Return to Cythera PDF rough version.

.

(Ruins in the island)

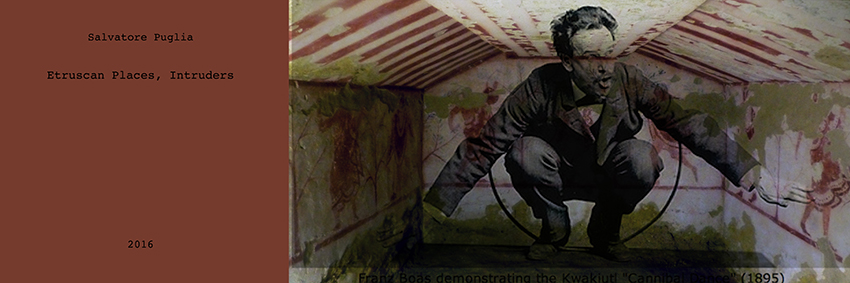

The main concern of this writing is the relationship of a contemporary artist to Greek and Roman Antiquity. This relationship is viewed through the works of several poets, painters, architects, who have also dealt with antiques.

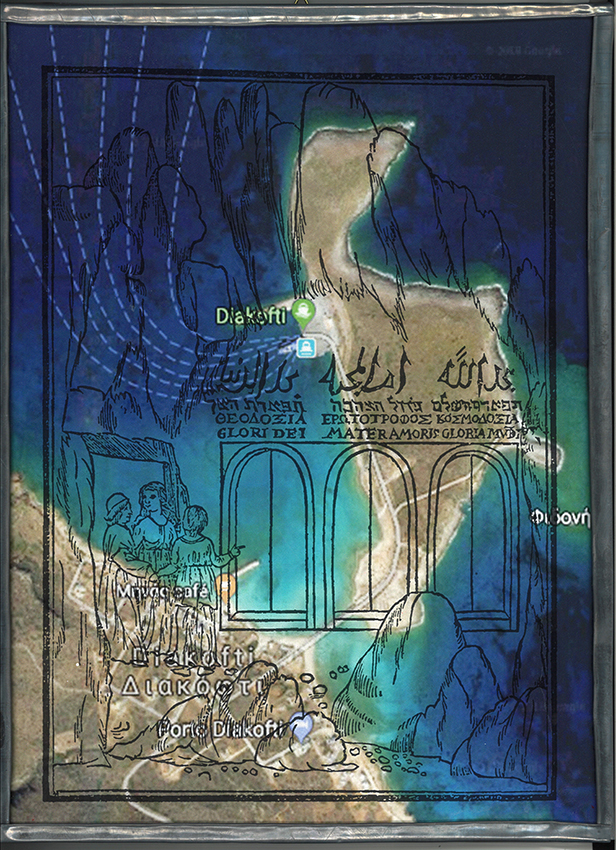

(01 Kithira google, see Images Chapter 1)

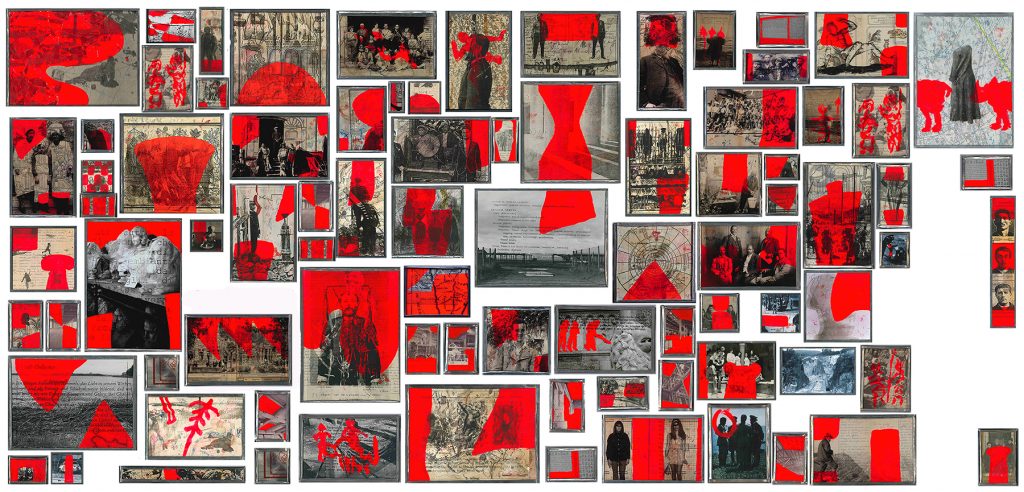

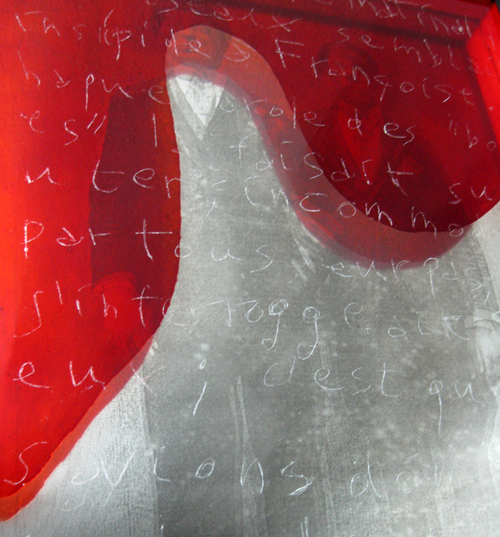

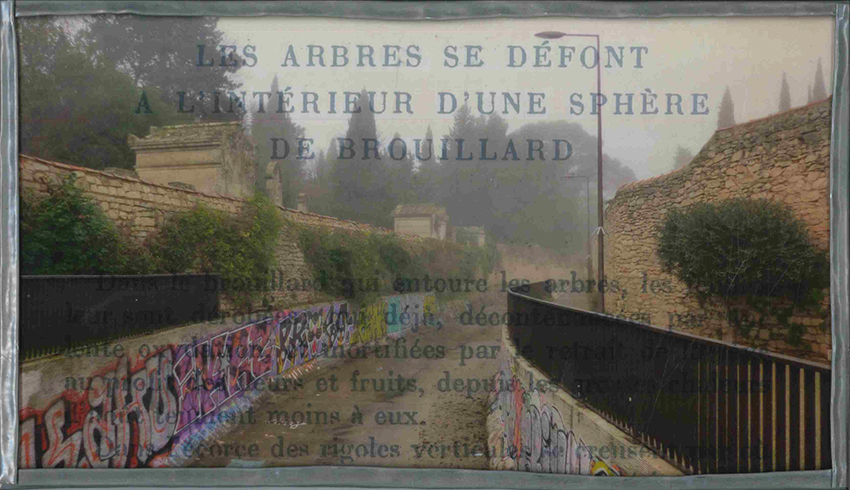

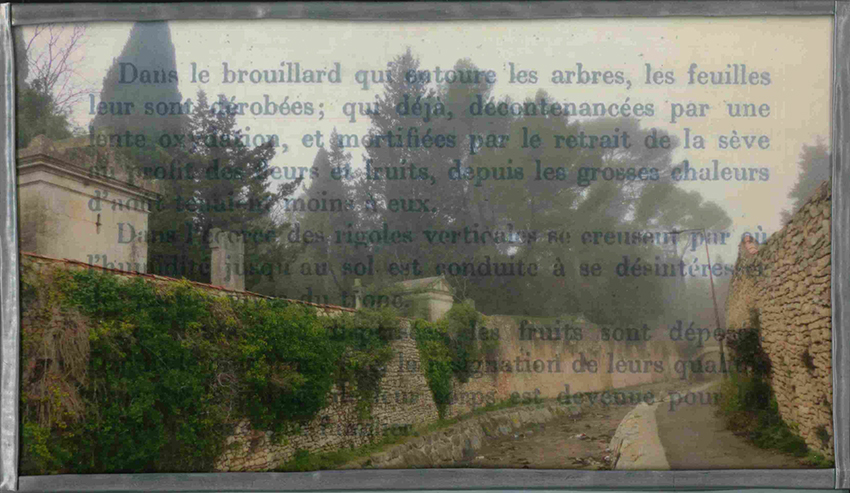

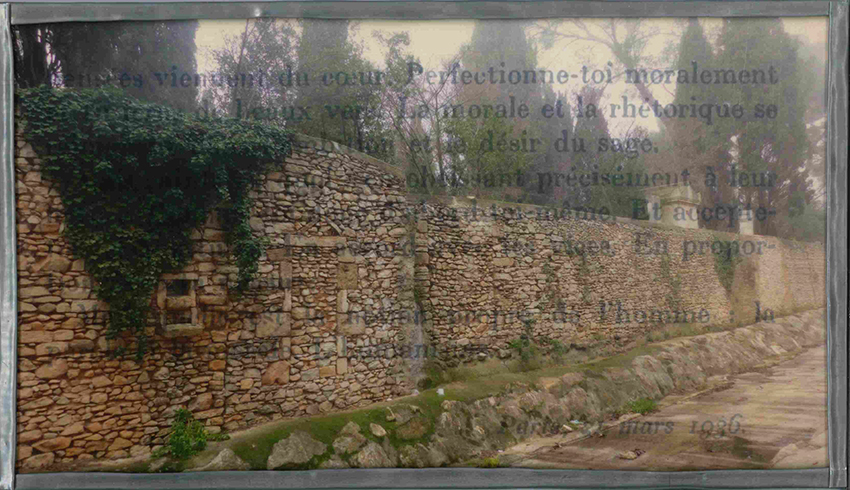

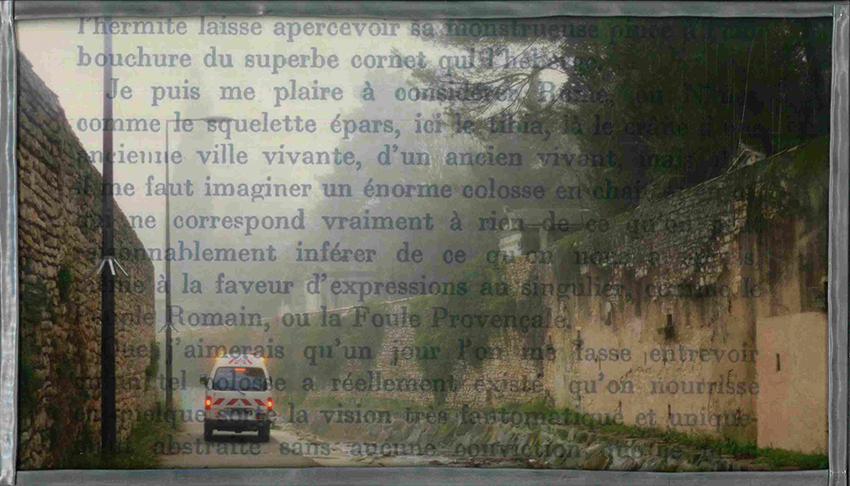

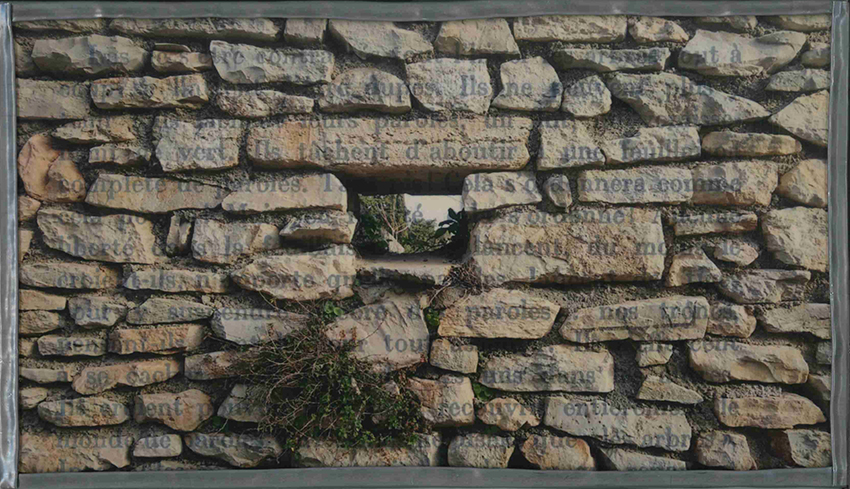

To illustrate my point, a long digression on the subject of landscape will be necessary. I will survey those aspects of my work dealing with “historicized” nature and “naturalized” history. My work is necessarily photography-based, in which the photograph is always somehow “modest”, never spectacular. And this not only because I consider a photograph to be “just” a document, but also because I believe that such sobriety allows for further creative interventions and layering.

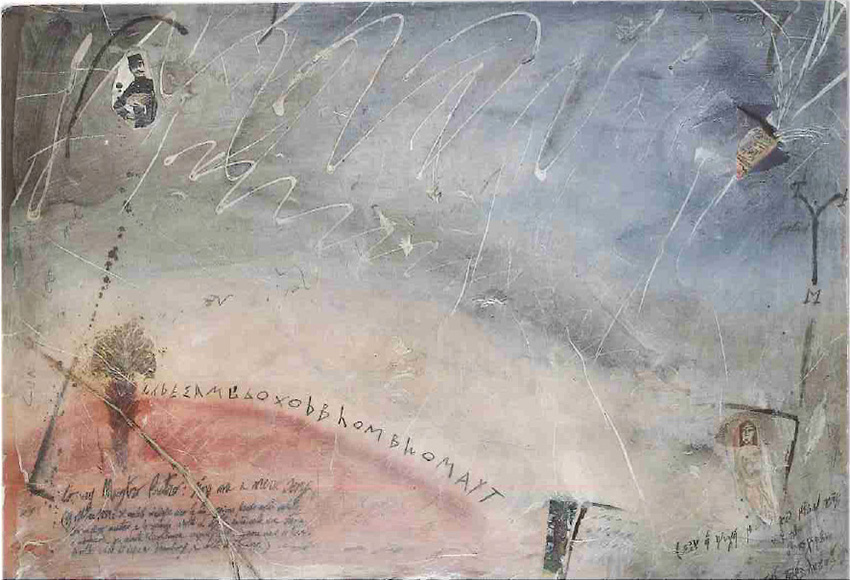

You will also see that the images I use have the same function as the text, a kind of “performing” interpretation of History. This same interrelation between text and image is, in my mind, central not only to the last work I will mention, The Strife of Love in a Dream, but also to my visual translation of it.

.

Chapter one: Gulliver versus Robinson.

(Images for Return to Cythera Chapter 1)

(02 Gulliver 01)

My interest in landscapes resonates with my interest in intermediary spaces, which are not completely natural yet not yet fully “humanized”. The photographs for the series Gulliver in Lavéra were shot at dawn on a Sunday in winter, at the industrial site of Martigues, one of the largest petrochemical complexes in Europe, built in a once-idyllic spot on the Provence coast. Allow me to quote a passage from an article by Daniela Goeller, who describes it more eloquently than I can.

“The landscape is a complex construction. It is way of looking at an environment and exists only through the eyes of the viewer. More than a reflection of the outside world and the surrounding countryside, the landscape constitutes an ideal space for projection and reflects different artistic and political visions and concepts imposed by our civilization on nature through the centuries.” (1).

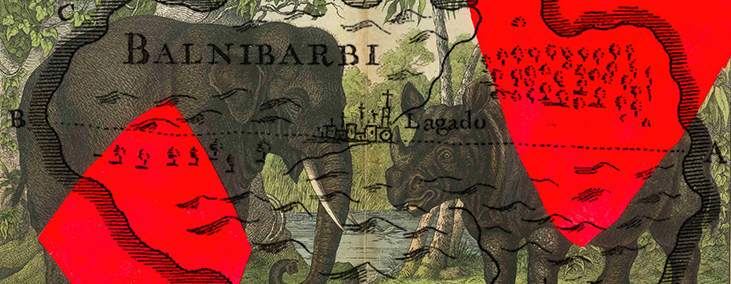

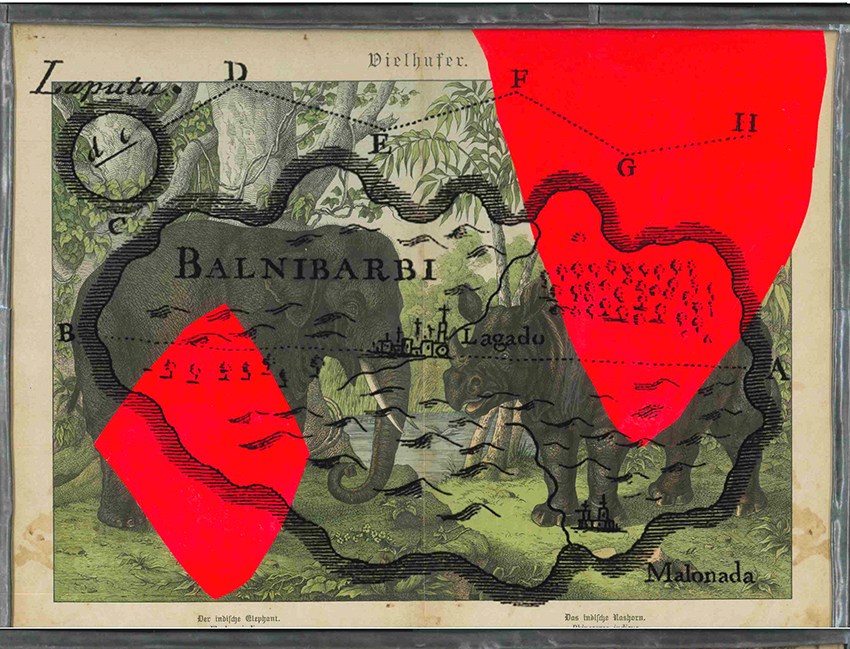

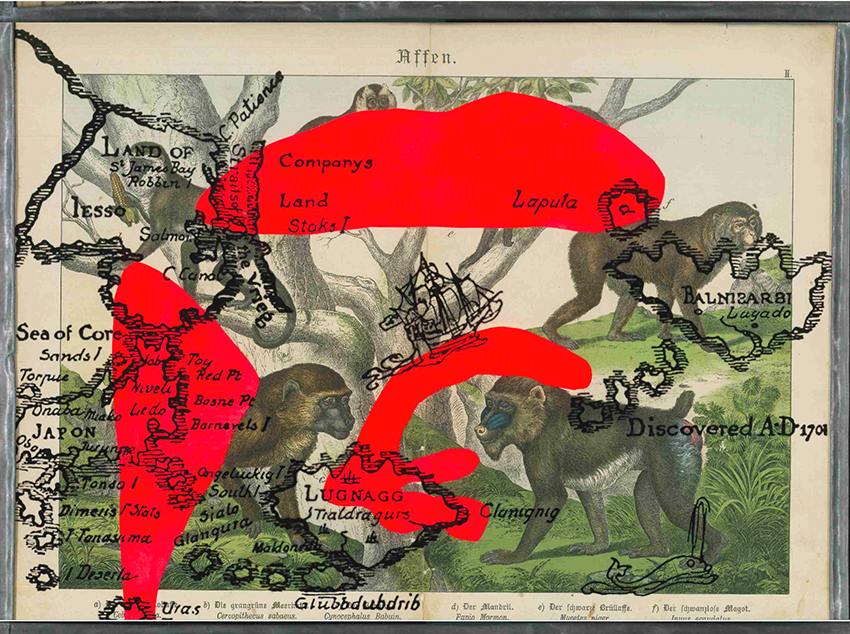

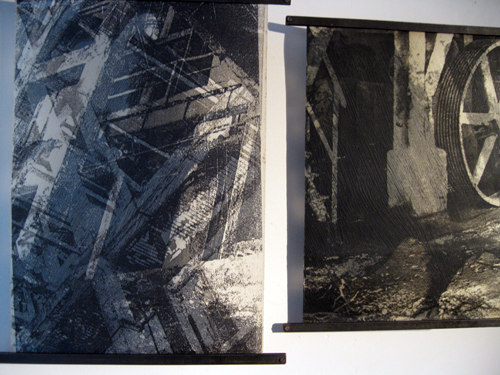

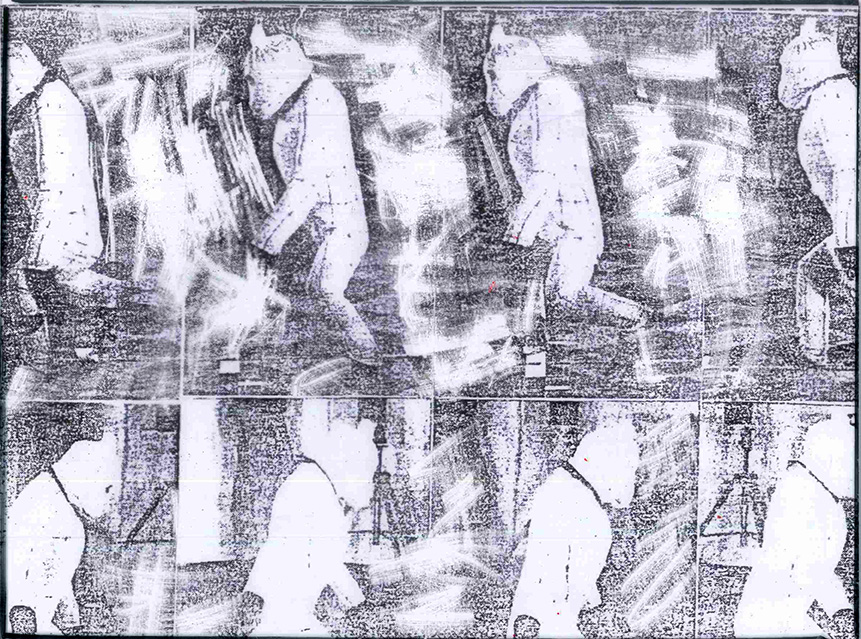

These images comprise different layers. In the foreground, a beach view fronting some industrial buildings. Then two layers: very diluted paint drippings that create a sort of cloud (or sun) upon drying; and printed on glass in the foreground — almost erased by the rudimentary method of transferring prints with trichloroethylene — are engravings from Gulliver’s Travels.

The choice to re-use and “re-engrave” illustrations of Gulliver’s Travels, an allegorical and satirical work by Jonathan Swift, with other historical images, is significant. The work was written in the 18th century, the Age of Enlightenment characterized by faith in justice and progress, which are subtly mocked by Swift. It is also the century of Piranesi and the romantic fascination with ruins, which is possible only if they are considered as a nostalgic remnant and not a real possibility; such an “enlightened” vision allows ruins to be used for decorative purposes.

(03-04-05-06-07 Gulliver à Lavéra)

The chemical plants that I imagine Gulliver finds on the shore instead of the Lilliputians, are not (yet) ruins. However it is worth mentioning that I conceived this work a few months before the Fukushima nuclear accident (March 2011), which demonstrates the enduring power of Nature and raises, once more, questions about where the Enlightenment Age is taking us. I did not want it to be an illustration of a contemporary event, and it took me long time before deciding to exhibit these pieces.

Here you have, five years later, a more colourful version of the work.

(08-09 Gulliver Montalto, Gulliver Aramon)

As a complement to the previous series, some months later, I created a few works named after the fictional character of Robinson Crusoe: Robinson a Rosignano.

(10 Robinson 04)

It is well known that Jonathan Swift wrote his famous novel, Gulliver’s Travels, partially as a reaction to Defoe’s optimistic vision of the relation between nature and humankind. I may be mistaken, but it could be argued that Swift is on the side of a “hard primitivism”, which would be more closely linked to materialistic philosophies, according to Erwin Panofsky in his article on a Piero di Cosimo (1466-1521) cycle of paintings, “The early history of man” (2); while Defoe could be on the side of a “soft primitivism”, let’s say more idealistically and “Golden Age” oriented (3).

(11-12 Piero di Cosimo)

Note that this painting presents no hierarchy, or psychological difference, between men, beasts and hybrid creatures. This is a vision of the early days of humanity that are neither biblical nor neo-Platonic. Note the difference with this other hunting scene, painted about thirty years earlier, in 1470, by another Florentine, Paolo Uccello (1397-1475). We also know that Piero di Cosimo was familiar with this work. Here nature is so completely submitted to human action that it becomes a demonstration of geometry.

