

Luglio 2024: la serie dei 104 Pulcianelli essendo compiuta, mi accingo a sviluppare un nuovo soggetto di scottante attualità: le anime del Purgatorio. Già nel 1987 mi ero interessato all’argomento ma in forma differente: il risultato ne era stato un breve testo pubblicato sul numero 33, 1988, della rivista Linea d’ombra (vedi link).

Luglio 2024: la serie dei 104 Pulcianelli essendo compiuta, mi accingo a sviluppare un nuovo soggetto di scottante attualità: le anime del Purgatorio. Già nel 1987 mi ero interessato all’argomento ma in forma differente: il risultato ne era stato un breve testo pubblicato sul numero 33, 1988, della rivista Linea d’ombra (vedi link).

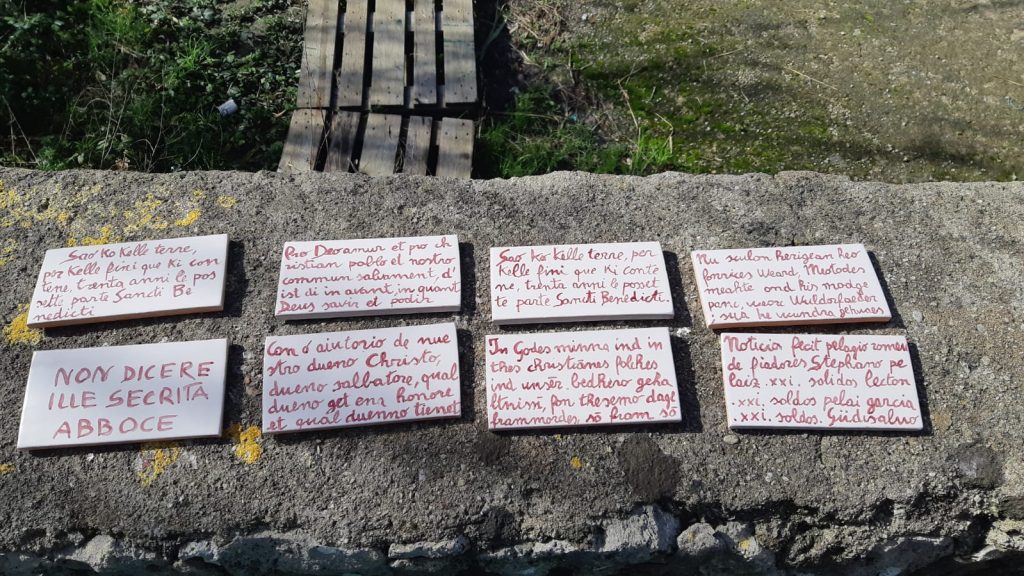

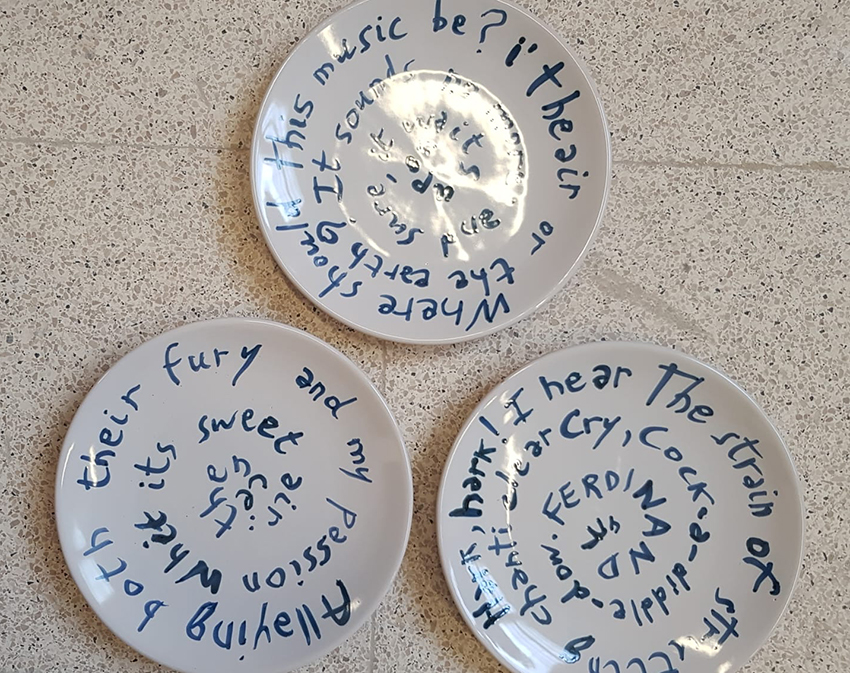

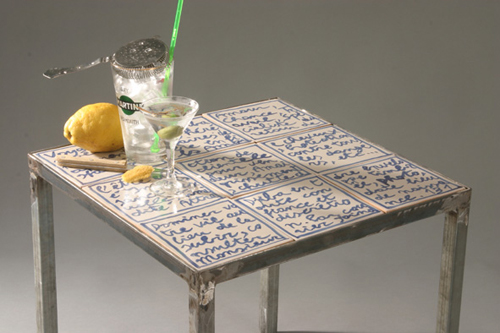

Plat de Carême

Plat de Carême Sushi 13×26

Sushi 13×26

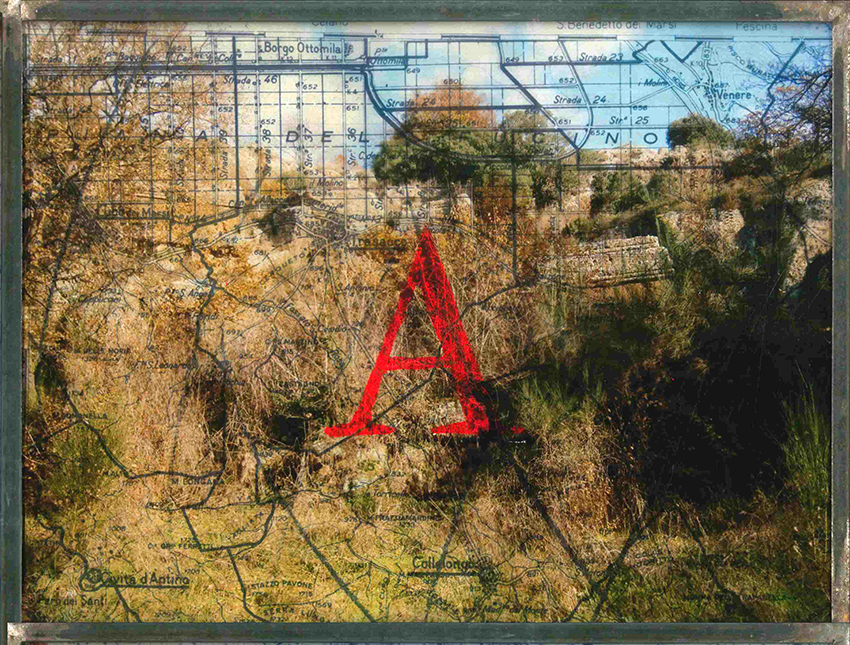

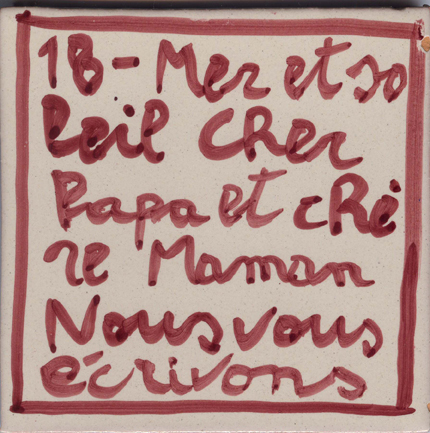

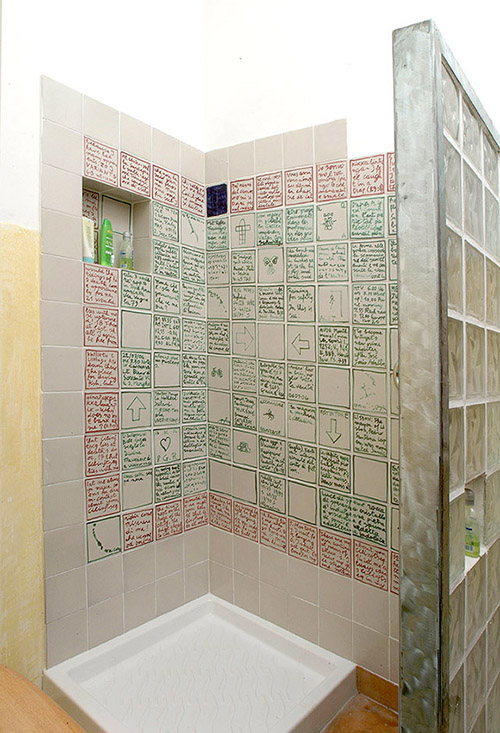

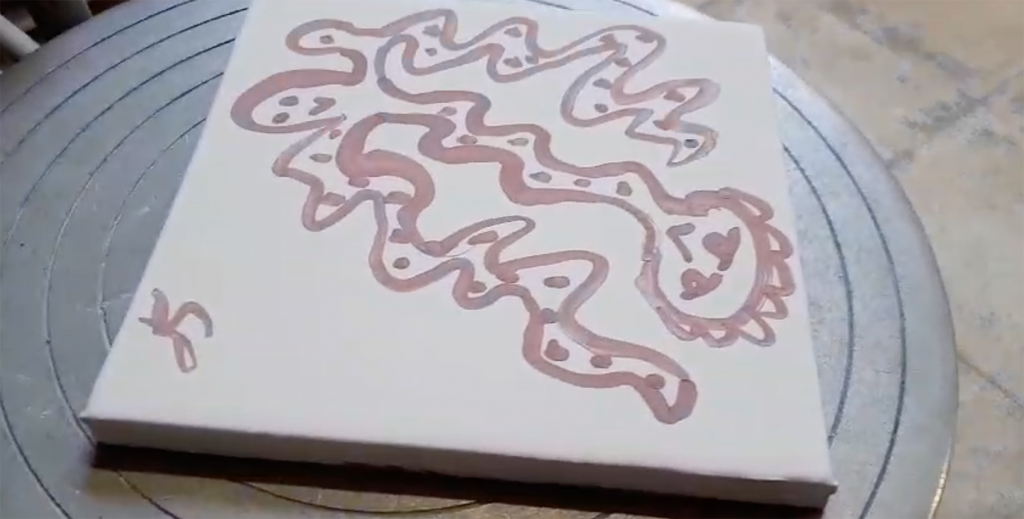

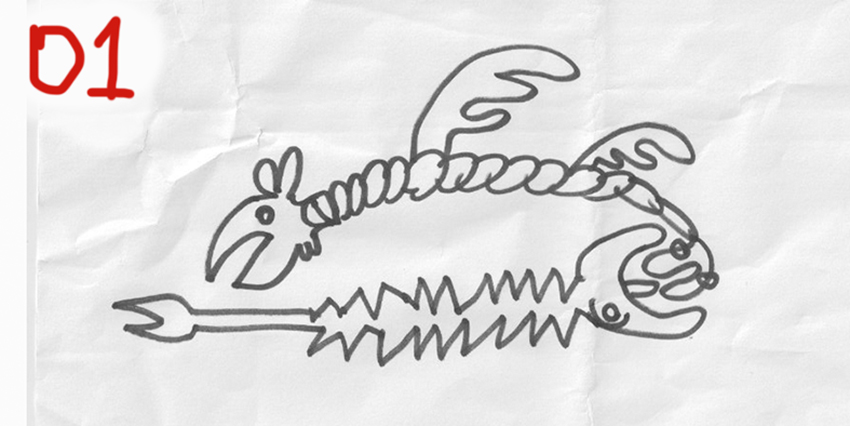

Histoire des monstres 00, Poggio Rota, 30×30, completed December 13.

