I’ll start with the usual question

“How should you introduce yourself to the Serbian public? You are Salvatore Puglia, an Italian artist…or maybe a European artist or just an artist?”

Italian and European, I would say. I cannot conceive of art or an artist detached from any historical context, and the context of my artistic (and associated political) formation and commitment was Italy and, more generally, Europe in the 1970s.

As far as I can remember, my interest in art developed by reading the popular art history series entitled I Maestri del colore (published weekly by Fratelli Fabbri Editori from 1963 to 1967), which my father, a simple public clerk, bought every Sunday at the newspaper stand around the corner for the equivalent of 15 centimes of euros. The texts were written by most renowned international art historians. I was also inspired by all the encyclopaedias, sold door to door, that my father put on the shelves and never touched.

These were the ‘optimistic’ years, when families had extra money, housing was affordable and culture was relatively accessible.

“High” and “low” cultures have never been as close as in those years.

I also recall watching L’Odissea, the 1968 Italian-German-French-Yugoslavian primetime TV production starring Bekim Fehmiou, which was introduced by the greatest Italian poet, Giuseppe Ungaretti.

A few words about your political and artistic formation in that period. Were you politically active? Who were your artistic heroes back in those days? (L’Odissea was quite popular at the time, have you heard that great Yugoslavian actor Fehmiu wrote an excellent biographical book before he committed suicide in 2010?)

I didn’t know who Fehmiou was, before purchasing the Odyssey on DVD a few years ago to show to my children.

In 1967 (at the age of fourteen), I recall saying to my friends, out of school, that we need “order” (my father was an ex-paratrooper in the Salò Republic, and my mother a Mussolini fan, like Sophia Loren in Ettore Scola’s film Una giornata particolare).

In 1968, I took part in a street demonstration after Yan Palach’s suicide and against the Soviet Union invasion of Czechoslovakia. I remember having been a bit bothered by the far right students dressed in black, who were clearly manipulating the event.

As a young Catholic, I was active in my local parish, played soccer, and began mobilizing to combat leprosy in Africa. I remember making a big poster — not very different from the kind of images I create today with archive photographs — depicting a girl afflicted with leprosy, partially covered by red translucent paint, and underneath the caption: “She doesn’t use Kaloderma”.

Around the age of 16, I became influenced by the South American theology of liberation, and I linked it to the Guevarist myth. Within a few months, I became acquainted with leftist ideas at my high school.

However, at that time I had closer contacts with my right-wing colleagues, and one day, I returned home with a broken nose, and told my mother that it happened by running into a volleyball pole (and not from a karate chop). But, still, we were mostly using clenched fists and sometimes sticks against each other, not weapons.

I entered university with the intention of studying art history, with a specialisation in Etruscology, but as I was very involved in the student movement, and soon found such studies too aristocratic and not masculine enough. I never studied much, but eventually, I managed to graduate with a degree in social history.

In 1973, after the coup in Chile and following rumours of an attempted military uprising in Italy, I volunteered to undertake my military service, with the idea of convincing my comrades to offset the rumoured coup, which never took place. I was fortunate that my clandestine activities were never discovered.

Back from my fourteen months as a simple soldier, I was eager to start working immediately and found employment as a teacher in a primary school for one year. I soon realised that pedagogy was not my favourite field. I was too emotional for being an arbiter of knowledge for children. And, once again, I was too involved in political battles. By March 1977, it became impossible to go out in the streets without being squeezed between the opposite violence of the State and the more aggressive leftists, the “Autonomi”. I went back, with a few friends, to more humble everyday political activities in my area, trying to convince retired or marginal neighbours to reduce their telephone and electricity bills, and also organising a kind of direct meat market, against the monopolistic distribution of the traditional food supply chain. I did not meet with much success in those endeavours.

I subsequently worked in the historical field, in revues and with grants for practising archival research. Three months after securing a permanent position, I decided to quit and signed a resignation letter, leaving first to Barcelona, then to Paris. It was late 1985.

My artistic heroes? After an initial period in Paris, in 1979-1980: Twombly, Tàpies, Bram Van Velde. In June 1977 when in Bologna to complete my history studies, I saw performances by Hermann Nitsch and Marina Abramovic. The word itself “performance” came as a revelation to me.

Why is the word “performance” so special to you? Fehmiu, Abramovic… The name of two Yugoslavian artists appeared in this conversation in a short period of time. How did the violent break-up of Yugoslavia affect you as a European (Yugoslavia was a sort of precursor of todays unified EU) and a neighbour?

