.

.

“E sapeva d’altra parte che non si può frantumare una tradizione in modo più efficace che estraendone ciò che è prezioso e raro: i coralli e le perle. “ *

Uno. Findlinge.

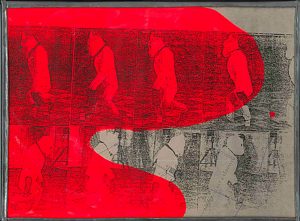

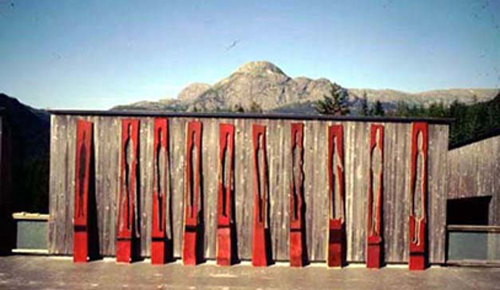

(1990, Krempelmarkt Potsdamerplatz, Foto Thomas Gade)

(1990, Krempelmarkt Potsdamerplatz, Foto Thomas Gade)

.

Esiste una parola tedesca con due significati: “Findlinge”. Designa sia le rocce erratiche depositate dalle glaciazioni in territori di diverse nature geografiche e i “trovatelli”. Questa doppia definizione non esiste né in francese né in italiano, nonostante si riferisca tanto a un oggetto trovato in un posto dove non dovrebbe essere, quanto a un essere abbandonato, raccolto e adottato.

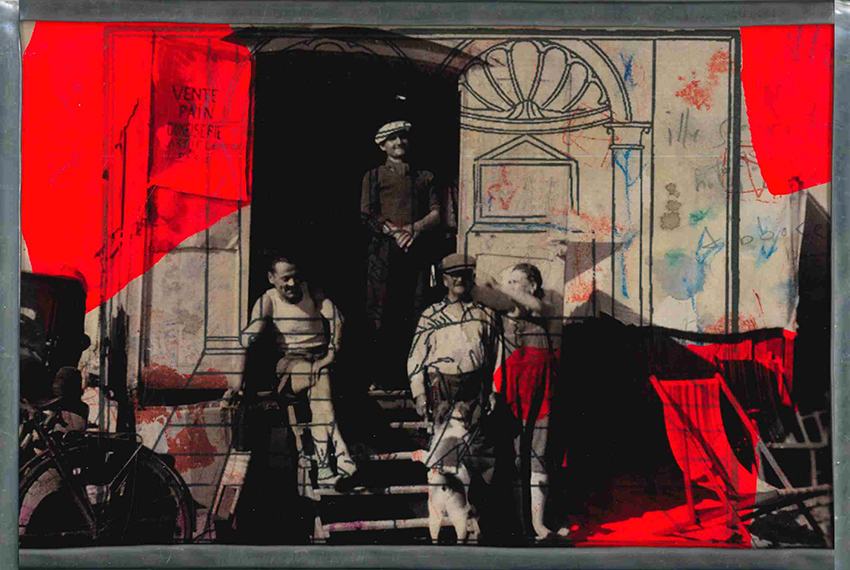

I turisti e i viaggiatori che avessero passeggiato per Berlino dopo la caduta del Muro (novembre 1989) sarebbero forse capitati sull’immenso mercatino dell’usato del quartiere della Postdamerplatz, diventato un gigantesco wasteland dopo i bombardamenti della Seconda Guerra Mondiale. Sembrava che tutti gli abitanti della Germania dell’Est si fossero radunati per vendere i loro pochi beni e, soprattutto, la loro propria storia. Si potevano comprare a pochi soldi apparecchi fotografici sovietici, vecchie macchine da cucire e biciclette arrugginite, ma anche tantissimi documenti cartacei e album di foto di famiglia. In questo luogo il corso del mio lavoro artistico cambiò, perché lì cominciai a lavorare direttamente sulle immagini e i documenti trovati.

.