(13 Paolo Uccello)

But, returning to my subject: in the Tuscany coast town of Rosignano Marittimo, there exists a stretch of white sand beaches that resembles a Caribbean landscape.

(14 Rosignano beach)

Although these beaches may appear natural and are appreciated by tourists in the summer season, they were created by the waste of a sodium hydroxide factory, owned by the Belgian firm Solvay.

(15 Rosignano Solvay)

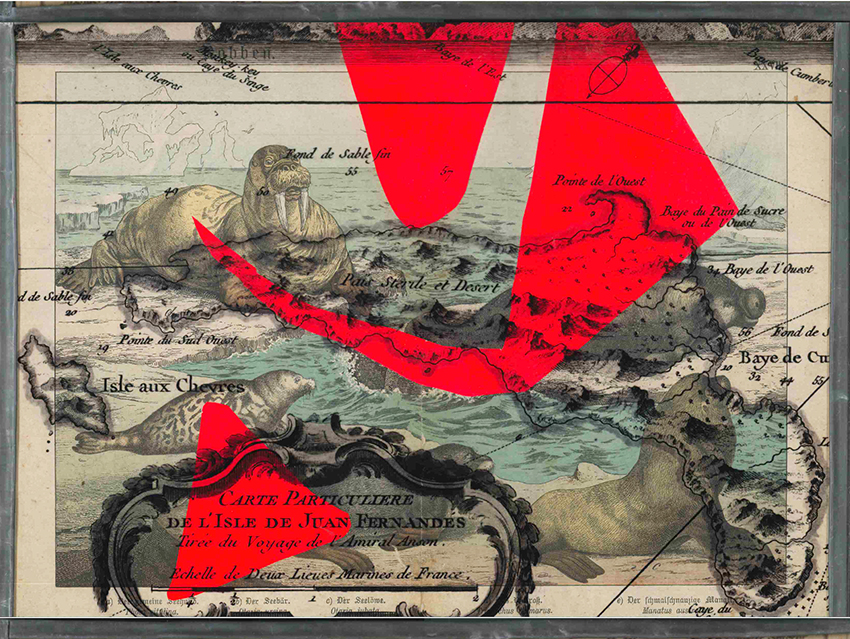

I visited to these beaches in wintertime (like many, I like seashores in winter) and photographed the site. Afterward, I combined these images with reproductions of traditional fishermen tools from Greenland, using red translucent paint, and engravings taken from various editions of Defoe’s book.

I imagined translating the very moment in which Robinson, not believing his own eyes, found the traces of human feet in the sand.

(16 Rosignano Winter, 17 Robinson 03, 18 Robinson 01, 19 Robinson 02 detail)

.

Chapter two: Nella selva antica.

(Images for Return to Cythera Chapter 2)

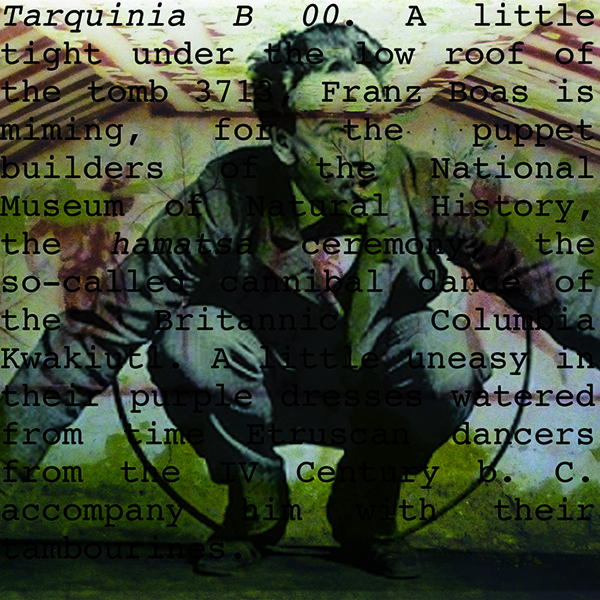

(01 Nella selva 02)

Four or five years ago, thanks to a friend’s advice, I discovered Robert Pogue Harrison’s essay on forests, published in 1992 (4). The concept that I took from it is that the forest is a human invention, a cultural contrivance. At that time, I was thinking about my literary models of a now-gone generation of intellectuals who experienced the Second World War in their youth: Nuto Revelli, Primo Levi and others. The last survivor was Mario Rigoni Stern (1921-2008). Born in the Asiago plateau, an area heavily damaged during World War I, Rigoni was influenced by nationalistic rhetoric and wanted to pursue a military career. However before long he became convinced of the injustice of the war, a conviction that was further strengthened during his service in the Italian Expeditionary Corps in Russia, in the disastrous retreat of January 1943. Rigoni was one of the 60,000 ‘Alpini’ elite military corps that Mussolini sent to occupy the Soviet Union, and among the fortunate 20,000 that returned home safely.

A second “anabasis” experience occurred to him two years later, during his escape from a German military concentration camp in April 1945. For ten days, Rigoni wandered through the Styria and Carinthia forests in Austria surviving on berries, bird eggs and snails before encountering an outpost of Italian partisans at an Alpine pass.

The theme of the forest, as that natural site completely destroyed by Austrian and Italian bombs between 1915 and 1918 and subsequently replanted, exemplifying the ‘artificial’ that laboriously reverts to a natural state, is central to Rigoni’s oeuvre.

(02, 03 Monte Zebio, 04 after the bombing, 05 Asiago front, 06 replanting the forest)

For Rigoni, the forest is a mirror of the world “as it should be”, a world where “siamo tutti compaesani” (we all belong to the same village). In this ecosystem, we can all live together, men and animals of various species, once the environmental carrying capacity is under control.

(07, 08 Rigoni Stern)

But, according to Rigoni, the “good” forest is not the one that grows spontaneously and wildly. Rather the “good” forest is the one tamed by human labour, where humankind plays the role of caring gardener.

As I wandered, as a tourist, around Rigoni’s homeland I recorded some images of forests, which, upon closer inspection, reveal traces of the war: the collapsed trenches, the craters created by bombs. There I encountered a theme of my Rupestrian series: these sites are also taken back by nature, even if here the traces left behind are the result of humankind’s diabolical engineering rather than its creativity.

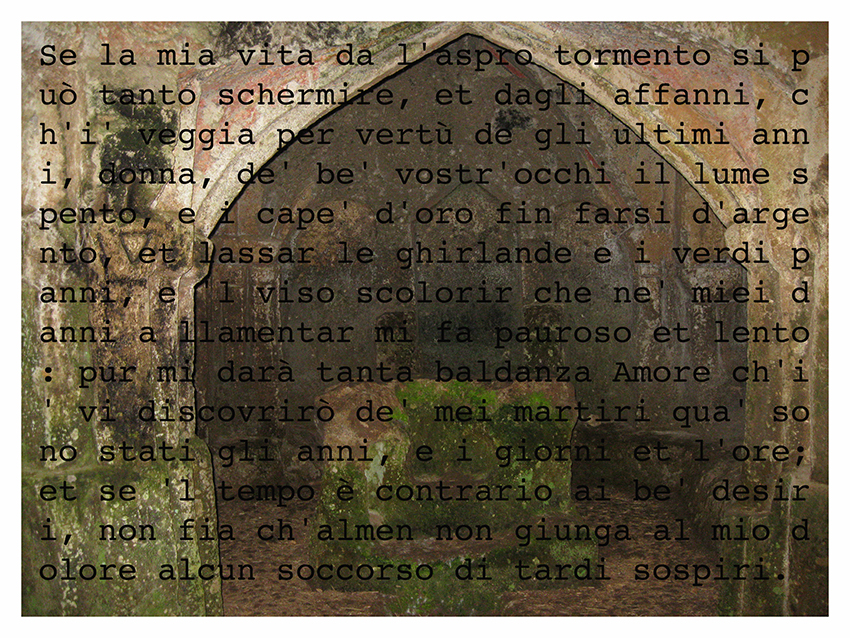

And what do these photographs have to do with the verses Dante penned to describe his entry into earthly paradise, the “ancient forest”, at the summit of the Mount of Purgatory, and his encounter with the beautiful and spiritual Matelda, guardian of the Terrestrial Paradise, where flowers bloom without being sown? Qui fu innocente l’umana radice; qui primavera sempre e ogni frutto… (Here the root of Humanity was innocent: here is everlasting Spring, and every fruit…). (5)

(09 Asiago 04, 10 Purgatorio XXVIII, 11 Nella selva 04)

Dante was certainly the last visitor to the Garden of Eden. No forest, not even the ancient forest that covered the volcanic formations of the Tuscia region in central Italy, can be considered primeval forest. In the Selva del Lamone natural reserve, for instance, traces of human “civilization” can be found everywhere: dilapidated walls, the remains of road pavement, the furrows of the charcoal wagons, the heaps of stones that once constituted Etruscan walls, and today the strips of white and red paint on the network of trails.

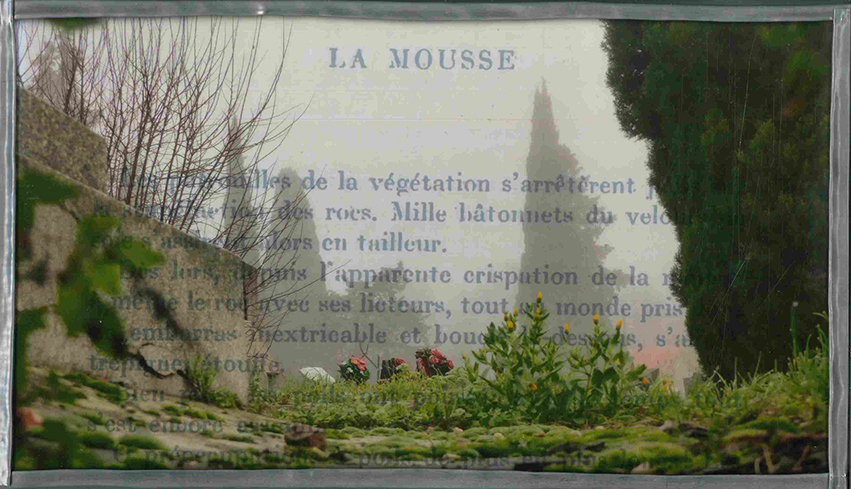

Today la Selva is a natural park, where the primeval has been reduced to reminiscences: trees, bushes, rocks covered by moss appear to me as Romantic artificial ruins.

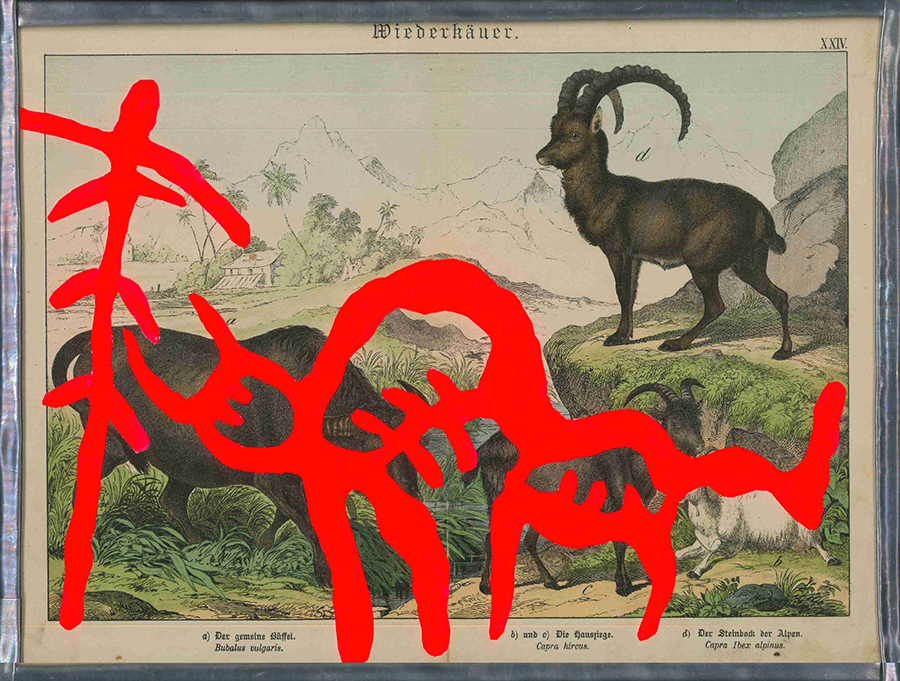

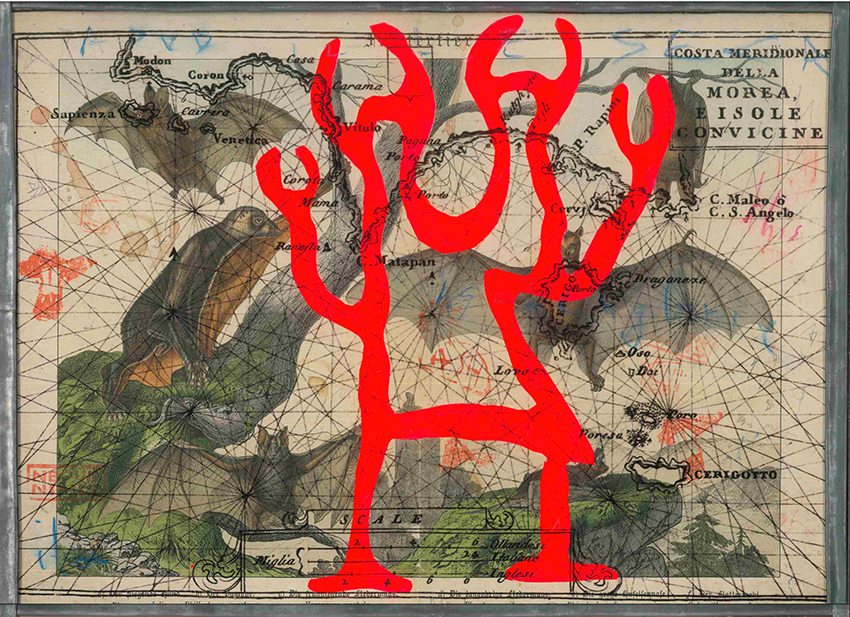

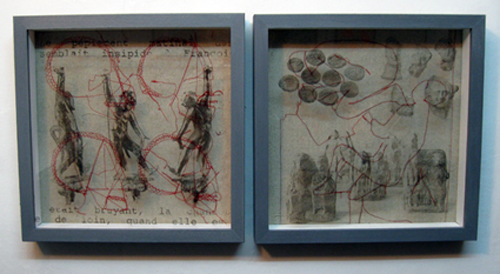

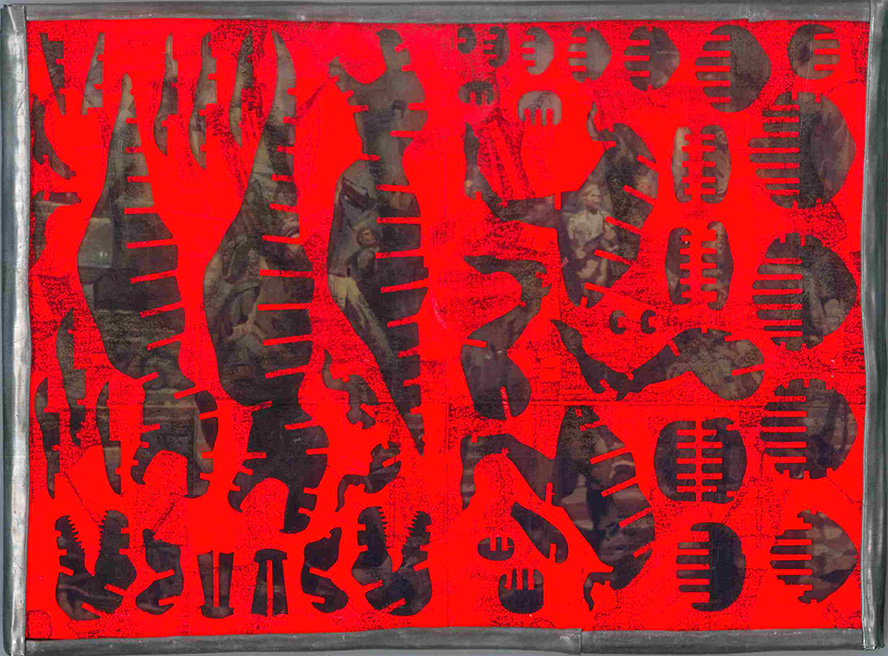

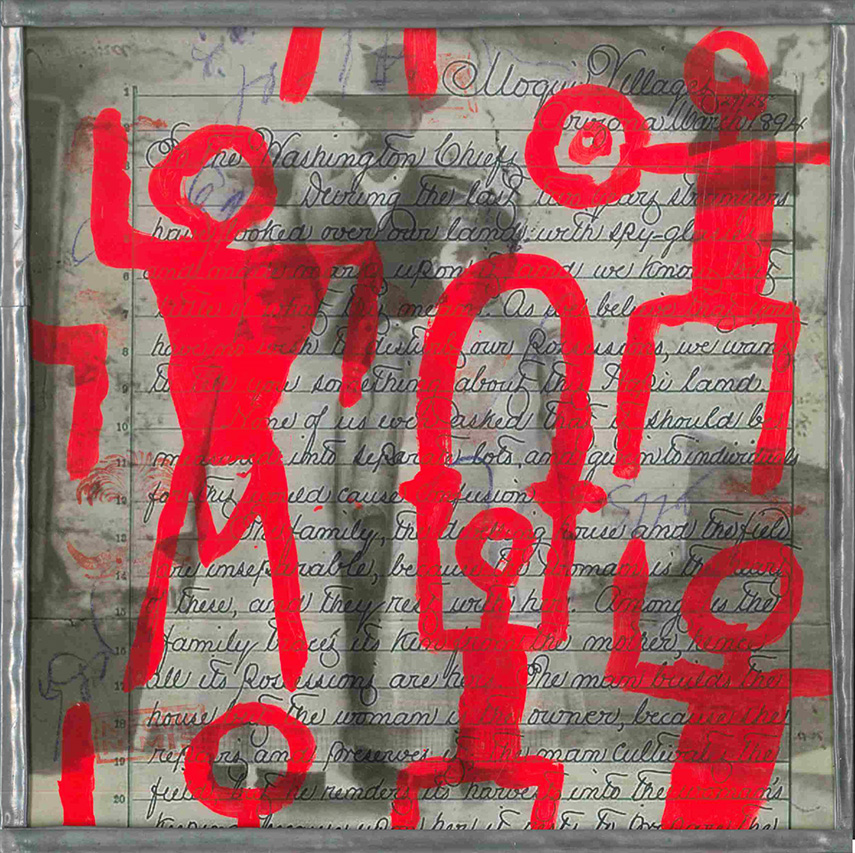

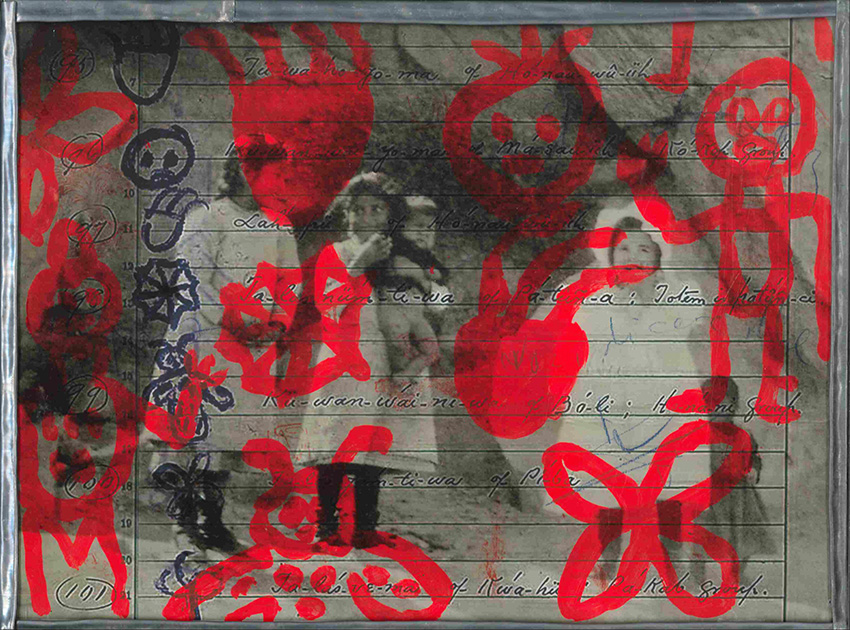

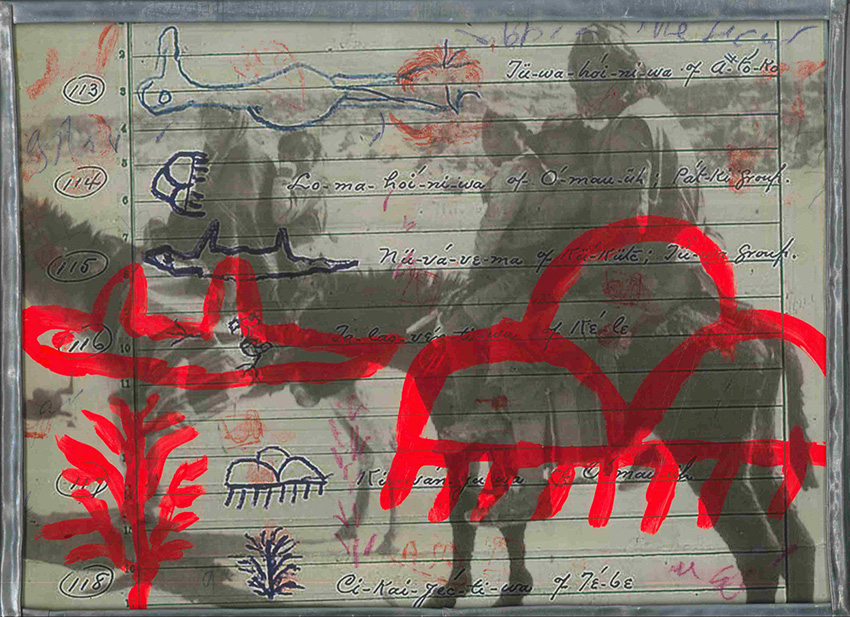

My photographs taken in the Selva are reproduced on transparent layers and superimposed on reproductions and personal variations of prehistoric petroglyphs; the images from Nevada dating back 10,000 years are the oldest discovered on the North American continent. They are the signs of an era when humankind was just beginning to appropriate nature. They are reproduced with red fluorescent acrylic paint, as a gesture of signage; the only difference with the petroglyphs being the technology used to reproduce the images. (12 Nella selva antica 06, 13 Nella selva antica 01)

Here you see a variation on this same subject, a series entitled Eden. My intention was to emphasize the relation to the theme of ruins within nature, a subject I will come back to later.