“Performance”: simply the idea that the beauty of a gesture could be comparable, and no less impressive, than the beauty of a painting. To release two rabbits in a gallery space, or to sit at a piano without knowing how to play piano, and still transmit an emotion. Or to invite passers by to brush your naked body, like Abramovic and Ulay did in Bologna. And the fact that what matters is that it “existed”, independently of the presence of the public.

To me, in those years, Yugoslavia was an Eastern European place where you could go relatively easily, as I did with my motorbike, when I was sixteen. During one summer I drove from Zadar to Dubrovnik to Mostar and Sarajevo (I haven’t been to Serbia) talking with anybody that could communicate in English or Italian, but I never felt that there was an “ethnic problem”. It is true that I was more interested in getting a hammer for pitching my tent, in seaside camping sites popular with British or Hungarian girls. In that sense, we were fully in Europe. And the breakup of Yugoslavia, in the early 1970s was yet to come.

Can you say more about your artistic beginnings? Your first exhibition?

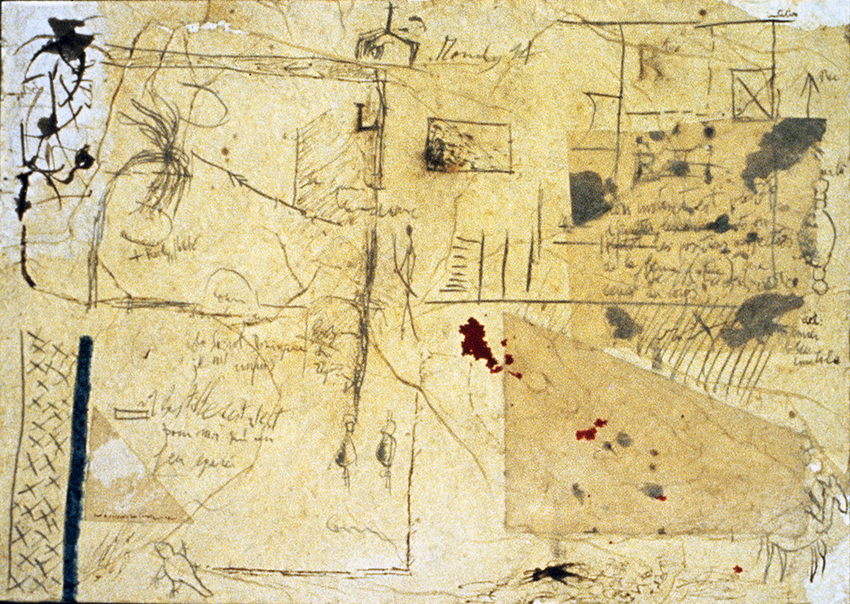

One of the six roommates with whom I shared a large apartment in Rome brought home a young French man he had met while hitchhiking in Sardinia. This Frenchman was studying philosophy and went on to become a musician. We developed a friendship, and I eventually went to visit him in France. At that time I was undertaking research in the archives of Rome and the Vatican, and sometimes I would take home left-over papers or copies of documents that would be not be missed by other researchers. With these fragments of history, I made collages and small watercolours, and sent them to him, and other friends. He collected them in a folder and started visiting art galleries (as he told me only subsequently). Then one day he phoned, announcing that I was going to have a show at the ADEAS, the gallery affiliated with the Strasbourg School of Architecture. He had already fixed the dates, so there was no way to refuse. (01-02-03)

I took a night train bringing along other new and bigger works that were hastily made in the limited time available (maybe a month).

I arrived early in the morning in Strasbourg. He was waiting for me at the train station with another friend who spent the next few days framing my works and preparing the gallery space.

I remember that upon arrival, at six o`clock in the morning, they took me for breakfast to a coffee shop, which was already open: Café Italia. On the glass door there was a poster: my name and the title of the show, Falsapartenza, were written on it. This was in October 1985.

Great story! What appeared as a lost for the Vatican turned out to be of great benefit for the art! Have you, by chance, any photo of your work from that period? Visual artists usually started from the scratch, they are forced to stare at the blankness of the paper or the canvas, but you deal with the document from your early beginnings. Thus you’ve situated yourself firmly in History, right?

I think I never glanced at a wall or a canvas waiting for “inspiration”. I rather started with a piece, a fragment of something found somewhere. The challenge was how to create a new context for it, or to present an altered version of its original context. I graduated in history with a thesis on the revolutionary year, 1848, in a neighbourhood located in the centre of Rome. Thanks to the police and law court archives, I was able to examine everyday life in a relatively small community and its apparent harmony and underlying contradictions; and that revealed a sort of breach in time. Then, I noted that people split and took sides, but as a prolongation and amplification of existing relations.