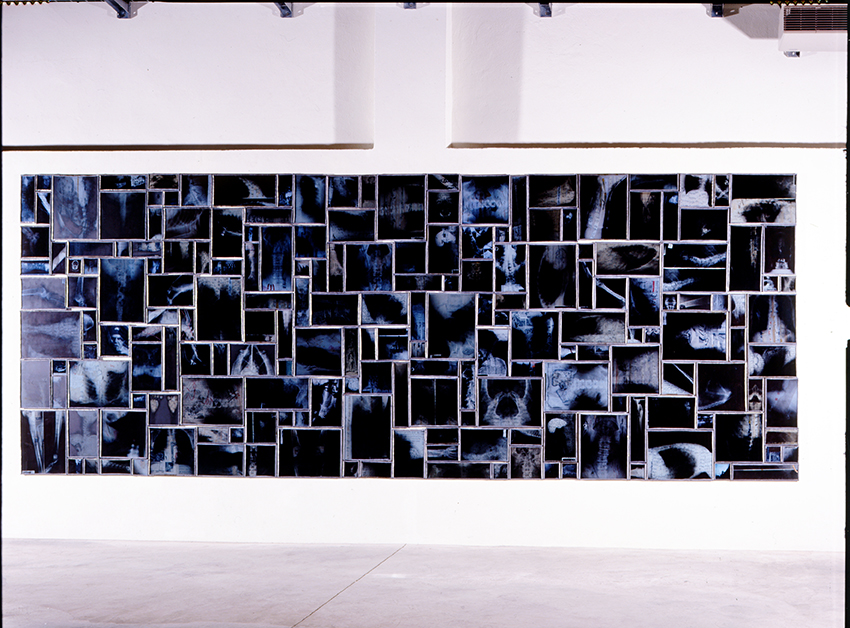

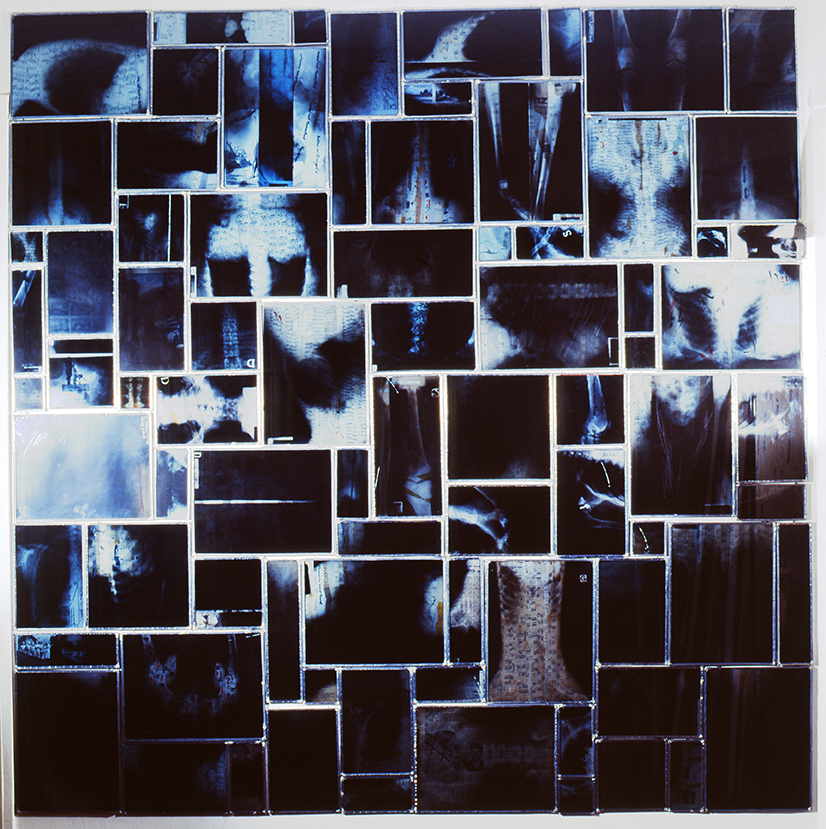

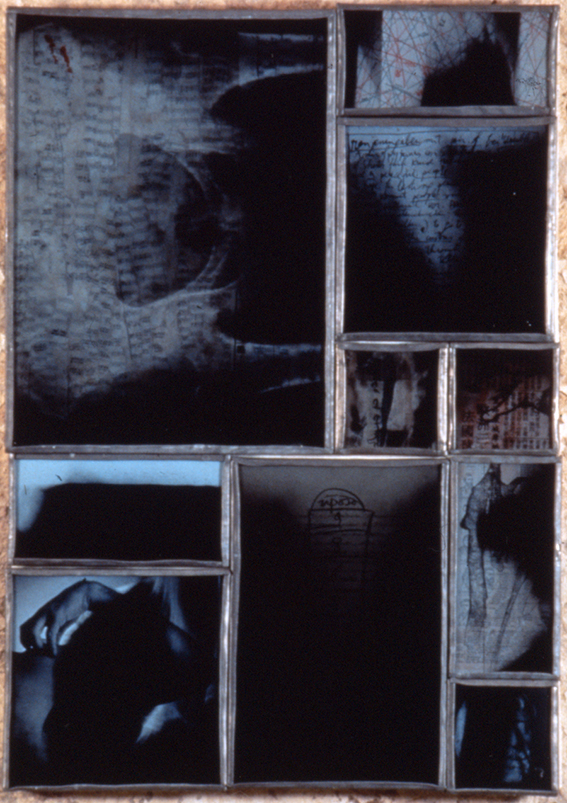

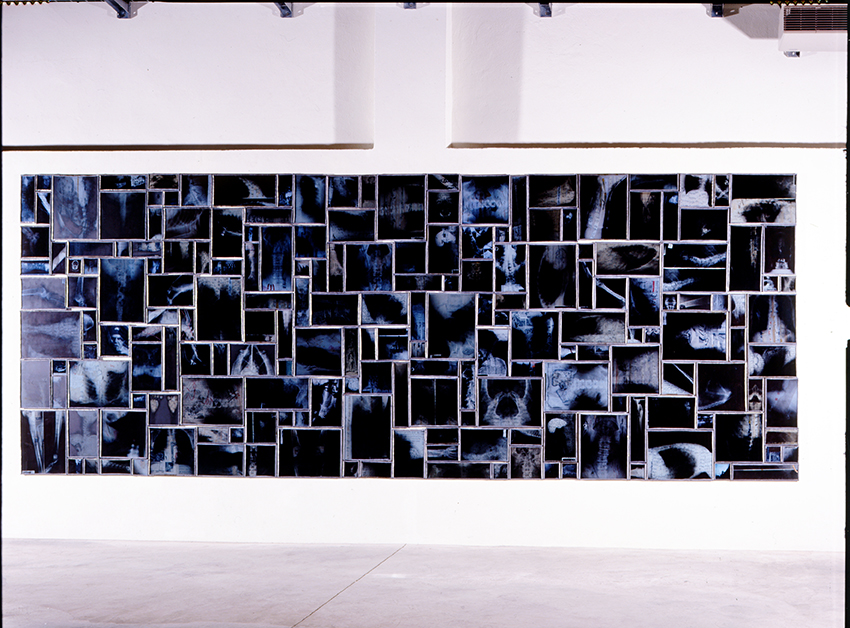

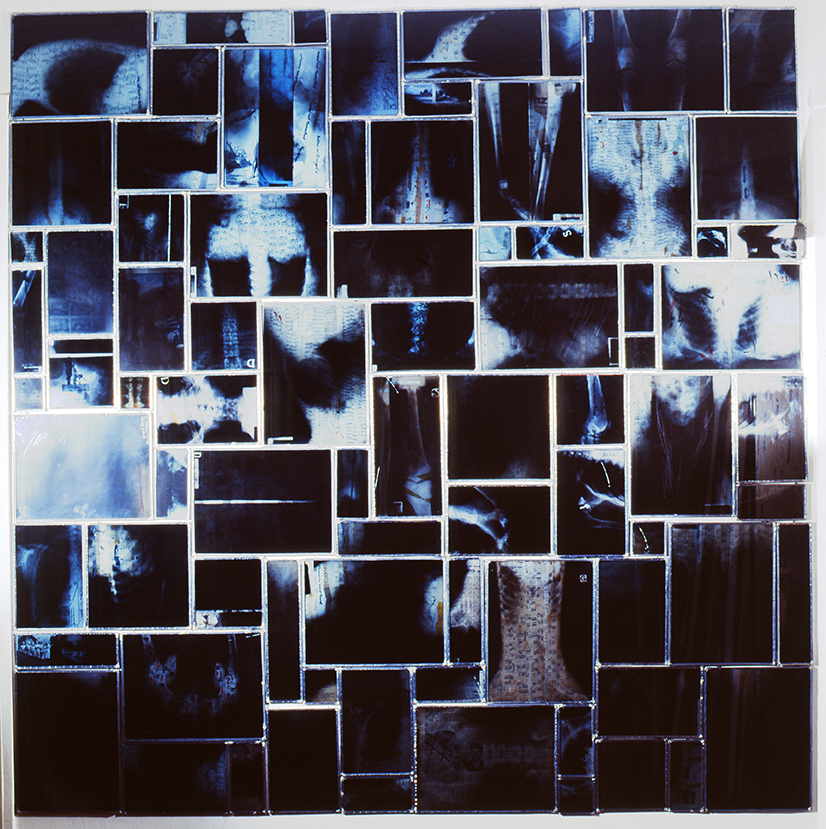

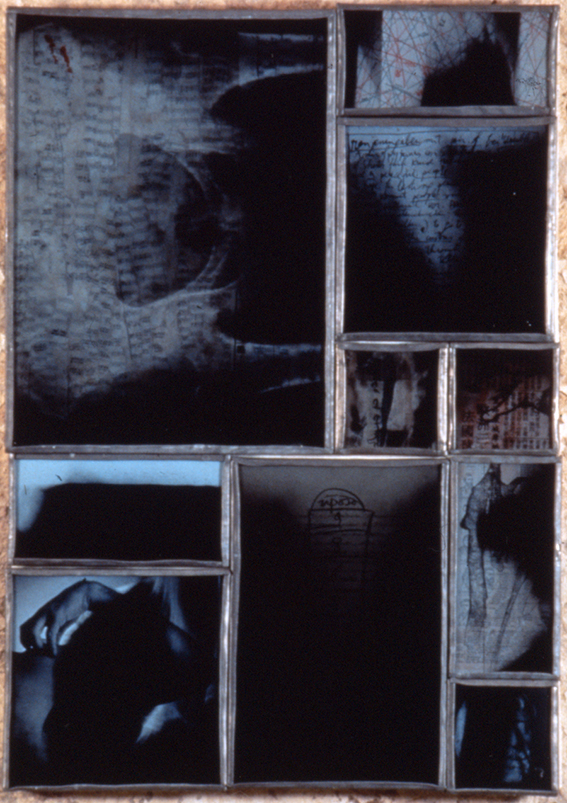

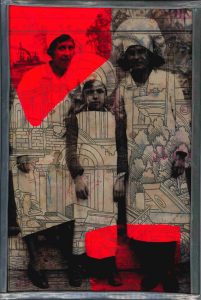

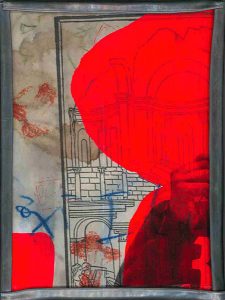

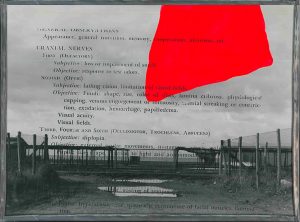

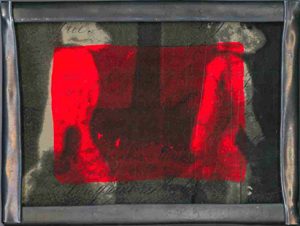

(1990-1993, Aschenglorie, Vanitas, Über die Schädelnerven)

(1990-1993, Aschenglorie, Vanitas, Über die Schädelnerven)

.

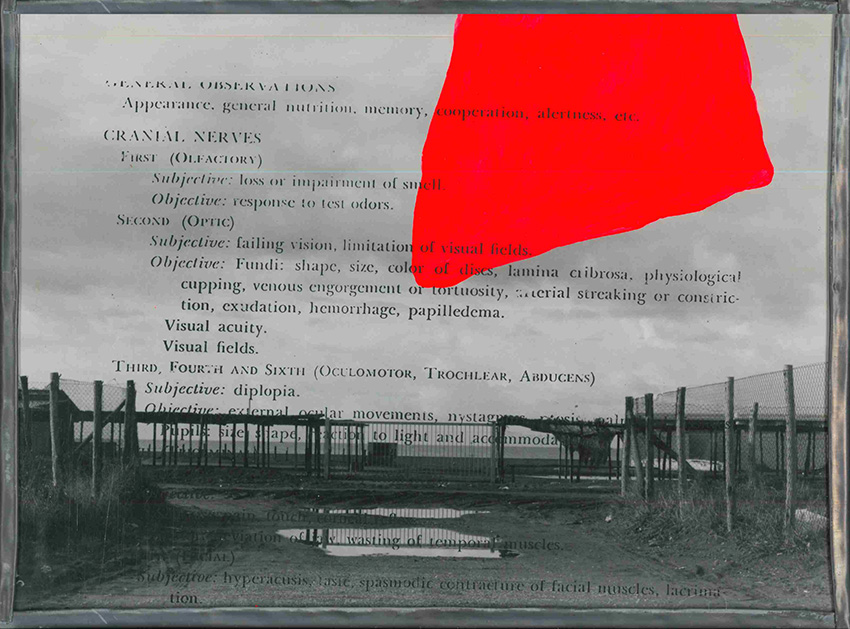

La mia prima grande installazione, Aschenglorie, è stata composta con pezzi raccolti alla Potsdamerplatz, mentre quelle successive (Über die Schädelnerven, Vanitas) erano basate più volutamente su immagini di archivi psichiatrici, o semplicemente medici. In quegli anni impiegavo lastre radiografiche. Per me, le lastre erano sia una scrittura propria del corpo umano, sia uno schermo traslucido attraverso il quale si poteva indovinare e tentare di decifrare l’immagine.