(14 Eden 04, 15 Eden 02)

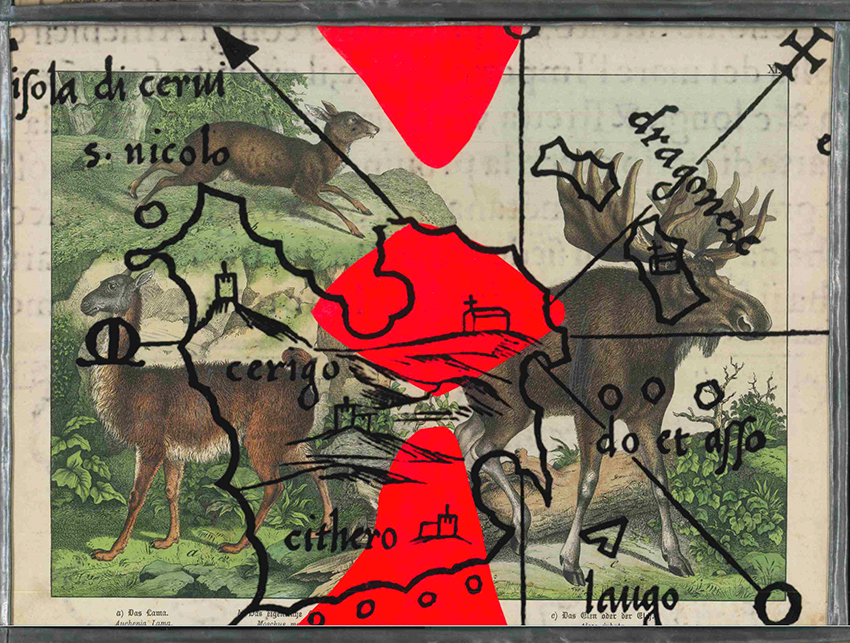

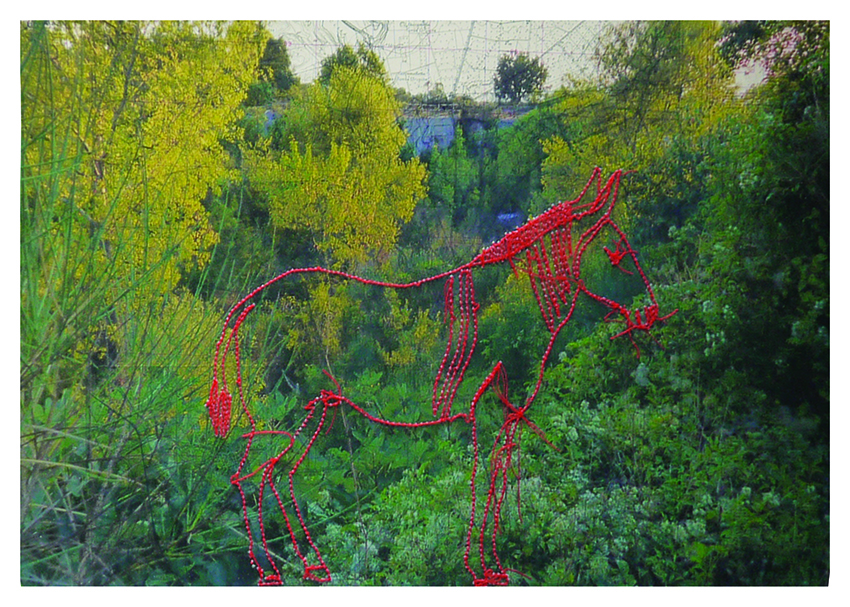

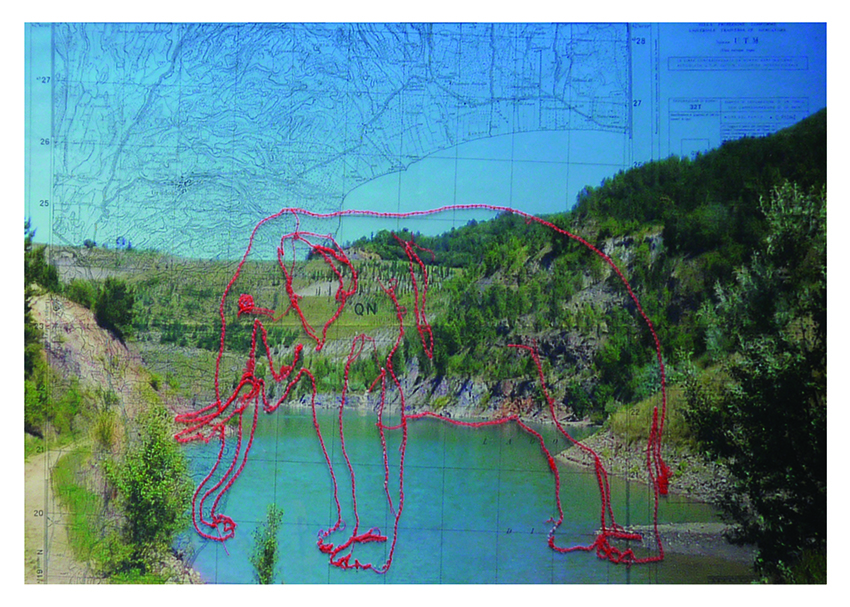

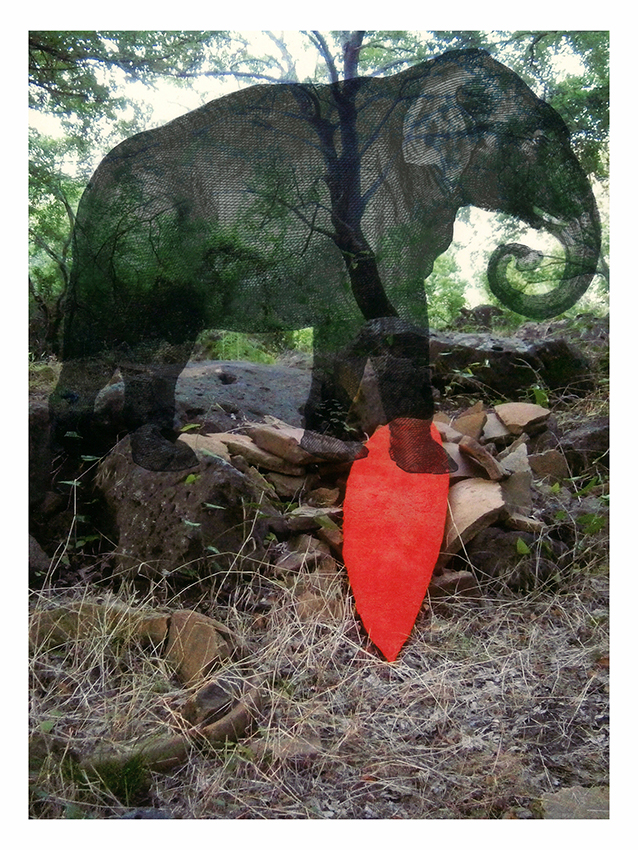

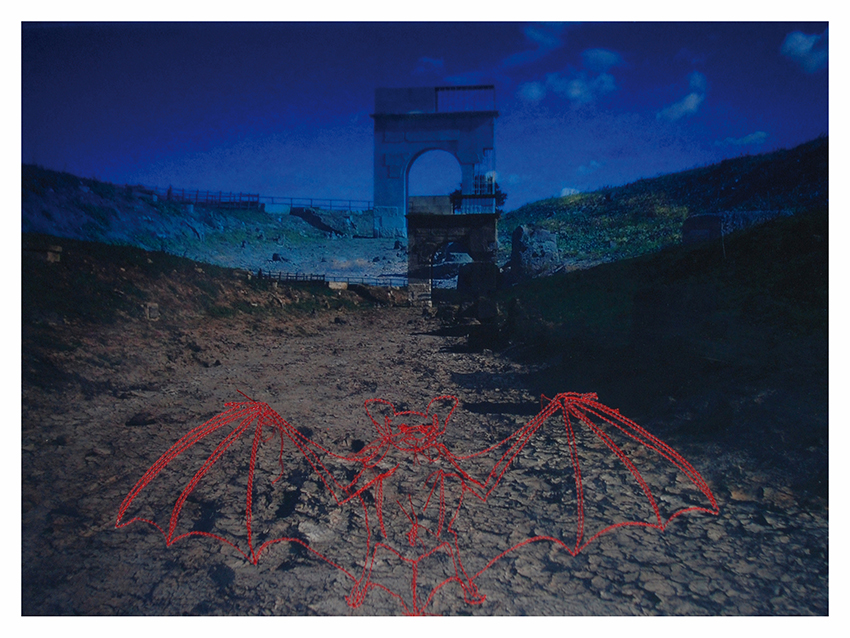

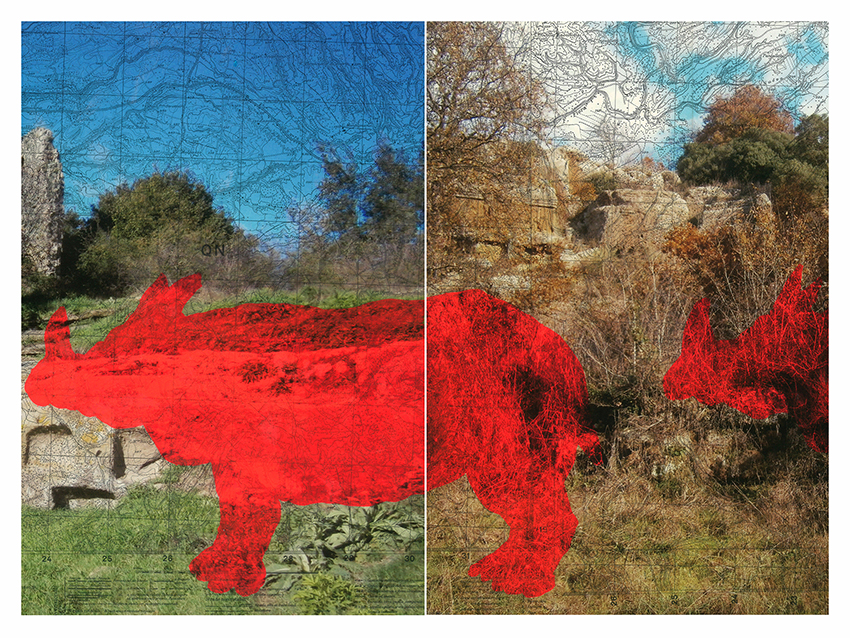

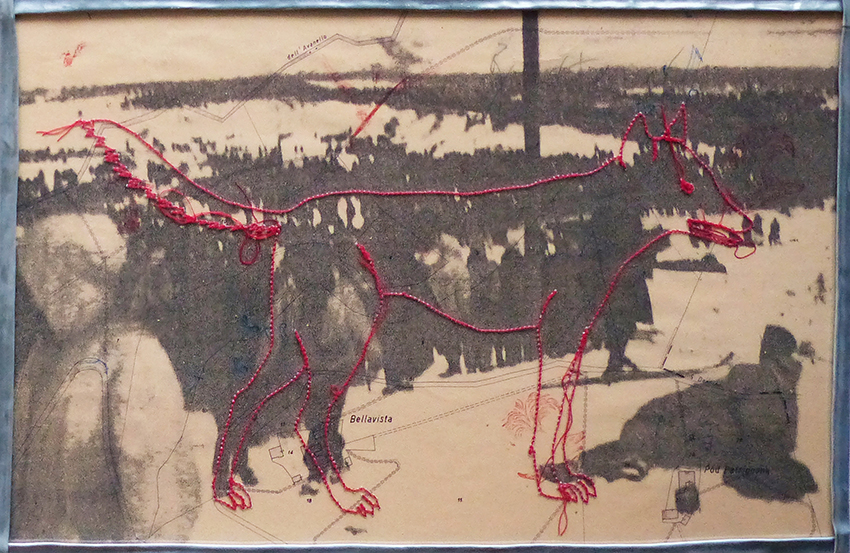

I added to my photograph a print taken from the plates of Georges-Louis Buffon Histoire naturelle, générale et particulière (second half of the 18th century), depicting wild animals. In his lifelong enterprise of describing quadrupeds and birds, creating a classification dependent on their degree of “sympathy” towards humankind, Buffon liked to set up those animals in a kind of state of innocence”. I extracted these illustrations from their original background to draw them on a transparent sheet with red thread so as to place them in an unexpected context.

(16 Buffon bull, 17 Vulci bat, 18 Land paintings 12)

I would like to go back to the interspaces between nature and civilisation, like I dealt with in a series entitled New landscapes. These recent works describe – not without an ironic reference to romantic landscape paintings – places where the border between natural and artificial is indistinct and unrecognizable – except perhaps only to the expert glance of the geologist or the botanist.

However it is certain that we do not know which of the two antagonists/ protagonists — humans or nature – precedes or follows the other. Nor do we know which will triumph in the end. But as the victory of one of them would mean the destruction of both, it would be preferable if they could be reconciled.

(19 PN 01 Vallerosa)

An abandoned travertine quarry, somewhere in central Italy. In the large cavity lined with white verticals walls, there developed a microclimate that gave rise to lush and varied plant life. Some say that, in spring, thirty varieties of wild orchids can be spotted. The site truly reverts to nature. It is even possible to encounter a large boar as you walk through the bush to reach the site. It happened to me, and I don’t who was more frightened: the boar darted in one direction, and I in the other.

(20 PN 02 Valentano)

A quarry of pozzolana (the red volcanic material used by ancient Romans to cover walls). As it evoked images of hell, it was used as the setting for some films depicting medieval times. After the quarry was abandoned, its terraces were replanted, but the young trees cannot conceal the regular patterns of the cuts in the hill. It is impossible to reach the site because a thick underbrush has overtaken the quarry’s floor.

(21 PN 03 Alès)

An artificial mountain, a terril, made of waste accumulated over years of exploitation of the coalmines, in the outskirts of the French city of Alès. It would have escaped everyone’s notice — except for the curious conic shape — had a forest fire in 2004 not burned all the vegetation leaving it bare. This fire, which is propagated through the roots of the pine trees planted to hide it, has reached the core of the hill, which continues to burn, slowly, impossible to extinguish.

(22 PN 04 Laval-Pradel)

An extensive open-air mine in the Cévennes region of France. It was exploited between the 1970s and the 1990s, and a historic road leading the Spanish pilgrimage site of Santiago de Compostela (the Chemin de Régordane) was diverted in order to accommodate the mining activities. After the mine was abandoned, three lakes formed (artificial or natural?) in the huge bulldozed spaces, and the national forestry authority is now replanting trees on site. The area is not accessible to the public and I entered the site illegally. The Alès municipality is considering transforming it into a recreation area. It would be a park for motorized sports such as quad, motocross, Jet Ski. In each of the three lakes a different species of fish would be introduced for the pleasure of fishermen. It will be another example of man-made nature.

.

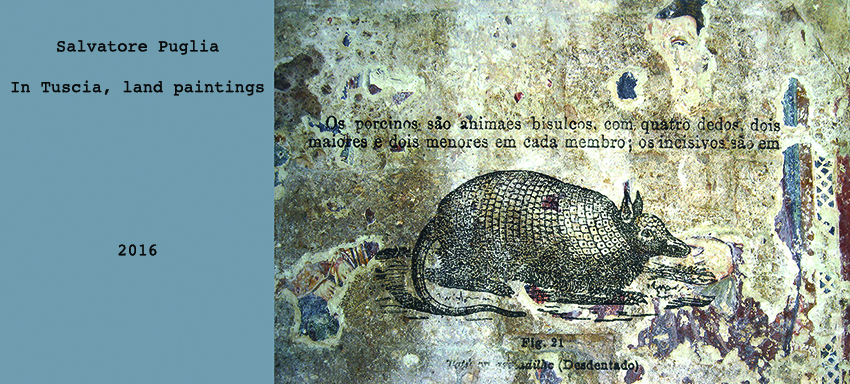

Chapter three: Land paintings.

(Images for Ruins in the island Chapter 3)

(01 Rupestri 00)

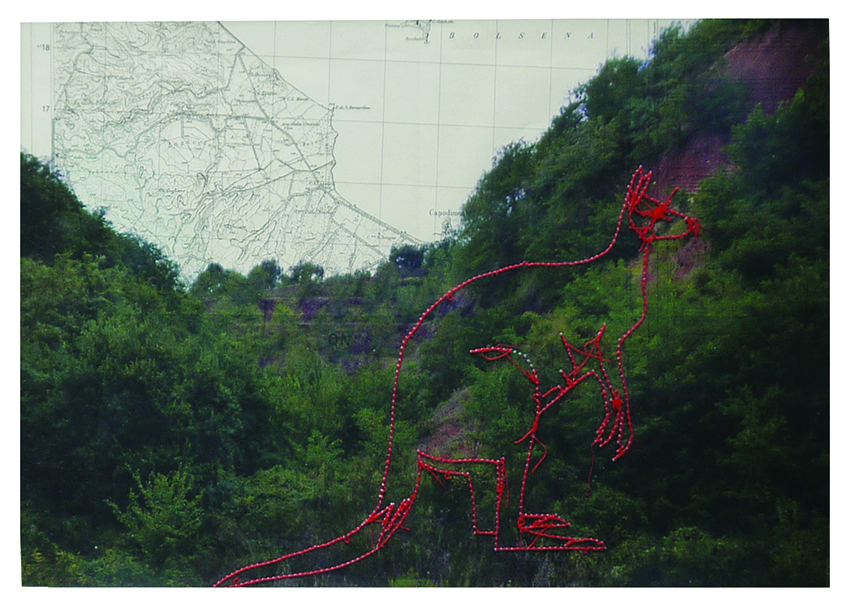

To me, this series represents an open and unresolved reflection on nature seen as a historical phenomenon, that I would qualify as “rupestrian ”.

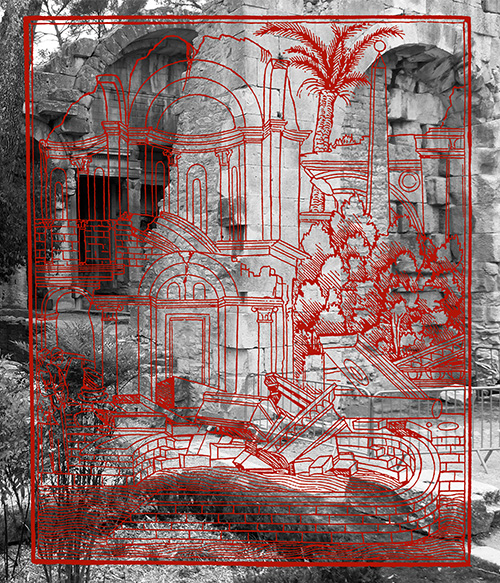

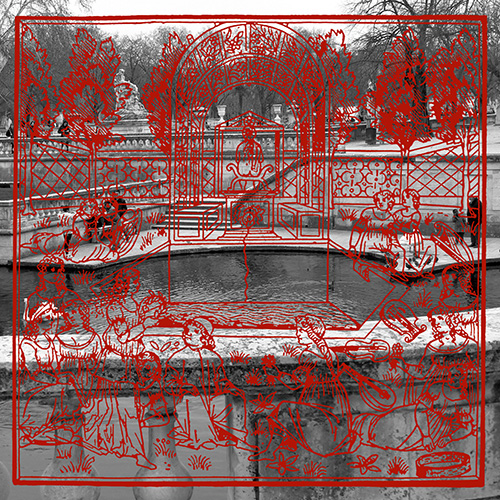

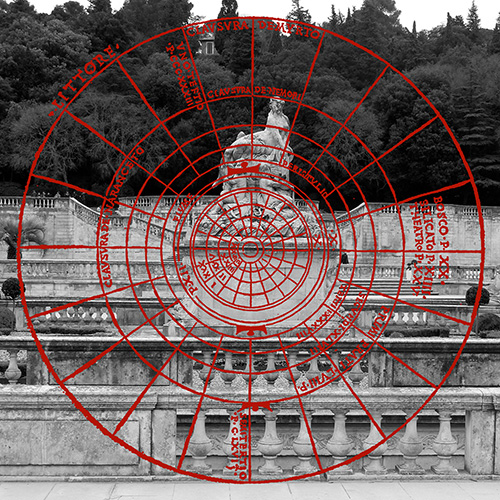

Although the term rupestrian denotes an art form ‘executed on or with rocks’ (e.g. tombs, sanctuaries, cave paintings or inscriptions), it can also refer to the process by which human-made creations fade away and become part of their surroundings.

In this sense, Rupestrian occurs at the meeting point of nature and history. In such instances, it is not only as if civilization and abandonment occurred in successive waves over the centuries; rather one was the pre-condition of the other. A natural site transformed into a “work” through human intervention is, in turn, retrieved by nature, which makes a “work” out of what remains of the initial human intervention. For me it is not so much about working horizontally in space (e.g. Land Art) as engaging vertically with time, which serves as a medium in a process of stratification ― a form of ‘reverse archaeology’.

(02-03-04-05 Santa Maria di Sala a-b-c-d)

In recent years, whenever I had the opportunity, I hiked around the Tuscia region, north of Rome, in a sparsely inhabited land full of prehistoric and archaeological sites, with a leaf, or a tongue, made out of latex dipped in red fluorescent pigment, leaving it on the ground, and then photographing it. During my hikes, I often stopped at the Etruscan tombs, which were used as medieval hermitages, then sheepfolds, then wartime shelters, and finally hideouts for lovers.

(06-07-08-09-10-11 Land paintings a-b-c-d-e-f)

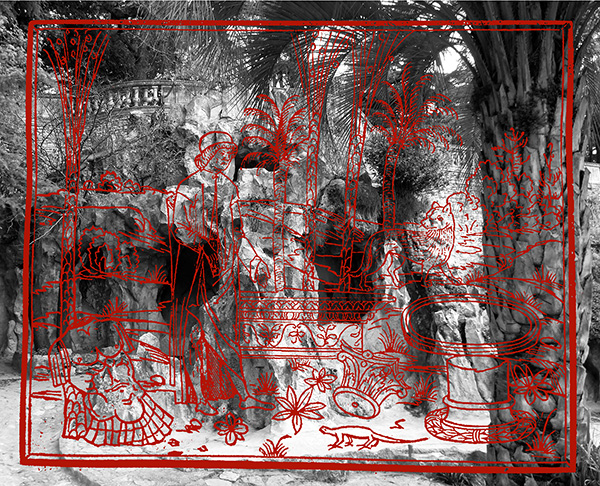

I entitled this photographic body of work “land paintings” partly as a reference to the notion of “picturesque” so dear to several land artists active in the 1960s and 1970, and in opposition to the modernist vision of a work of art seen as a unique, timeless experience, to be grasped in a single glance. The title is also meant to evoke the idea of stepping on earth, looking for hidden and forgotten places. It expresses a questioning about my own presence within historical space. Here I introduced myself, at dawn, in a “musealized” space like the Garden of Monsters in Bomarzo, created in the 16th century:

(12-13-14 Land paintings g-h-I, 15 Herbert List)

In my previous work, the sign placed on the photograph was a means of preventing the fruition of the image in its entirety, of opening up a gap of time within it, by using a fluorescent colour that displaced the vision. This intrusive element is now a material one and becomes an artwork as soon as the photograph is taken. This is the reason I do not usually add other semantic levels to it. Also, in contrast to Land Art, I do not transform the site in which I intervene: I simply leave a sign.

For a fleeting moment, I impose an artificial element to a “natural” landscape, like the footprint of a foreigner intruder. This sign left on the sites before photographing them constitutes a marker of my “I was there” but also a way of seizing the baton, in a relay race with the past. In my mother language the baton is called il testimone, which means “the witness”.

Going back to Panofsky, the “hard primitivism” of Piero di Cosimo can be seen as one of the two historical lines in the relationship between humankind and nature. According to Robert Harrison, there is, on one hand, an “antagonistic” line, marked by the Enlightenment idea of human progress “against” and “in spite of” nature; and, on the other end, a nostalgic, romantic view of a “natural” state of human purity. According to the latter line, the early days of humankind were not the “primitive form of existence as a truly bestial state” described by di Cosimo, but rather Dante’s earthly Paradise.

At the beginning of his book on forests, Harrison quote the Italian philosopher Giambattista Vico: “This was the order of human institutions: first the forests, after that the huts, then the villages, next the cities, and finally the academies…” (The New science, 1725). Vico goes on to write: “the nature of the peoples is such that first it is crude, afterward severe, then benign, later on delicate, eventually dissipate”.

Following Vico’s thoughts, Rigoni Stern assumes that the city (the last stage of human progress before academies, if one believes Vico) has become a place of “spiritual solitude”, where “barbarity dwells in the very hearth of the humans” and states that the wood has become a place of salvation (“Ed ecco che il bosco è diventato luogo di salvamento”) (6).