Today, we are in a counterrevolutionary period, in which people dare and are emboldened to say what they might be ashamed to think (as an example, the rumours against foreigners and migrants and those who assist them).

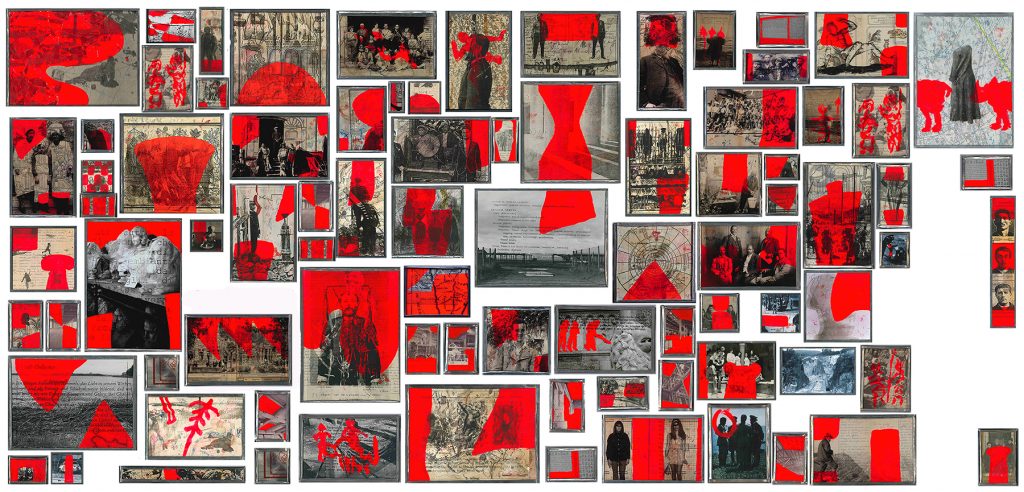

I am currently working at a large installation, which I will probably call Millenovecento, and which focuses on the last century. But my most recent piece is a tote bag that I sold as a limited edition on the Internet. It bears a quote from a letter of an Italian political prisoner, seized by the Fascist police in the 1920s. The language this anarchist or communist worker from the village of Manziana employs is not quite grammatically correct but expressive: Noi altri compagni semo tutti isolati, aspettiamo il momento che ci venga rischiarata un pò di luce che ora vivemo nelle tenebre (We comrades are all isolated, we are waiting for the moment that some light will come to us because we now live in darkness.). (04-05-06)

We are witnesses that the Far Right is on the rise across the globe (USA, Hungary, Poland, Brazil, etc.) In Italy, Matteo Salvini, a rising star of the European far right, is unashamed about his enthusiasm about rehabilitating Benito Mussolini’s fascist legacy. An antifascist quote on a tote bag, could that be seen as sarcastic epitaph for the 20th century?

It is true that all the metaphors for the sun of the future, or the luminous spring, or the inevitable re-birth were used in political songs inspired by the Communist parties (in any case, by the left wing) started to become obsolete from 1989 onwards. What made me transcribe the letter of this political prisoner was the Messianic image of the light to come, but also this incipit: Noi altri compagni semo tutti isolati. By definition, a companion is with others, accompanies or is accompanied. And what struck me is the impossibility to say us. The old comrades from my politically-minded youth are still my fraternal friends, and they are still doing things, each one with his/her competences and possibilities, for a world where the idea of a with can survive. But still, like me, they paradoxically feel isolated amidst this wave “against the other” that is spreading around Europe (and other continents).

I dare say that we belong to an “enlightened” minority, fragmented and scattered, ideally linked by a few principles that come from our Catholic and Jacobin past: solidarity with the weaker, social justice, attraction to otherness.

Recently, I carried out an experiment. I had the tote bag quotation printed on a t-sheet and wore it around the Italian village were I live in summertime, and were most of the votes now go to the xenophobic parties (this village was a “red” one in the region until ten years ago): it is not that people were amused or surprised by my testimonial garment, they just didn’t care to read it. They were not interested in deciphering a text, which was just an image for them. (07)

Let’s get back to chronological order. After your first beginnings, in which directions did your art develop? Can we use the term “developing” as adequate in your specific case? Maybe “researching”, “finding new ways” is much better?