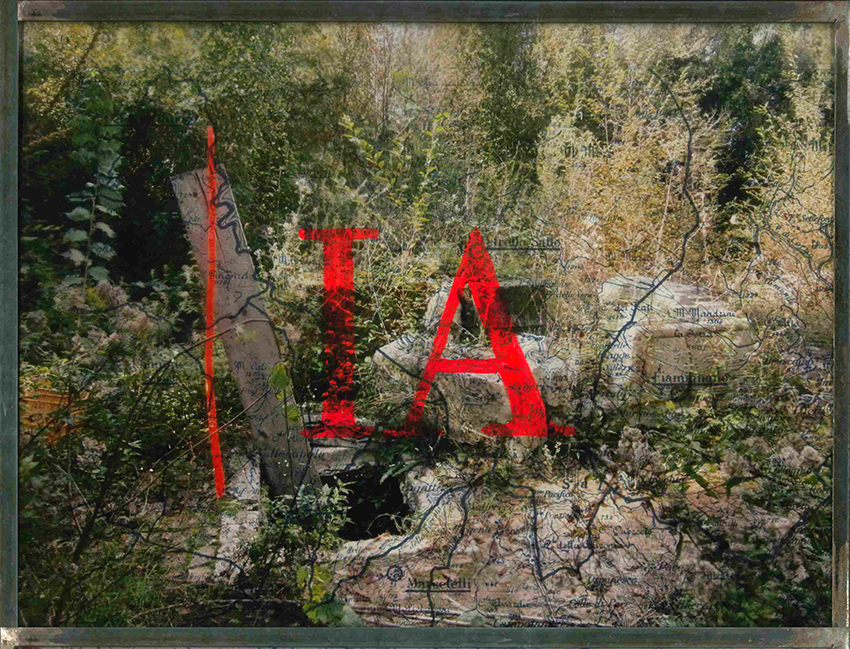

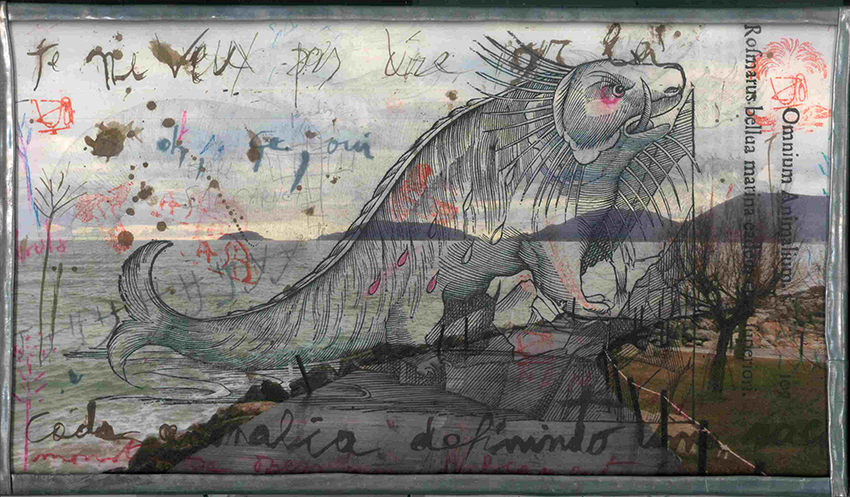

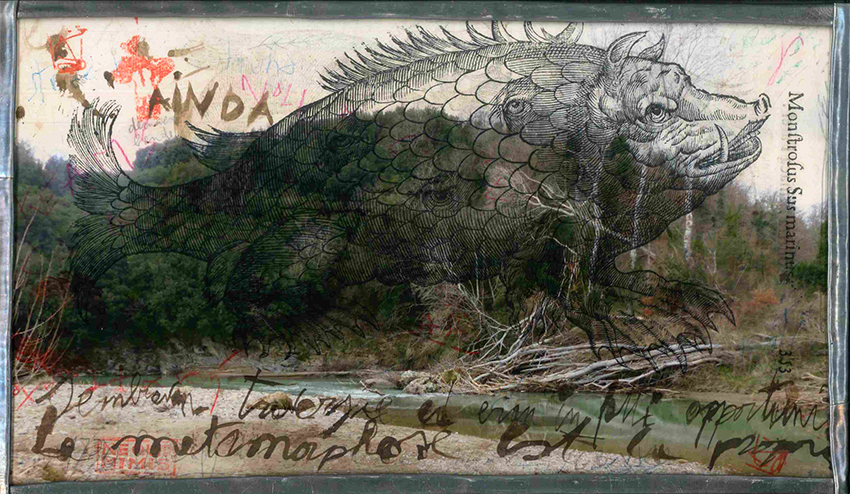

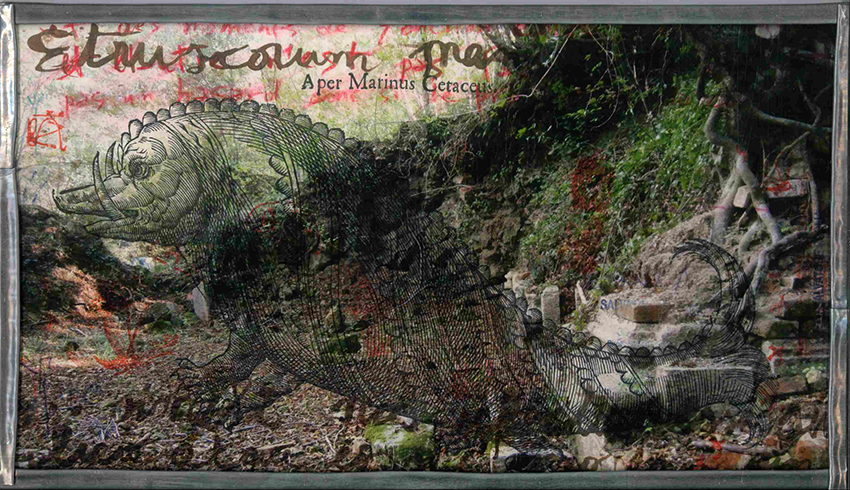

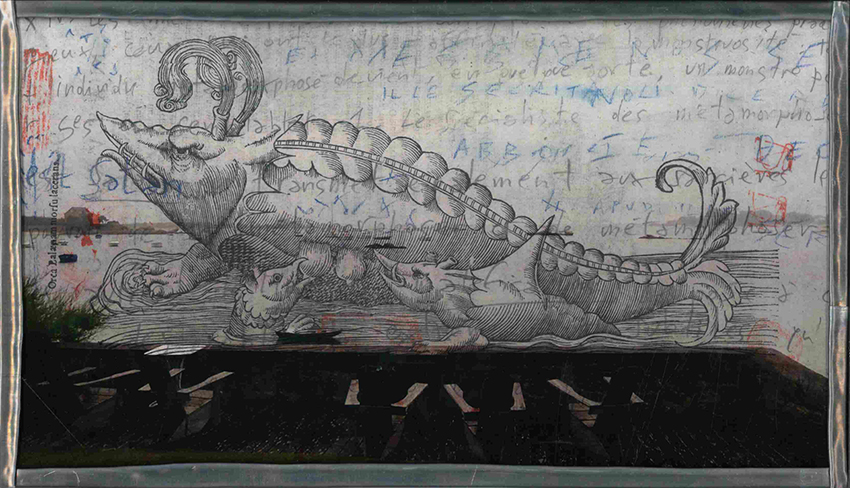

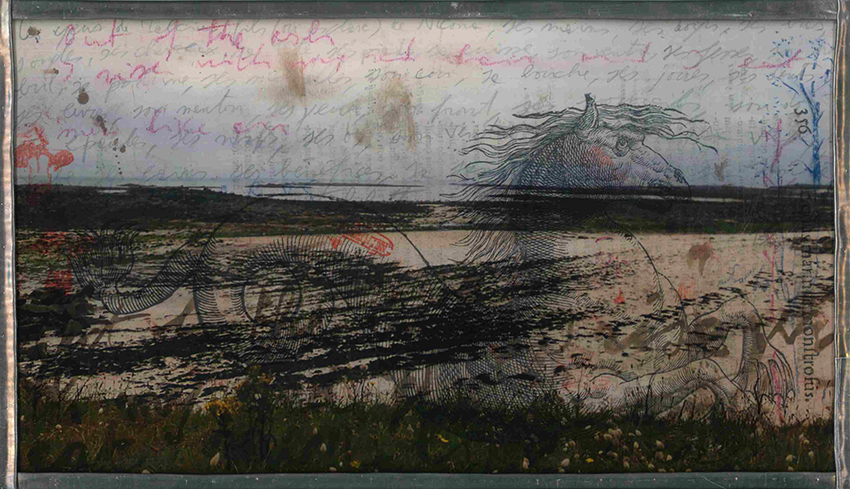

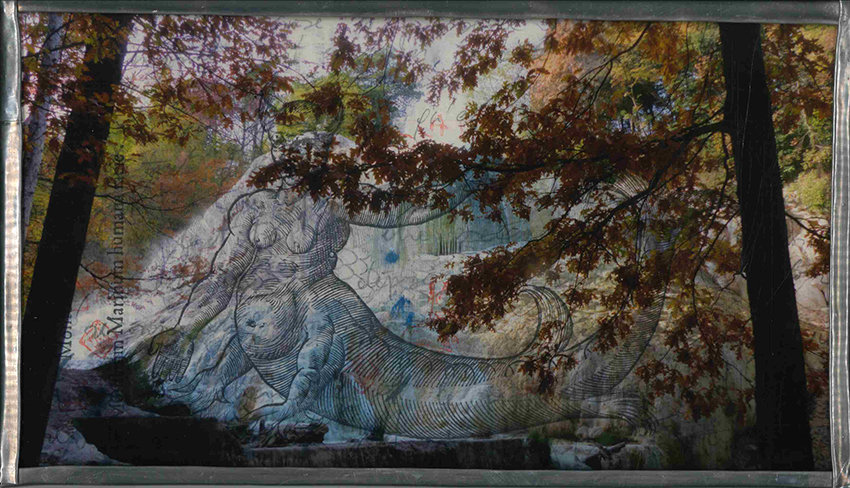

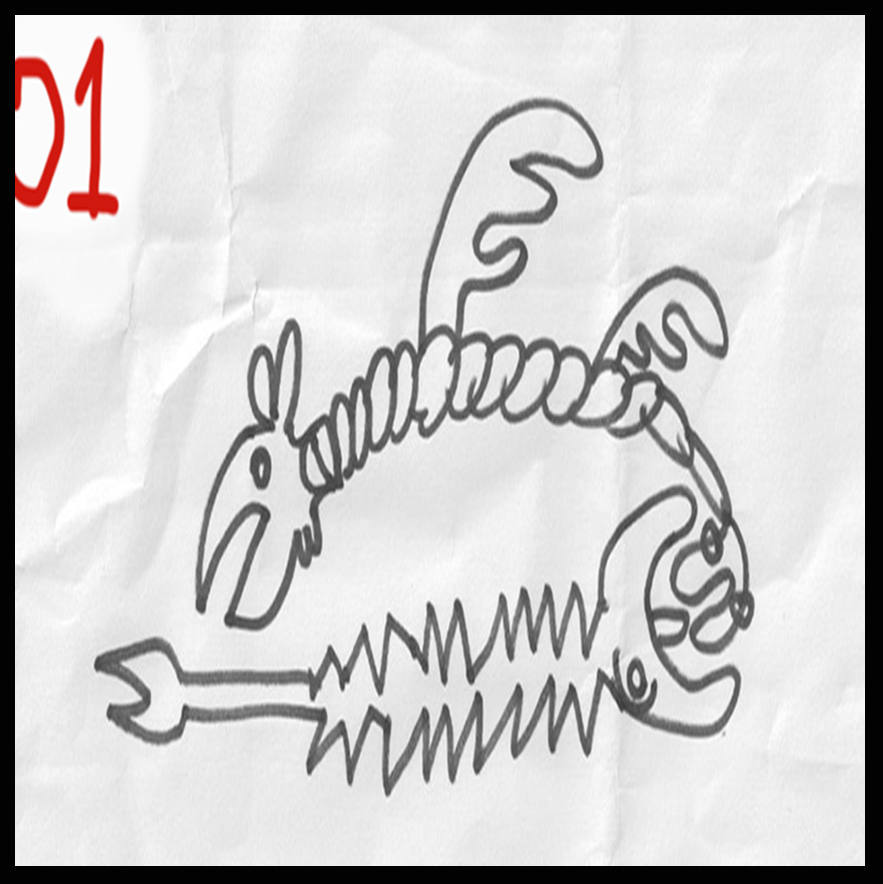

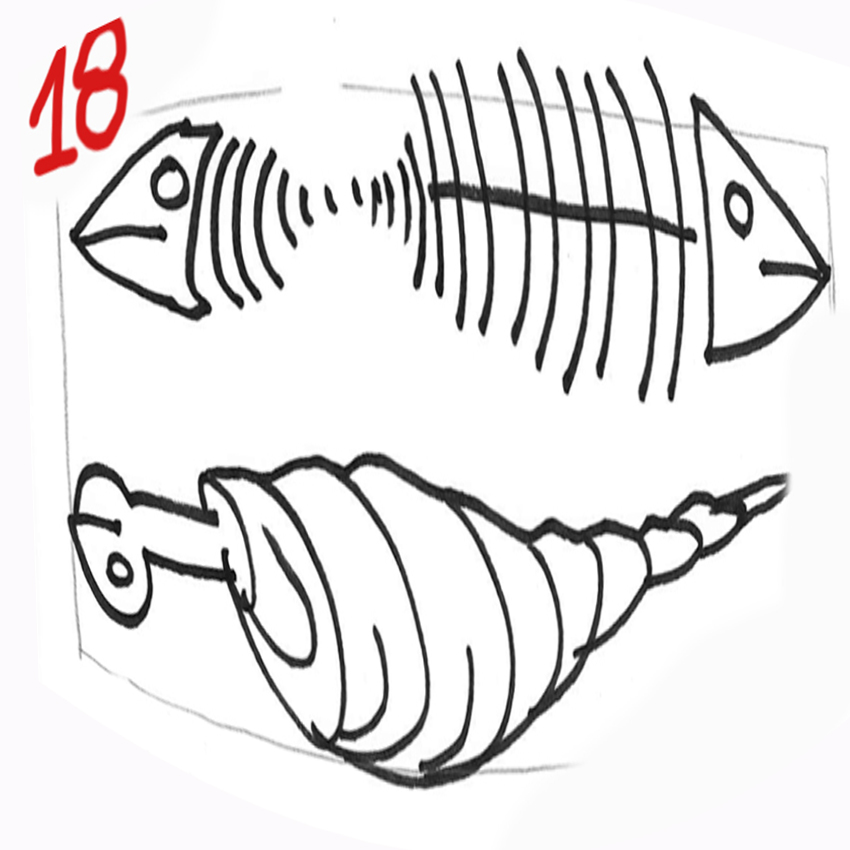

Histoire des monstres 00, Poggio Rota, 30×30, completed December 13. Histoire des monstres 01, Fiora, 24×42, completed December 15.

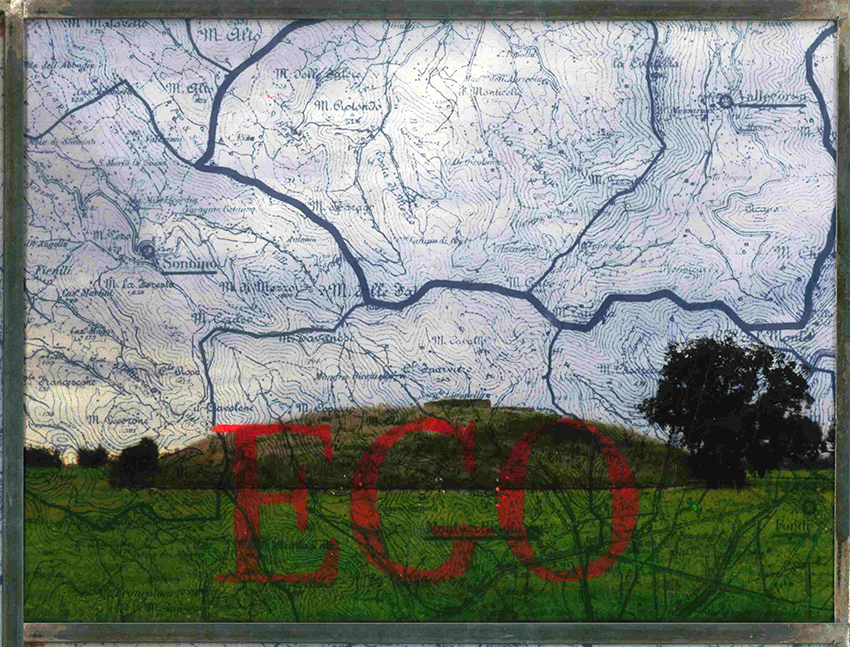

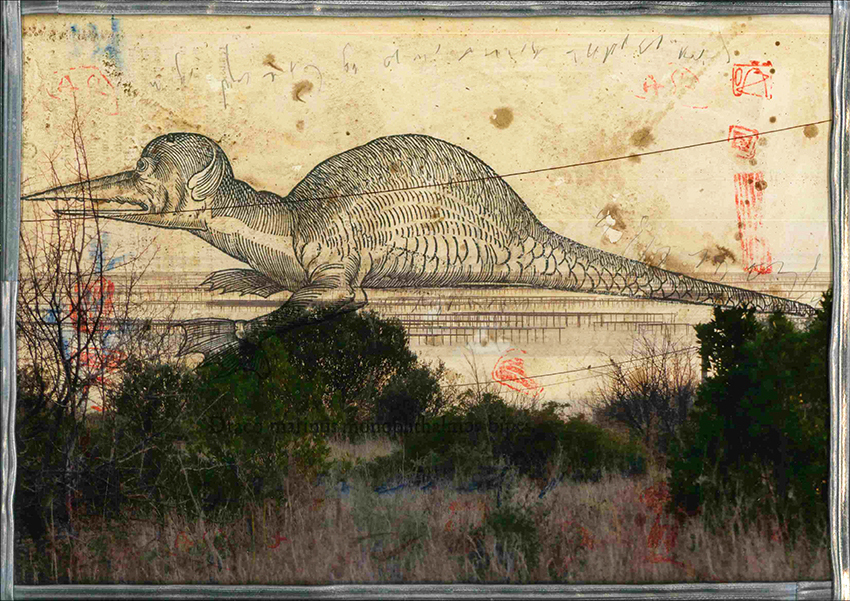

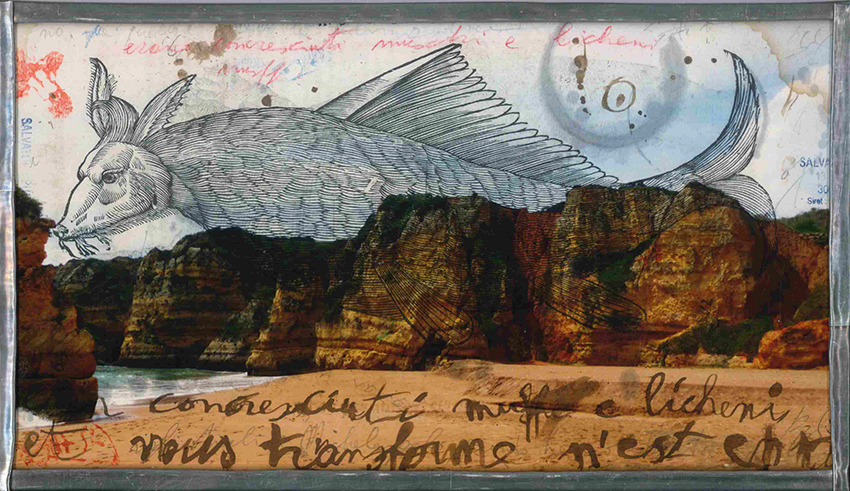

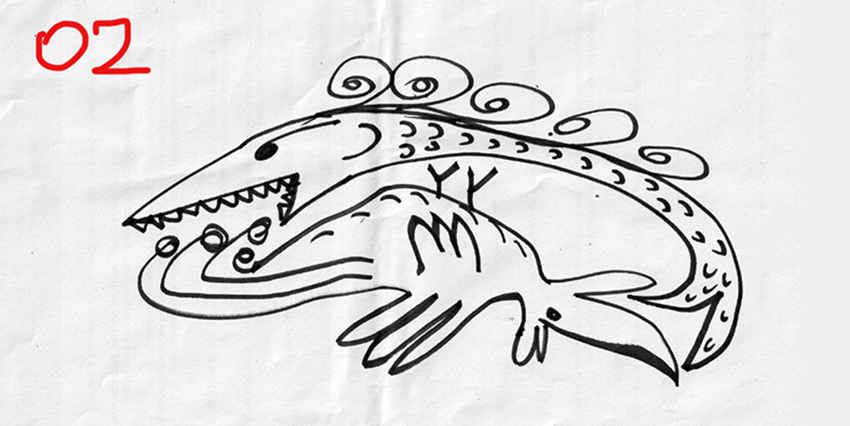

Histoire des monstres 01, Fiora, 24×42, completed December 15. Histoire des monstres 02, Lagos, 24×42, completed December 16.

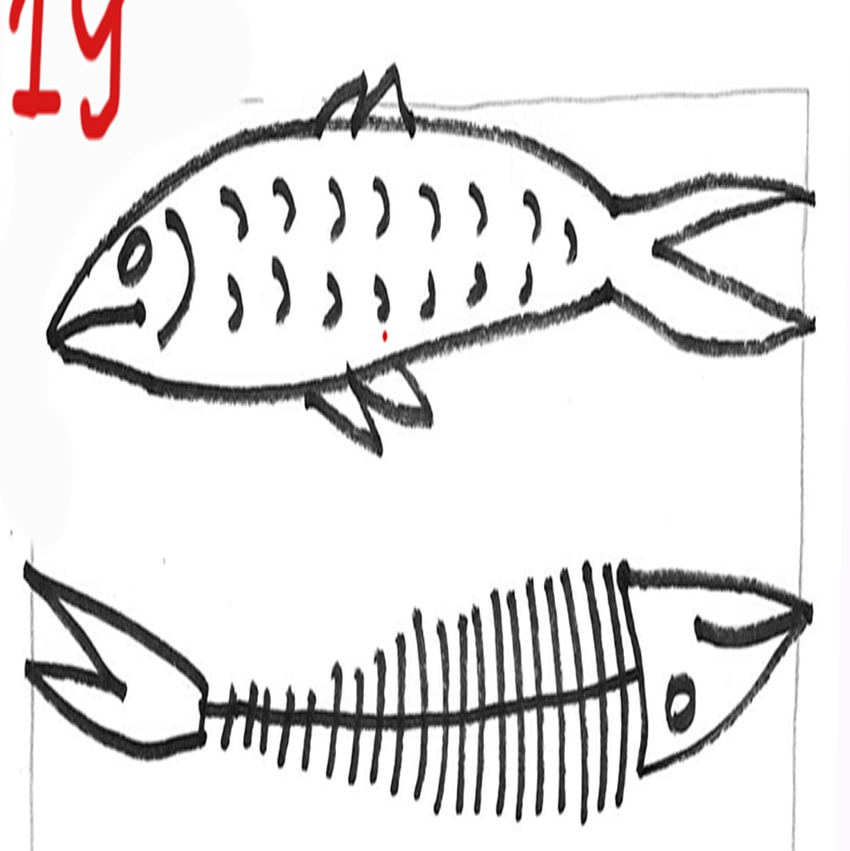

Histoire des monstres 02, Lagos, 24×42, completed December 16. Histoire des monstres 03, Rofalco, 24×42, completed December 17.