.

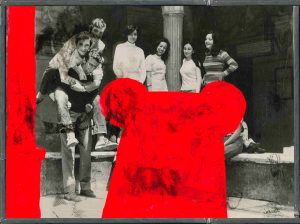

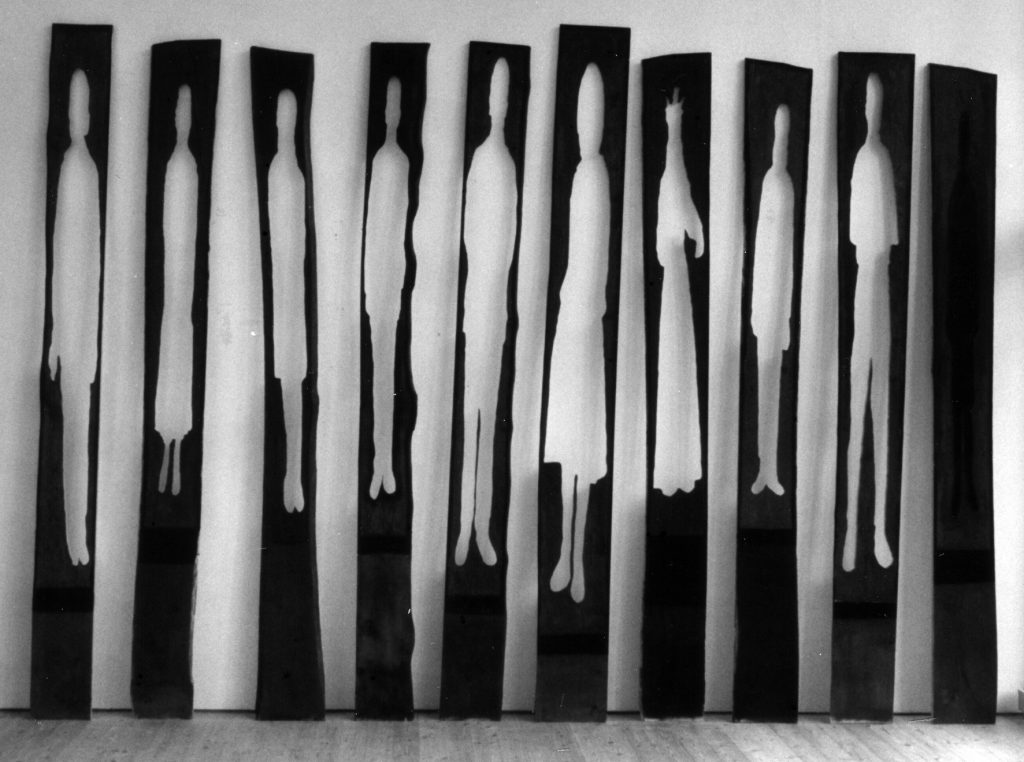

(2000, Skyggerids)

(2000, Skyggerids)

.

A quell’epoca ero molto interessato alla questione della traduzione tra testo e immagine. Ero sempre colpito da piccole frasi e citazioni che incontravo leggendo un libro. Una novella dello scrittore romantico Adelbert von Chamisso è rimasta con me per molti anni: la storia di Peter Schlemihl, che vende la sua ombra al diavolo in cambio di tutto ciò che potrebbe desiderare, ma che infine non può esistere senza questa cosa immateriale. Ma anche un commento di Sören Kierkegaard sulla “malinconia reflessiva”: “È questo dolore riflessivo che intendo evocare e, per quanto possibile, illustrare con alcuni esempi. Li chiamo tracciati d’ombra, per ricordare con questo nome che li prendo in prestito dal lato oscuro della vita e perché, come tracce d’ombra, non sono spontaneamente visibili”. La parola danese per queste figure è skyggerids.

.

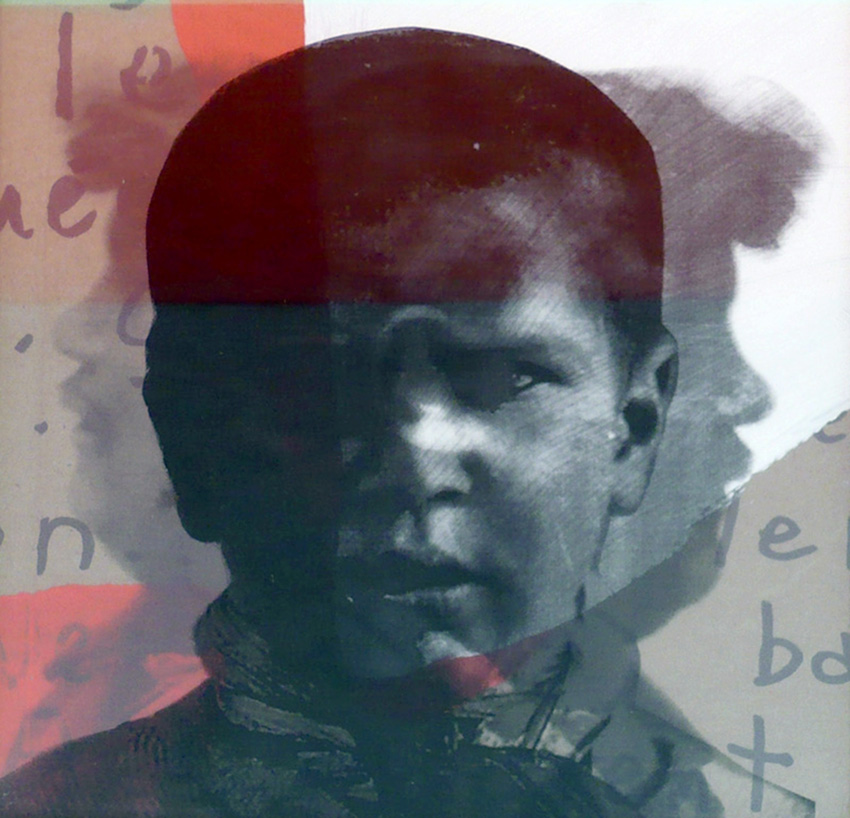

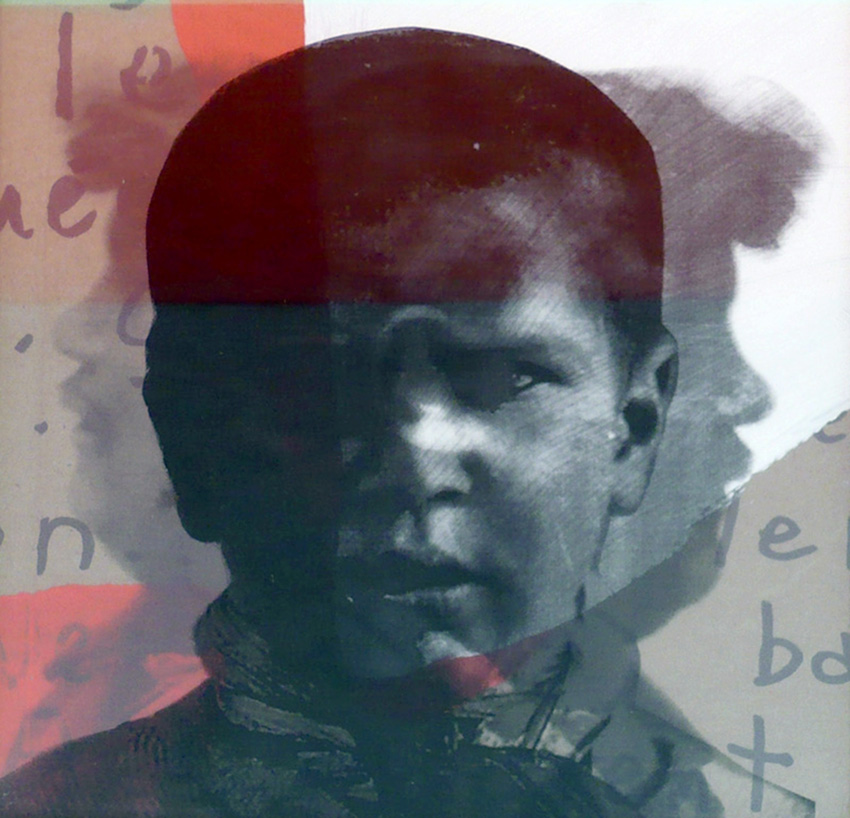

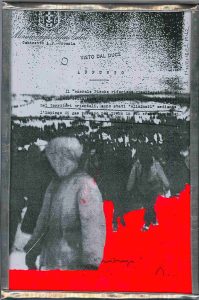

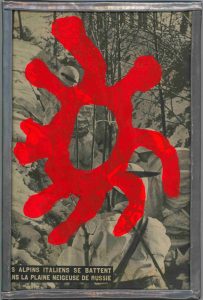

(1995, Ninna nanna)

(1995, Ninna nanna)

.

