This work is entitled Laralia. The dictionary tells us that, in ancient Roman times, the Lares were the ancestors’ spirits, whose images, made out of painted wood or cast wax, were collected and worshipped in a specially designated part of the mansion called the Laralia.

These pictures were periodically displayed in processions, and then set on fire. Pliny the Elder mentions them in the section of Naturalis Historia devoted to painting (Book, XXXV, 6-7): in his criticism of modern art then in vogue, he underlines the moral value of these portraits, which served not only to commemorate the deceased, but also to accompany the living, so that “when somebody died, the entire assembly of his departed relatives was also present”.

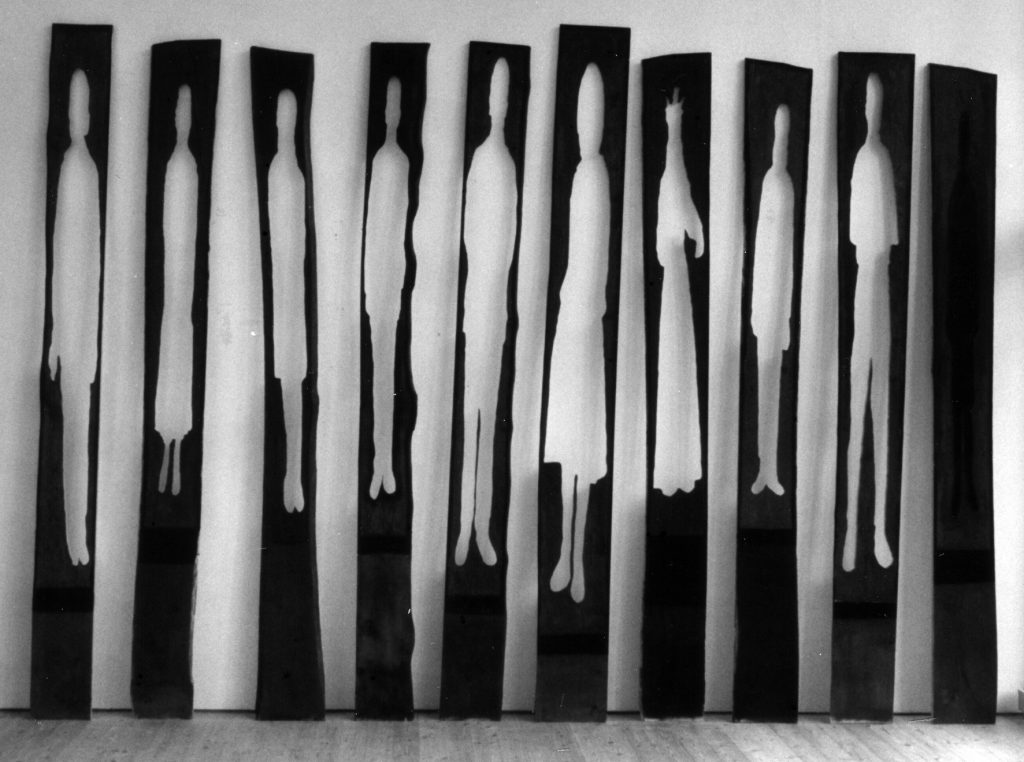

Ten pictures of local people, chosen at random among the ones conserved at the Fjaler Folkbibliotek, have undergone a multi-staged process of transformation: first, they are deformed in order to reveal their Anamorphosis, reminiscent of the long evening shadows; then, they are enlarged to life size; finally, their silhouettes are traced and cut out on boards of pine wood.

These black silhouettes were placed atop Dalsåsen Hill and then set on fire, in a brief ceremony.

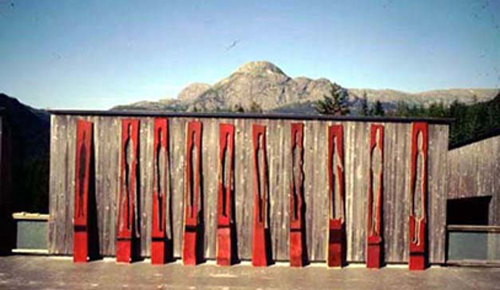

On the other end, the three-meter high plates, from which the silhouettes had been carved out, were erected in the Øvstestølen Plateau, above Dale, in a spot visible from the Jøtelshaugen Peak. Painted in oxide red, these steles turn their backs to the west, so that, at the end of the day, around mid-August, the shadow of each top touches a stone, under which the original picture of the corresponding individual has been placed.

This work is mobile. During the day, in sunlight, the shadows on the ground change shape, cross each other and are, for a fleeting moment, similar to the original picture.

The instantaneous freezing of the photographic image documents a unique state of a person and is meant to be recognisable by the person’s relatives and the collective memory. In Laralia this image is subjected to multiple reproductions, which progressively distance the subject from its departure point.

The final stage of this process – the woodcut – is the opposite of the photographic image, in terms of the time and energy required for its execution; the slowness can be seen as a less tyrannical and intense way of recording the image.

The ten pictures, transformed into steles whose commemorative function is only vaguely related to the individuals they portray, will surrender to the action of time and nature, which will further modify them and ultimately lead to their decay.

This work is not intended to be a mere celebration of local history. Instead, it is an attempt to finding a sign or a “monogram”, of vanished individualities that could possibly remain after a progressive flattening of the recorded images. Perhaps this process mirrors the functioning of our memory, with its arbitrary choices, gaps and repetitions and constitutes an attempt to navigate between the opposing poles of amnesia and hypermnesia, forgetfulness and obsession.

(A short movie by Knut Nikolai Bergstrom, 3’32”)

Note: for a journal of this installation, see Diario Boreale, interrotto. And, also in Italian, a transcribed notebook: Taccuini scandinavi 1999-2000.