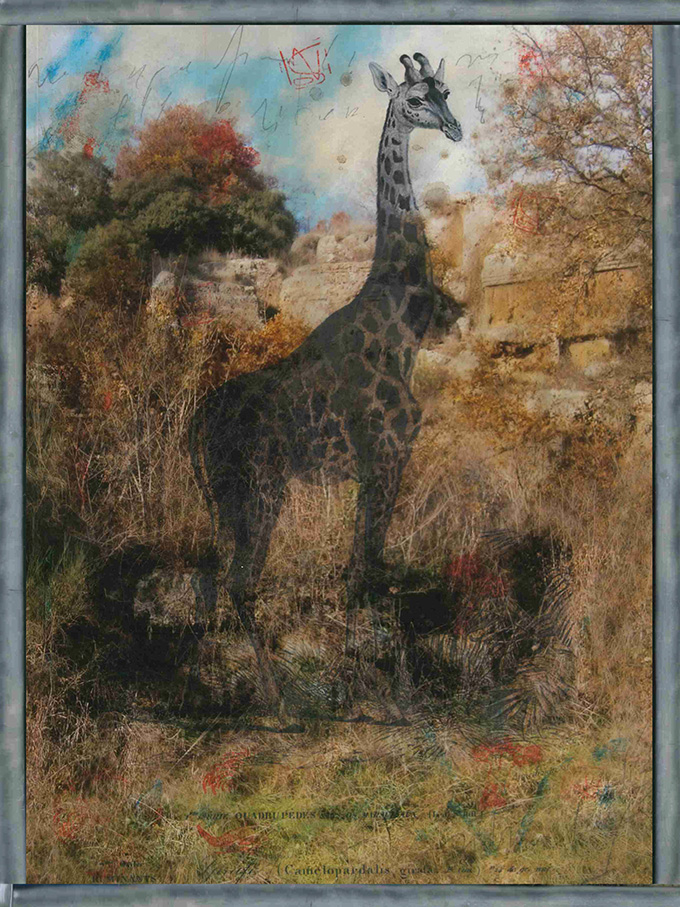

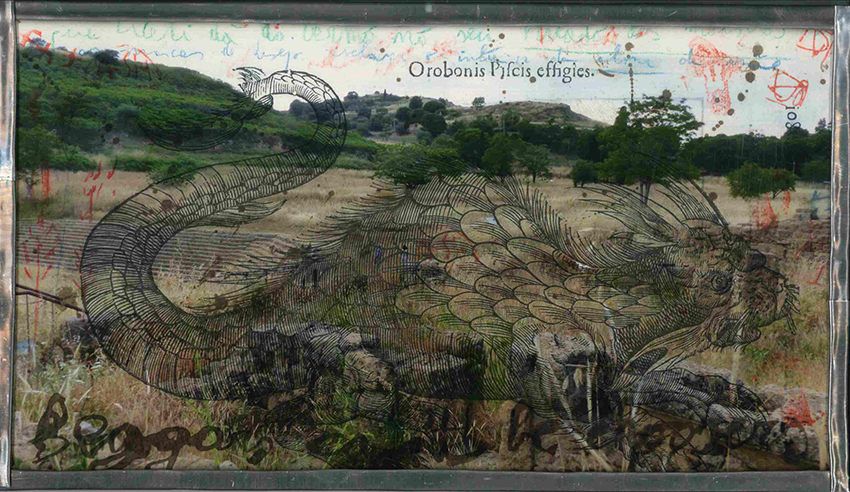

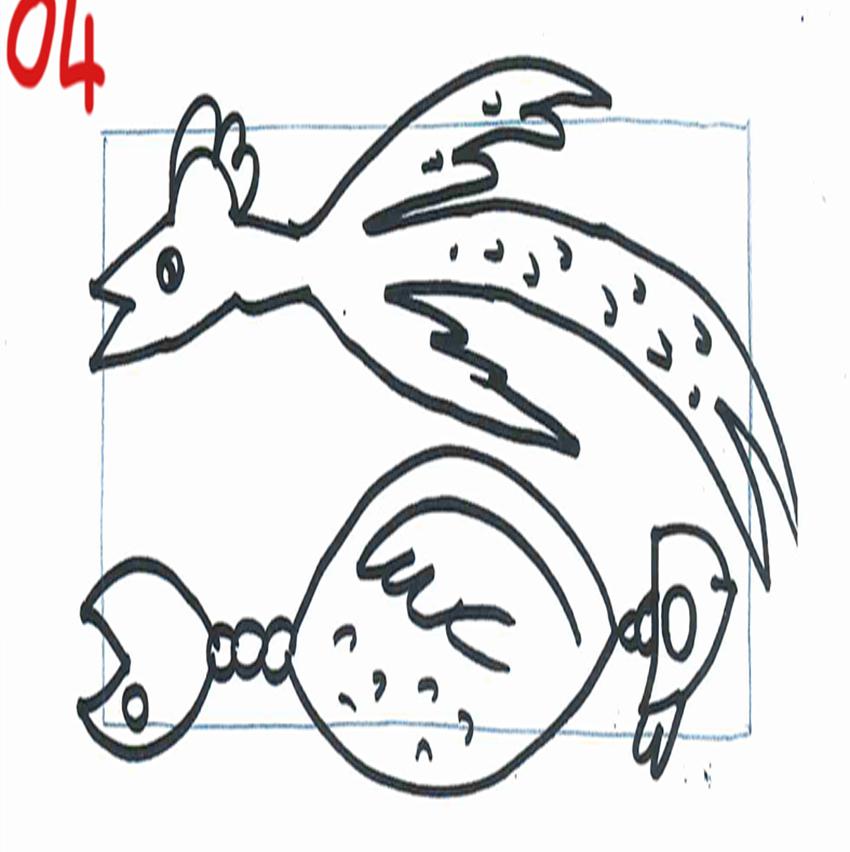

Histoire des monstres 03, Rofalco, 24×42, completed December 17. Histoire des monstres 04, Morgantina, 24×42, completed Decembre 19.

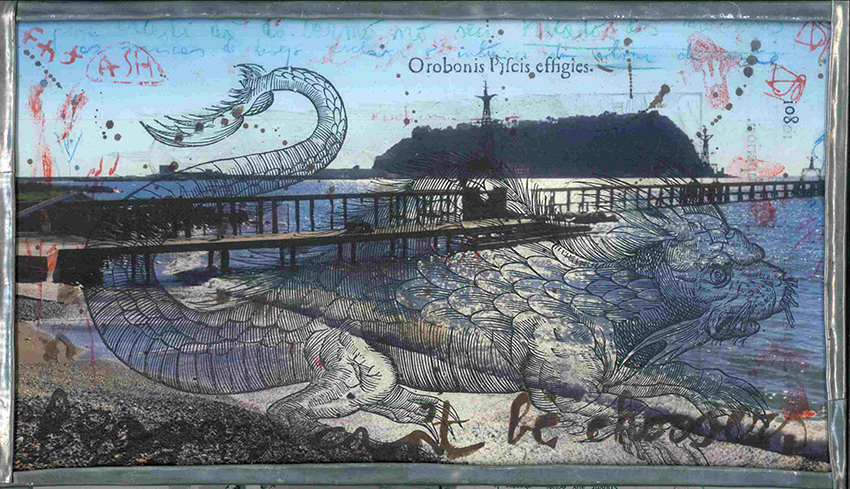

Histoire des monstres 04, Morgantina, 24×42, completed Decembre 19. Histoire des monstres 05, Castro, 24×42, completed December 20.

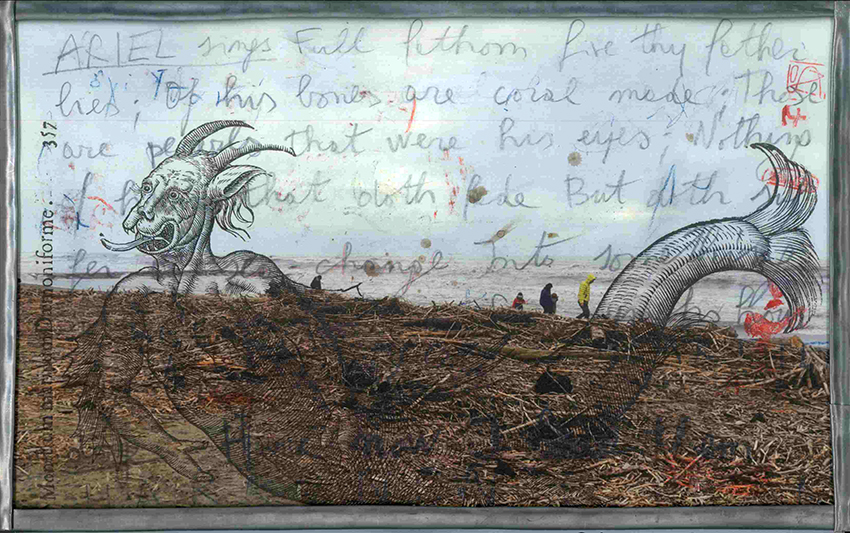

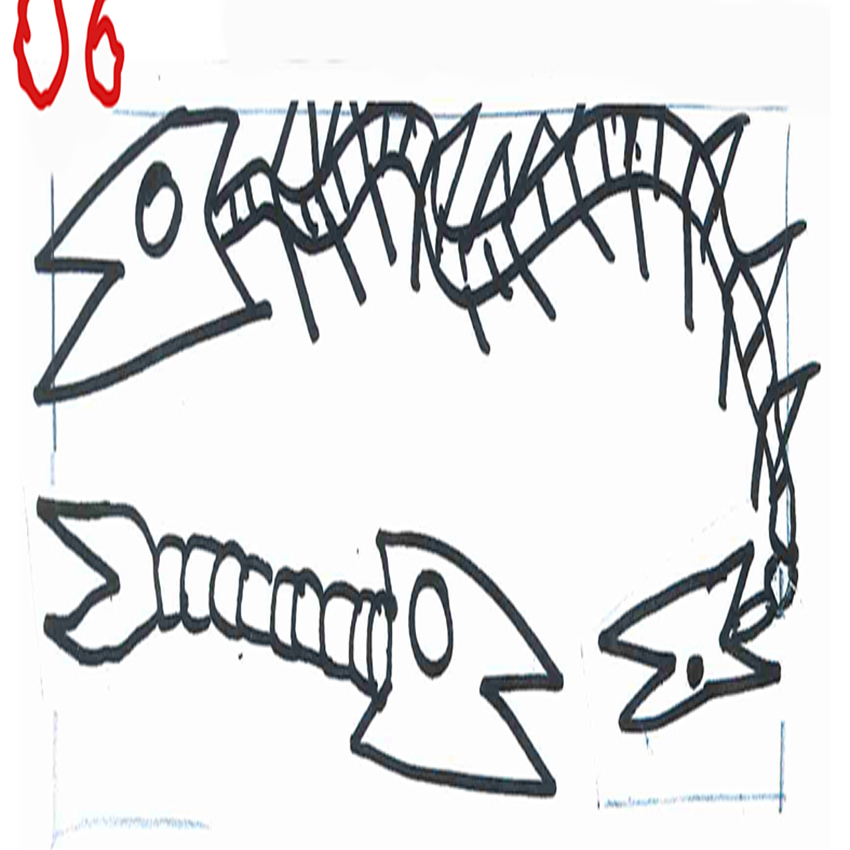

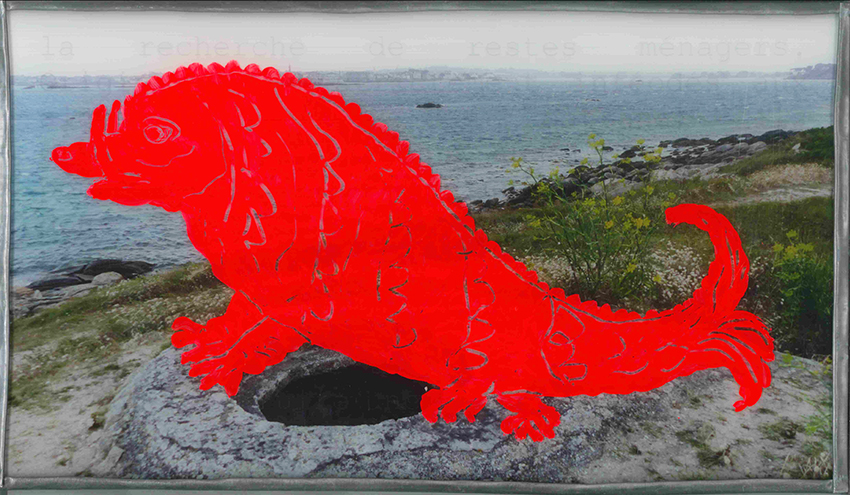

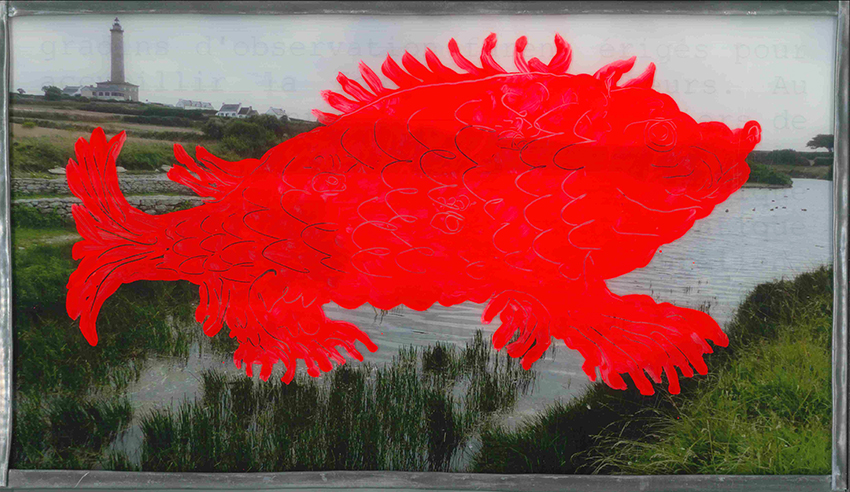

Histoire des monstres 05, Castro, 24×42, completed December 20. Histoire des monstres 06, Brignogan-Plage, 24×42, completed December 22.

Histoire des monstres 06, Brignogan-Plage, 24×42, completed December 22. Histoire des monstres 07, Fratenuti, 24×42, completed December 24.

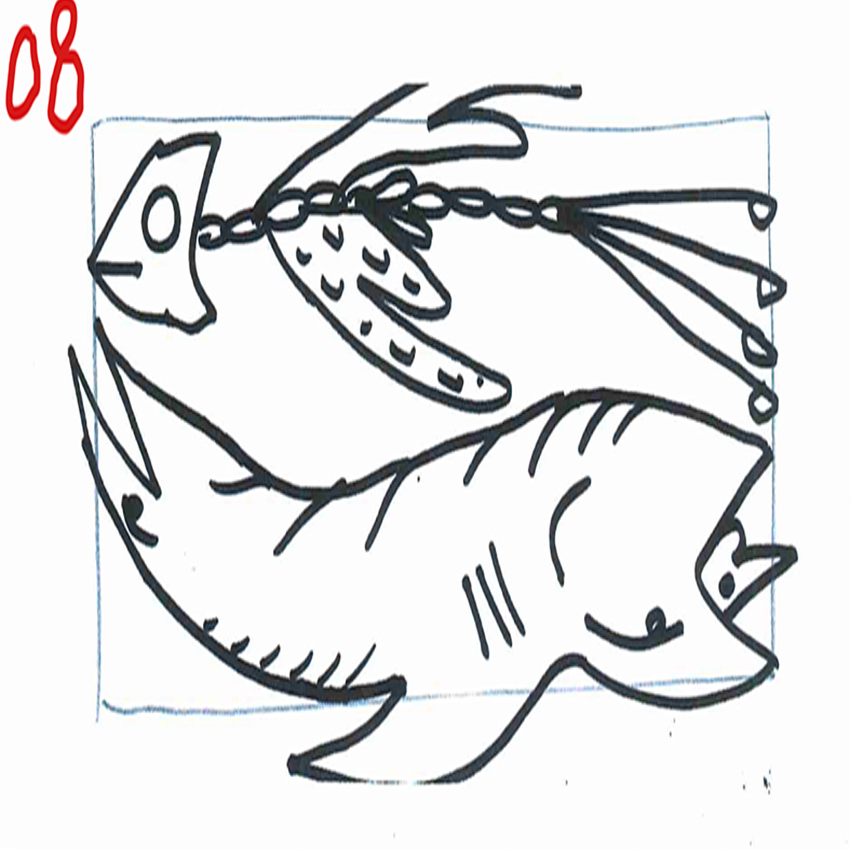

Histoire des monstres 07, Fratenuti, 24×42, completed December 24. Histoire des monstres 08, Batz, 24×42, completed December 25.

Histoire des monstres 08, Batz, 24×42, completed December 25. Histoire des monstres 09, Fosso bianco, 24×42, completed December 26.

Histoire des monstres 09, Fosso bianco, 24×42, completed December 26. Histoire des monstres 10, Balena bianca, 24×42, completed December 27.