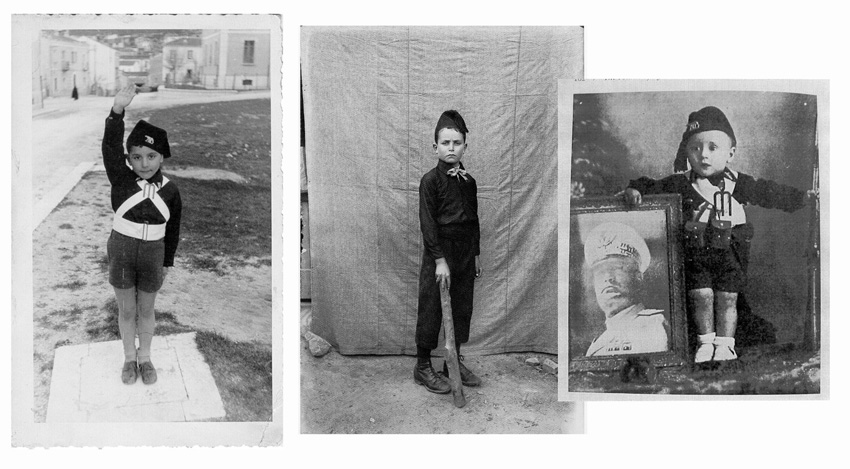

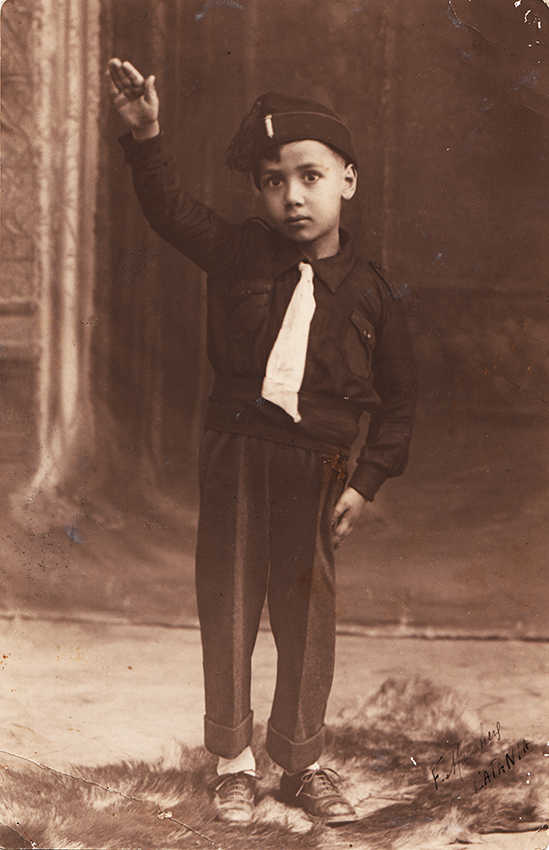

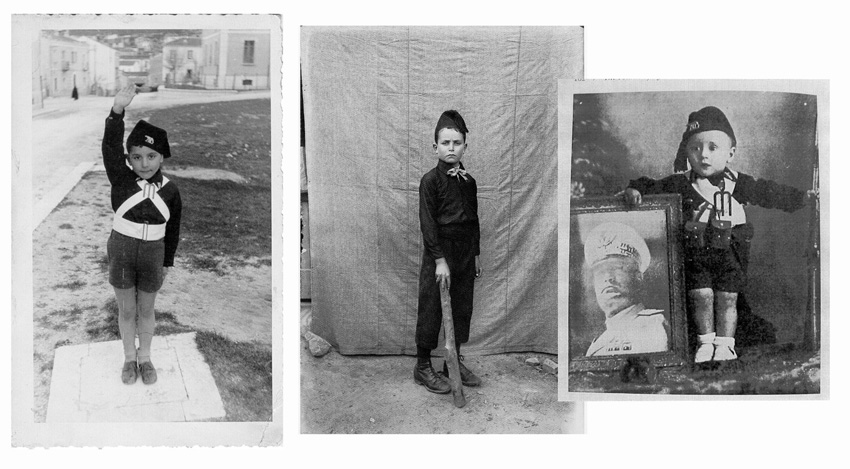

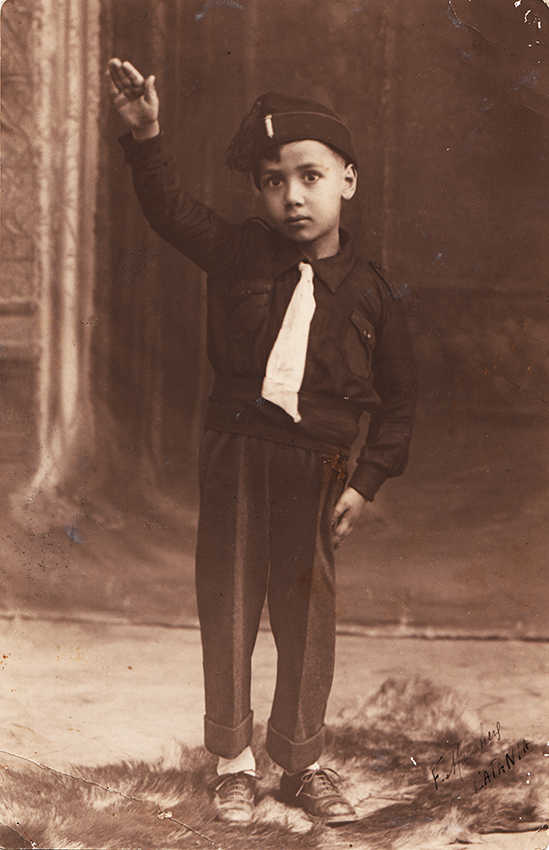

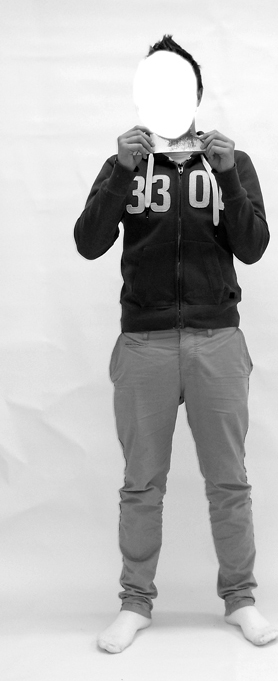

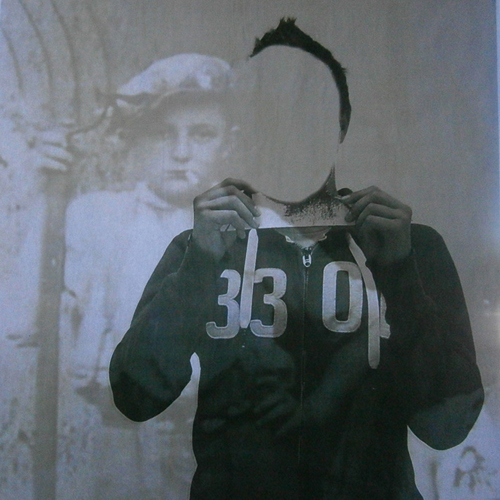

Ecco un altro lavoro sull’idea delle ombre che potrebbero rivelare qualcosa di inespresso. È basato su una singola fotografia, raffigurante un bambino negli anni 30 in un qualunque luogo d’Italia, espropriato da sé stesso, mostrato in un atteggiamento bellicoso che forse non poteva fare altro che adottare.

Nella posa fotografica (ovviamente, ogni immagine fotografica isola e iconizza il suo soggetto), il bambino è “promesso”, consegnato dagli adulti al regime che gli garantirà il futuro nel quale lo hanno iscritto. Qui avete tre variazioni sul tema: un bambino in uniforme che fa il saluto fascista; un bambino in uniforme con una mazza; un bambino in uniforme con un ritratto del Duce.

Questa tenerezza nel gesto di mettere il bambino davanti all’obiettivo fotografico, che è lo stesso in cui facciamo le foto dei nostri figli, è accompagnato da una premonizione: questo bambino, che è già un soldato, sarà dalla parte dei vincitori. La sua uniforme lo protegge già, e gli dà i riferimenti simbolici e ideologici della sua vita adulta.

.