I think that the term “developing” can adequately refer to the initial stages of a creative journey, like a thread unraveling in unknown directions. But, again, the biographical element is essential. In those early years in Paris (where I moved when a girlfriend organized a show of my works in an apartment), the priority was to make a living, and then to “pay” for having fled my job, my fiancée, my friends and comrades in Italy. I found it normal that I would have to undergo a little suffering, and I accepted any kind of manual work in order to pay my rent and feed my loneliness. I also found time to go to free lectures at the Collège de France, but most of the intellectual figures I had known in my previous travels to Paris were no longer there (Barthes, Foucault). I often went to public libraries and I must say that my work, at that time, was an attempt to “translate” into visual the texts I was reading then (Hölderlin, Büchner, Derrida). Around 1989, thanks to a mutual friend Jacques Derrida became familiar with my work and wrote an essay on it, “Sauver les phénomènes”, which was published a few years later in a special issue of the revue Contretemps, with absolutely no comments or reactions from the world of contemporary art. (08-09-10-11-12)

In Paris, you broke all ties with your previous life. How long did you stay in France, and did you ever have any regrets?

The fact is that I cannot live in my native country without being politically and socially involved, and living abroad allowed me to devote myself exclusively to my work and to subsist on it. I was doomed to live from my work.

Moreover, I could no imagine going back to Italy saying, “I was wrong, actually I am not an historian, I am an artist”. And I was grateful to France for having given me the earliest feedback to my artistic activity; even if it originated from a group of friends, my first artistic endeavours in France nonetheless meant a recognition of my choice.

For almost twenty years, I used Paris as my home base: I had five or six different studios around the city; I undertook residencies in Nordic countries and the Netherlands; I had a studio in Brussels for several months, and beginning in 1990 I spent long time periods in Berlin, a city to which I was drawn owing to the presence of several good friends but also to the passion for “our” history that is instilled in me.

When my daughter was born in 2006, I moved to the South of France. Since then, my work has become less a research activity per se but rather a re-utilization of the documents I compiled over the years. Therefore in a certain sense, one could say that I am working on my own archives and my own history.

If we try to find distinguished markers of your art, which one should it be? In other words, can you help me map your art’s DNA? (From the top of my head, the most obvious markers would been history, ruins, memory, shadow…)

I recognize traces of my works in each of those markers, and I could maybe synthetize them with the word “melancholy”. I have always been influenced by short excerpts or quotations that I encountered while reading books. A short novel by the Romantic age Adelbert von Chamisso has guided me for many years: the story of Peter Schlemihl, who sells his shadow to the devil in exchange for whatever he could desire, but eventually cannot exist without his immaterial shadow. And a note from Kierkegaard on a “reflexive melancholy”: It is this thoughtful grief that I intend to evoke and, as much as possible, to illustrate with some examples. I call them shadows, to remind by this name that I borrows them from the dark side of life and because, like shadows, they are not spontaneously visible (Google translation).

But I am not a theorist and prefer to talk about my works through episodes and encounters.

In the spring of 1990, a few months after the fall of the “iron curtain”, I went to Berlin to visit friends and remember walking through the Tiergarten to the sound of hundreds of hammers hitting what was left of the Wall.

During that same trip, I came upon a large flea market in the district of Potsdamerplatz, which became a huge wasteland being bombed during the Second World War. It seemed as if all the inhabitants of East Germany were there to sell off their few goods and especially their own histories. One could buy Soviet memorabilia, old sewing machines and bicycles, but mostly paper documents and family photos. It was at this point that the course of my artistic work changed, and I started working on found images and documents.

My first major installation, Aschenglorie (13-14), comprised pieces collected in Potsdamerplatz, while the following (Vanitas (15-16), Über die Schädelnerven (17-18) did more intentionally use images from archives of psychiatrists or other types of doctors. I also used numerous x-rays plates in those years. I considered x-rays to be both a form of writing of the body and a translucent, negative screen through which the viewer can distinguish, and possibly decipher, the image.

We reached the year 1997, but we forgot to mention globally important event: the fall of the Berlin Wall. How did it affect you, politically and artistically?

As I mentioned previously in the anecdote regarding the Potsdamerplatz flea market, 1989 marked the return of History with a capital H in my work, along with the use of photography, which can be considered the principal witness of last events of the last century. Henceforth, Communism was a thing of the past.

Politically, it was the myth of Communism itself, apart from its much frequent totalitarian drifts, which was shattered. To see TV images of hordes of people fleeing their country, like today’s refugees, had a tremendous symbolic impact. The choice I made in 1977 to cease direct political involvement and do what I can do by myself and along with a group of friends was somehow confirmed. And I continue to view artistic commitment as a form of political action. In fact it is an esthetical engagement: if it is good, it is art, and it is political to the extent that it can influence and change in people’s thoughts and feelings.

In this conversation, we have reached the last decade of the XX century. Many millenarianists and catastrophy believers have proclaimed that the end of the world is near and, as it relates to the Balkans, it would they might be correct: the JNA’s bombardment of Dubrovnik, the siege of Sarajevo (the longest in the history of modern warfare), the genocide in Bosnia… What is your feeling about the doomsday of our civilization?