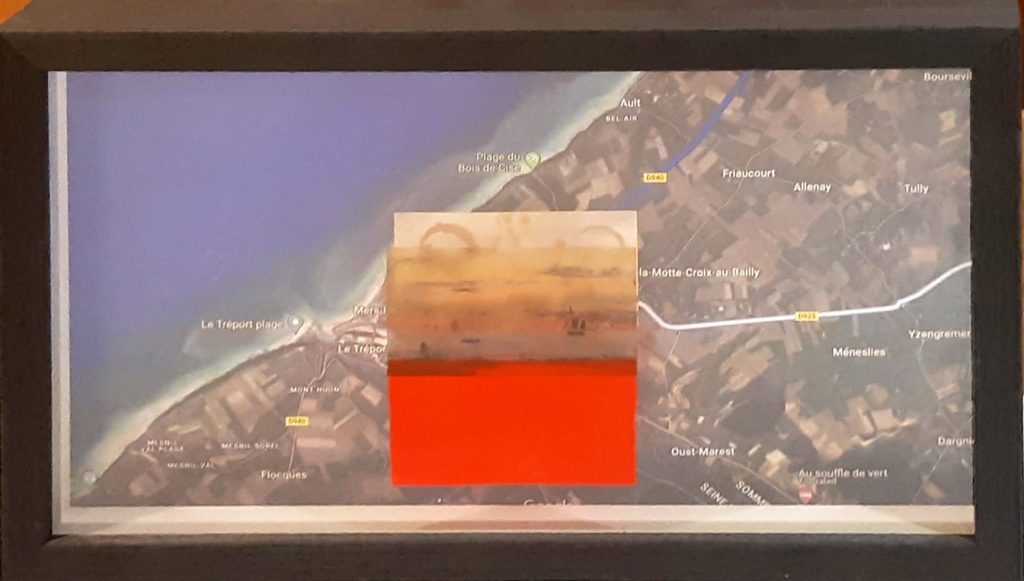

Histoire des monstres 10, Balena bianca, 24×42, completed December 27. Histoire des monstres 11, Camp de César, 24×42, completed December 28.

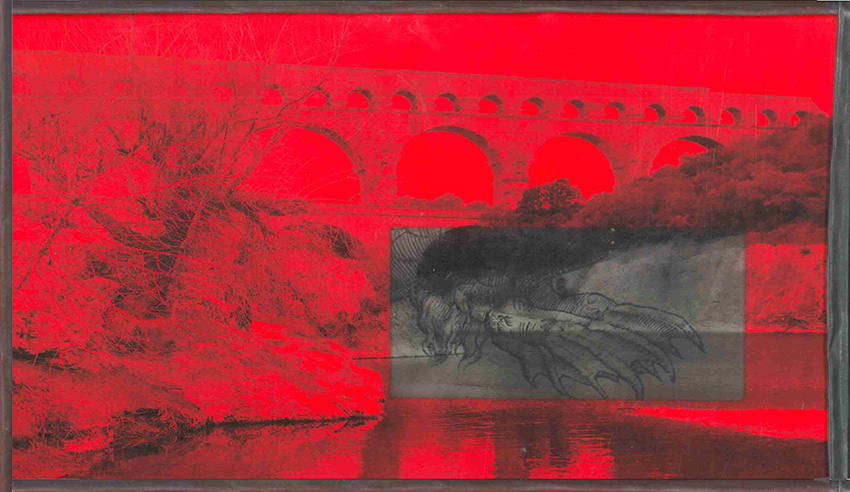

Histoire des monstres 11, Camp de César, 24×42, completed December 28. Histoire des monstres 12, Ponte san Pietro, 24×42, completed December 29.

Histoire des monstres 12, Ponte san Pietro, 24×42, completed December 29. .

.

Histoire des monstres 07 bis, Via cava Fratenuti-Raia exiccata, 24×42.

Histoire des monstres 07 bis, Via cava Fratenuti-Raia exiccata, 24×42.

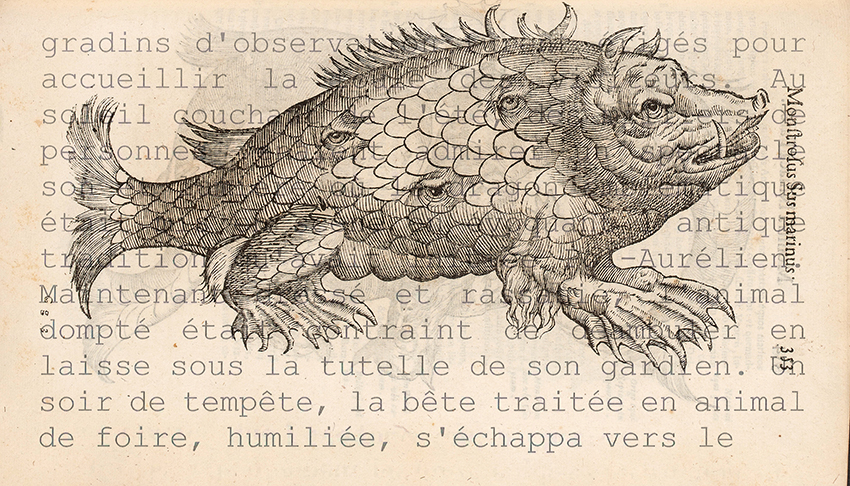

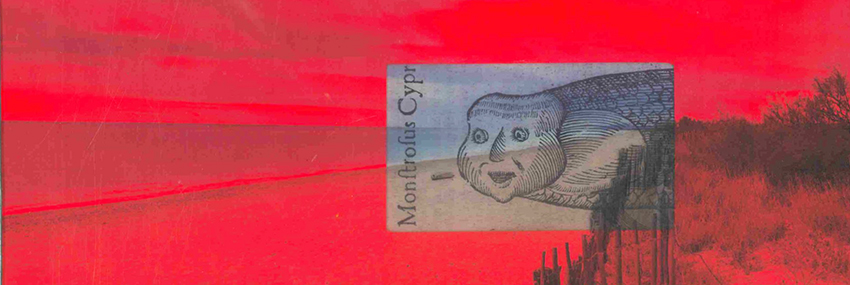

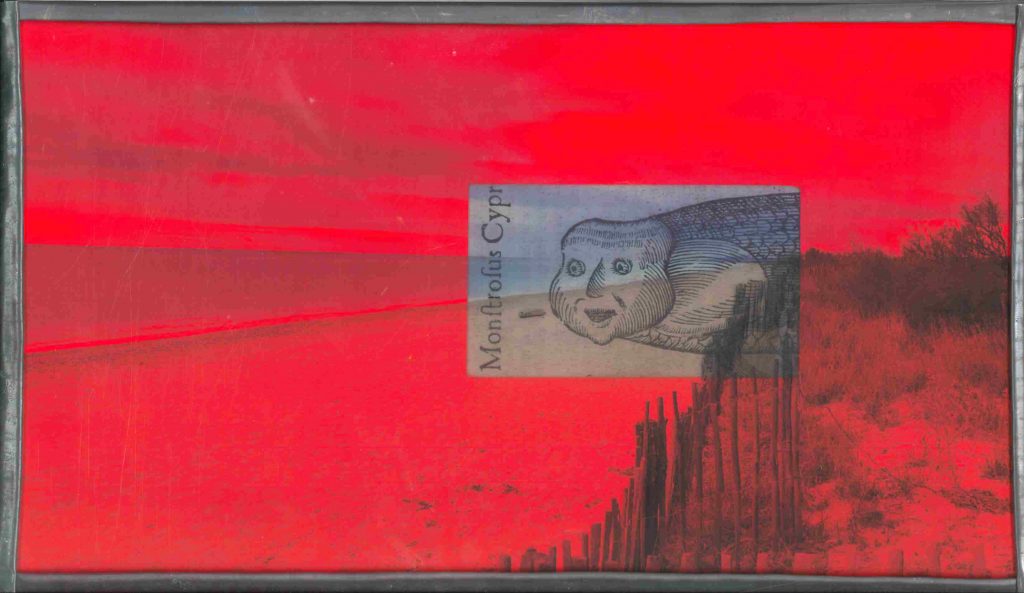

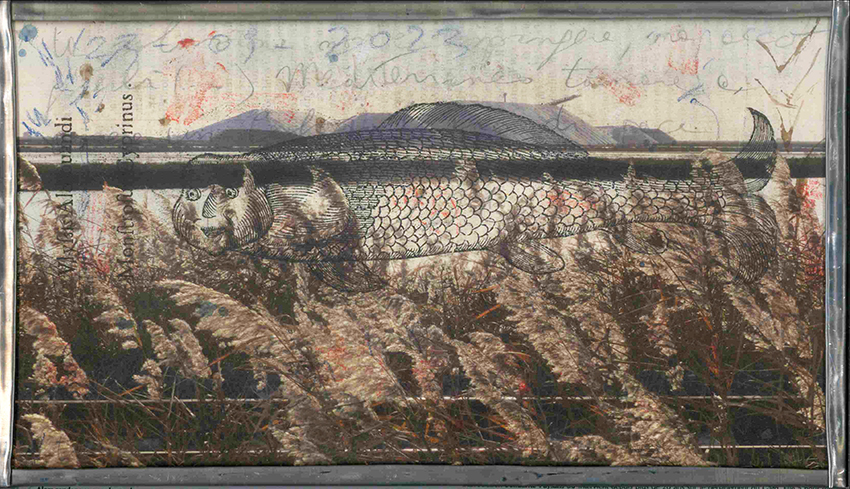

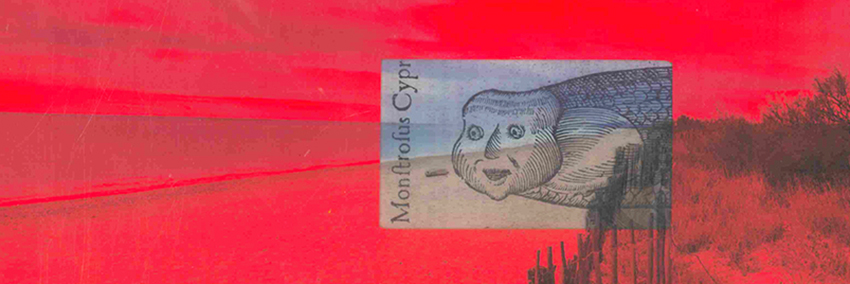

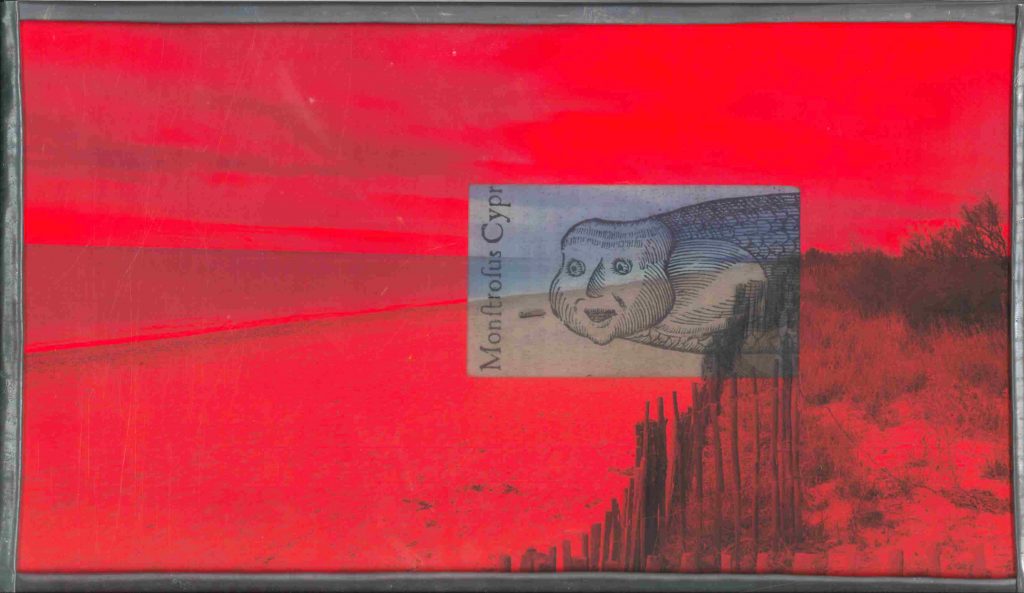

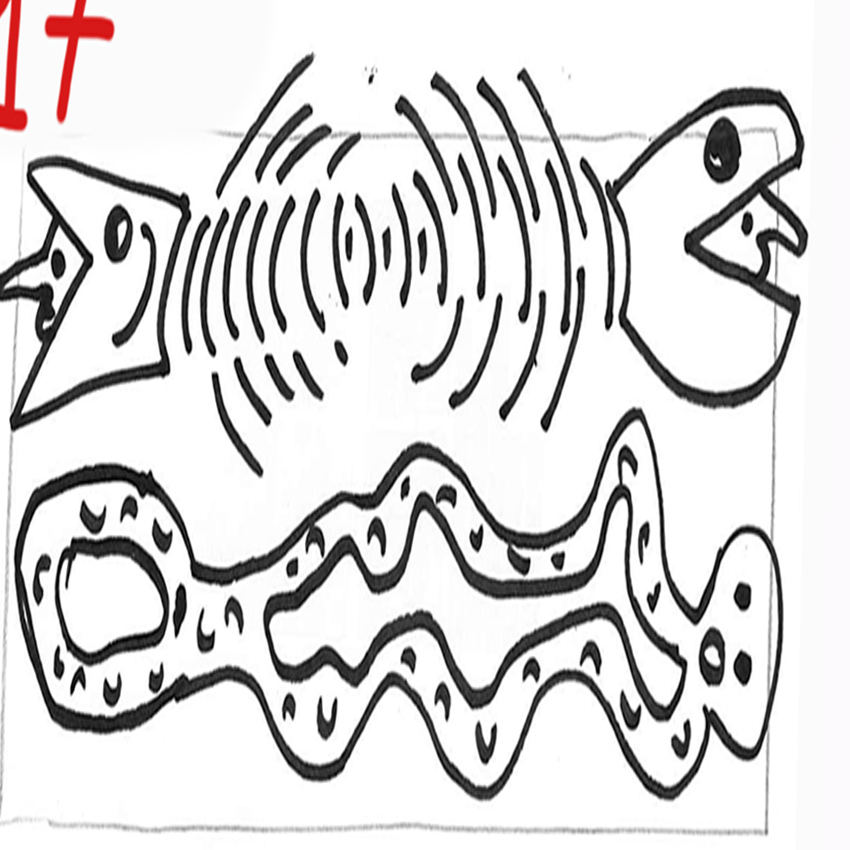

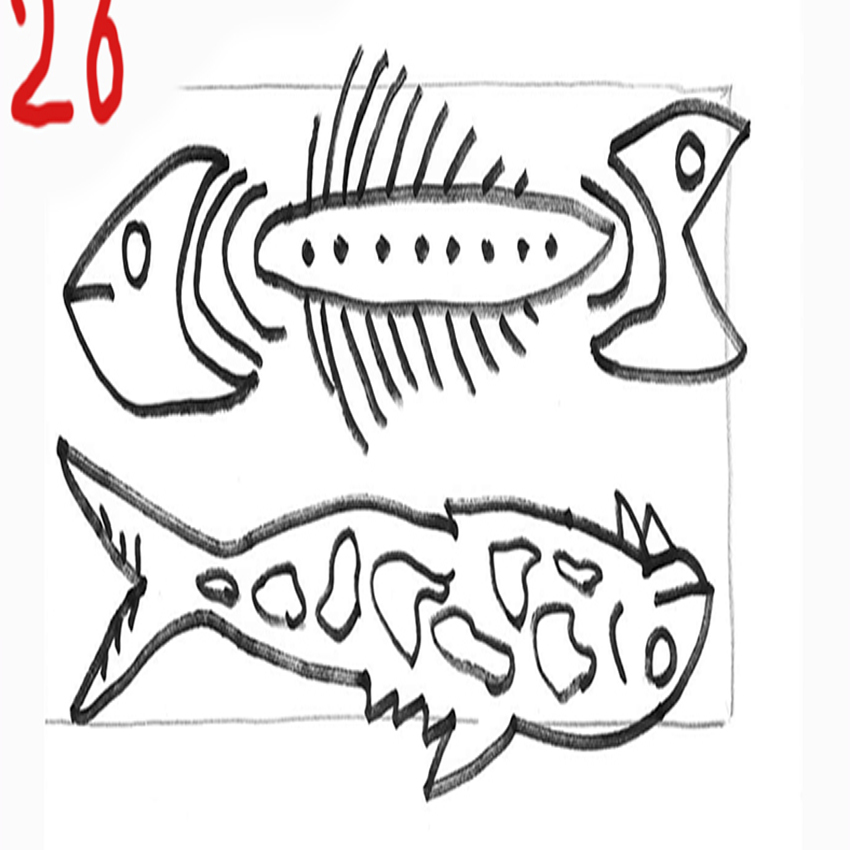

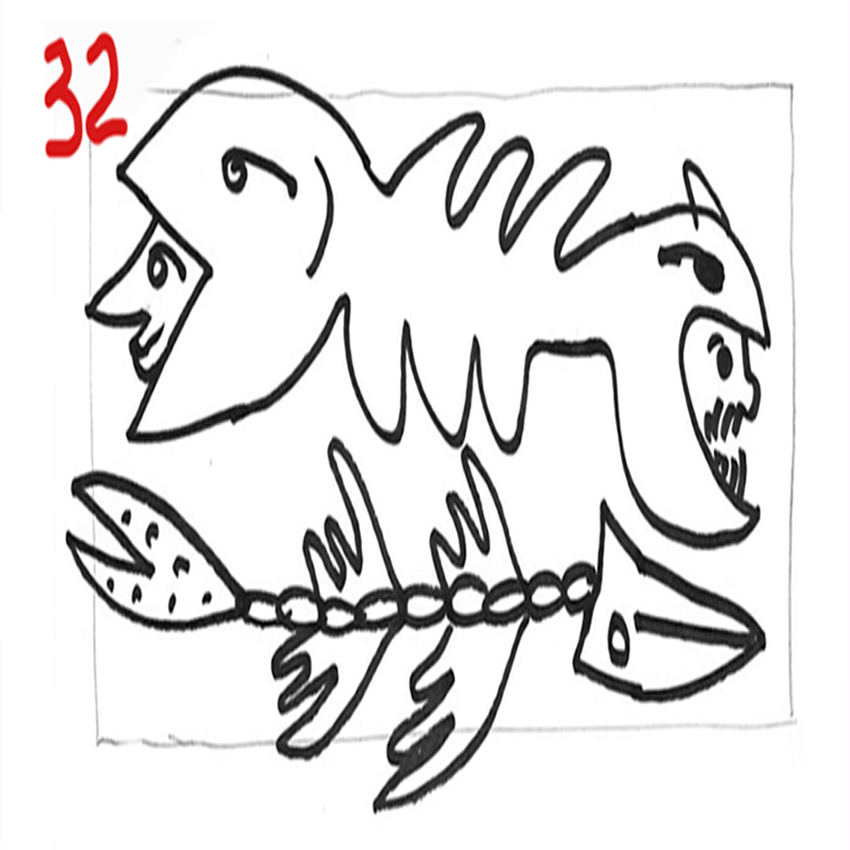

Histoire des monstres 16 bis , Maguelone-Monstrosus Cyprinus, 24×42.