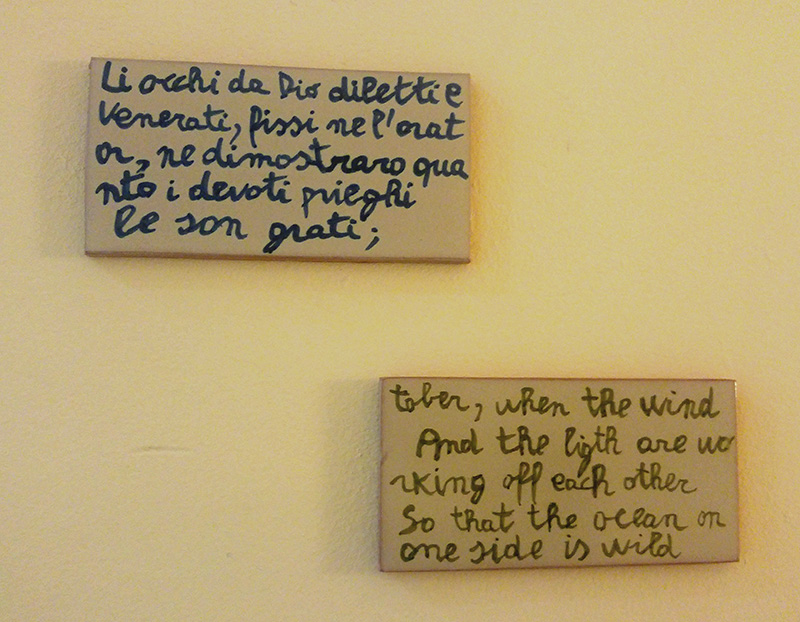

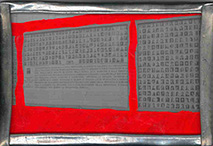

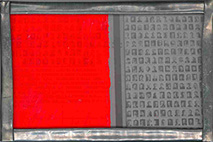

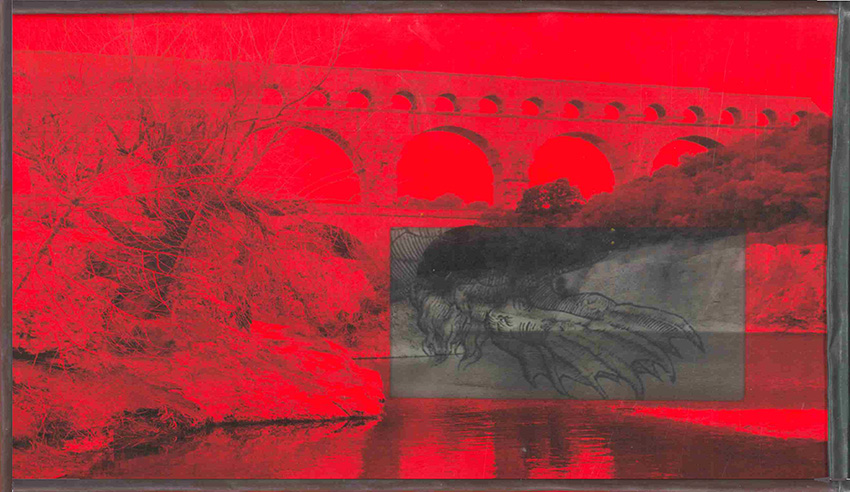

(2006, Ex voto)

(2006, Ex voto)

.