Indeed, in the 1990s, we saw a return of warfare in Europe. We felt hopeless, powerless. European politicians did not help much, Americans were perhaps more effective, for the best and the worst. A well-known Italian writer obtained a truck driver’s license and transported food to Bosnia. A friend of mine died in a plane crash in the Croatian mountains, during a humanitarian mission. I didn’t have their courage, even though I didn’t have a family at the time.

I reacted as I felt: artistically. In a show in Rome in 1999, I presented an installation featuring enlarged photographs of various Italian historic monuments taken during Second World War in 1940. It was entitled Protection of the national artistic heritage from wartime aerial attacks. My intention was to highlight works of art that were covered with sandbags and scaffolding and removed from the gaze of spectators for whose benefit they had been conceived. They appear to us in the limbo of an announced catastrophe. (19-20)

In 2000, participating in a group show in Copenhagen called Models of Resistance, I requested UNESCO, the UN agency dealing with culture, to protect my own personal monuments, in accordance with the Hague Convention of 1954 concerning the protection of cultural property in the event of armed conflict. (21)

The same year, I presented another ‘political’ installation, a parachute asa sheltering space, where anyone could step in, get a glass of water or wine and find somebody to talk to. But as it was set up in the courtyard of an art institute, there was little likelihood that a “real” refugee would participate. (22-23)

A couple of years later I presented in my studio in Paris an installation entitled Four Theses on the Aesthetics of Fascism. There was L’art de la guerre (the work on the wrapped Roman monuments mentioned previously) but also pieces mentioning Albert Speer’s aesthetics of the ruins (the Ruinenwerttheorie) and others about the Balilla, the children from six to twelve years old who were inducted into the numerous paramilitary units under Italian fascism.

The New Millennium kicked off with a possible technological error related to our computers – the Millennium Bug. But the real problem was rather an Anthropological Error, built in our species – humankind was evidently going astray, lost on self-destroying path… What can artists do as times get hard?

I have three children and I feel the responsibility of the burden I am leaving them. They will face hard times or maybe only their grandchildren will go through such times. They will have to fight, and I have no doubt that they will do it, because already they don’t accept the idea that “there is no alternative”. I doubt that the alternative will be raising goats on a pristine mountain, even though that could also be possible. At the same time, I doubt that creating works of art represents a form of resistance to the world as it is. It is simply a matter of scale and audience. A work of art doesn’t reach a large enough public to move things. It is a form of witnessing, which is also necessary for me.

Works of art don’t save lives. Maybe I should have obtained a truck driver’s license.

Woke up this morning to the news that Peter Handke has won the Nobel Prize in Literature this year! Sir Salman Rushdie named Handke “Moron of the Year” in an article for The Guardian in 1999 for his “series of impassioned apologias for the genocidal regime of Slobodan Milosevic”. Your thoughts on official prizes and awards?

I too was surprised. Handke was a great writer in the 1970s, and then I don’t know what happened to him. Usually the literature Nobel prize is rather political and awards authors somehow in the opposition (like Dario Fo in Italy, when Berlusconi was prime minister). I don’t understand this recent decision. Next question please.

Let us know talk about the most recent period; when first encountered your work (via Internet). I remember, when I saw your photographs covered with X-ray images, I asked myself a question: “What would Hans Castorp, the main protagonist of the Thomas Mann’s novel The Magic Mountain, say if he had found such an artifact in his wallet instead of Madame Chauchat X-ray photo? The X-ray image from the novel was coming from the realm of Death (i.e. Medicine), yours from … What Source?”.

As I mentioned, I used X-rays images in my work as a language of the body itself and as a screen to blur vision. If we refer to bodies and signs, we mean anatomy; we speak of the body opening to allow the retrieval of signs. Therefore, such signs will make it possible to open up to the experience of other bodies and other things. Indeed, I positioned myself as an artist-anatomist.

My techniques (techniques are political) have always involved transpiercing the image, and I have been committed to “anamnestic responsibility”, which is neither an empty exaltation of memory, nor the evocation of pathos around historical horror.

My responsibility as an artist begins with the saturation of the image, in the contaminated field where the distinction between apology and denial, commemoration and refusal is unclear and undetermined. (24-29)

But one must mistrust the need to “say”; one should trust oneself and his own history and just continue doing what has to be done, with no intentions and little reflection. I hope that I have been succeeded in just doing that. (30)

(Thanks to Riccardo Lo Giudice for his linguistic skills)

.