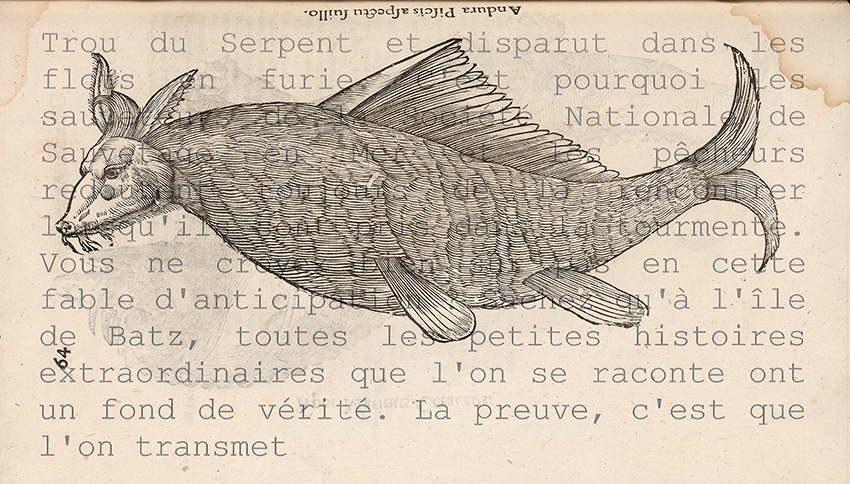

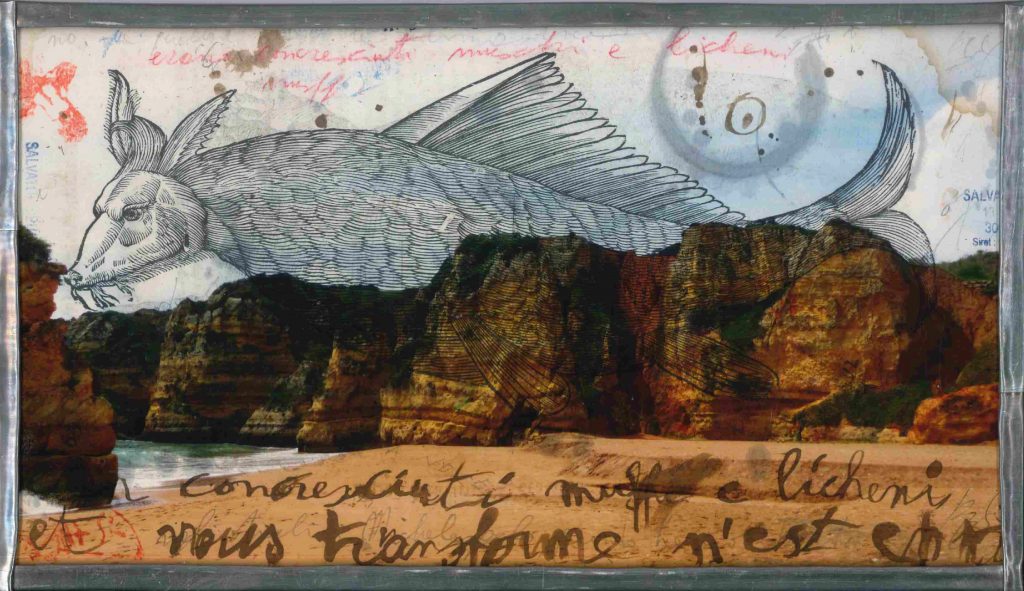

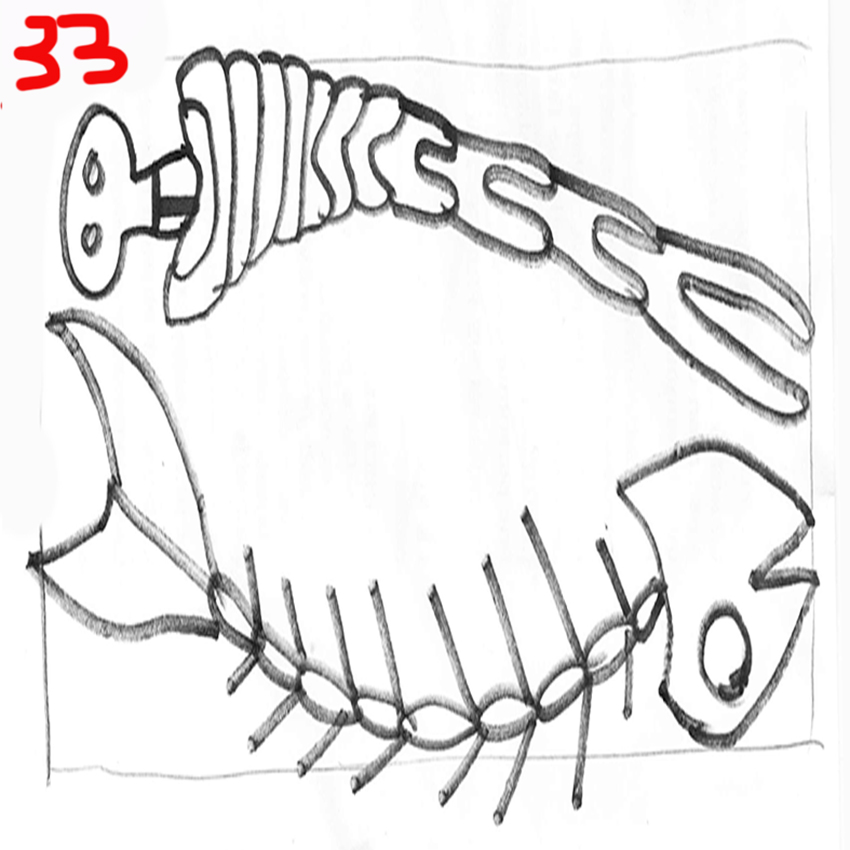

Histoire des monstres 16 bis , Maguelone-Monstrosus Cyprinus, 24×42. Histoire des monstres 02 bis, Lagos-Andura piscis, 24×42.

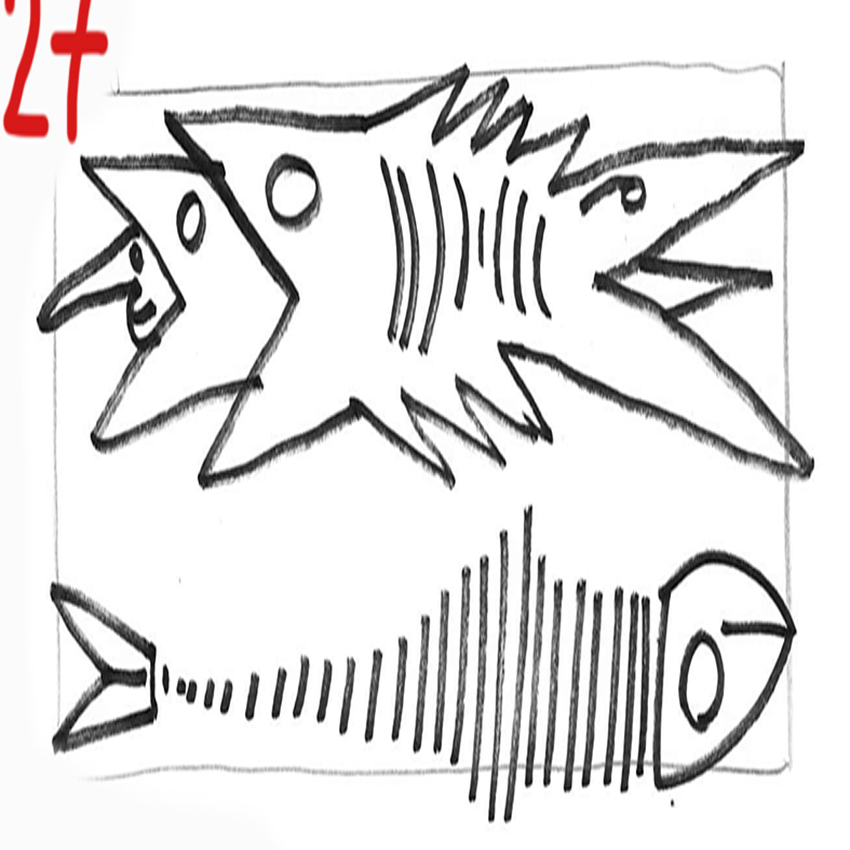

Histoire des monstres 02 bis, Lagos-Andura piscis, 24×42. Histoire des monstres 11 ter, Camp de César-Niliaca Parei, 24×42.

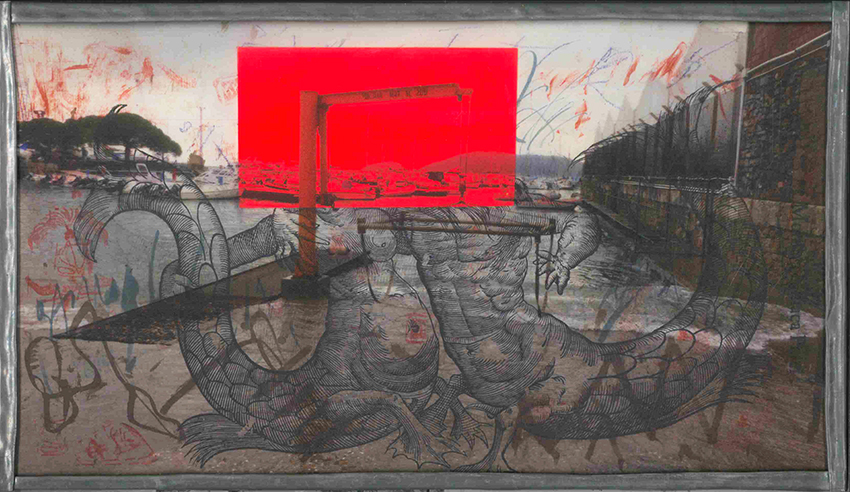

Histoire des monstres 11 ter, Camp de César-Niliaca Parei, 24×42.

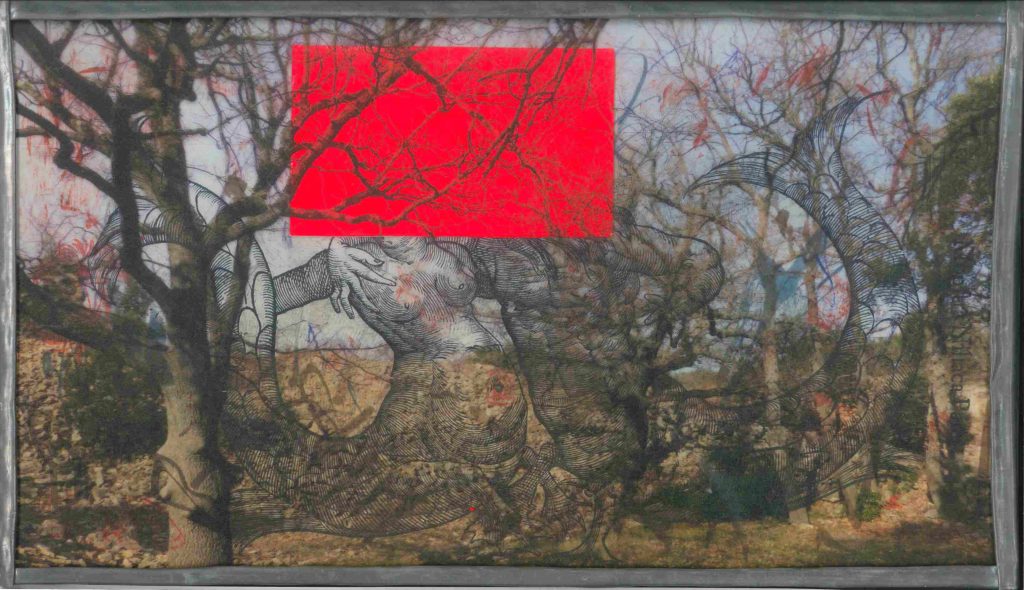

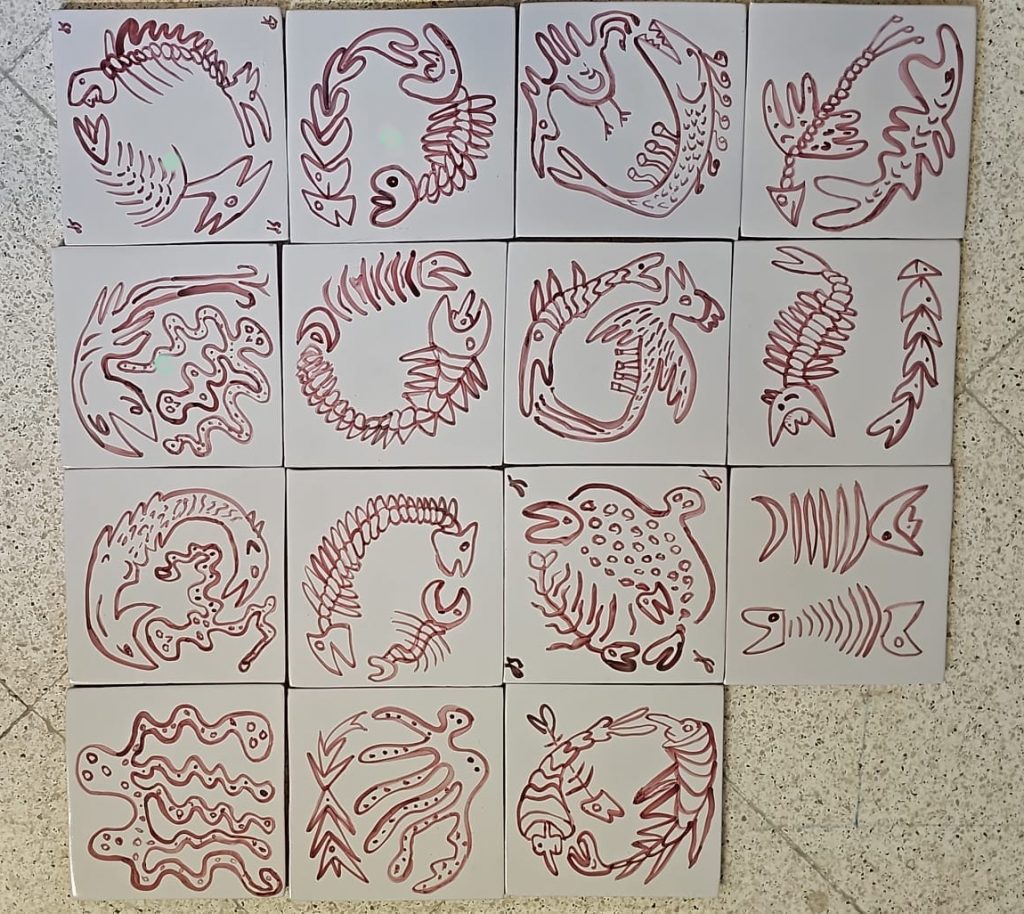

Polytechnio 01 (Tryumph of Semele), 26×42, 2023.

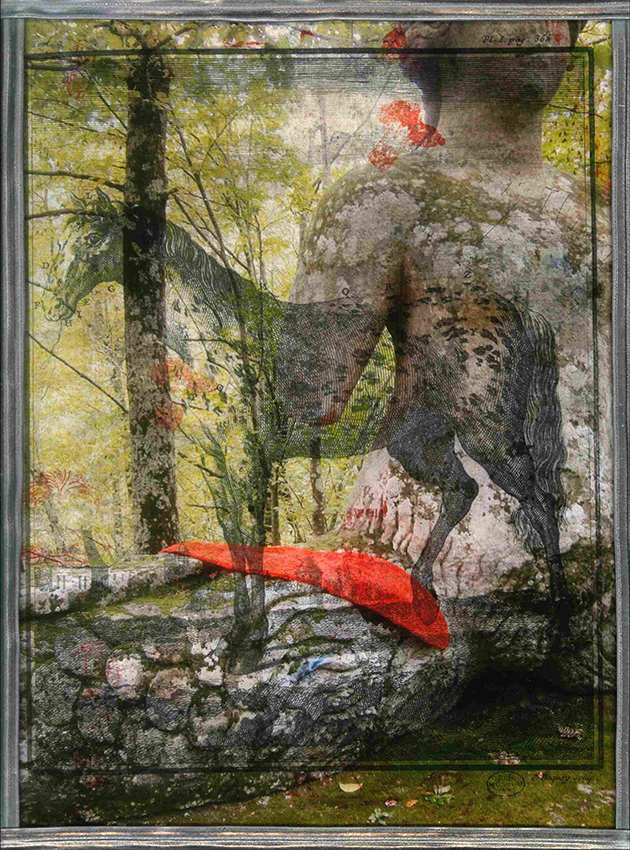

Polytechnio 01 (Tryumph of Semele), 26×42, 2023. Polytechnio 02 (Poliphilus encounters the Woolf), 26×42, 2023.