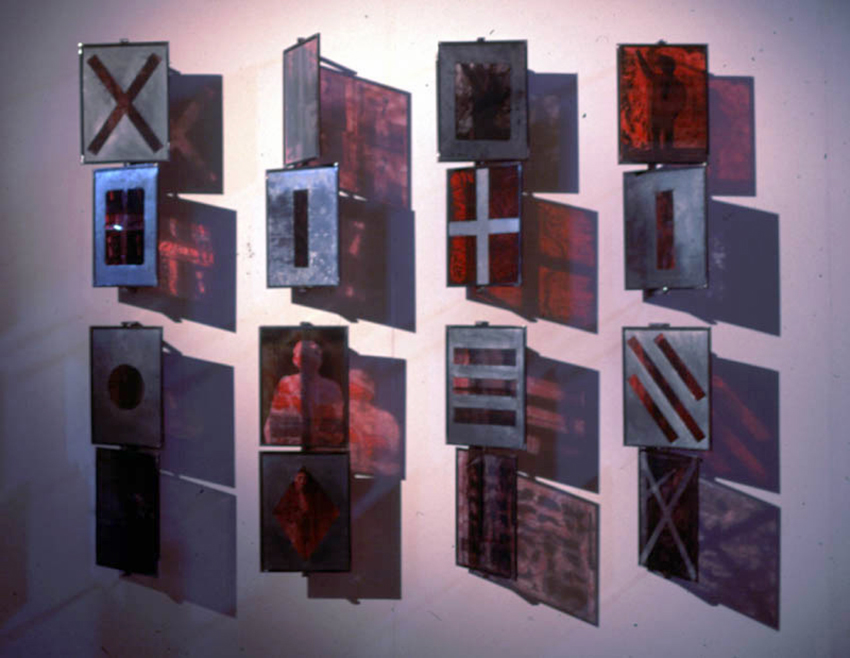

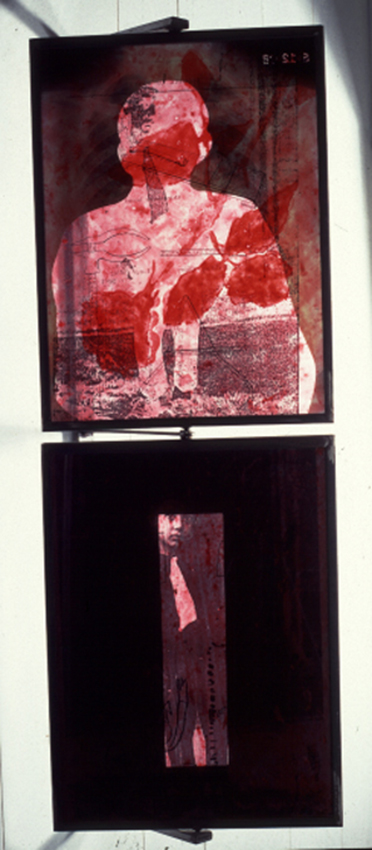

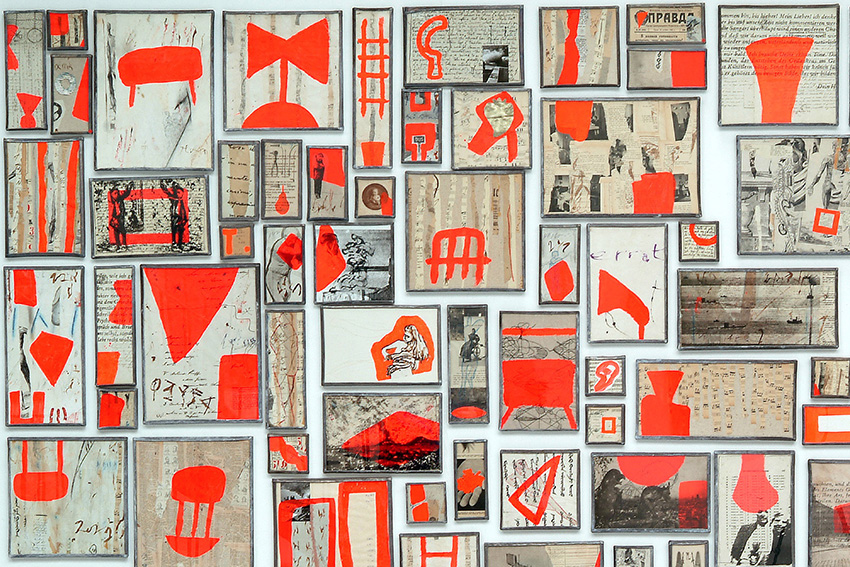

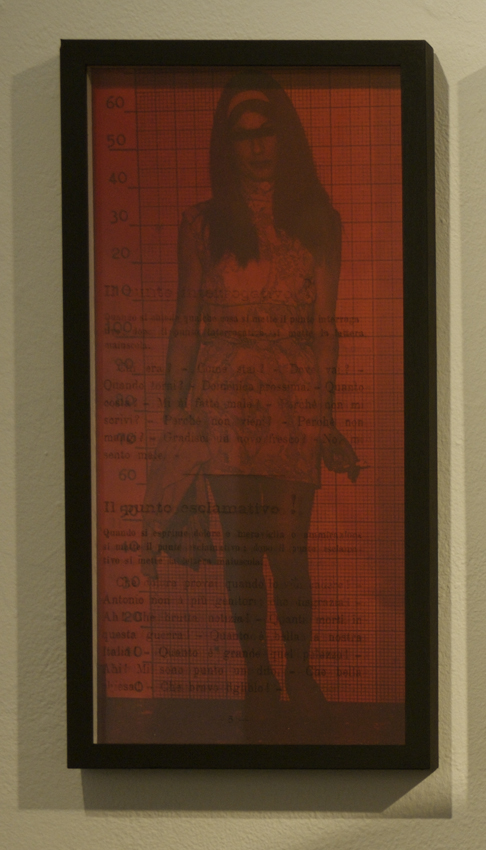

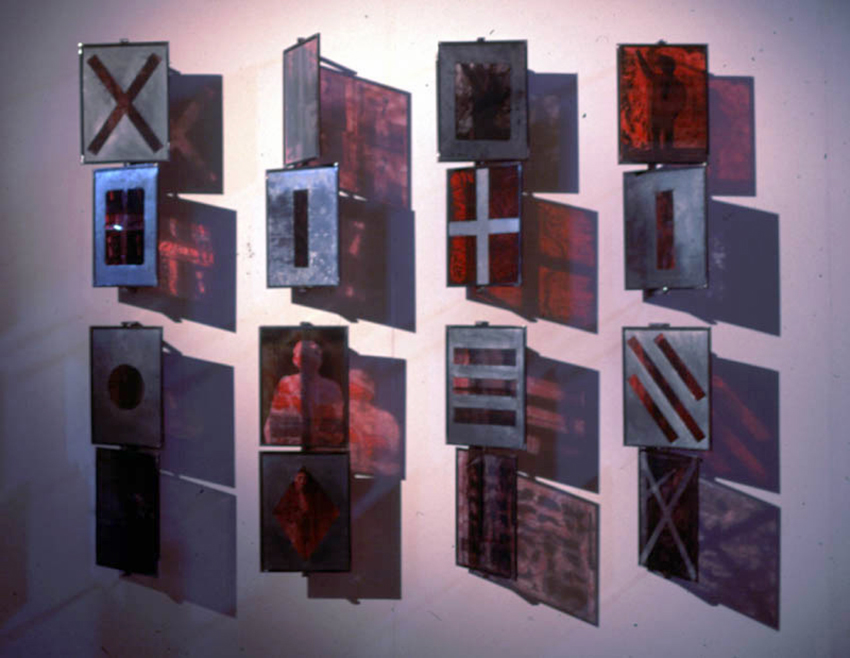

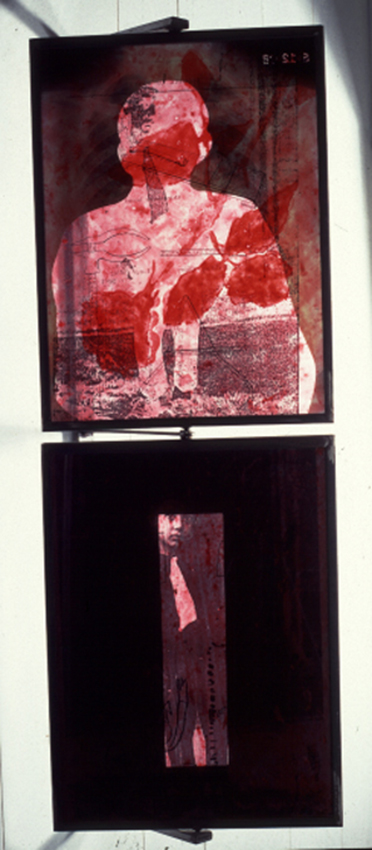

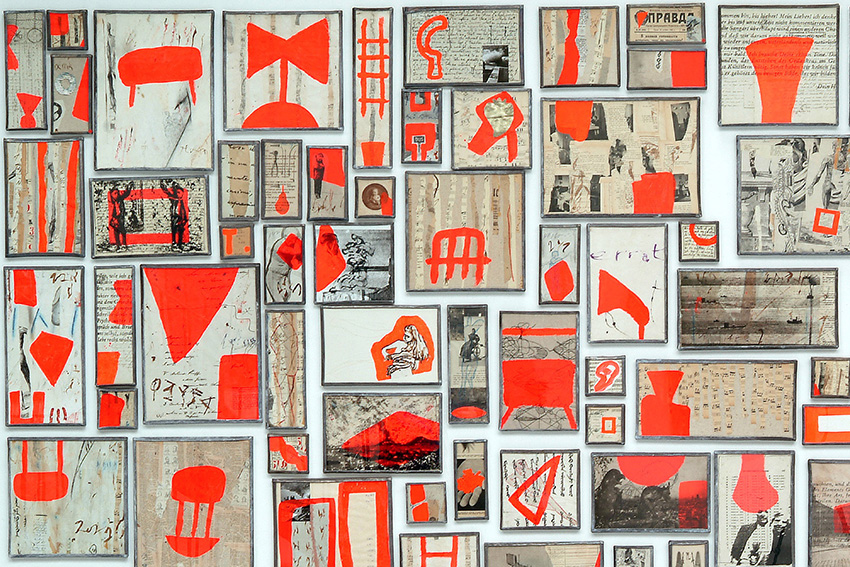

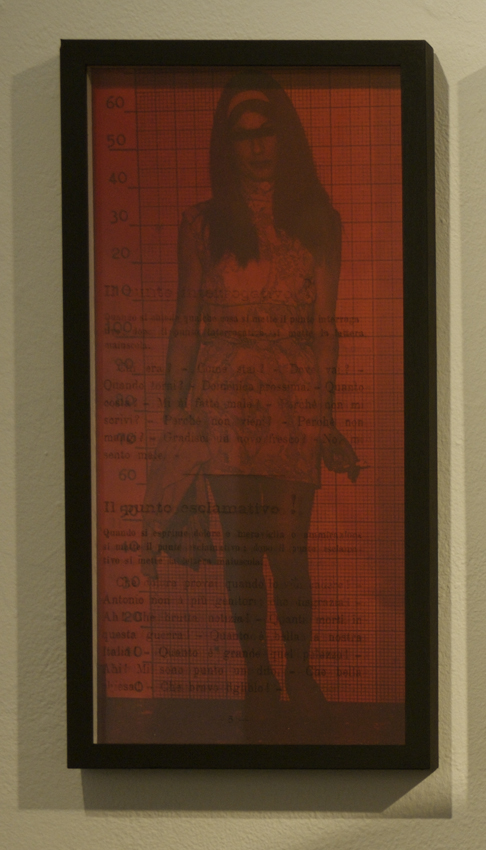

Nel lavoro denominato Ex voto, il cui ovvio riferimento sono le pareti delle chiese italiane rivestite di riproduzioni metalliche di organi o di pitture che descrivono incidenti o malattie da cui il fedele è guarito grazie ad un intervento divino, intervengo sul mio proprio materiale, disegni e documenti, così come farei su documenti trovati. La composizione a mosaico dà a significare che ogni pezzo, anche se unico, non può vivere senza gli altri che lo circondano e che gli aggiungono un contenuto complementare. La cornice, costruita contemporaneamente al montaggio delle immagini, è un tutt’uno con la creazione. Per parlare chiaramente, sottraggo un elemento figurativo al suo contesto per attribuirgliene un altro, sempre provvisorio.

.

Tre. Identificazioni.