We can consider that Rigoni represents a form of “soft positivism” (i.e.: nature, in harmony with humans) will always triumph over the deadly enterprise that is war (and, I would even say, civilization). But in order to survive alongside nature, humans need to preserve the “environmental capital”, drawing only on the “interest”.

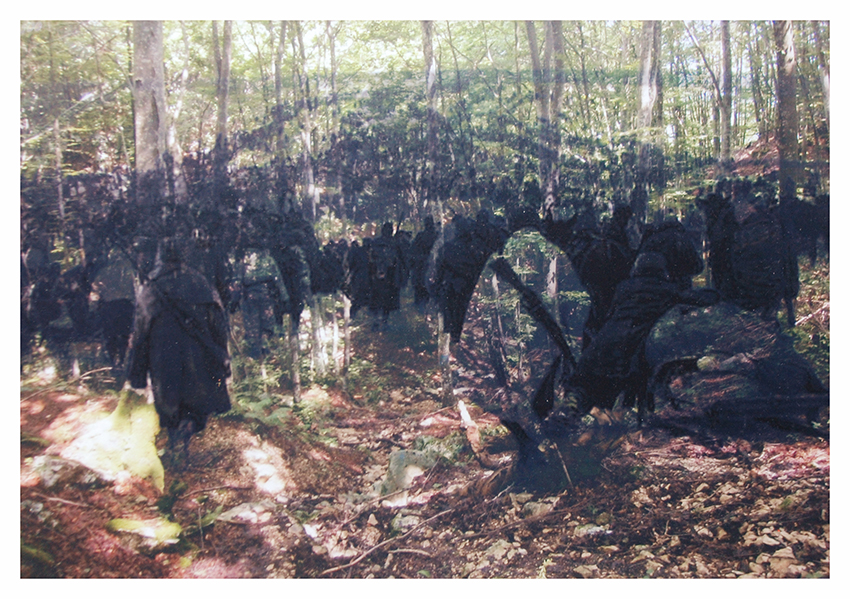

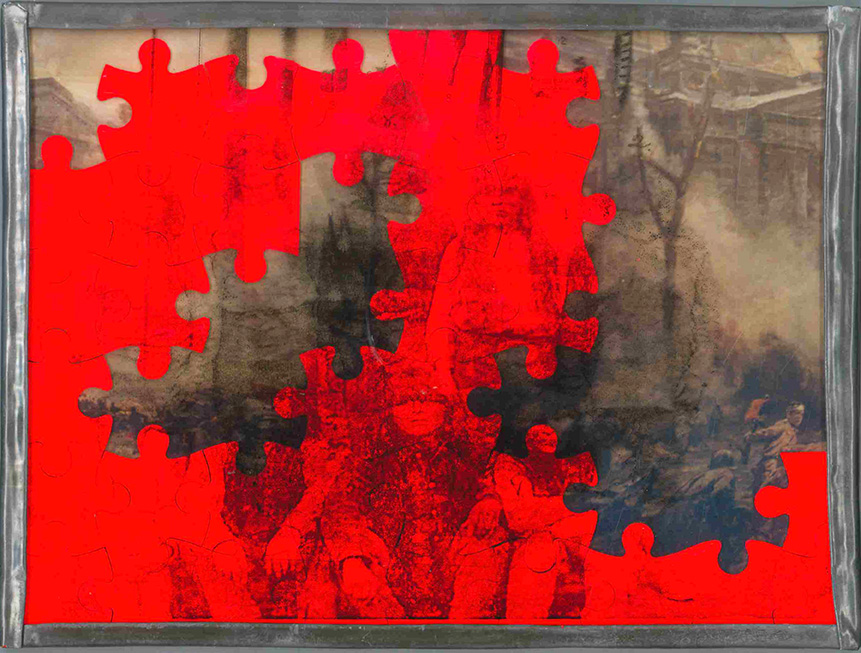

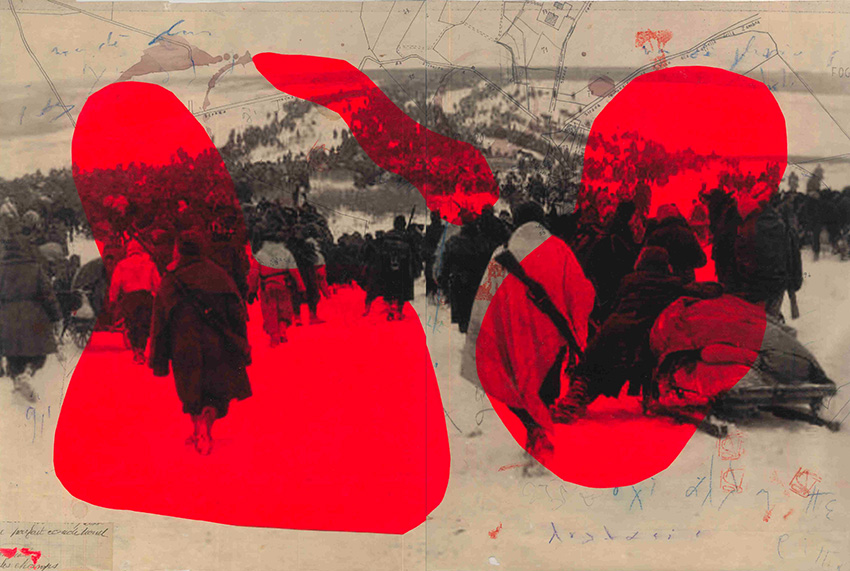

Here, an example of a work inspired by Rigoni Stern’s books; the “return to the heights”: Anabasis.

(16-17-18-19 Anabasis 03)

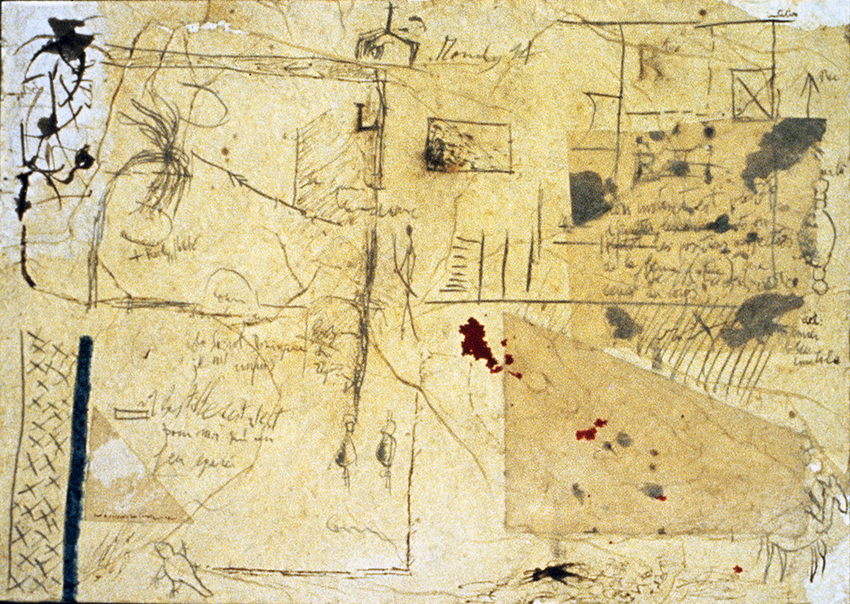

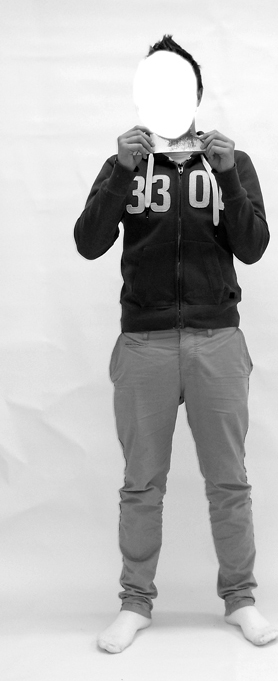

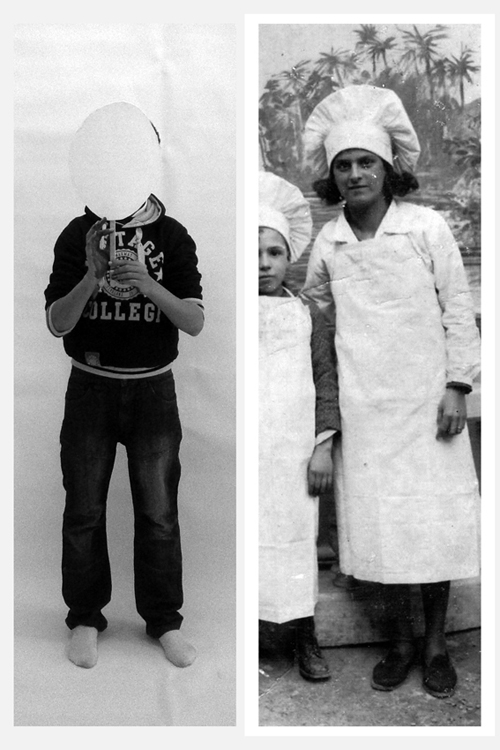

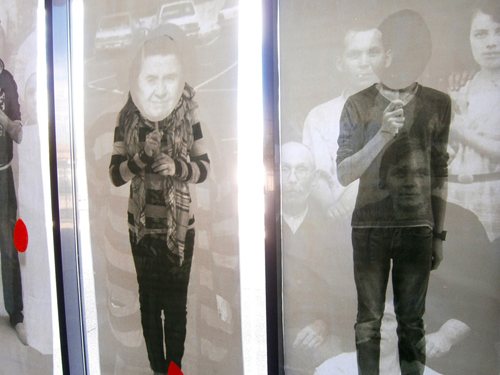

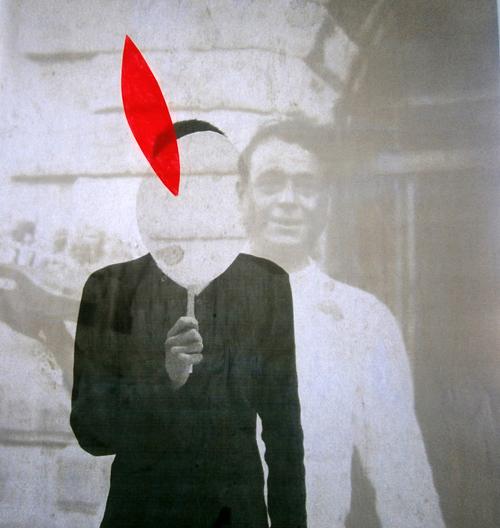

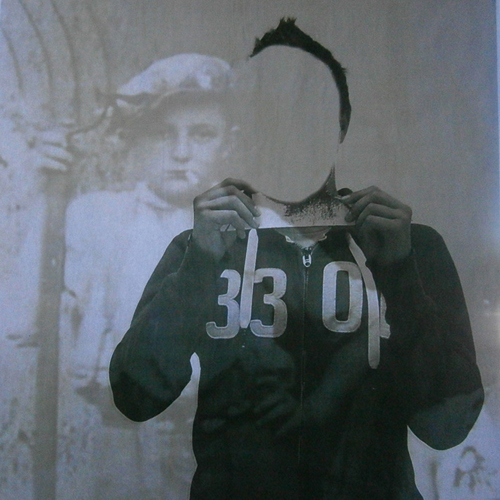

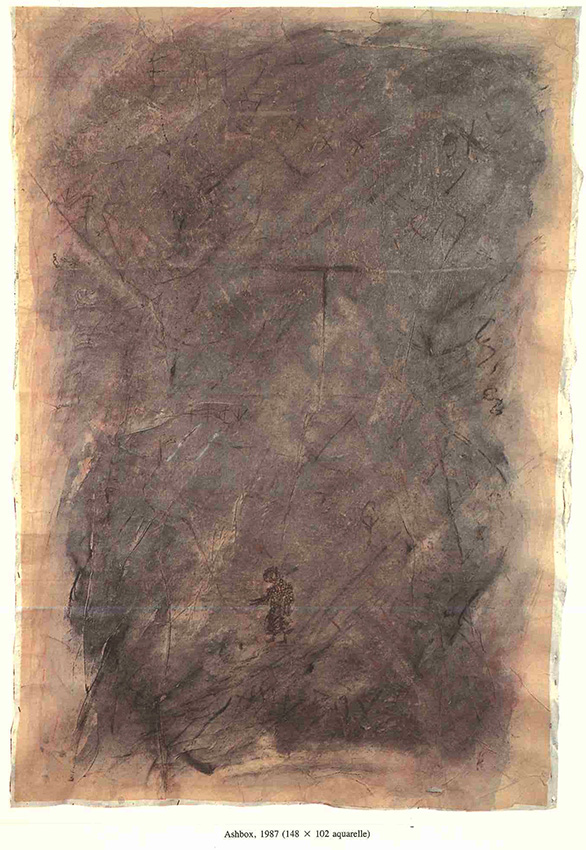

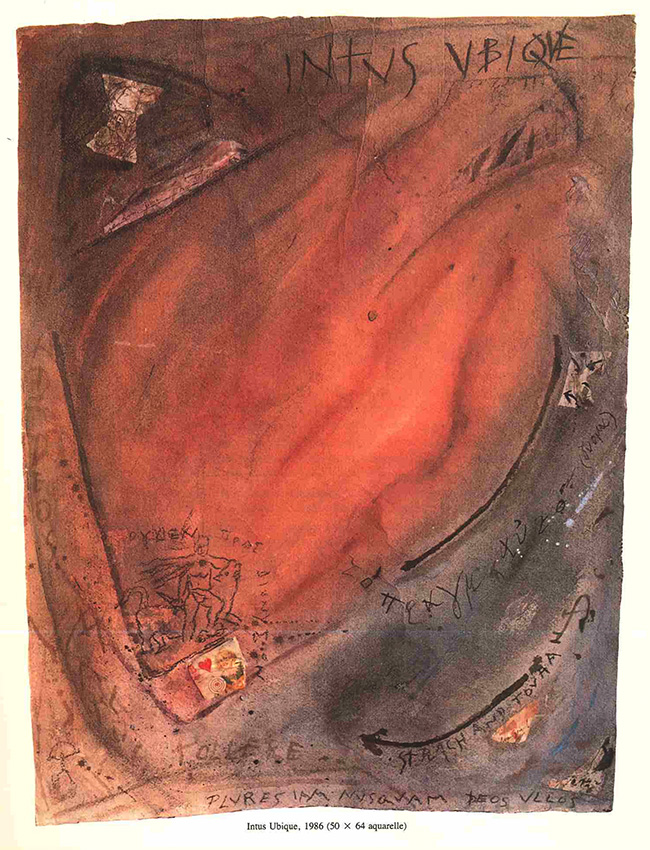

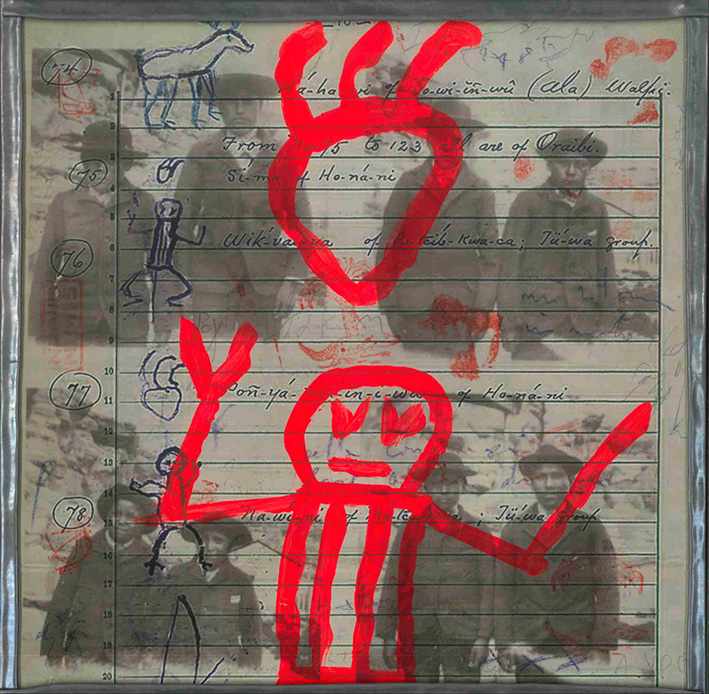

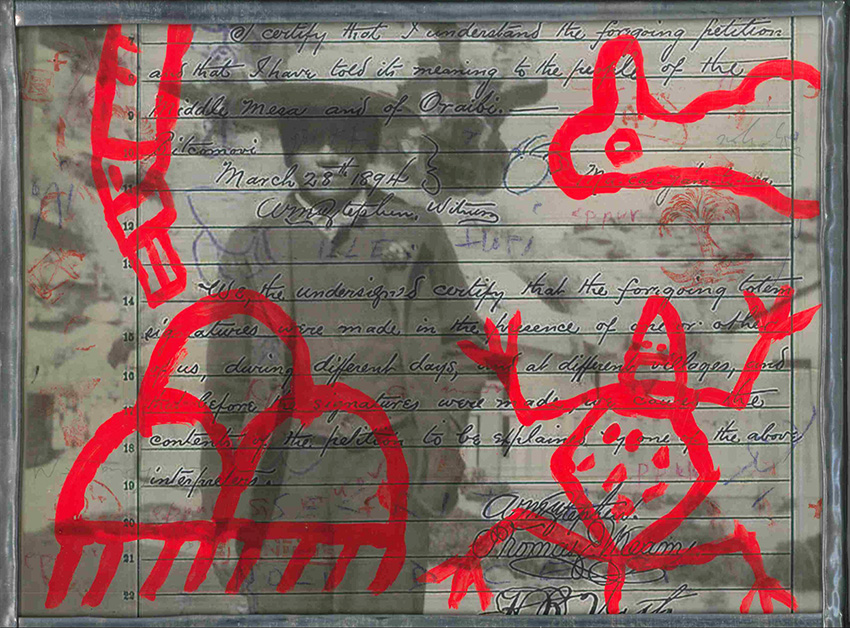

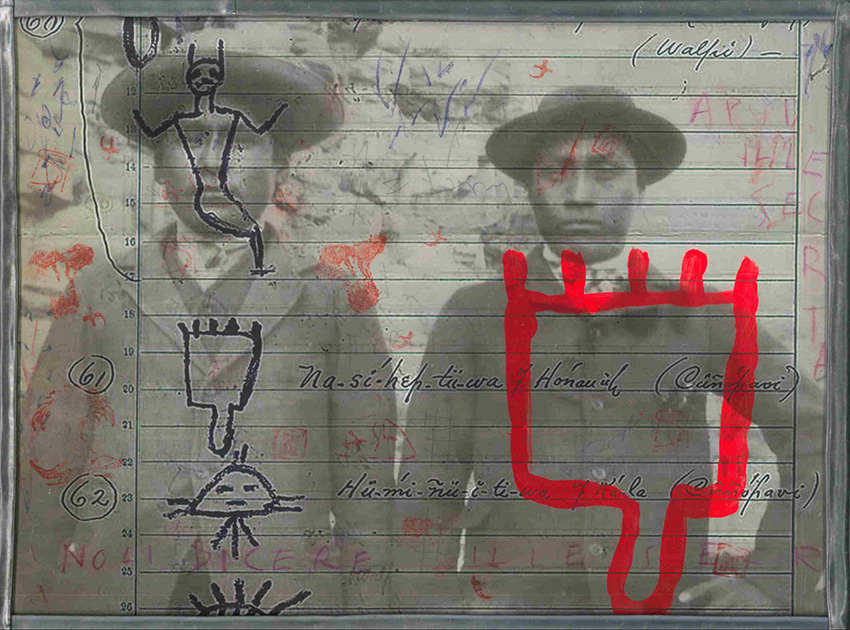

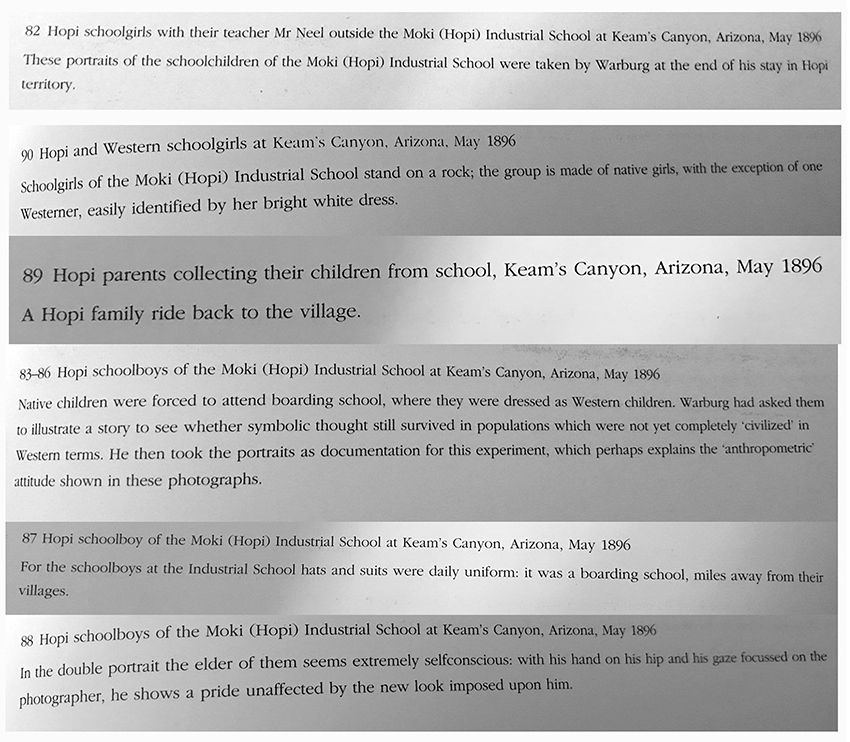

I am revealing to you the different steps of my procedure, which is at the same time an ideological commitment: to constantly affirm the multiplicity of any image, as well as of any individuality.

(20 Anabasis 06)

.

Chapter four: The call of the ruin.

(Images for Return to Cythera Chapter 4)

(01a, 01b, 01c Zeppelinfeld)

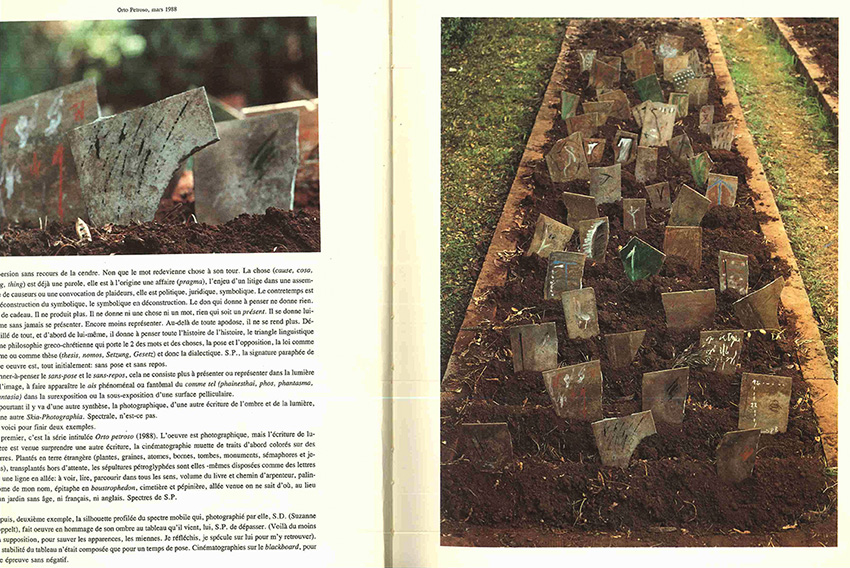

Or: Die Ruinenwerttheorie. Here we go from the ruins of Nature to the ruins of History, and I will begin with a long quote from the writings of Hitler’s chief architect, Albert Speer:

“In this context I should perhaps dedicate a few words to the so-called Theory of Ruin Value, which is not Hitler’s. It is my own theory!