Polytechnio 02 (Poliphilus encounters the Woolf), 26×42, 2023. Polytechnio 03 (Dream of Poliphilus), 26×42, 2023.

Polytechnio 03 (Dream of Poliphilus), 26×42, 2023.

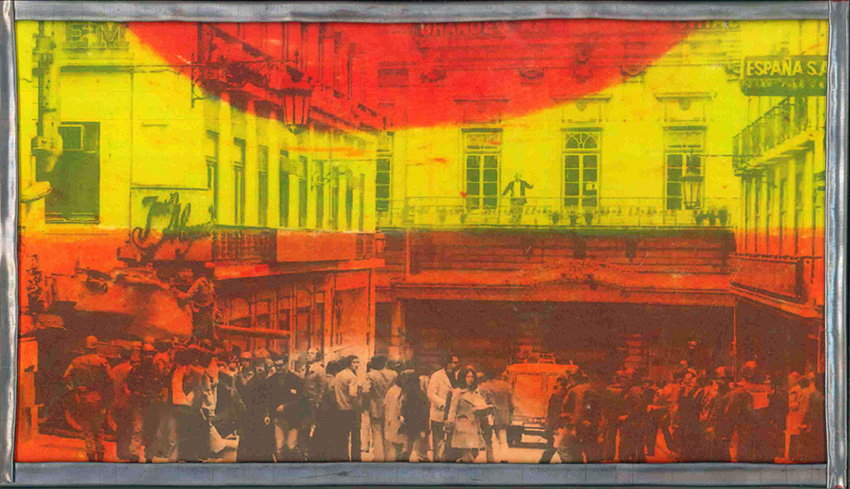

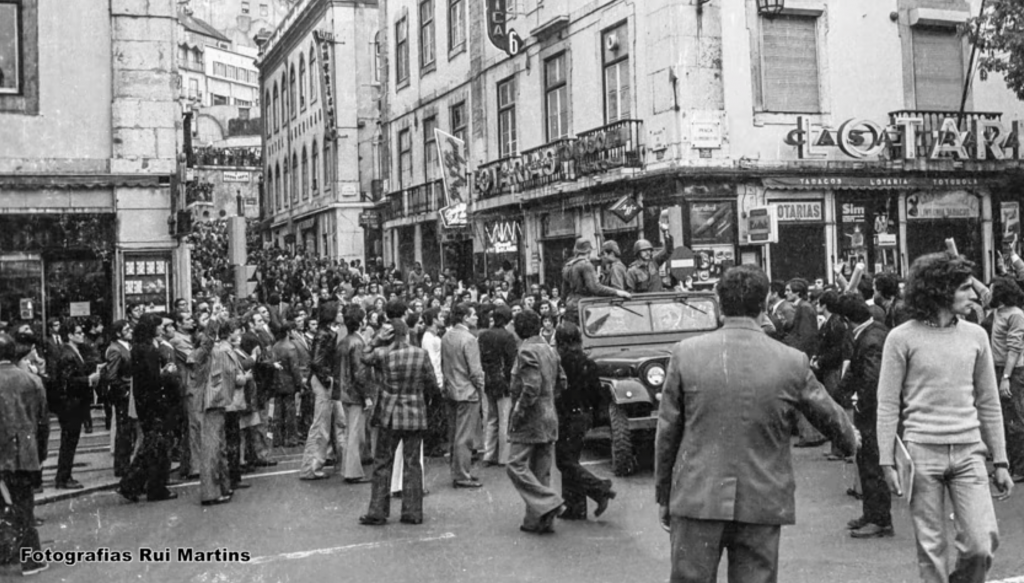

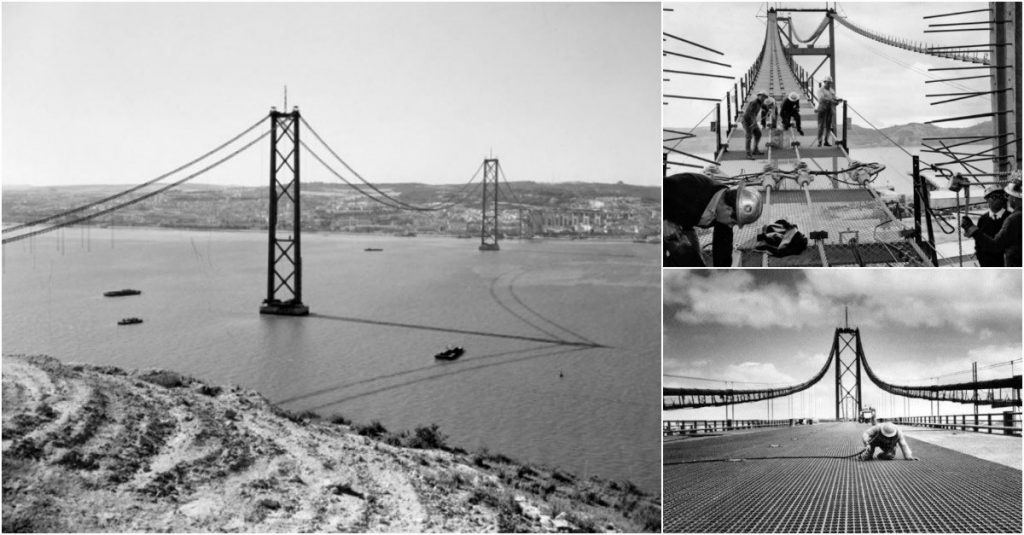

Cravos 01

Cravos 01 Cravos 02

Cravos 02 Cravos 03

Cravos 03

La Buoncostume remix 01-03, 42×20 apiece, 2023.

La Buoncostume remix 01-03, 42×20 apiece, 2023.

Forme, tryptic, 18×12 cm apiece, 1979

Forme, tryptic, 18×12 cm apiece, 1979 .

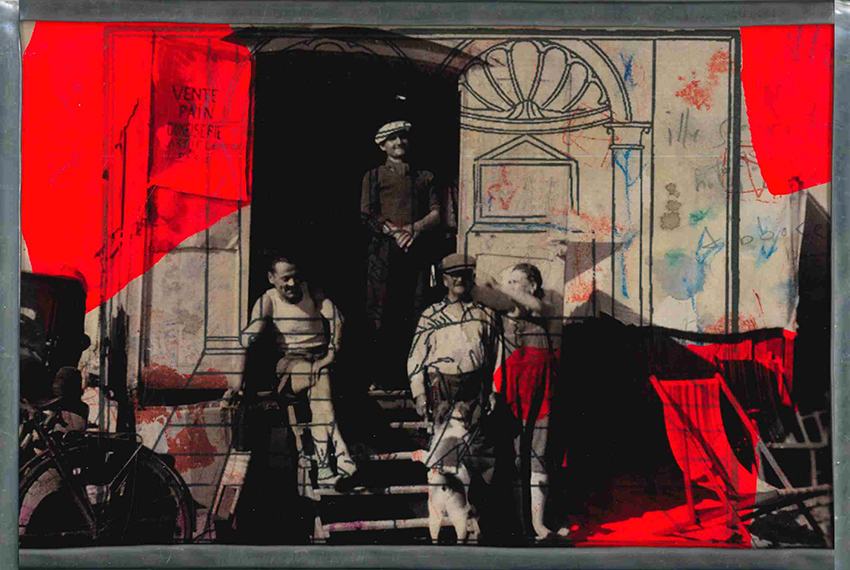

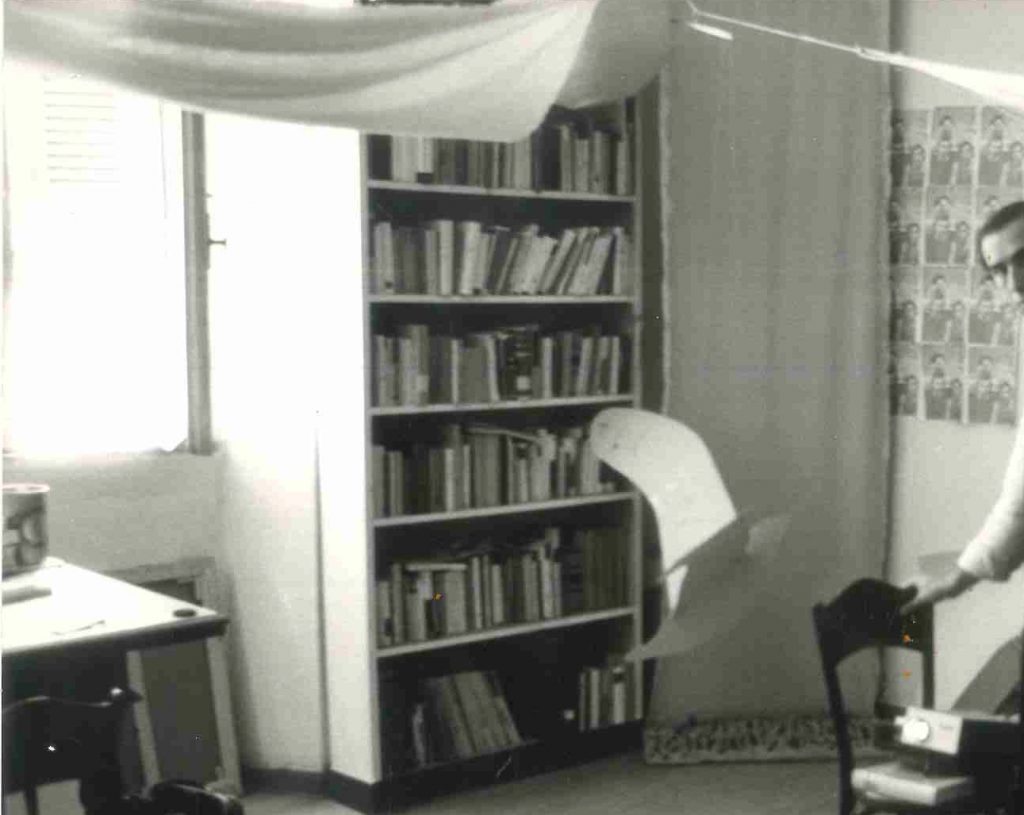

. Via del Paradiso, Roma, 1980. Tre opere: un montaggio di fotografie dipinte (tre amici a Londra), cocci di bottiglia infissi nel cemento e sormontatati da un telo dipinto d’azzurro, un ”mobile” uccello alla Braque. Sulla sedia un proiettore di diapositive, con il quale proiettai dalla finestra i miei primi acquerelli sul muro laterale della chiesa di S. Andrea della Valle.

Via del Paradiso, Roma, 1980. Tre opere: un montaggio di fotografie dipinte (tre amici a Londra), cocci di bottiglia infissi nel cemento e sormontatati da un telo dipinto d’azzurro, un ”mobile” uccello alla Braque. Sulla sedia un proiettore di diapositive, con il quale proiettai dalla finestra i miei primi acquerelli sul muro laterale della chiesa di S. Andrea della Valle.