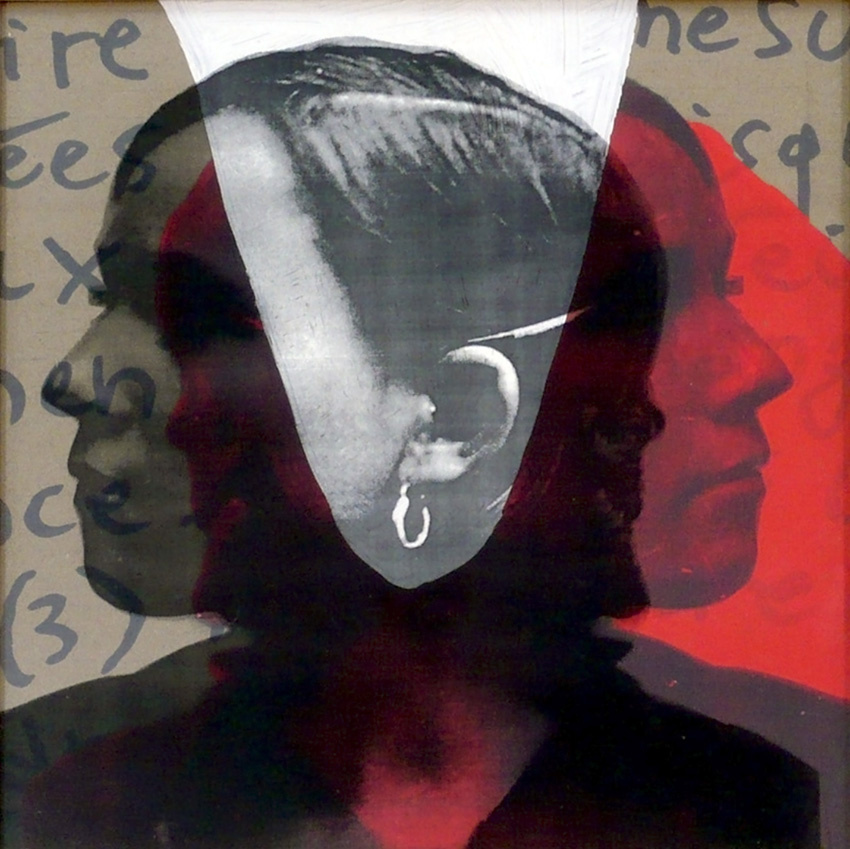

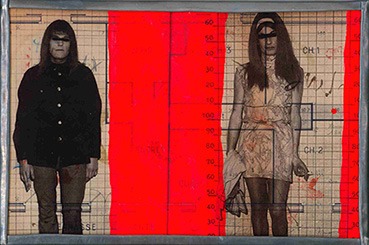

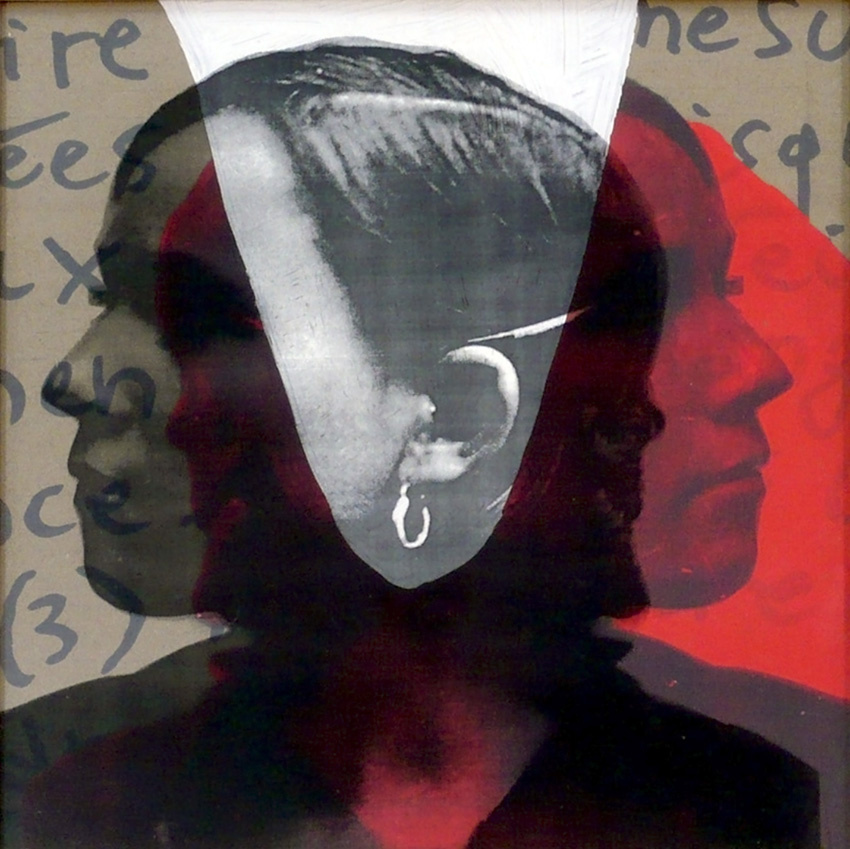

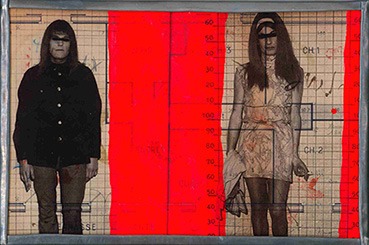

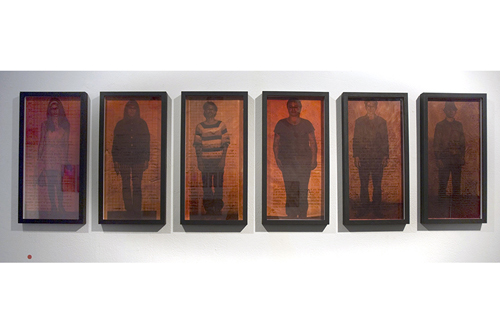

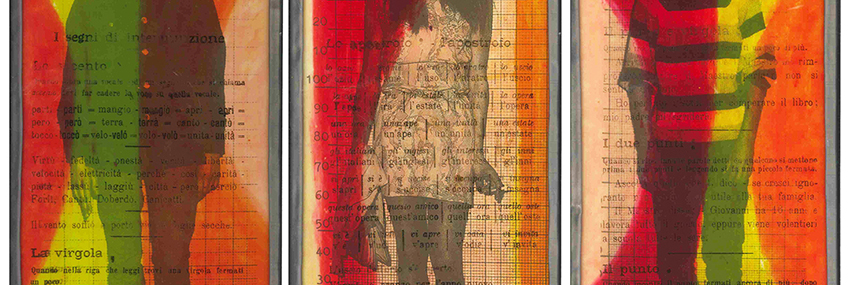

(2009, La Buoncostume suite et La Buoncostume/Wallflowers)

(2009, La Buoncostume suite et La Buoncostume/Wallflowers)

.