As a commentary to Speer’s remarks, it is perhaps interesting to remember that the Zeppelinfeld stadium “the world’s largest tribune,” which welcomed 100,000 members of his Party is – although it has been divested of the most evident marks of its original function such as the colonnades and giant eagle – today a recreational park where both car racing and open-air rock concerts take place.

Indeed comparison, what interests me in Speer’s discourse is the relationship between ruin and monument. The monument always has a finger pointing somewhere; it always indicates a direction in time, even if it is there for remembering (Denkmal in German) or for admonishing (Mahnmal). As Leopardi already noted, in the middle of the Romantic period (in his Zibaldone di pensieri), one builds a monument to counter the idea of finitude.

I find it interesting to reflect on how a regime at the height of its power can already be interested in the forms of its own demise. For my part, I am attracted to “unconscious” ruins. The images used for the work Antiquarium were mainly taken in two places: 1) in Rome, in the Antiquarium comunale of Celio, a veritable open cemetery for archaeological relics that – too fragmentary, dispersed or anonymous – didn’t even find a home in some museum warehouse; 2) in Bagnoli, near Naples, in the disaffected or soon to be demolished industrial buildings of the Italsider.

(02 Antiquarium, 03 Thesis two, 04 Bagnoli, 05 Thesis two)

These piles of rubble are supposedly the antithesis of what Hitler and Speer intended by “ruin value.” At the same time, I am not sure that what made me scale the fences surrounding these sites in order to photograph them was not a version, perhaps more conscious or more “de-constructed,” of a similar attraction for the ruin in and of itself. Of course, this was not the pathetic nostalgia for a Mediterranean world that took pride in an ancient history and a monumental past, a form of nostalgia that incited many European aristocrats to construct artificial ruins of painted wood and plaster in the parks of their castles.

But this fascination for romantic ruins, quite obvious in Speer’s text, and which comes directly from the 18th century, is typical for rational beings who gamble their own persistence in future time. In short, Speer’s concept seems to me a perfect syncretism of Enlightenment and Romanticism.

As I was born in Rome, I was familiar with the remains of Antiquity disseminated in the most usual places, public gardens and courtyards in the Renaissance buildings of the city centre.

(06 From Orvieto, 07 Antiquarium postcards, 08 Antiquarium replay 09 In Tuscia 06)

Then I went to Germany in my quest of artificial ruins, the Künstliche Ruine: I went to Potsdam, in the parks where the Kings of Prussia built their own form of identification with classical antiquity.

When I photographed the Norman tower site in the Sanssouci park, with its “Roman” arcades and “Greek” temple (this was in 2003), I found it quite amusing that it was in the process of being restored to its “original fakeness.”

(10 Normannischerturm, 11-12-13 Eine Künstlische Ruine)

As an aside, I’d like to show you several images illustrating the aesthetics of the ruin. It seems to me that all of them, in their diversity, constitute ain a linear vision of time: these are “pre-Benjaminian” images. The fall is not yet the catastrophe, and there will be no caesura in time (I am thinking of Walter Benjamin’s famous text on a watercolour by Paul Klee entitled Angelus Novus. The angel of history is inexorably pushed into the future, while looking towards the past, where “the pile of debris before him grows to the sky” (to quote his ninth Thesis on the Philosophy of History, written in early 1940).

(13a Serlio) Frontispiece of Book V of the Architettura, by Sebastiano Serlio, dated 1544. The Latin text on the front page reads: “its own ruin demonstrates how great Rome was”.

From the Renaissance a direct line leads us to Baroque and Enlightenment age:

(14 Capriccio di rovine) Caprice of Ruins, Giovambattista Piranesi, 1756. Please note the size of the characters in relation to that of the piled-up vestiges.

(15 Rovine di una galleria di statue nella Villa Adriana) Ruins in a Statue Gallery in Hadrian’s Villa, Piranesi, finished in 1770.

(16) The Artist’s Despair before the Grandeur of Ancient Ruins, Johann Heinrich Füssli, 1780.

(17) View of the Grand Gallery of the Louvre in Ruins, Hubert Robert. This enlightened and learned artist, projects himself into the future while actively participating in the acquisitions and construction of the new Louvre Museum around 1795.

(18) A Bird’s-eye View of the Bank of England, Joseph Michael Gandy, 1830. This watercolour represents an imaginary stage of the building designed by Sir Albert Soane and not yet finished; on the same time, it allows a vision of its interior as “both seemingly in ruins and under construction”.

(19 Pfaueninsel map)

I don’t know why islands and ruins often appear together in Romantic imaginary. Here are a few images of Pfaueninsel, the “Peacock Island” located in the outskirts of Berlin, which can be considered a complete “artificial ruin”.

(20 tempio dorico)

Pfaueninsel was acquired by Frederick William II of Prussia in 1793 and was initially used as a hunting reserve. Before the end of the 18th century, Brendel, the court carpenter, had already erected two buildings in the form of ruins: the castle, whose south-facing façade welcomed the visitors from Potsdam and Sanssouci residence; and a Gothic-style farm on the other side of the island.

Let’s stroll through the well-rutted lanes, without smoking or trampling on the lawns, as the billboards say: “We ask you to stay on the paths and observe the smoking ban”. Let’s rather admire the geometric configuration of the buildings half-hidden by the leaves, veiled in the distance by the mists, but still visible from each vantage point: the Doric temple, the Alexandrian ruin, the Scottish castle and Schinkel Kavalierhaus, whose medieval tower was built from the remains of a Gothic house in Gdansk.

(21 Cavalierhaus, 22 castle 23 ruin)

(24 Pfaueninsel temple)

.

Chapter five: Nerval’s Neverland.

(Images for Return to Cythera Chapter 5)

And here, at last, we come to Greece (01 Chabas).

This oil on canvas, executed by the French painter Maurice Chabas in 1896, about one hundred years after the creation of Pfaueninsel, represents a place that everybody knows, but that very few have visited: the Greek island of Cythera. What is surprising to me is not the somehow idealized and sentimental representation of the cult of Aphrodite, but the fact that it was created not long after the works of Gérard de Nerval and Charles Baudelaire, which demystified the Romantic image of the island.

It is true that the times were ripe for a different representation of Aphrodite’s birthplace, and not necessarily for the best: here you have a linocut print by Louis Métivet, a well-known illustrator and cover artist for the magazine Le rire: this “Zurück von Kyhtera” was published in the German magazine Moderne Kunst around 1900. (02 Métivet)

The “girls from Cythera” are represented in an unflattering manner. It was the time of the “Suffragettes” movement for women’s rights, and this image is clearly directed against them. It is evident as well that Métivet goddess’s kingdom is not the same as the one depicted by the Symbolist Chabas: to express it bluntly, it is a brothel.

As you know, Cythera, considered to be Aphrodite’s homeland, was a mythical place, the subject of endless allegorical representations in literature and the arts. Born from the sea waves, and brought to the land, surfing a huge shell pushed by Zephyrus breath, Aphrodite was the worshipped goddess of lovers.

But what did Baudelaire and Nerval write about Cythera?

Baudelaire, in his poem “Voyage à Cythère”, published in 1855 in Les fleurs du mal:

Free as a bird and joyfully my heart Soared up among the rigging, in and out; Under a cloudless sky the ship rolled on Like an angel drunk with brilliant sun. “That dark, grim island there—which would that be?” “Cythera,” we’re told, “the legendary isle Old bachelors tell stories of and smile. There’s really not much to it, you can see.” O place of many a mystic sacrament! Archaic Aphrodite’s splendid shade Lingers above your waters like a scent Infusing spirits with an amorous mood. Worshipped from of old by every nation, Myrtle-green isle, where each new bud discloses Sighs of souls in loving adoration Breathing like incense from a bank of roses Or like a dove roo-cooing endlessly . . . No; Cythera was a poor infertile rock, A stony desert harrowed by the shriek Of gulls. And yet there was something to see: This was no temple deep in flowers and trees With a young priestess moving to and fro, Her body heated by a secret glow, Her robe half-opening to every breeze; But coasting nearer, close enough to land To scatter flocks of birds as we passed by, We saw a tall cypress-shaped thing at hand— A triple gibbet black against the sky. Ferocious birds, each perched on its own meal, (…)

Baudelaire’s images and metaphors are directly inspired (as he recognizes) by Gérard de Nerval Voyage en Orient, a series of articles collected and published in 1851.

In 1843, Nerval travelled extensively to the Middle East, spending months in Egypt, Lebanon and Turkey. The account of his experiences is truly poetic; it is a mixture of things witnessed first-hand, dreamlike descriptions, and plagiarizing texts by other authors.

(03 steamer route)

To reach Alexandria, he took a ship from the French port of Marseilles, but he claims to have sailed from Trieste on the Adriatic Sea. Surely, he was in Malta and from there to the Greek island of Syros. He might have actually seen Cythera. He describes the spectacular sighting of the island at dawn: I have seen it that way, I have seen it: my day began like a Homeric verse! It really was the rosy-fingered dawn that opened the gates to the Orient for me. He confesses that he was searching for ‘Watteau’s shepherds and shepherdesses, their garland-adorned boats approaching flowered banks. (04 Watteau Cythère)

But he appears to be deeply disappointed (or, rather, he feigns great disappointment): Here is my dream… and here is my awakening! The sky and the sea are still present; every morning the Eastern sky and the Ionian Sea lovingly kiss; but the earth is dead, killed by the hands of humankind, and the gods have taken flight. (…)

(05 Komponada beach)

As we were sailing along the coast, before taking shelter at San Nicolò, I noticed a small monument, whose silhouette was barely perceptible from the blue sky …… and from its perch atop a rock resembled a still-standing statue of some tutelary deity. But as we approached, we were able to discern very clearly this landmark. It was a gibbet, with three arms, only one of which was adorned. The first genuine gibbet that I had ever seen; it was on Cythera, a British protectorate, that I was able to spot it!

Gérald de Nerval never set foot on Cythera, or Cerigo, as it was known under Venetian rule. It is likely that he skirted the island in his French postal steamship on route from Malta to Alexandria via Syros. But he never landed on the island, nor searched the remains of the Aphrodite temple, nor visited a necropolis or a grotto by the sea.

Also the triple gibbet, that Nerval describes in order to stigmatize the British occupation of several Greek islands, is probably a literary invention. And his description of Cythera owes much to two travel guides: Voyage en Grèce by Dimo and Nicolo Stephanopoli, published in London the year 1800; and Antoine-Laurent Castellan’s Lettres sur la Morée, published in Paris in 1808 (7).

Nerval mentioned having seen, in a bucolic landscape near the Aplunori hill, a marble stele, which bore the words: “heart’s healing”. He was no doubt inspired by prints produced by Stephanopoli and Castellan (8).

(06 Stephanopoli view, 07 Stephanopoli inscription, 08-09-10 Castellan views)

As he stated, Nerval had in mind two references, during his travels around the Mediterranean: a painting, Watteau’s Pilgrimage to Cythera, and a literary work, Francesco Colonna’s Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, better known in French as Le songe de Poliphile and first translated in English under the title Poliphilo’s Strife of Love in a Dream.

Watteau’s painting was presented at the French Academy of Arts in 1717, earning him, by royal appointment, the creation of a new section in the establishment, the genre “fête galante”. Before him, the only category worthy of a prize was the genre known as “peinture d’histoire”. (10a Watteau detail)

Nerval was an admirer of Watteau’s depiction of fleeting beauty and pleasure. In the novel, Sylvie, published in 1853, he sets a party scene in a park, near the village of Ermenonville in the northern outskirts of Paris. It reminded him of Watteau’s paintings depicting Cythera, and Jean Jacques Rousseau presence there (Rousseau’s ashes remained for some years in a tomb designed by Hubert Robert, in a small island in the middle of the park). Nerval mentions also the Temple of Philosophy (which was unfinished, according to the wishes of its creator, the Marquis de Girardin). This is another example of 18th-century “imitation ruins”, its model being the Temple of the Sybil in Tivoli. René Louis de Girardin, Rousseau’s close friend and sponsor, was the author of a remarkable treatise De la composition des paysages, (The composition of landscapes) published in 1777.

(11, 12 Temple philosophie)

Now we come to the second work that served to guide the French poet in his travels to never-never land Cythera.

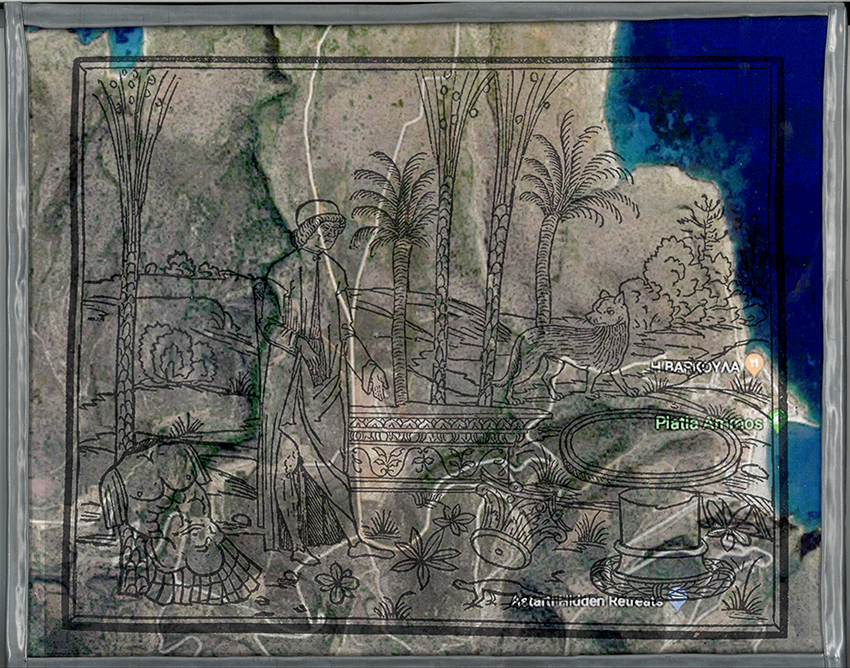

(13 Hypneroto gardens)

Le songe de Poliphile is an extremely learned and obscure compendium of the Renaissance view of antiquity. Between the 16th and 18th centuries, the work was rather influential, among poets, painters, architects and garden designers. The recent bestselling novel, The Rule of Four by Ian Caldwell and Dustin Thomason, as well as the installations of some contemporary artists (Nicolas Buffe, Sophie Dupont, Paolo Bottarelli), take inspiration from Colonna’s Hypnerotomachia.

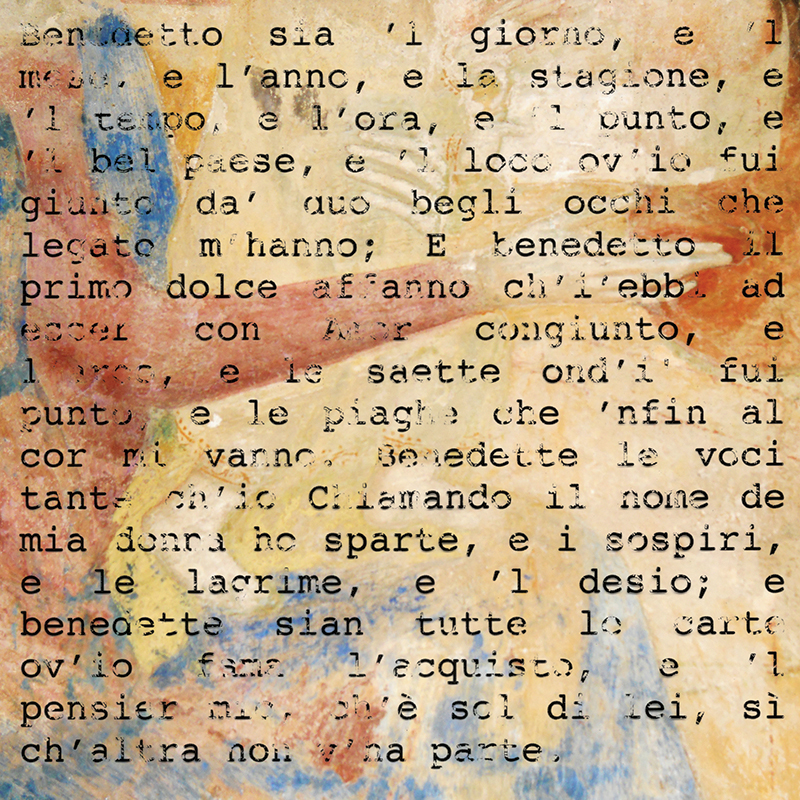

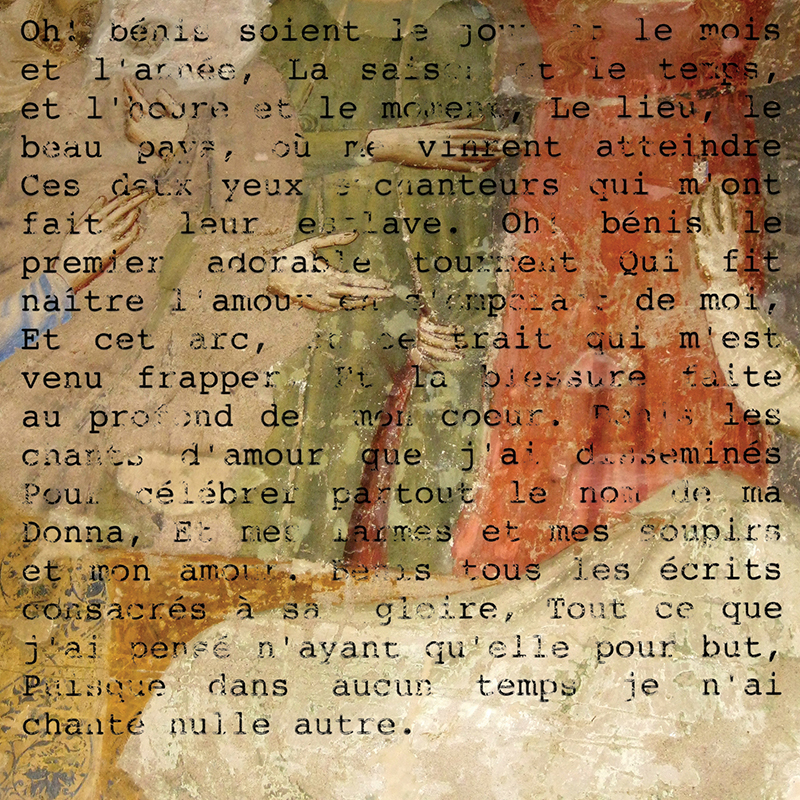

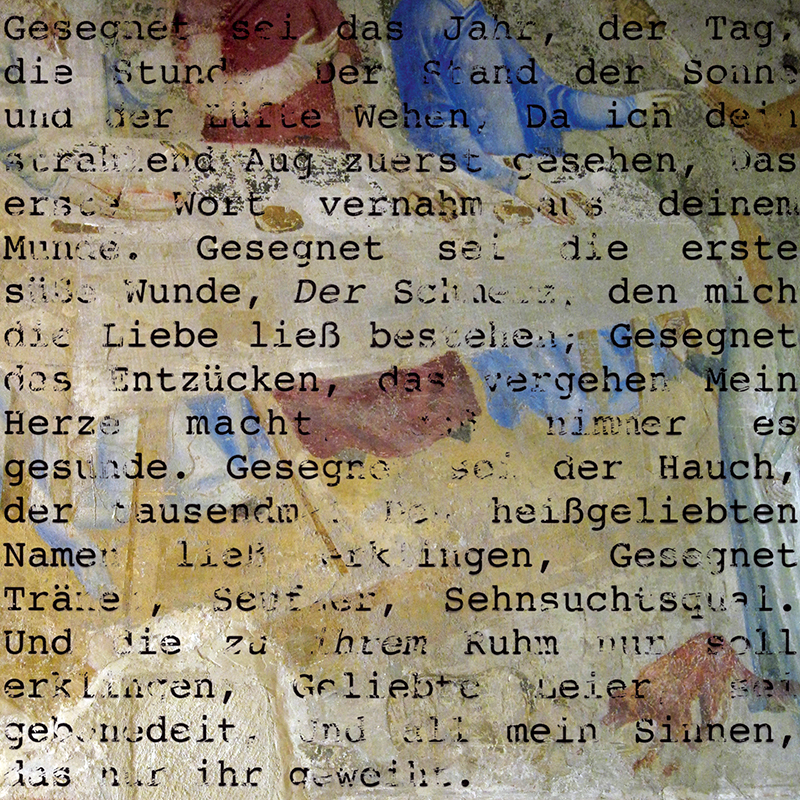

Presumably completed in 1467 and published in Venice in December 1499 by the great printer Aldo Manuzio, it was written in an inventive language, consisting of spoken Italian mixed with Latin and Greek with Arabic and Hebrew inclusions. It is very likely that the Italian humanist Leon Battista Alberti assisted in its conception. Its complete title in English would read: The Sleep-Love-Fight of Polifilo, in Which it is Shown that all Human Things are but a Dream, and Many Other Things Worthy of Knowledge and Memory.

(13a Incipit)

The love story between Poliphilo and Polia, conceived as a series of intertwined dreams, serves as a pretext (only one tenth of the book’s 234 pages are devoted to this narrative plot) to a kind of encyclopaedia of the period’s knowledge of antiquity as concerns rituals, costumes and accessories, as well as architecture, botany, gardening, landscape architecture.

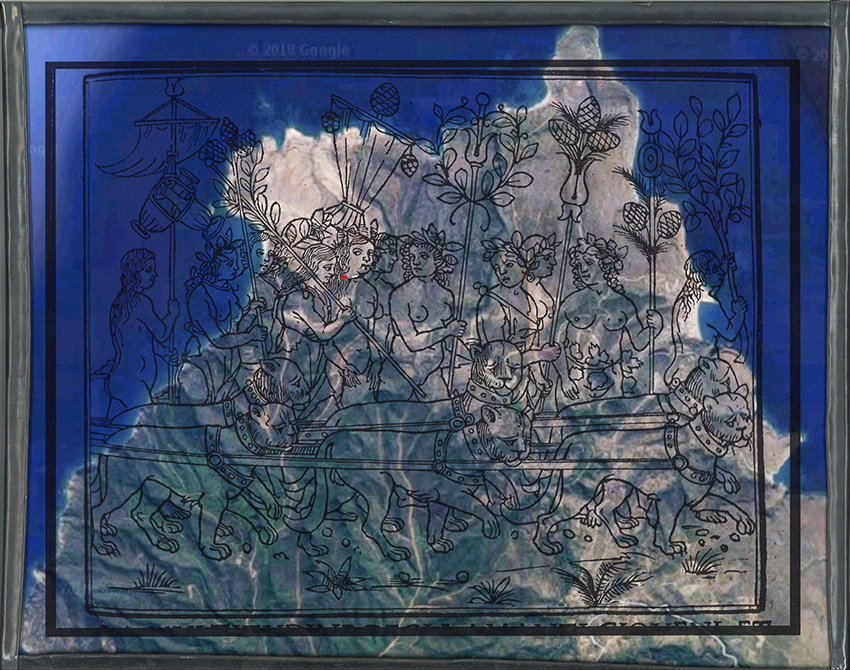

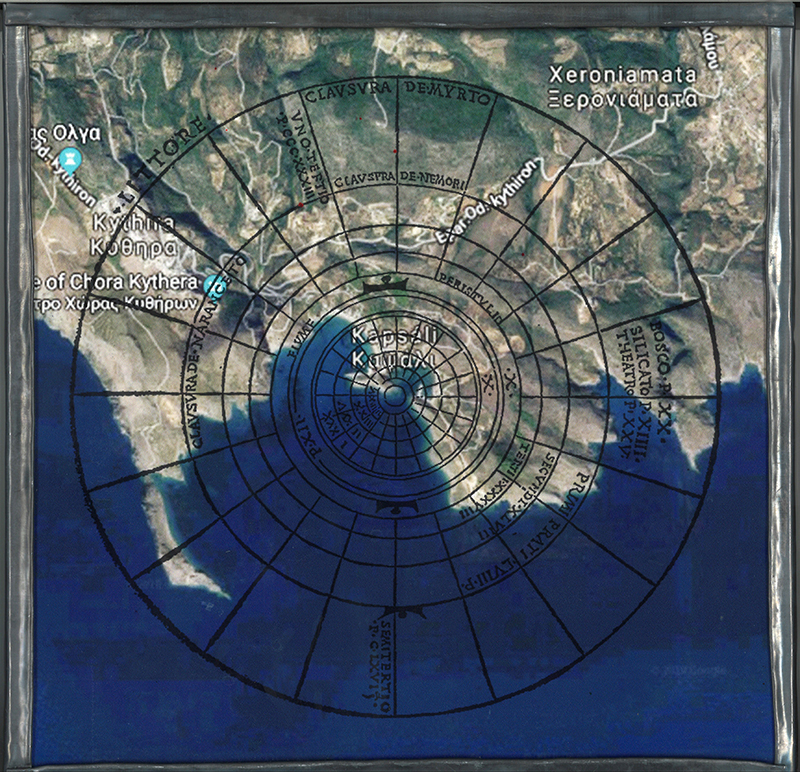

Much of the action described in the book takes place on the island of Cythera. It is there that the two protagonists celebrate their wedding, and Aphrodite appears to them. It is also on Cythera that magnificent and intricate gardens are described, along with ancient ruins and monuments and ceremonials.