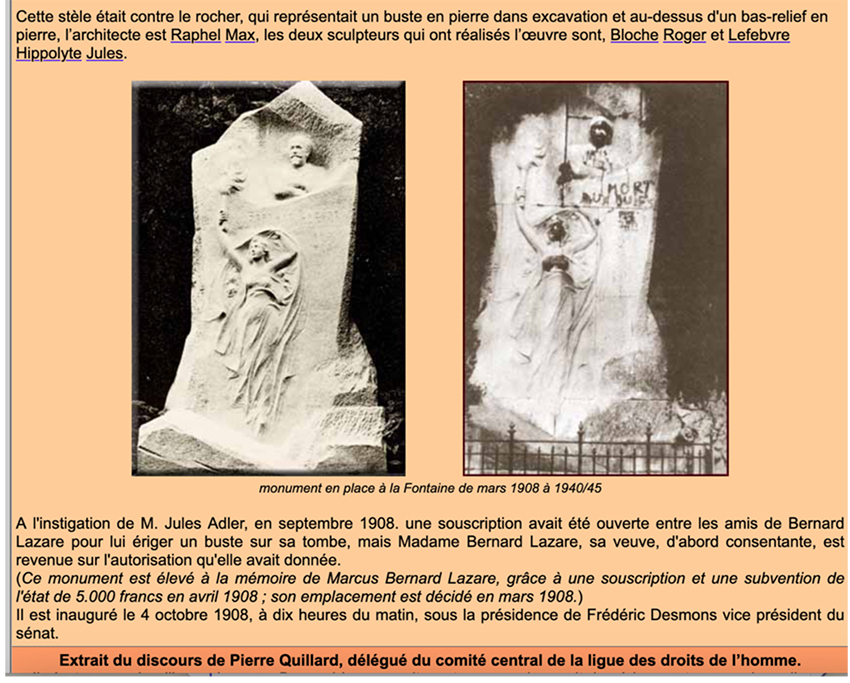

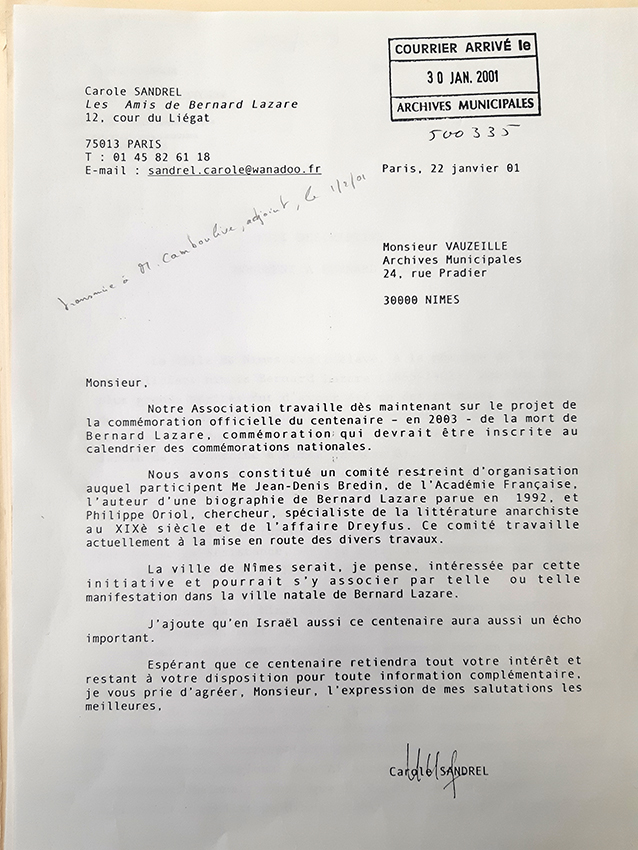

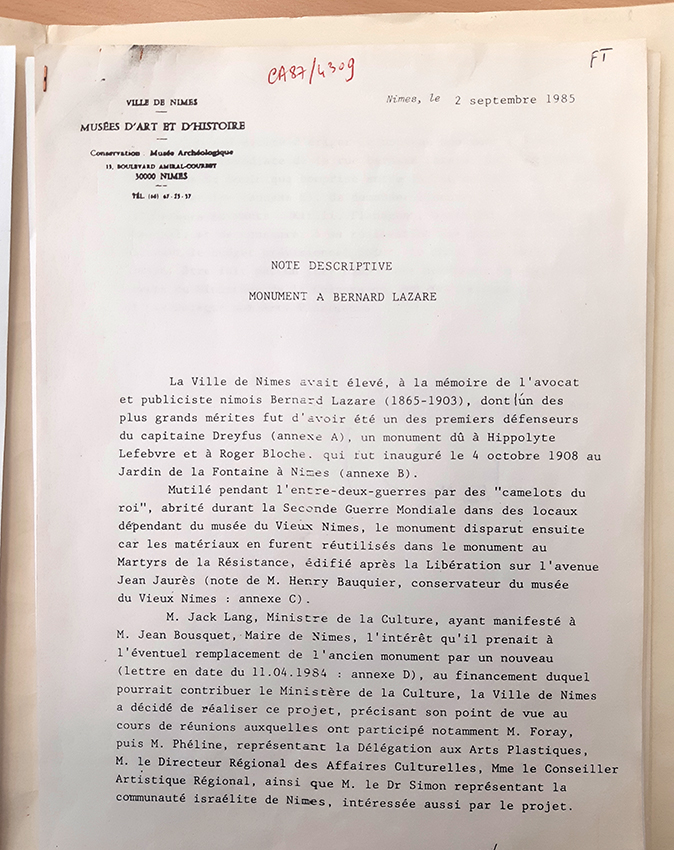

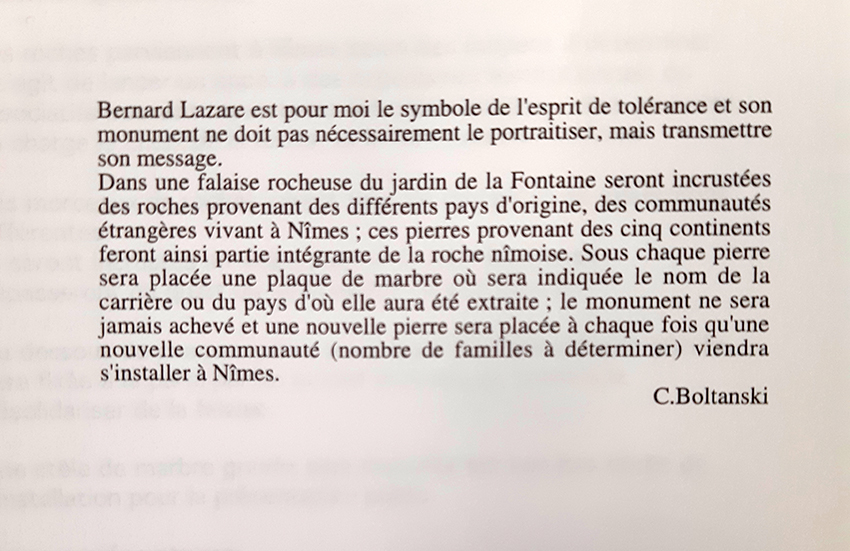

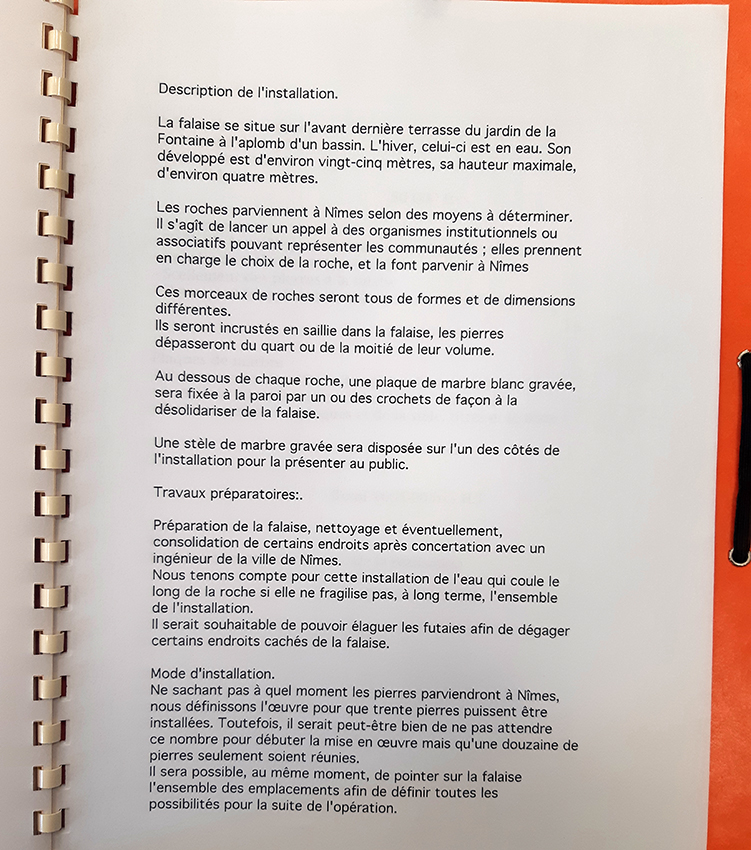

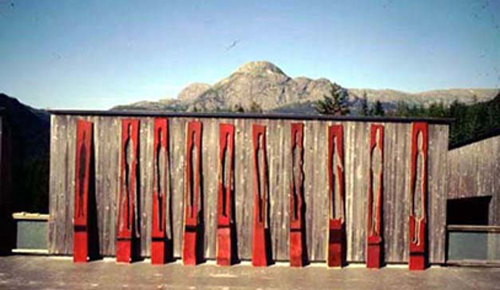

Le monument aux Martyrs de la Résistance, boulevard Jean Jaurès à Nîmes (Photo Stéphane Mahot, 2016).

Le monument aux Martyrs de la Résistance, boulevard Jean Jaurès à Nîmes (Photo Stéphane Mahot, 2016).

(D’après le site

(D’après le site

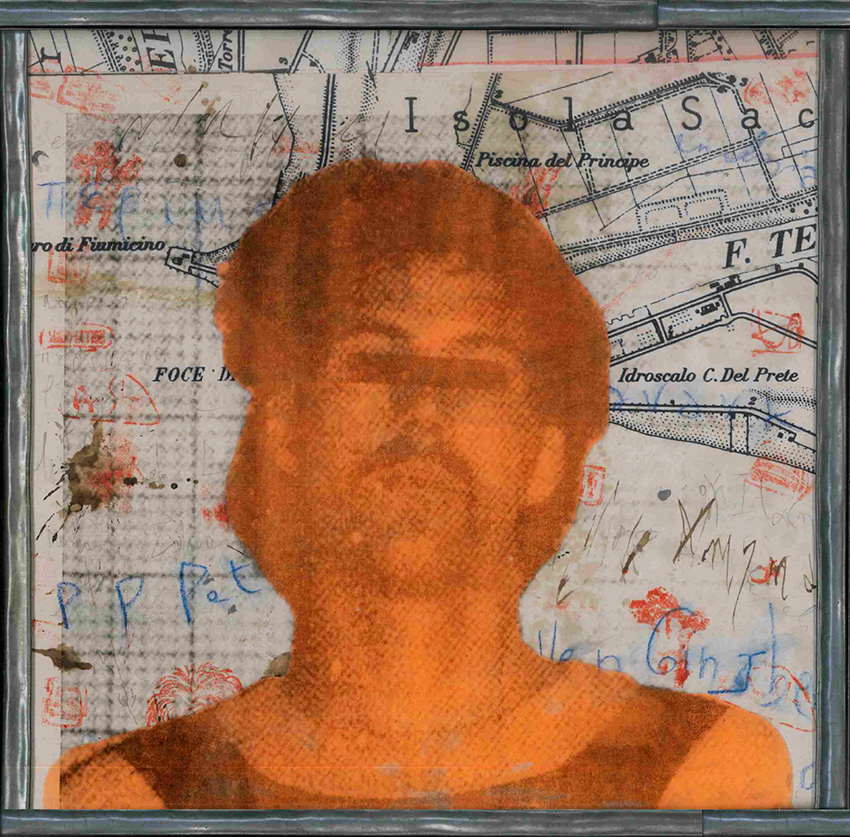

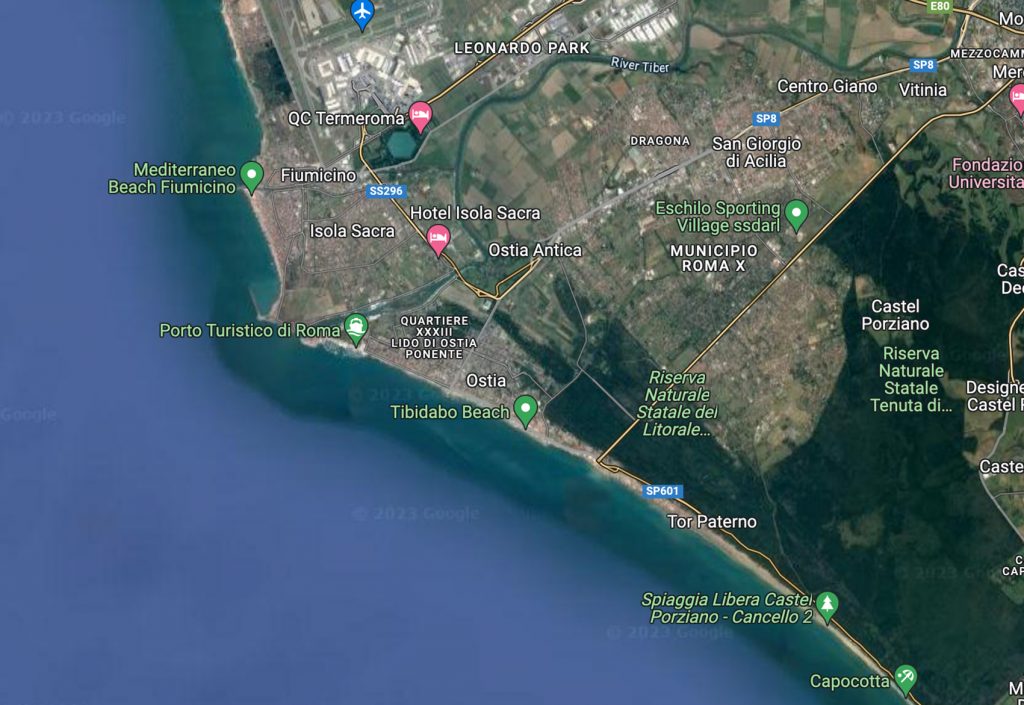

Anni Settanta 01, Idroscalo, 32×32, 2023.

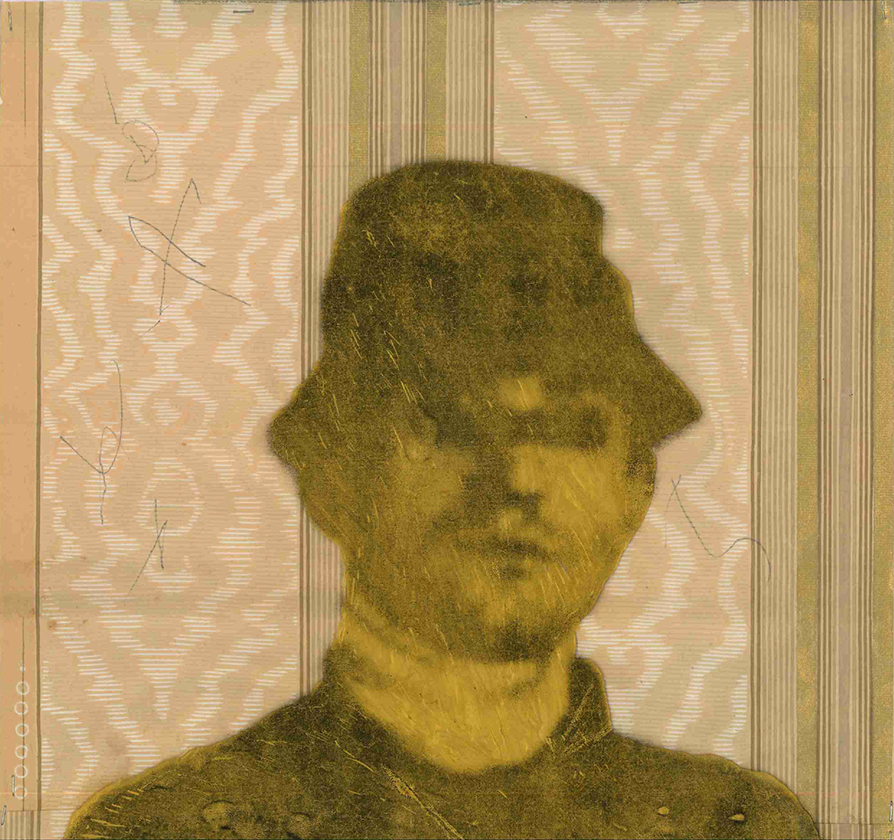

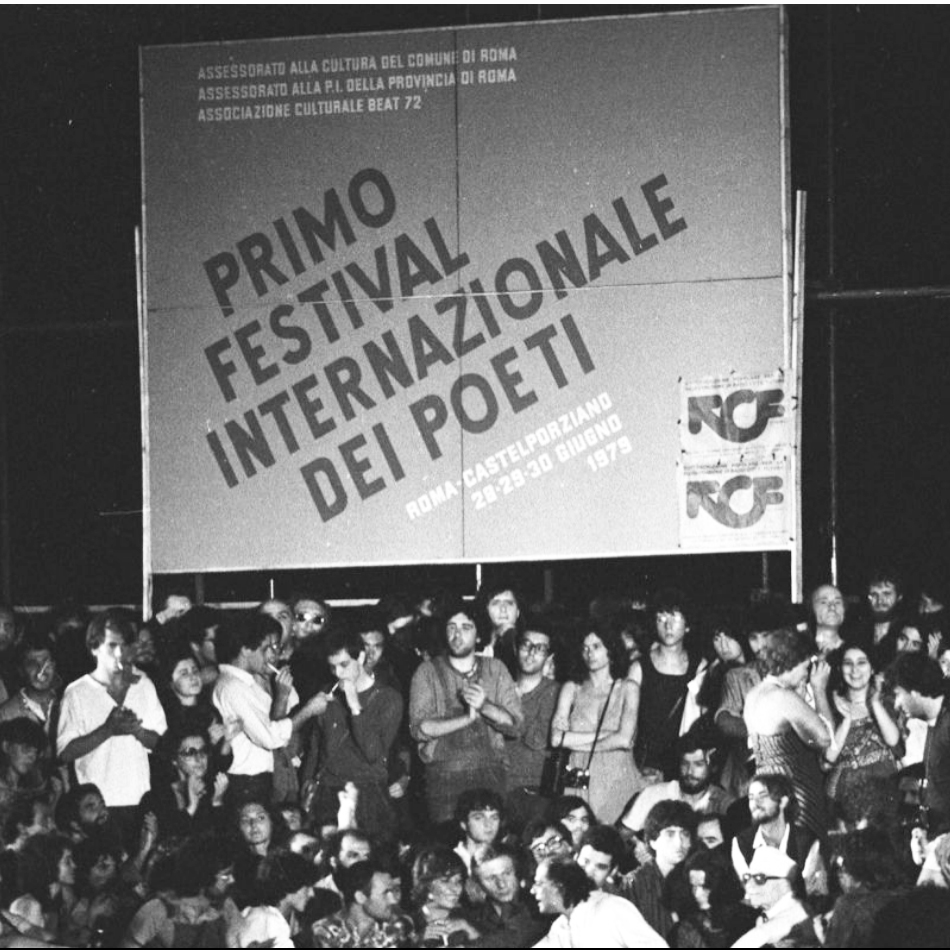

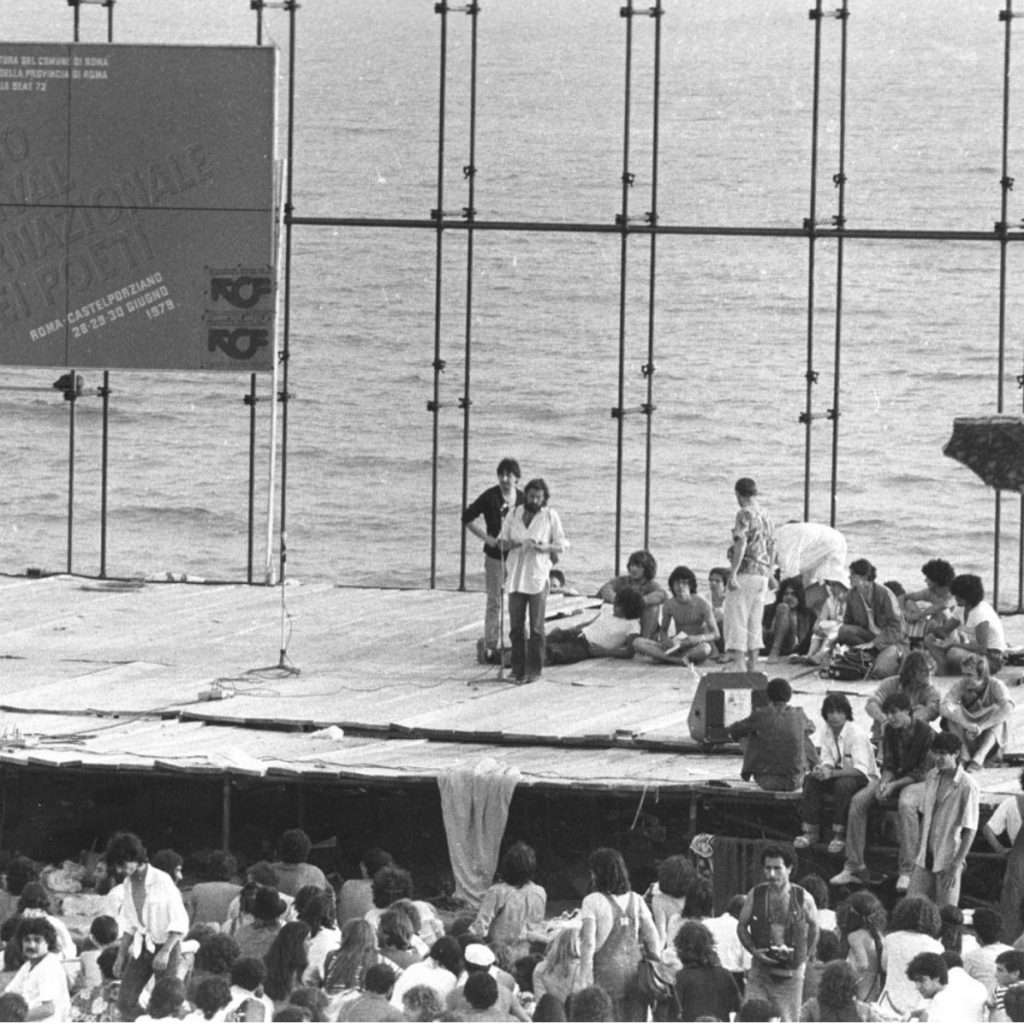

Anni Settanta 01, Idroscalo, 32×32, 2023. Anni Settanta 02, Castelporziano, 32×32, 2023.

Anni Settanta 02, Castelporziano, 32×32, 2023. Anni Settanta 03, Capocotta, 32×32, 2023.