The book is illustrated with 172 magnificent woodcuts by an unknown artist. But it is not known which Francesco Colonna is the author: the learned friar from Treviso, or the Lord of Palestrina? Some experts have even proposed that Colonna might be a pseudonym for Leon Battista Alberti himself (9). Surely, the text cannot be read without the help of the images, and the images cannot be fully appreciated without understanding the text.

(14 Hypnerotomachia acrostic, 15 wolf, 16 torture, 17 triumph)

The subject of the archaeological, classical ruin is quite present in this book. It corresponds to a zeitgeist, particularly present in the Venice area, as Andrea Mantegna’s activity bears witness to. Some experts credit this painter as the creator of Poliphilo’s woodcuts. Here are a couple of details from his Saint Sebastian, painted around 1480.

(18 San Sebastiano Mantegna, 19 San Sebastiano detail)

(20 Hypnerotomachia fountain)

Come Polia et lui andorono allo littore aspectare Cupidine, ove era uno tempio destructo. Nel quale Polia suade a Poliphilo el vadi intro a mirare le cose antiche. Et quivi vide molti epitaphii, uno inferno depincto di musaico. Como per spavento de qui se partì et vene da Polia. Et quivi stanti vene Cupidine cum la navicula da sei Nymphe remigata. Nella quale ambo intrati, Amor fece vela cum le sue ale. Et quivi dagli Dii marini et Dee, et Nymphe et monstri li fu facto honore a Cupidine, giunseron all’insula Cytherea, la quale Poliphilo distincto in boschetti, prati, horti, et fiumi, et fonti plenamente la descrive, et li presenti fu fatti a Cupidine et lo accepto dalle Nymphe, et come sopra uno carro triumphante andorono ad uno mirando theatro tuto descripto. In mezo del’insula. Nel mezo dil quale è il fonte venereo di sete columne pretiose, et tutto che ivi fu facto, et venendo Marte d’indi se partirono et andorono al fonte, ove era la sepultura di Adone.

I imagine that this work served as a leading example for all the “artificial ruins” up to the 20th century, with its notion of a fleeting past to be renewed, where decay is not regarded as a catastrophe, but as an appealing example of the impermanence of things. I believe that such re-enactments of Antiquity, like La Villa d’Este and Bomarzo, Frederick the Great’s Sanssouci, Pfaueninsel, Ermenonville and le Désert de Retz (to mention only a few renowned European gardens), and perhaps even Albert Speer’s concept of a “ruin value” derive directly from Poliphilo’s dream on Aphrodite’s island.

(21 Hypnerotomachia ruin)

What I would like to say in conclusion is that the künstlische Ruine is always Romantic, but at the same time it bears witness to a progressive concept of History, which is typically “Enlightenment”. And the origin of this idea of the ruin as a constant renewal comes from the Renaissance period and, more specifically, from the Renaissance vision of the classical age.

Perhaps, you are waiting to see my own interpretation of the voyage to Cythera. Like all the artists and authors previously mentioned, I have never been to the island. If I were to create works devoted this theme, I would probably superimpose prints from The Strife of Love in a Dream on satellite images of this real island or, rather, to images of any archaeological site close to my house.

But why am I eventually interested in Cythera? Because it is a sort of paradigm of the gap between a real place and the images of it created and transmitted by past cultures. And this is a fertile gap.

.

SP, April 2018, reviewed February 2019

(Thanks to Riccardo Lo Giudice for his revision and advice)

.

Notes :

(1) http://www.tk – 21.com/Gulliver -a- Lavera.

(2) Journal of the Warburg Institute, vol. I, n. 1, July 1937.

(3) I owe, among other findings, the discovery of this cycle to Gilles Tiberghien’s Art, nature paysage, Arles 2001.

(4) Forests. The Shadows of Civilization, Stanford 1992.

(5) Purgatorio, XXVIII, 142-143.

(6) Introduction to Boschi d’Italia, Roma 1993.

(7) Aki Taguchi, Nerval. Recherche de l’autre et conquête de soi, Bern 2010. Another possible source for Nerval’s vision of contemporary Cythera: F. Poqueville, Travels in the Morea, London 1813.

(8) I would like to recommend an excellent site for the southern European iconographical research: http://travelogues.gr, published by the Aikaterini Laskaridis Foundation.

(9) Among the recent articles on the Hypnerotomachia I recommend “Hypnerotomachia Poliphili – an object of Material Culture”, published in Bern, Switzerland, in October 2014 (http://www.2xd.ch/2014/10/hypnerotomachia-poliphili-an-object-of-material-culture/). See also Esteban Alejandro Cruz digital reconstructions of Poliphilo’s gardens and monuments: Hypnerotomachia Poliphili: An Architectural Vision from the First Renaissance, 2011, in two volumes, and Word & Image A Journal of Verbal/Visual Enquiry, Volume 31, 2015 – Issue 2: Hypnerotomachia Poliphili Revisited.

A facsimile of the book, by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology: http://mitpress2.mit.edu/e-books/HP/hyp000.htm.

.

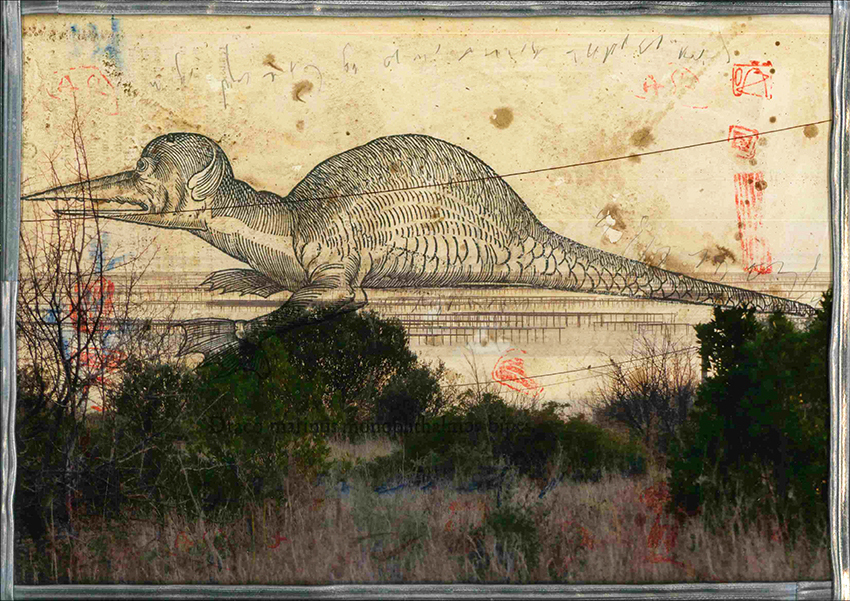

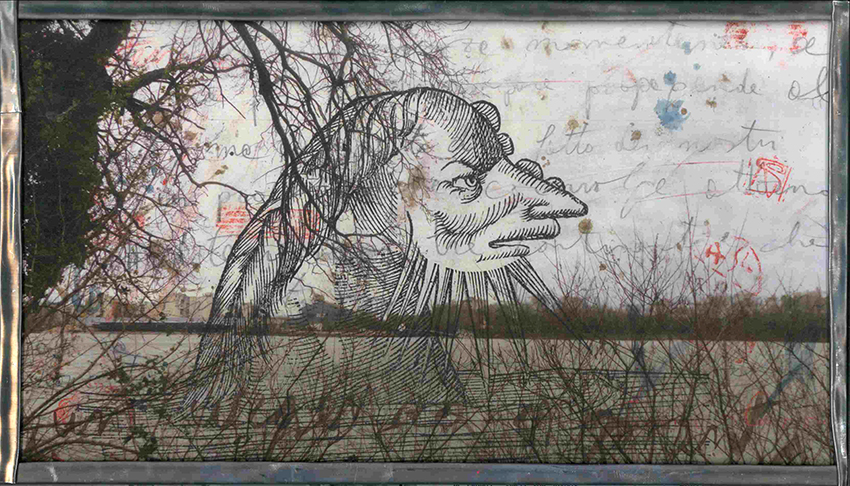

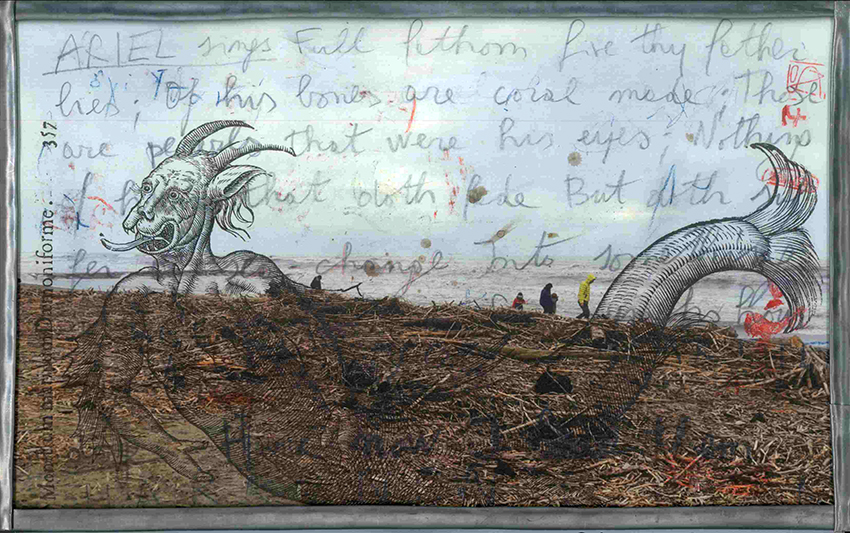

Histoire des monstres 02, Don’Ana-Andura Piscis, 2021, 24×42.

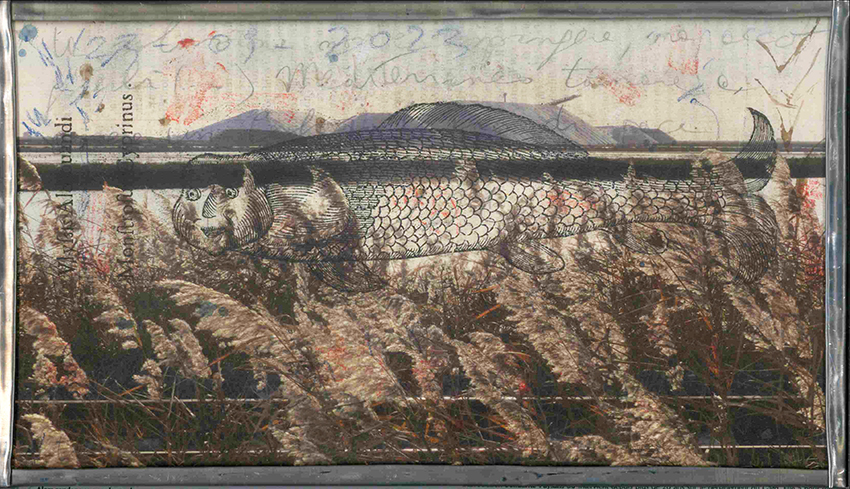

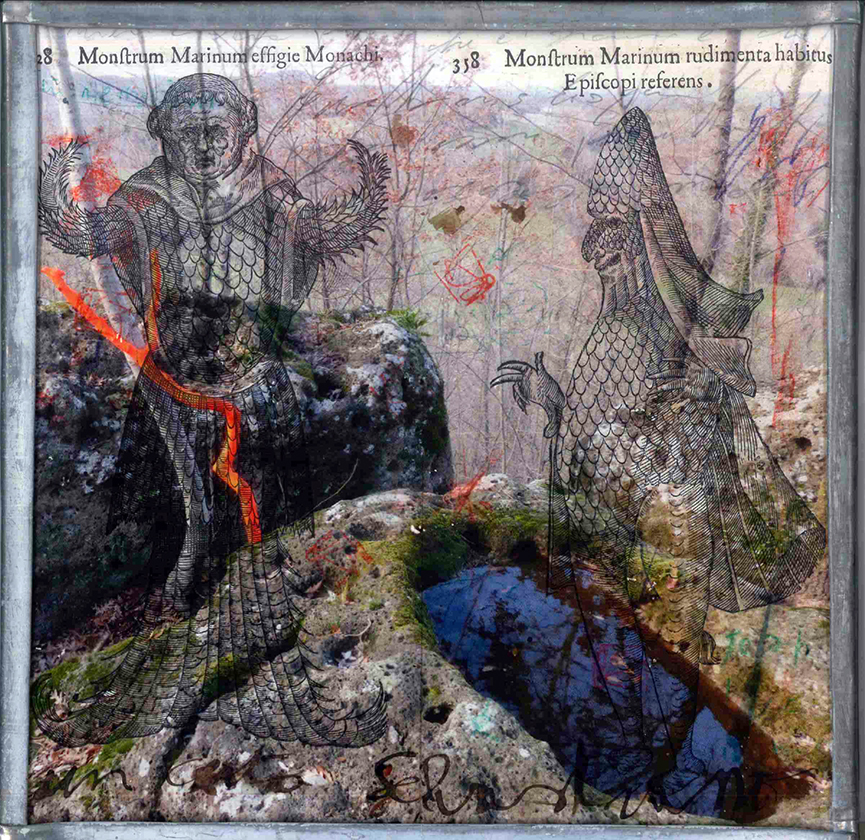

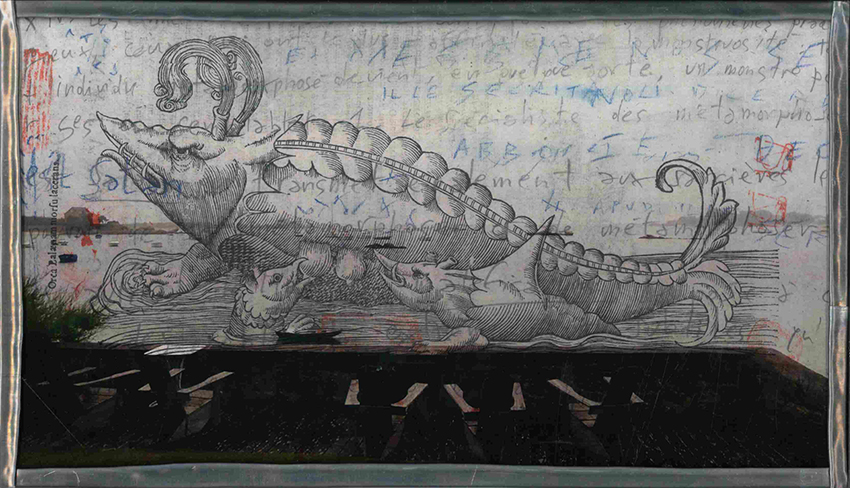

Histoire des monstres 02, Don’Ana-Andura Piscis, 2021, 24×42. Nuovi mostri 04, Sète-Elephas Marinus, 2023, 30×40.

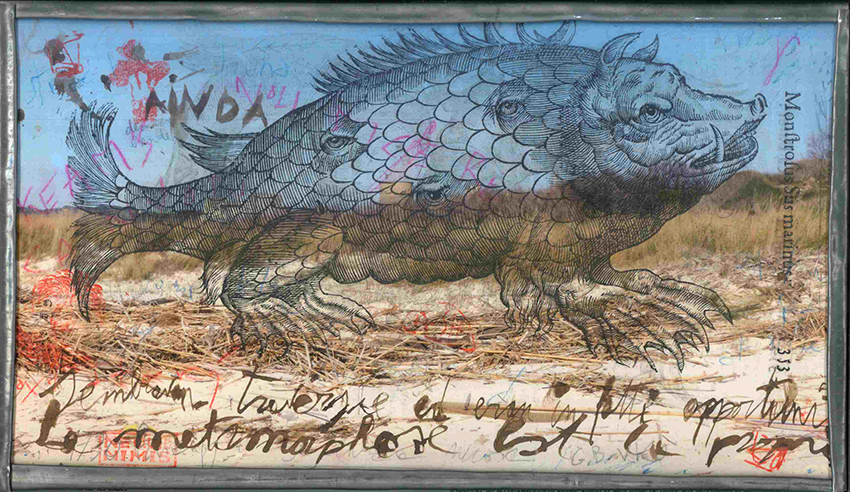

Nuovi mostri 04, Sète-Elephas Marinus, 2023, 30×40. Nuovi mostri 05, Mèze-Draco marinus, 2023, 30×40.

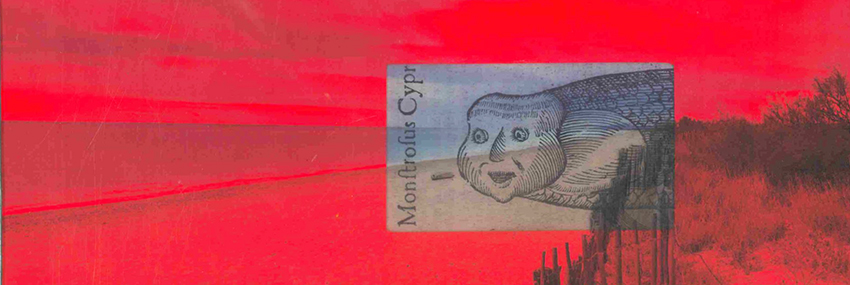

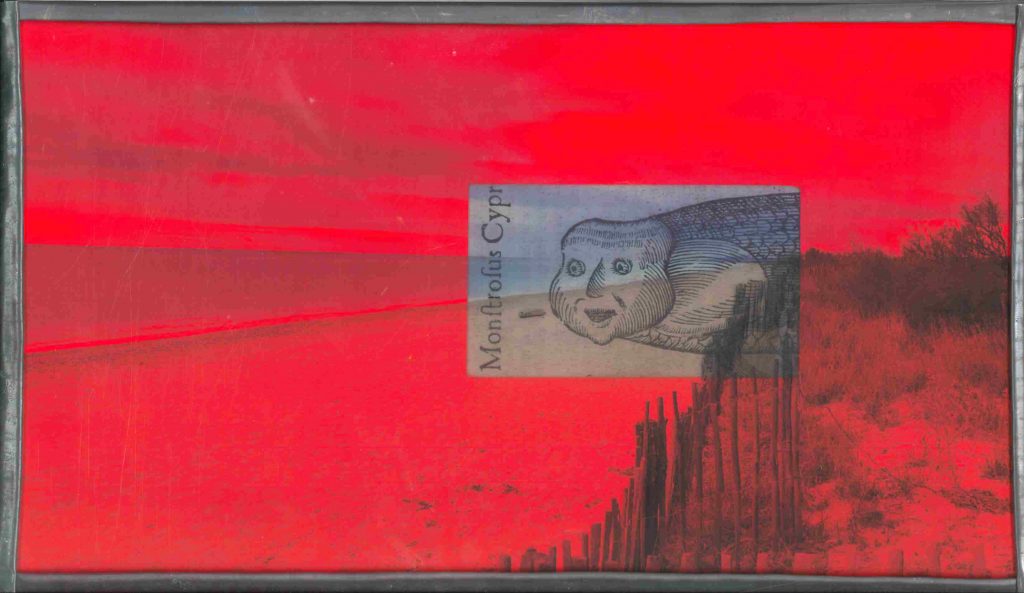

Nuovi mostri 05, Mèze-Draco marinus, 2023, 30×40. HdM 16 bis, Maguelone-Monstrosus Cyprinus, 2023, 24×42.

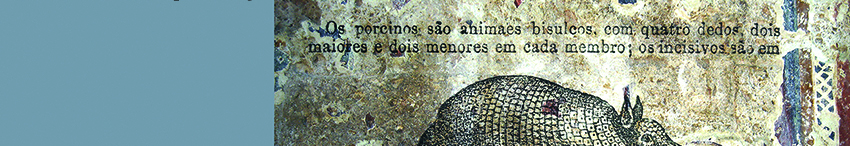

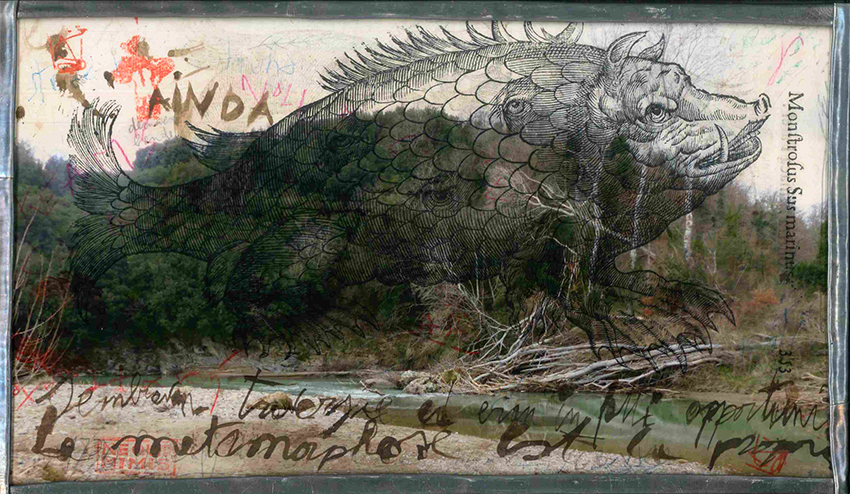

HdM 16 bis, Maguelone-Monstrosus Cyprinus, 2023, 24×42. Histoire des monstres 20, Rosignano Solvay-Sus marinus, 24×42, 2024.

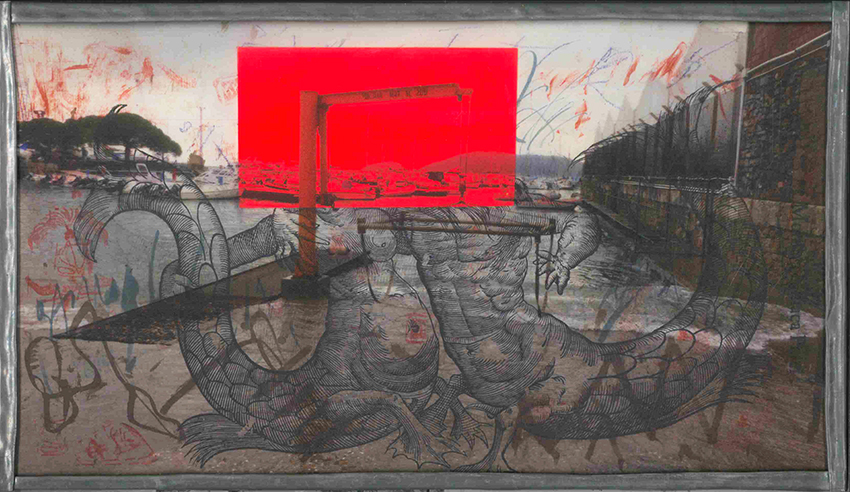

Histoire des monstres 20, Rosignano Solvay-Sus marinus, 24×42, 2024. Histoire des monstres 21, La Spezia Fincantieri-Niliaca parei, 2024, 24×42.