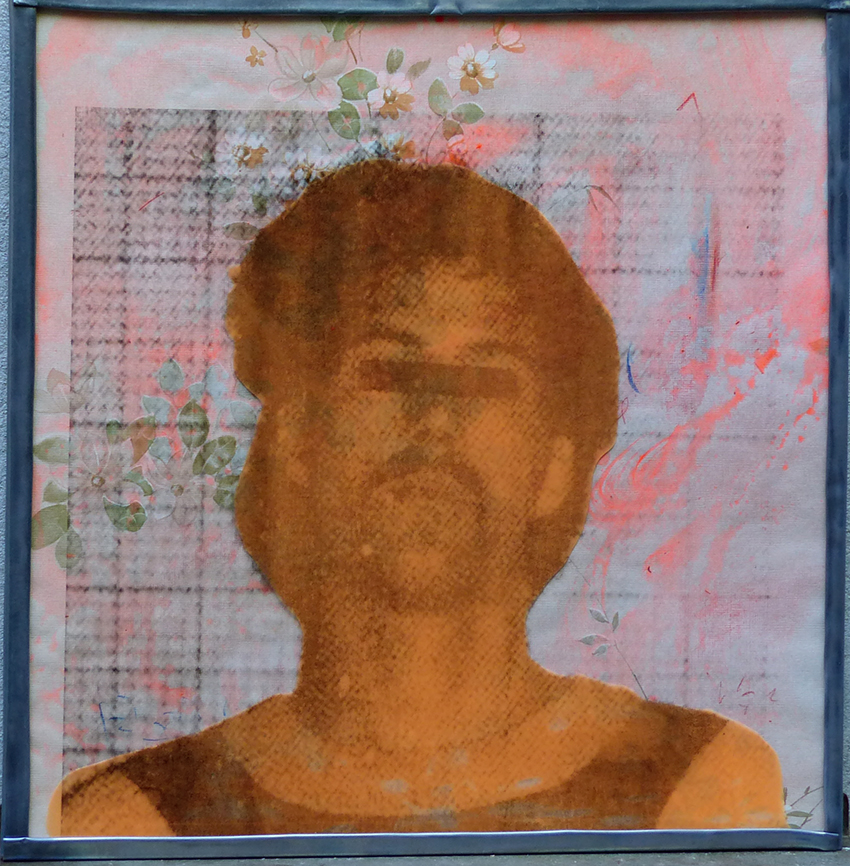

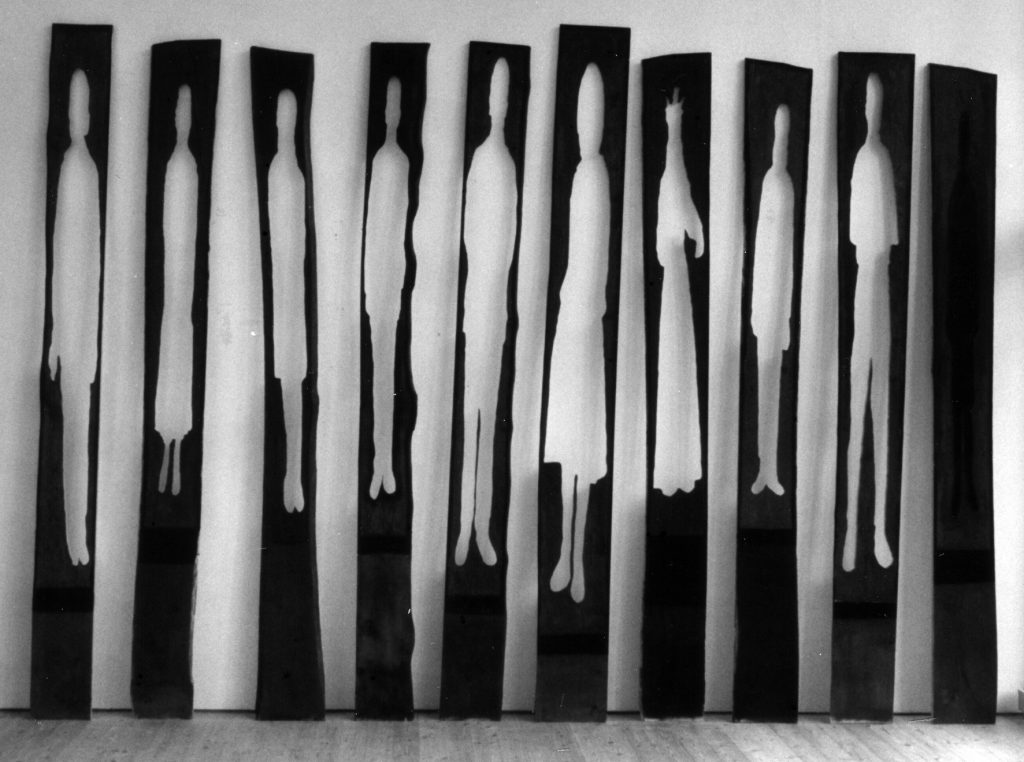

Anni Settanta 03, Capocotta, 32×32, 2023. Wallflowers remix 02, 32×32, 2010.

Wallflowers remix 02, 32×32, 2010. Wallflowers remix 04, 32×32, 2010.

Wallflowers remix 04, 32×32, 2010. Wallflowers remix 06, 32×32, 2010.

Wallflowers remix 06, 32×32, 2010.

Préface

Préface

01, 30×40.

01, 30×40. 02, 30×40.

02, 30×40. 03, 30×40.

03, 30×40. 04, 30×40.

04, 30×40. 05, 30×40.

05, 30×40. 06, 30×40.

06, 30×40. 07, 30×40.

07, 30×40. 08, 30×40.

08, 30×40. 09, 30×40.

09, 30×40. 10, 30×40.

10, 30×40. 11, 30×40.

11, 30×40. 12, 30×40.

12, 30×40.

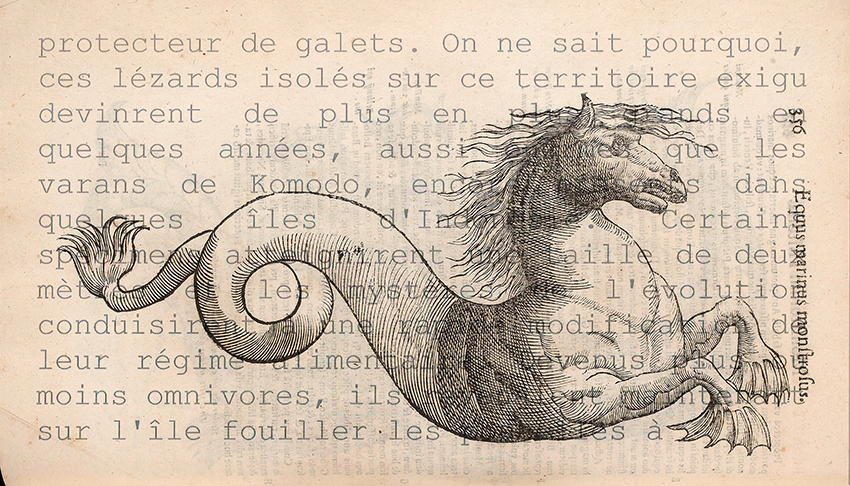

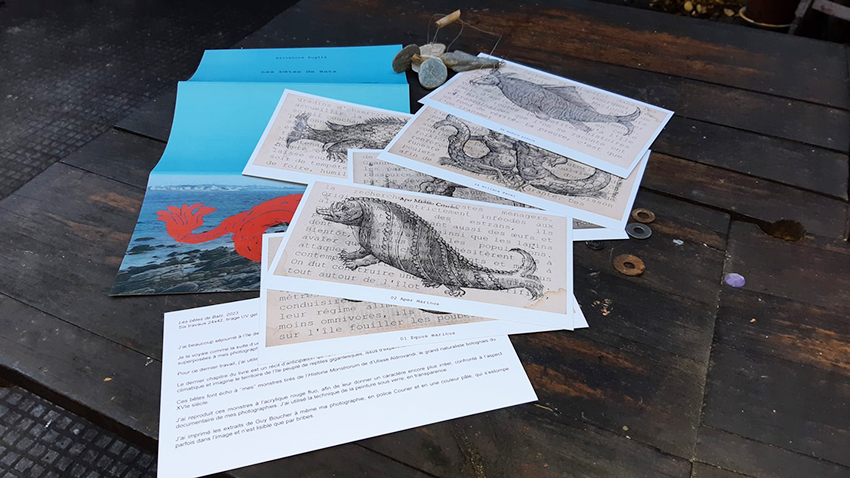

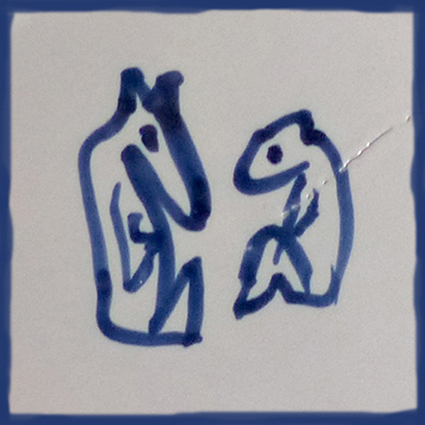

Les bêtes de Batz 01 Equus marinus (sold).

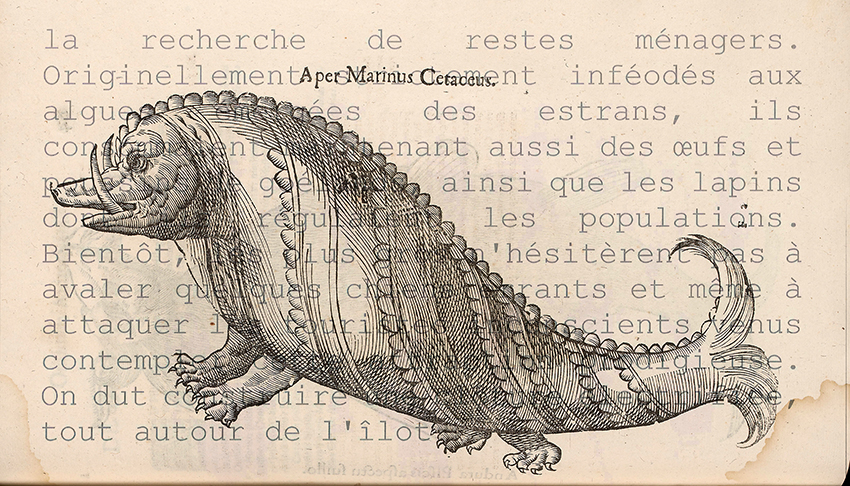

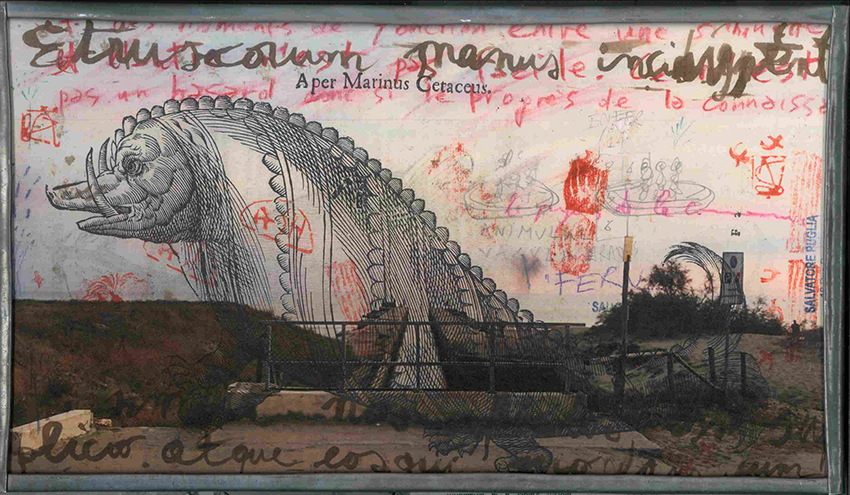

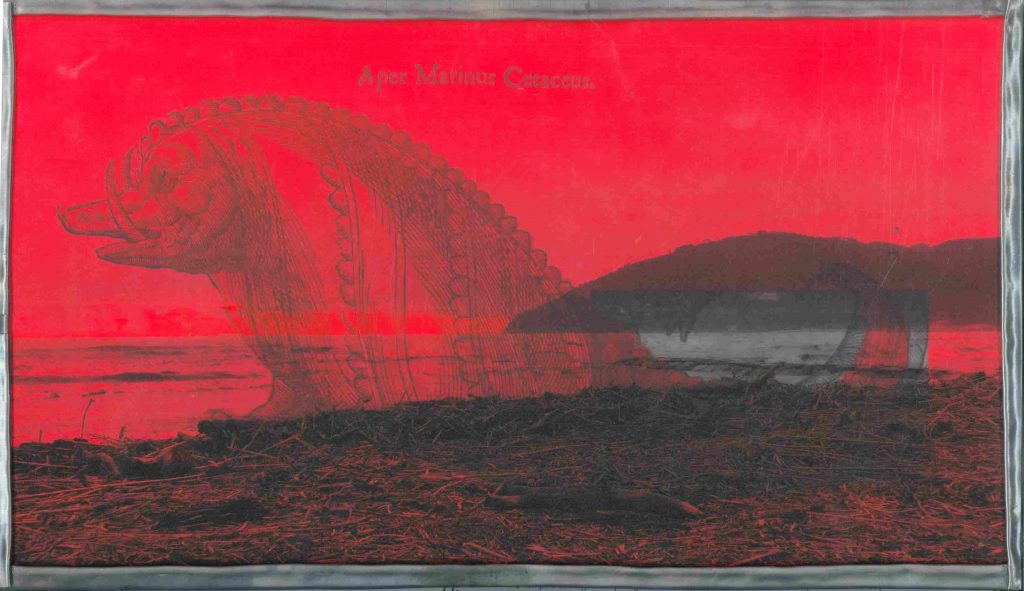

Les bêtes de Batz 01 Equus marinus (sold). Les bêtes de Batz 02 Aper Marinus

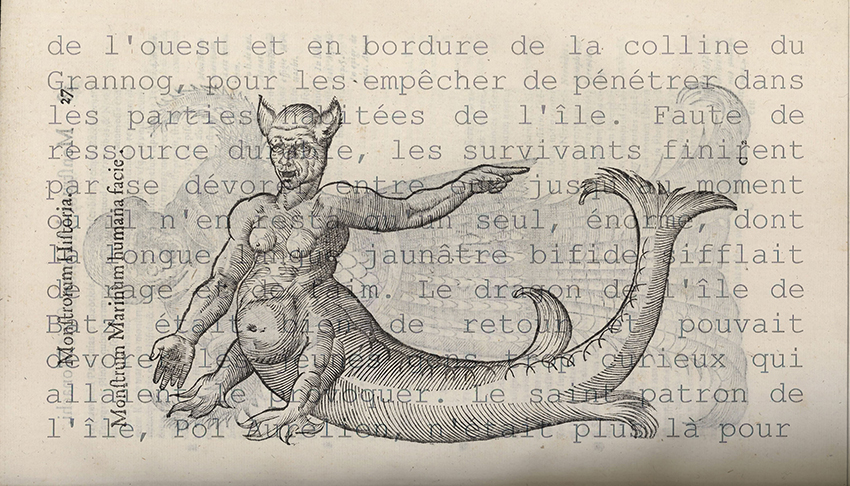

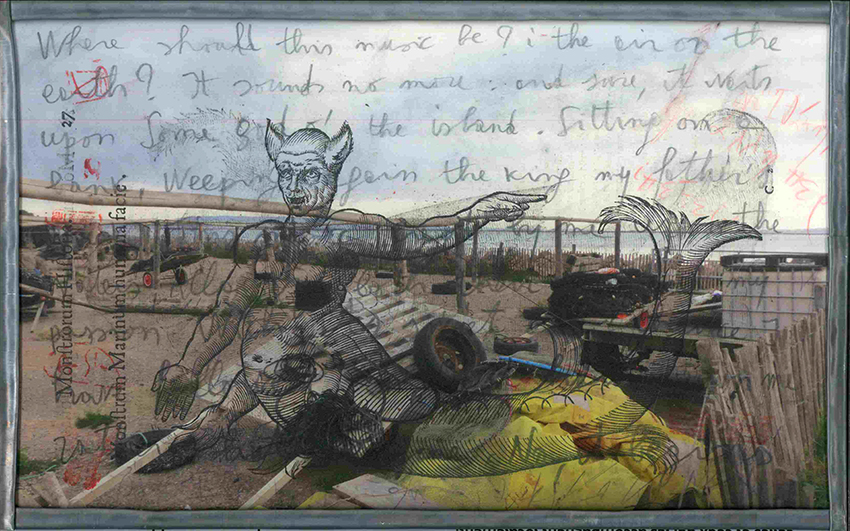

Les bêtes de Batz 02 Aper Marinus Les bêtes de Batz 03 Humana facie

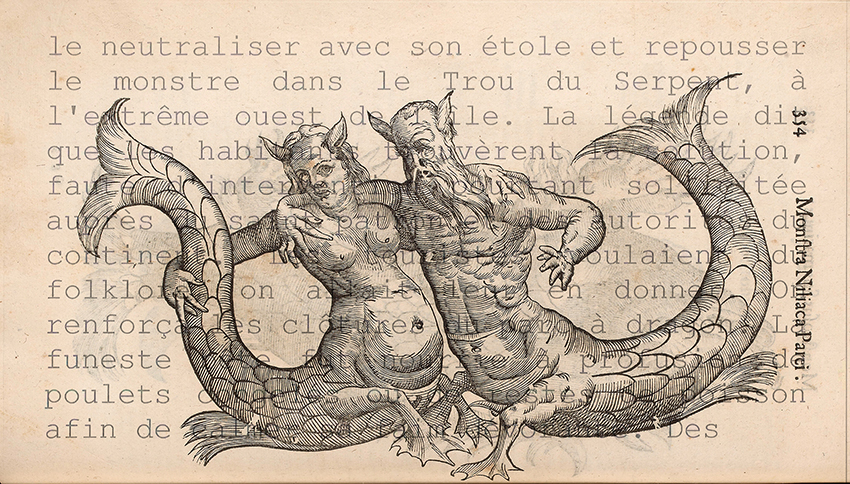

Les bêtes de Batz 03 Humana facie Les bêtes de Batz 04 Niliaca Parei

Les bêtes de Batz 04 Niliaca Parei Les bêtes de Batz 05 Sus marinus

Les bêtes de Batz 05 Sus marinus Les bêtes de Batz 06 Andura Piscis

Les bêtes de Batz 06 Andura Piscis