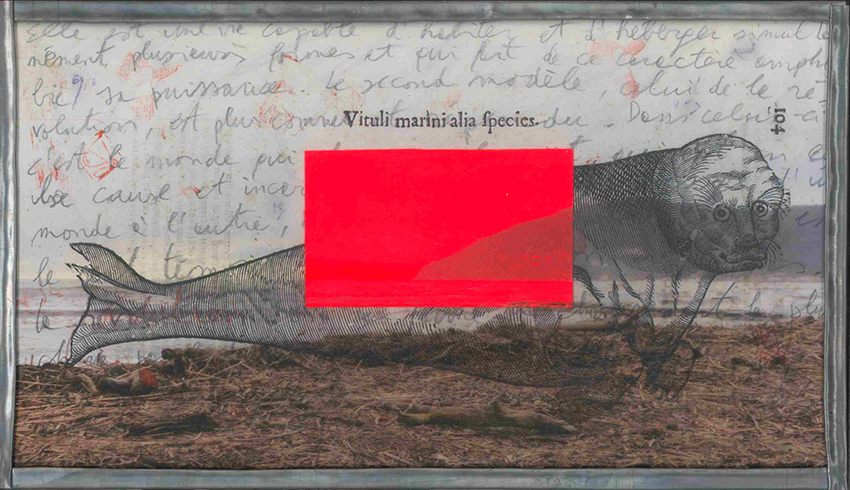

Histoire des monstres 21, La Spezia Fincantieri-Niliaca parei, 2024, 24×42. Histoire des monstres 22, Marinella di Sarzana-Vituli marini, 2024, 24×42.

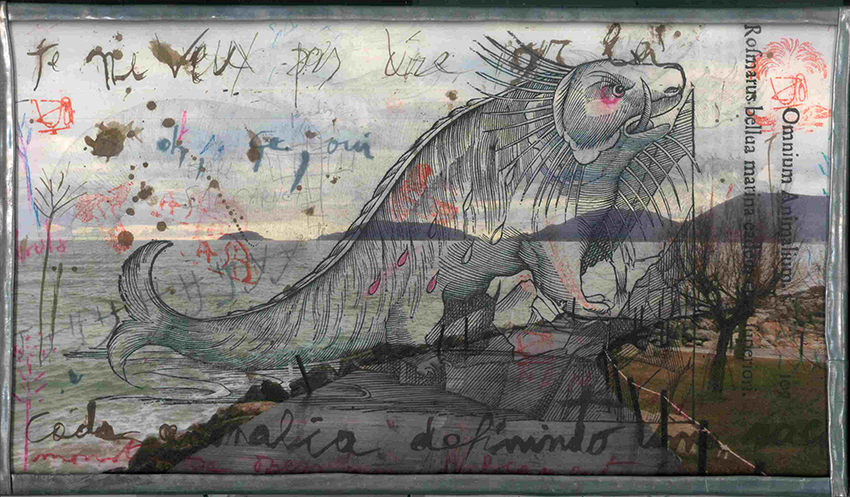

Histoire des monstres 22, Marinella di Sarzana-Vituli marini, 2024, 24×42. Histoire des monstres 23, San Terenzio-Rosmarus bellua, 2024, 24×42.

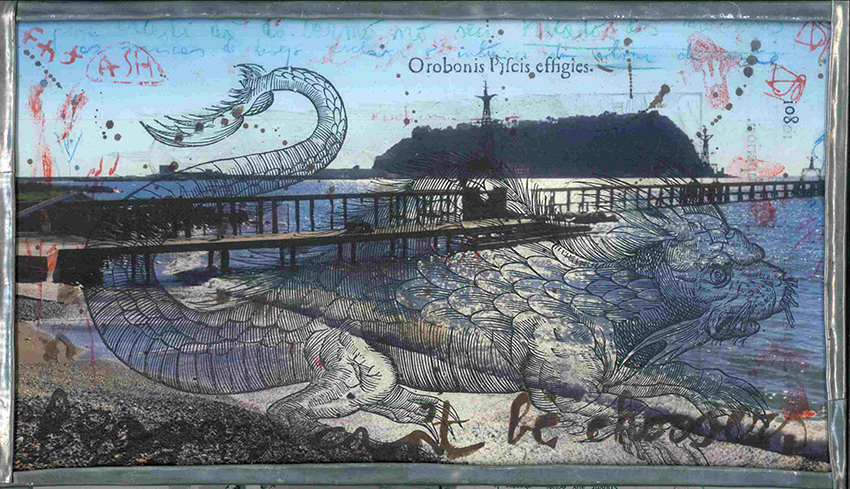

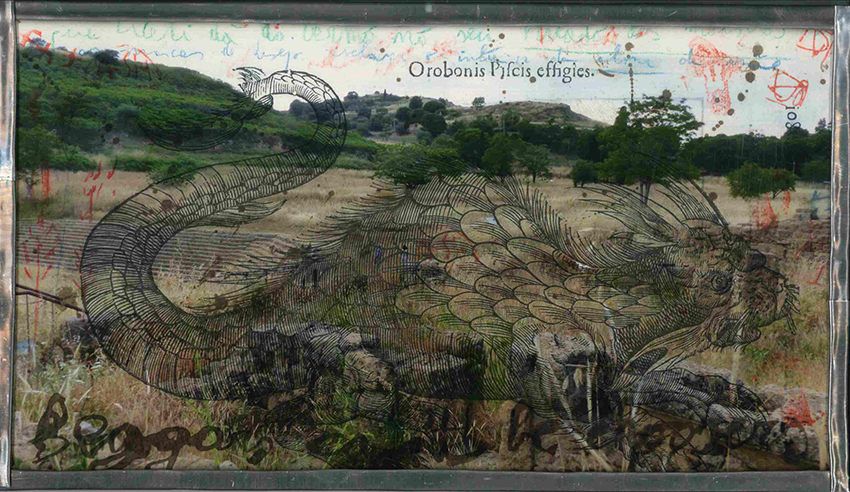

Histoire des monstres 23, San Terenzio-Rosmarus bellua, 2024, 24×42. Histoire des monstres 24, Nisida-Orobonis Piscis, 2024, 24×42.

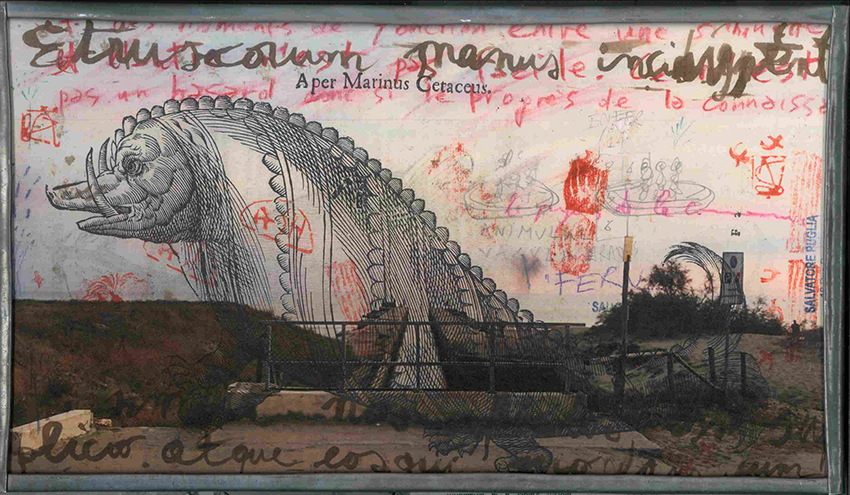

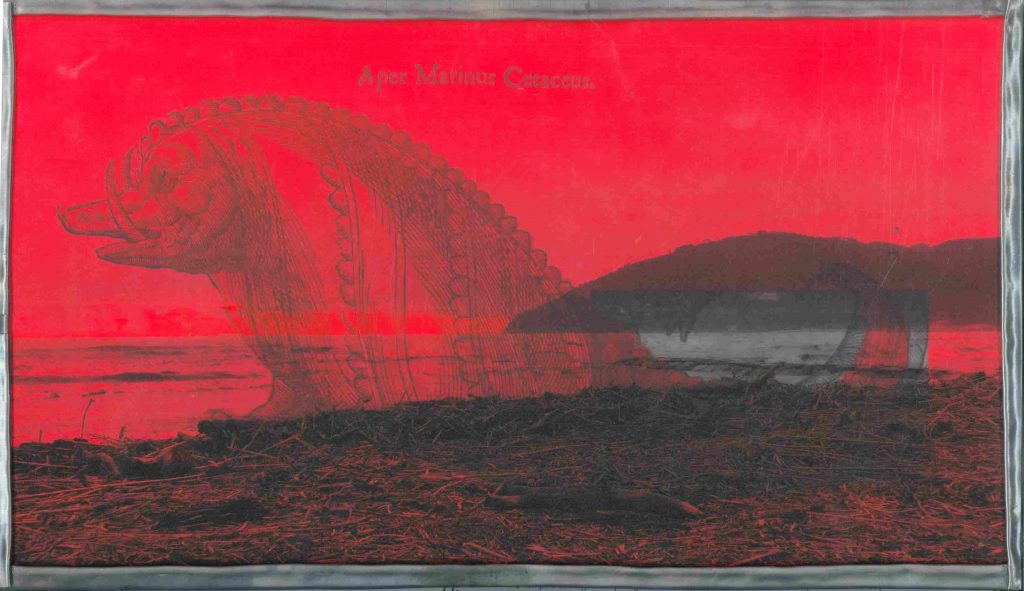

Histoire des monstres 24, Nisida-Orobonis Piscis, 2024, 24×42. Histoire des monstres 25, La Bufalara-Aper Marinus, 2024, 24×42.

Histoire des monstres 25, La Bufalara-Aper Marinus, 2024, 24×42. Histoire des monstres 27, Finistère-Orca Balaenam, 2024, 24×42.

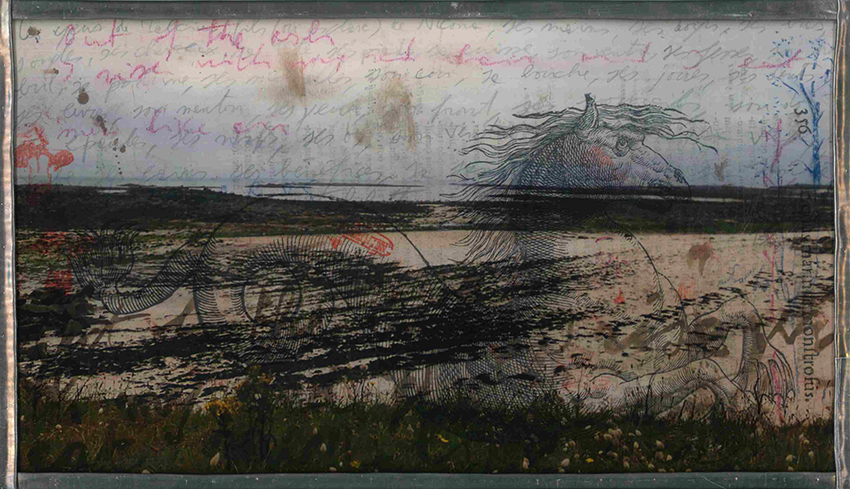

Histoire des monstres 27, Finistère-Orca Balaenam, 2024, 24×42. Histoire des monstres 31, Arles-Cetus capillatus, 2024,24×42.

Histoire des monstres 31, Arles-Cetus capillatus, 2024,24×42. Histoire des monstres 32, Aigues Mortes-Monstrosus Cyprinus, 2024, 24×42.

Histoire des monstres 32, Aigues Mortes-Monstrosus Cyprinus, 2024, 24×42. HdM 22 bis, Marinella di Sarzana-Aper Marinus, 2024, 24×42.

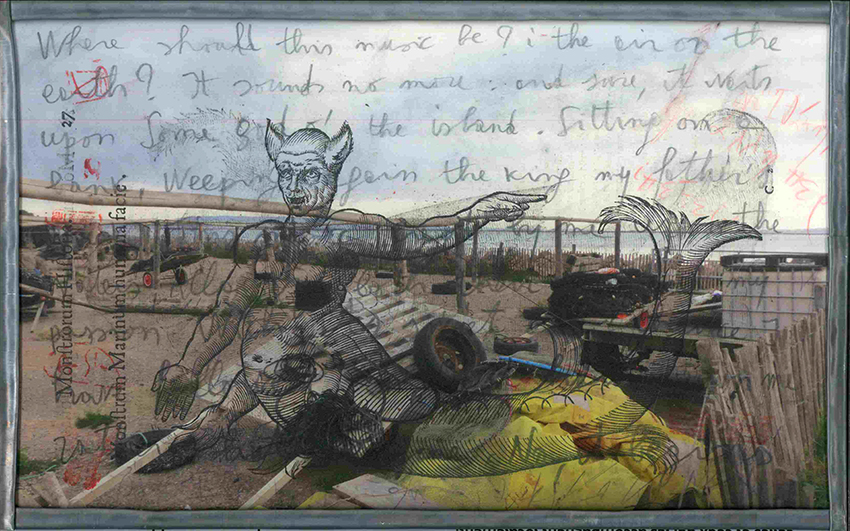

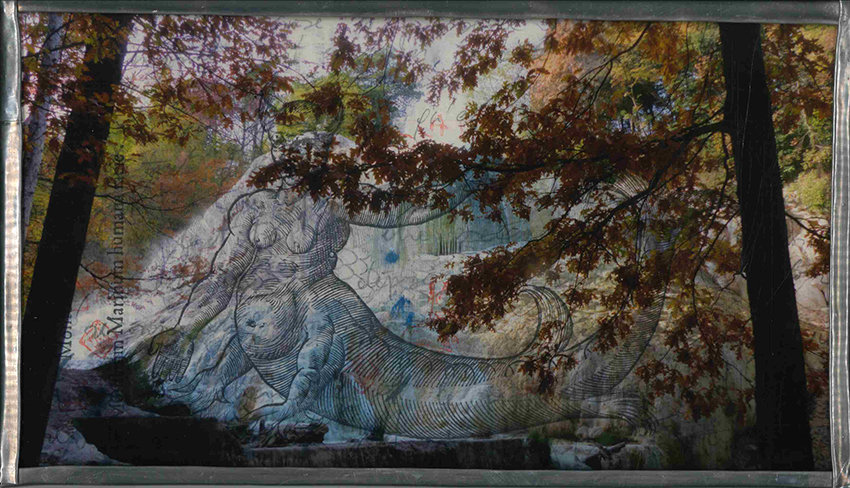

HdM 22 bis, Marinella di Sarzana-Aper Marinus, 2024, 24×42. Histoire des monstres 33, Mèze-humana facie, 2024, 26×42.

Histoire des monstres 33, Mèze-humana facie, 2024, 26×42. Histoire des monstres 34, Marinella di Sarzana-Daemoniforme,2024, 26×42.

Histoire des monstres 34, Marinella di Sarzana-Daemoniforme,2024, 26×42. Histoire des monstres 35, Vado Ligure-Andura piscis, 2024, 24×42.

Histoire des monstres 35, Vado Ligure-Andura piscis, 2024, 24×42.

Histoire des monstres 00, Poggio Rota, 30×30, completed December 13.

Histoire des monstres 00, Poggio Rota, 30×30, completed December 13. Histoire des monstres 01, Fiora, 24×42, completed December 15.

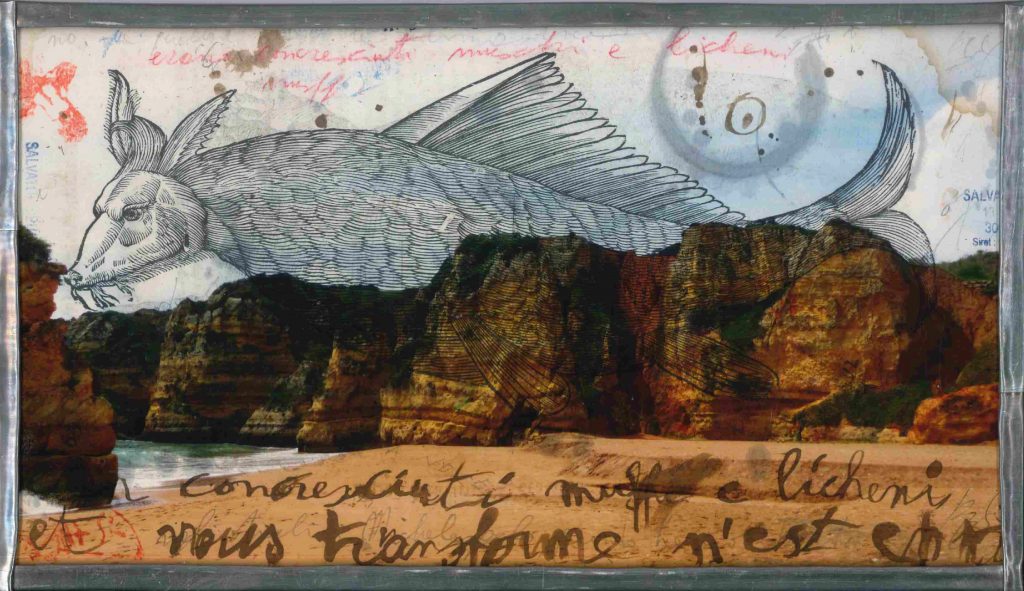

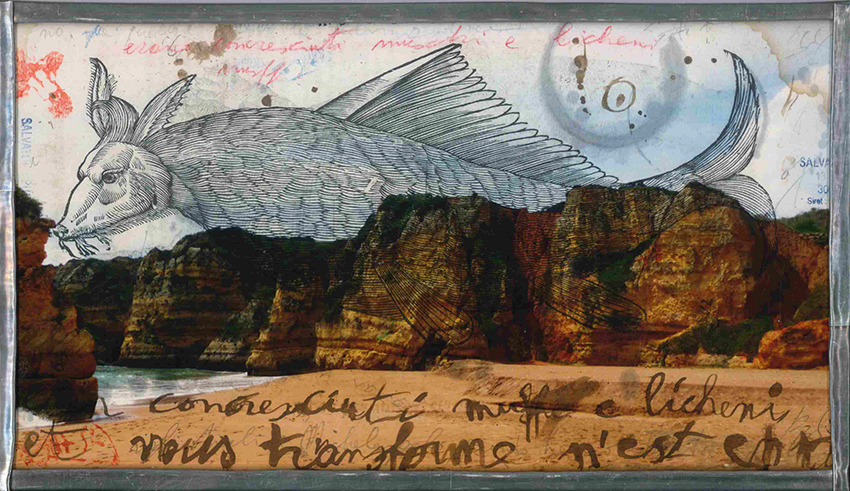

Histoire des monstres 01, Fiora, 24×42, completed December 15. Histoire des monstres 02, Lagos, 24×42, completed December 16.

Histoire des monstres 02, Lagos, 24×42, completed December 16. Histoire des monstres 03, Rofalco, 24×42, completed December 17.

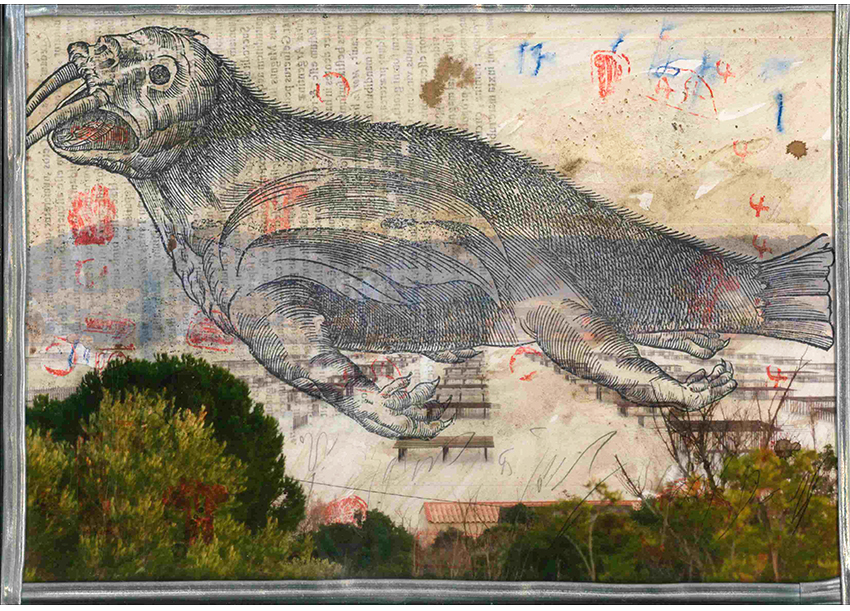

Histoire des monstres 03, Rofalco, 24×42, completed December 17. Histoire des monstres 04, Morgantina, 24×42, completed Decembre 19.

Histoire des monstres 04, Morgantina, 24×42, completed Decembre 19. Histoire des monstres 05, Castro, 24×42, completed December 20.

Histoire des monstres 05, Castro, 24×42, completed December 20. Histoire des monstres 06, Brignogan-Plage, 24×42, completed December 22.

Histoire des monstres 06, Brignogan-Plage, 24×42, completed December 22. Histoire des monstres 07, Fratenuti, 24×42, completed December 24.

Histoire des monstres 07, Fratenuti, 24×42, completed December 24. Histoire des monstres 08, Batz, 24×42, completed December 25.

Histoire des monstres 08, Batz, 24×42, completed December 25. Histoire des monstres 09, Fosso bianco, 24×42, completed December 26.

Histoire des monstres 09, Fosso bianco, 24×42, completed December 26. Histoire des monstres 10, Balena bianca, 24×42, completed December 27.

Histoire des monstres 10, Balena bianca, 24×42, completed December 27. Histoire des monstres 11, Camp de César, 24×42, completed December 28.

Histoire des monstres 11, Camp de César, 24×42, completed December 28. Histoire des monstres 12, Ponte san Pietro, 24×42, completed December 29.

Histoire des monstres 12, Ponte san Pietro, 24×42, completed December 29. .

.

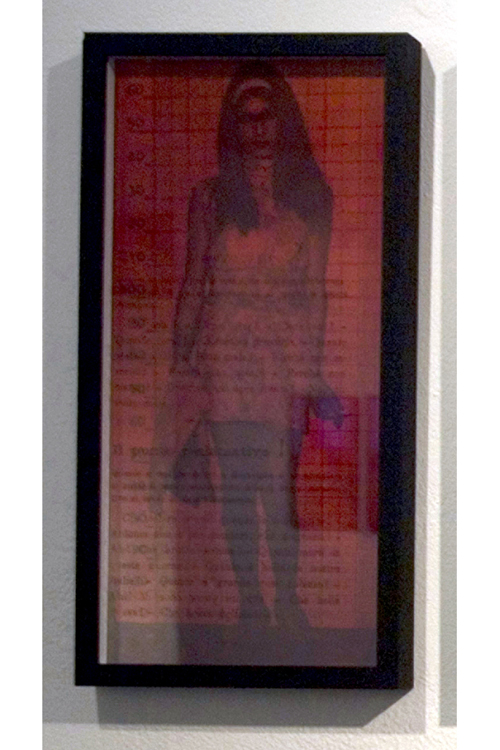

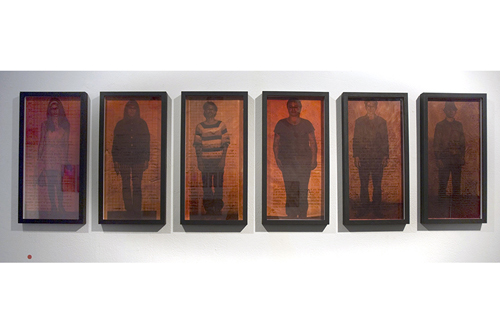

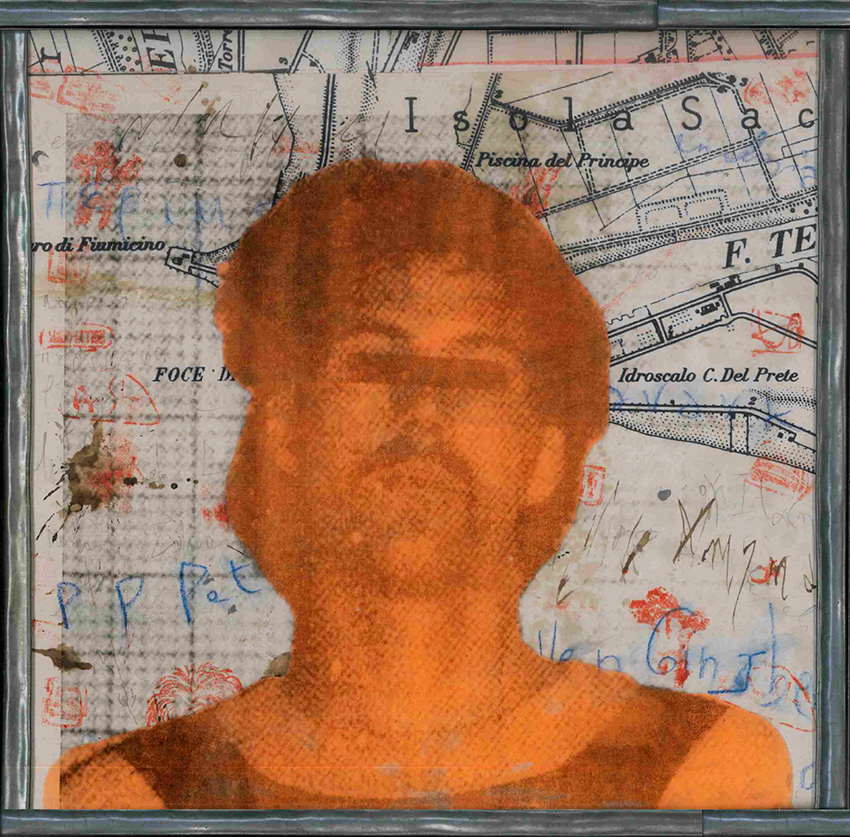

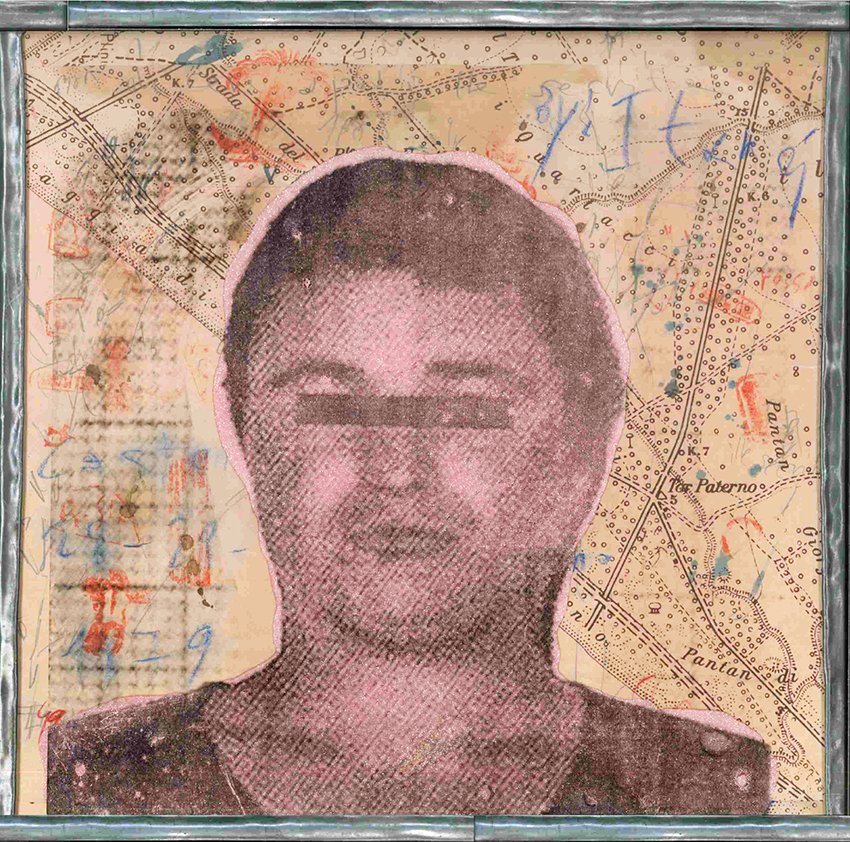

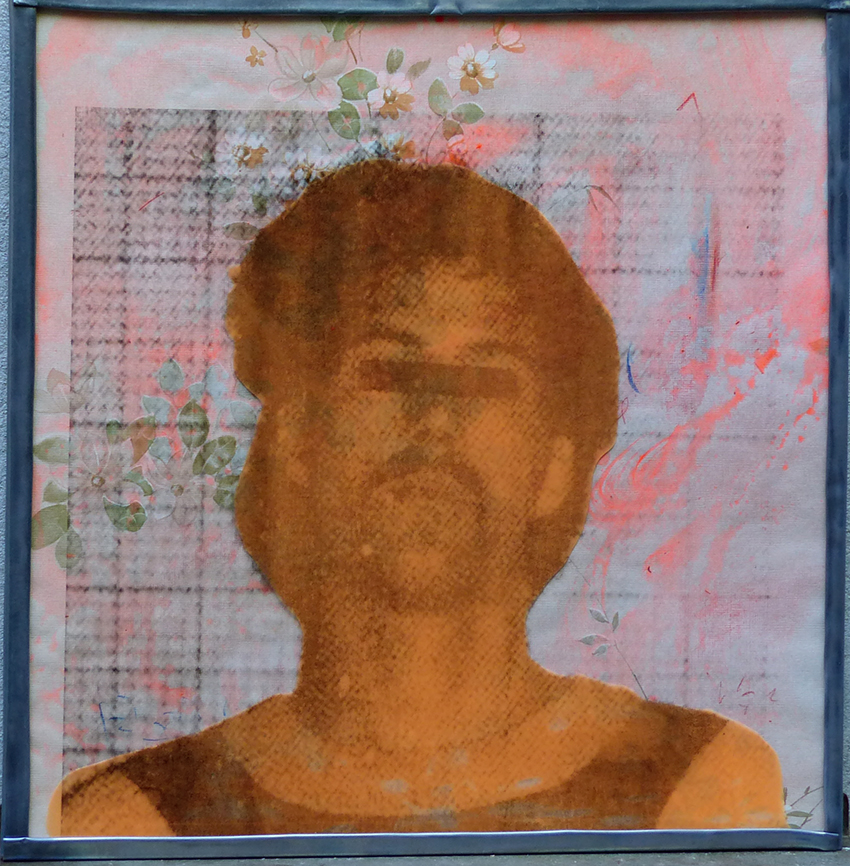

Anni Settanta 01, Idroscalo, 32×32, 2023.

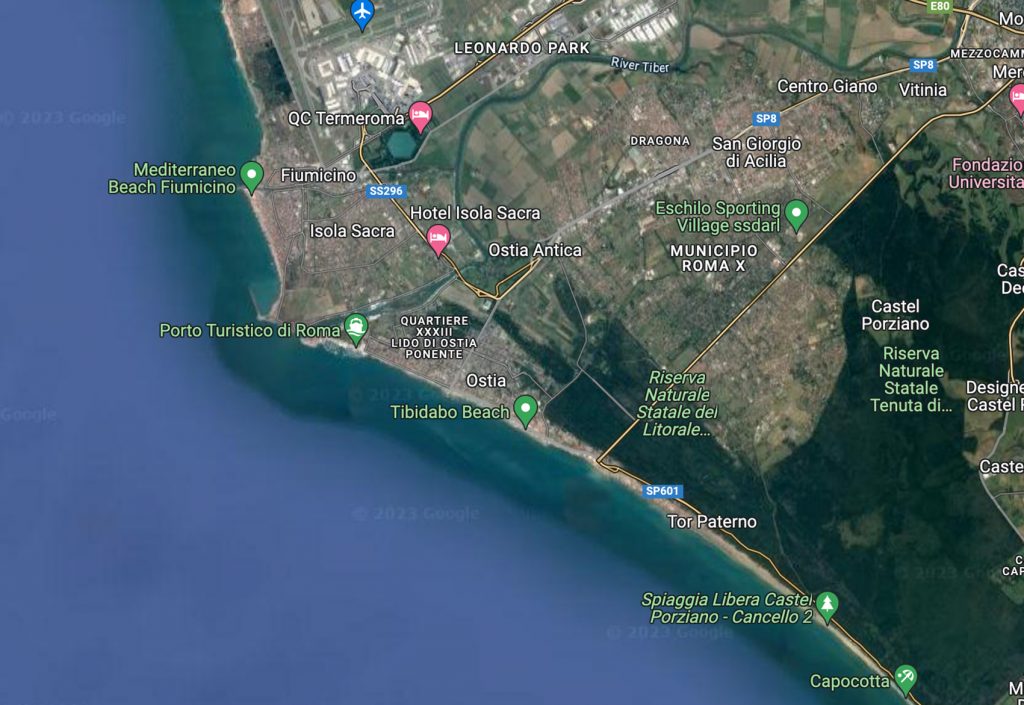

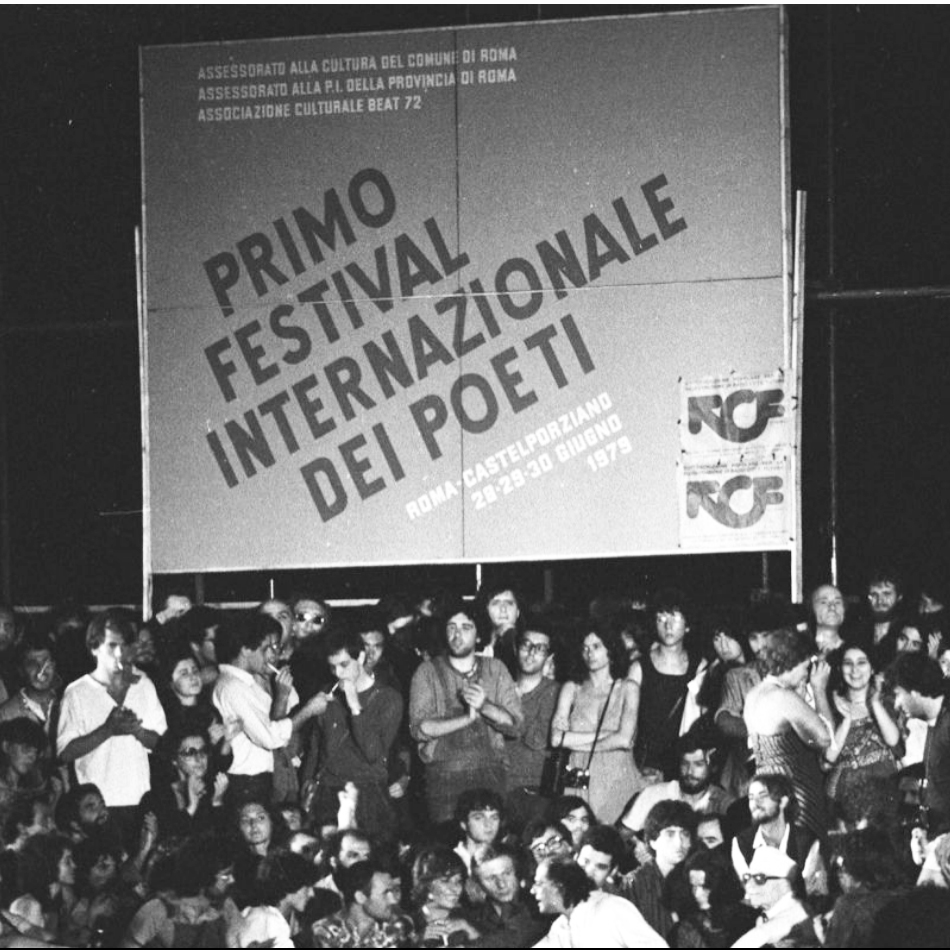

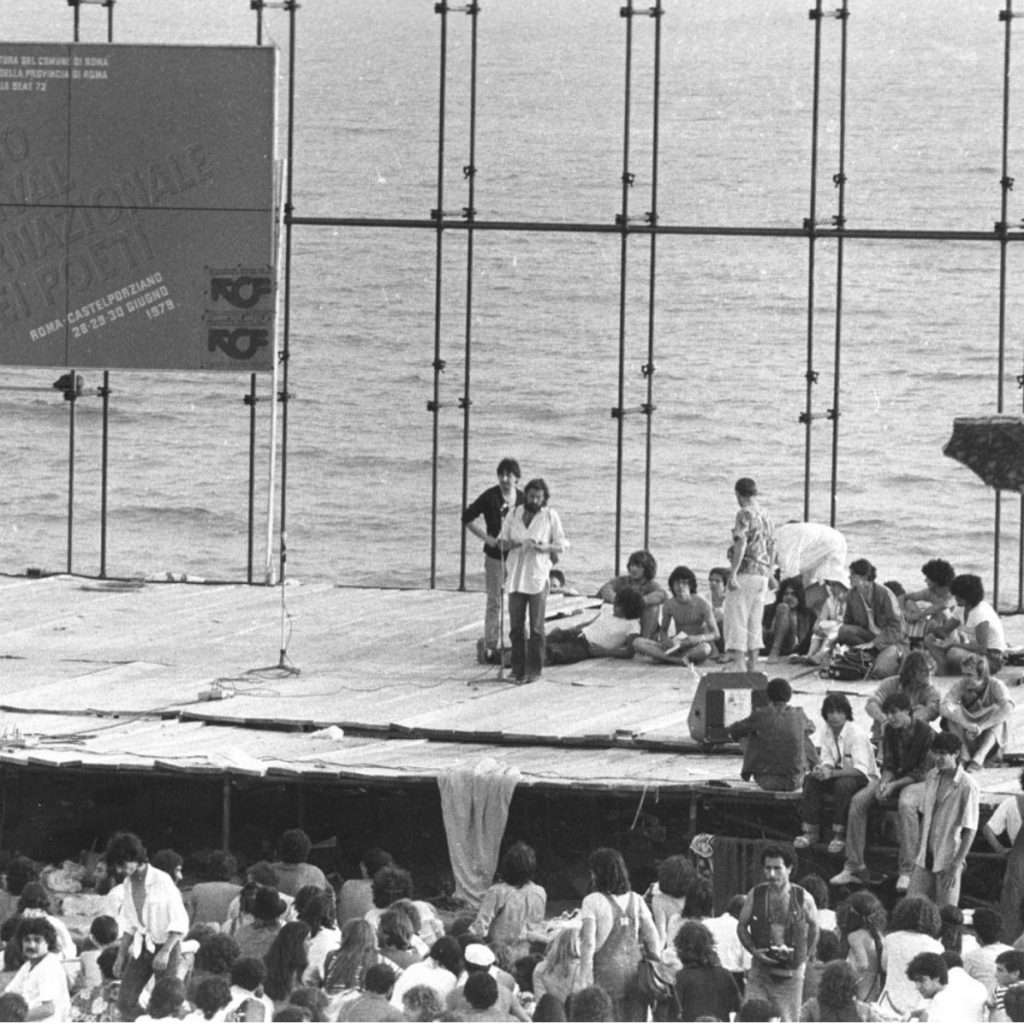

Anni Settanta 01, Idroscalo, 32×32, 2023. Anni Settanta 02, Castelporziano, 32×32, 2023.

Anni Settanta 02, Castelporziano, 32×32, 2023. Anni Settanta 03, Capocotta, 32×32, 2023.

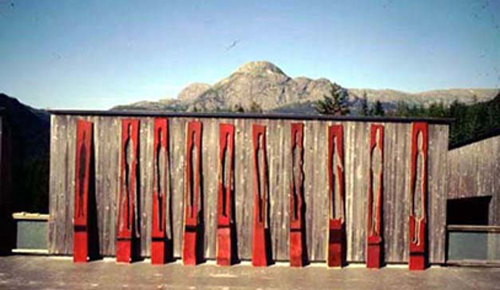

Anni Settanta 03, Capocotta, 32×32, 2023. Wallflowers remix 02, 32×32, 2010.

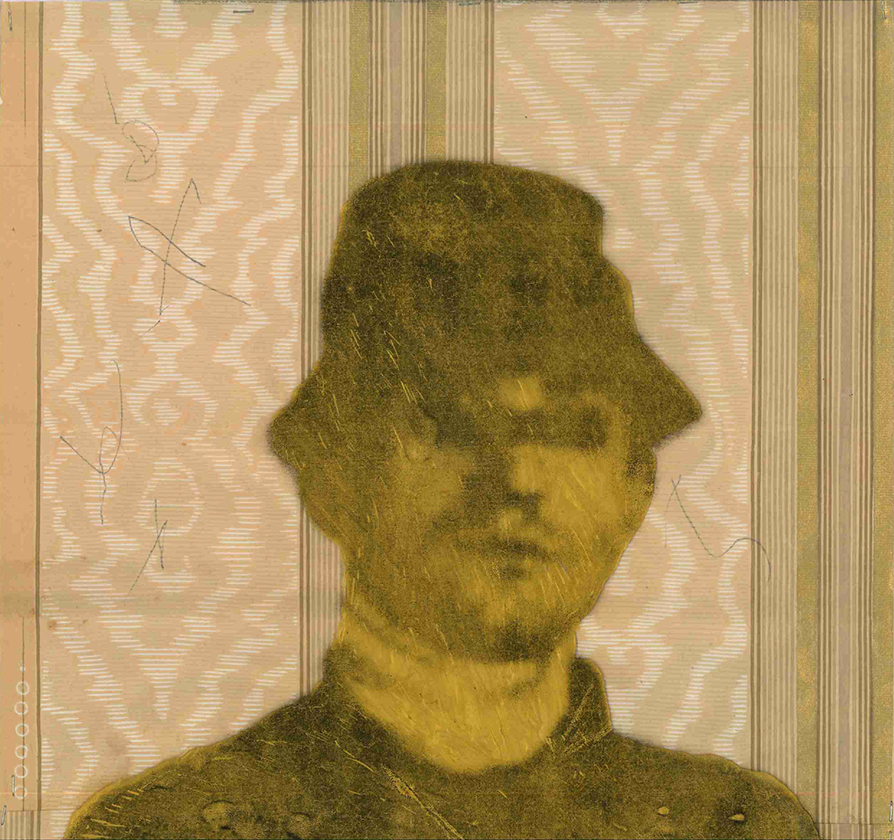

Wallflowers remix 02, 32×32, 2010. Wallflowers remix 04, 32×32, 2010.

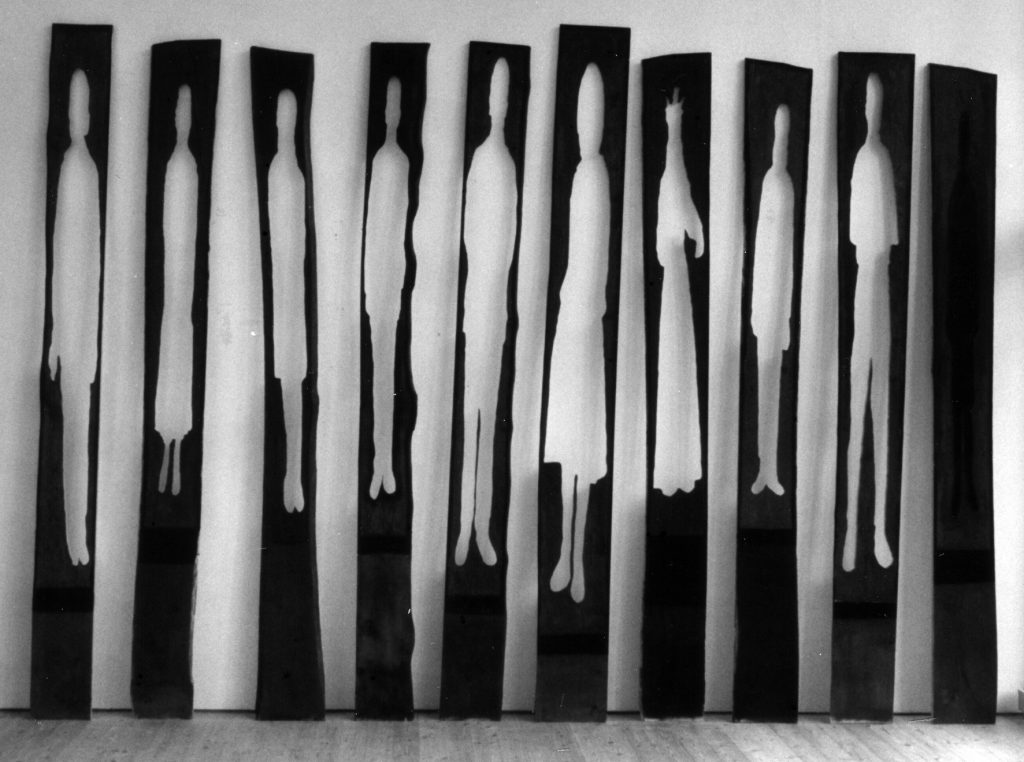

Wallflowers remix 04, 32×32, 2010. Wallflowers remix 06, 32×32, 2010.

Wallflowers remix 06, 32×32, 2010.

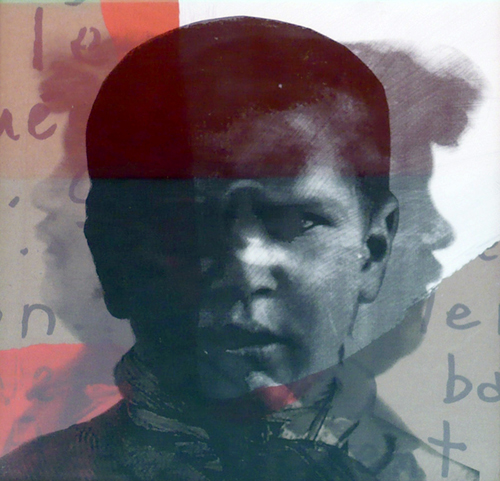

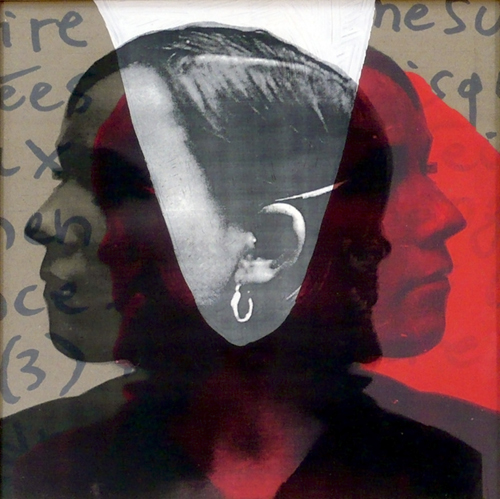

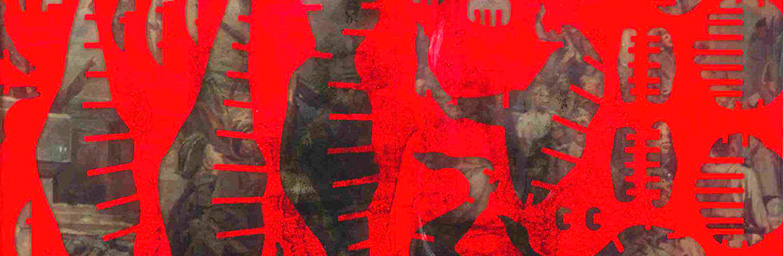

Anabasis 09 B, 40×60, 2018.

Anabasis 09 B, 40×60, 2018.

Anabasis 05 B, 40×60, 2021 (2015).

Anabasis 05 B, 40×60, 2021 (2015).