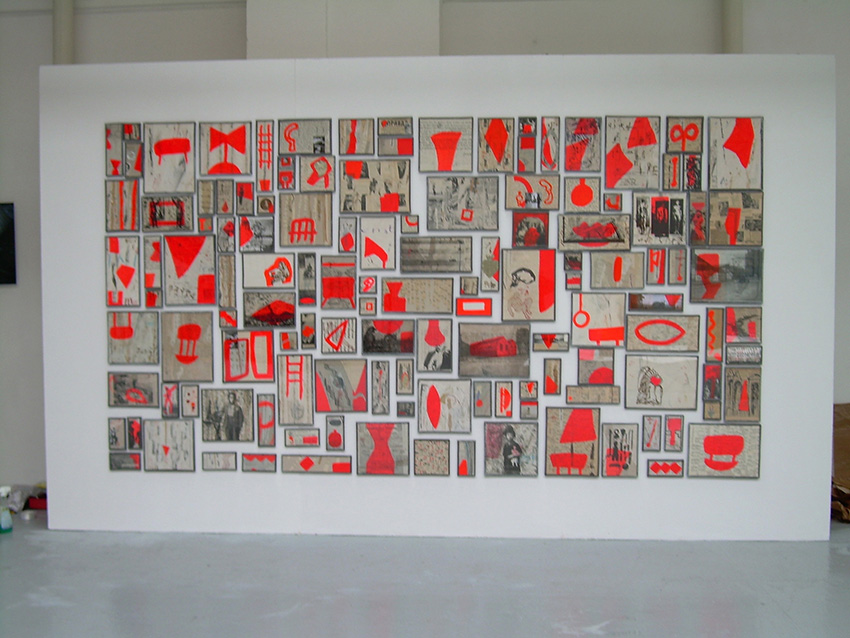

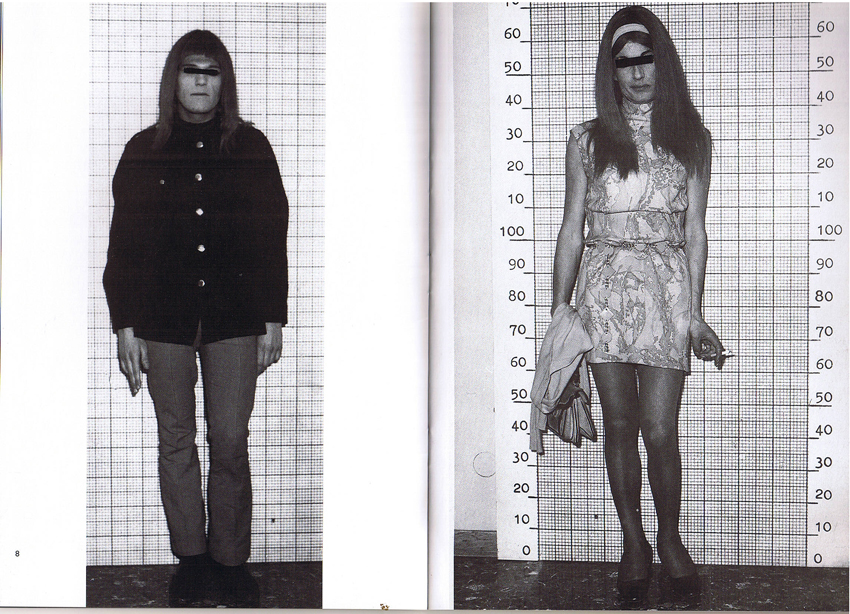

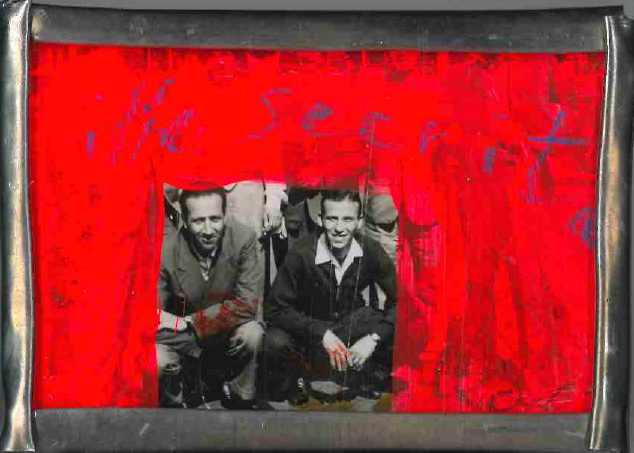

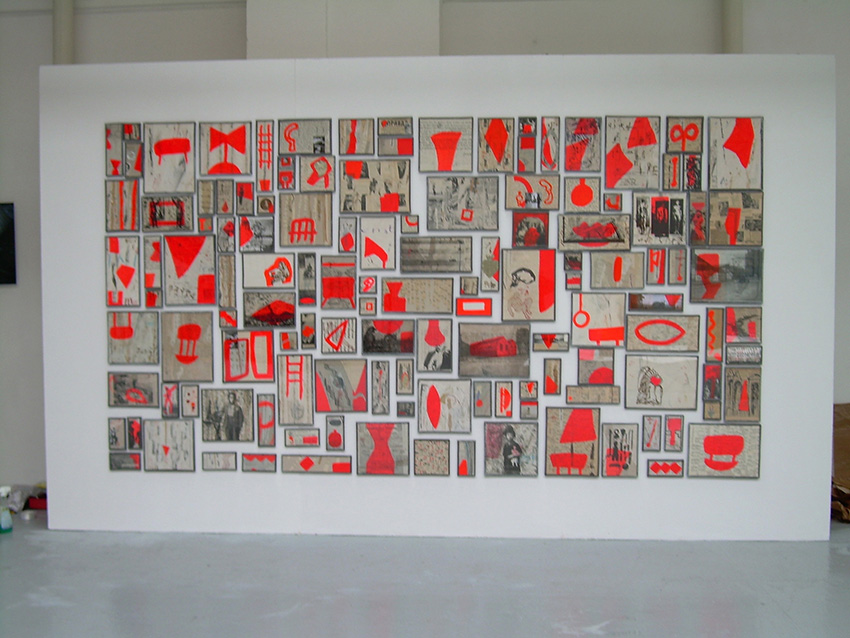

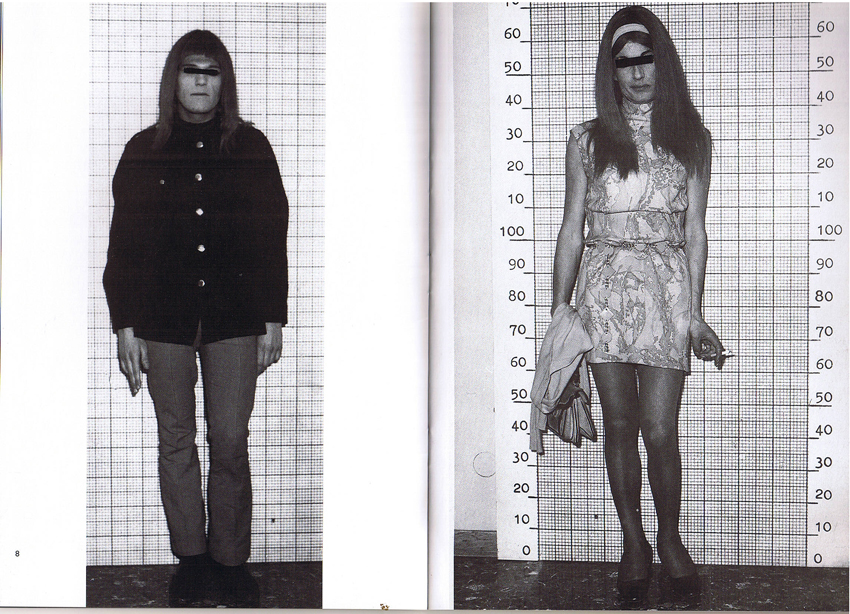

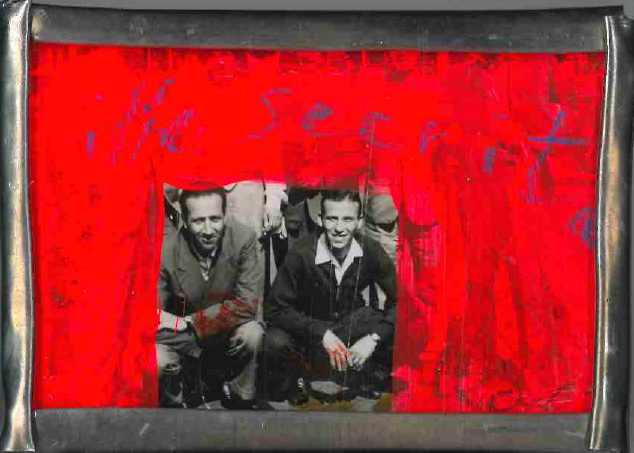

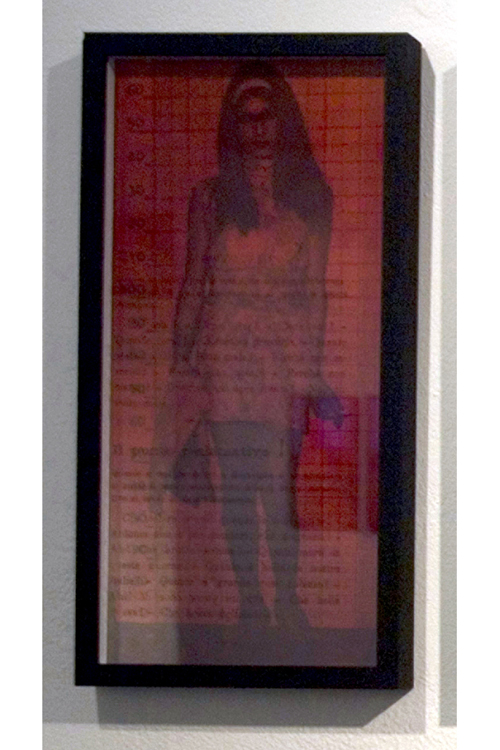

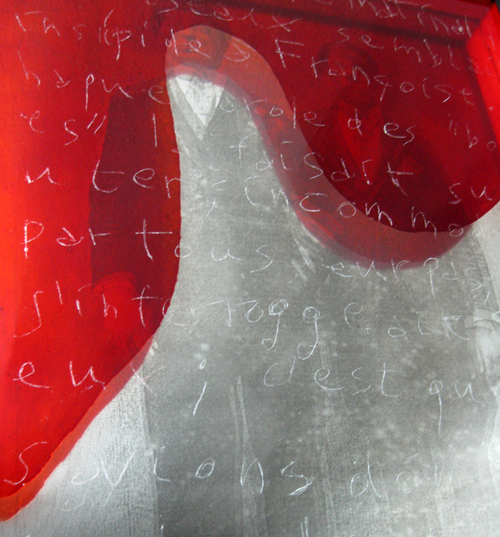

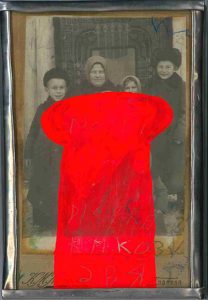

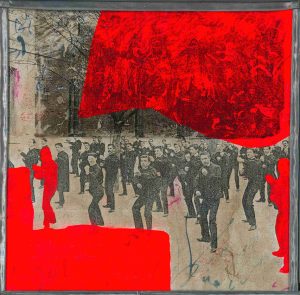

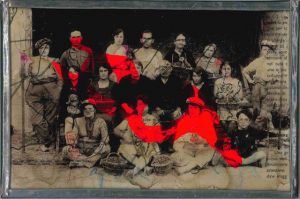

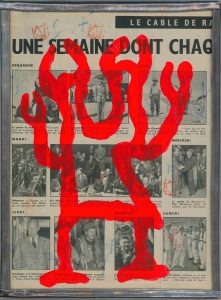

Nel gennaio del 2008 uno spazzino che lavorava nei pressi della Questura di Roma trovò due grossi sacchi della spazzatura ricolmi di fotografie: contenevano 8 000 immagini (di identificazione, sorveglianza, reperti) che, non essendo più di nessuna utilità per le investigazioni correnti, erano state gettate per liberare spazio, invece che essere depositate all’Archivio di Stato.

Le immagini recuperate dallo spazzino vennero acquisite dal Museo del Louvre, una galleria-libreria antiquaria, che ne preparò un’esposizione e trasmise l’informazione alla stampa. Ma il giorno stesso dell’inaugurazione, i Carabinieri, mandati dalla Sovrintendenza per i Beni Culturali e accompagnati da due archivisti, si presentarono alla galleria per sequestrare tutto il materiale esposto, insieme con il catalogo dell’esposizione. Un assistente del gallerista riuscì a intascare un solo esemplare del catalogo, e è da questo unico esemplare che ho recuperato sei immagini: provenivano probabilmente dalla squadra del Buoncostume e, a giudicare dai vestiti e dall’aspetto dei soggetti, potrebbero risalire alla fine degli anni 60.

Nel lavorare su tali immagini intendevo suggerire l’idea di una sfilata di moda, creando una sequenza non priva di una certa eleganza plastica. Con mezzi chimici ho trasferito sul vetro brani di un sillabario per la scuola popolare. Non c’è nessuna relazione tra le diverse componenti del lavoro, se non quella imposta da me, più o meno consapevolmente.

Sono abituato a lavorare in serie, per elaborare più varianti alla soluzione di una domanda formale che mi sono posto. Nelle serie che qui mostro, ho affrontato la questione della posa e della frontalità che concerne sempre questo tipo di immagini (a questo proposito vorrei ricordare una differenza: mentre l’identità è una qualità o, meglio ancora, l’insieme delle qualità e delle relazioni che definiscono un individuo, l’identificazione è un processo, l’insieme degli atti di cui abbiamo bisogno per riconoscere un individuo tra gli altri).

In alcune di queste foto si possono vedere le griglie metriche che fanno da sfondo ai ritratti; mi ricordano le giovani che ‘’fanno parete’’ alle feste di villaggio, nell’attesa di essere invitate a ballare. In inglese sono chiamate wallflowers, lo stesso termine usato anche per descrivere una persona timida.

Vorrei sottolineare che, qui come in altre mie serie, lo sfondo, il passaggio del colore, le incisioni sulla superficie dell’immagine hanno la funzione di permettere altre possibilità di lettura. Semplicemente, un’altra dimensione.

.

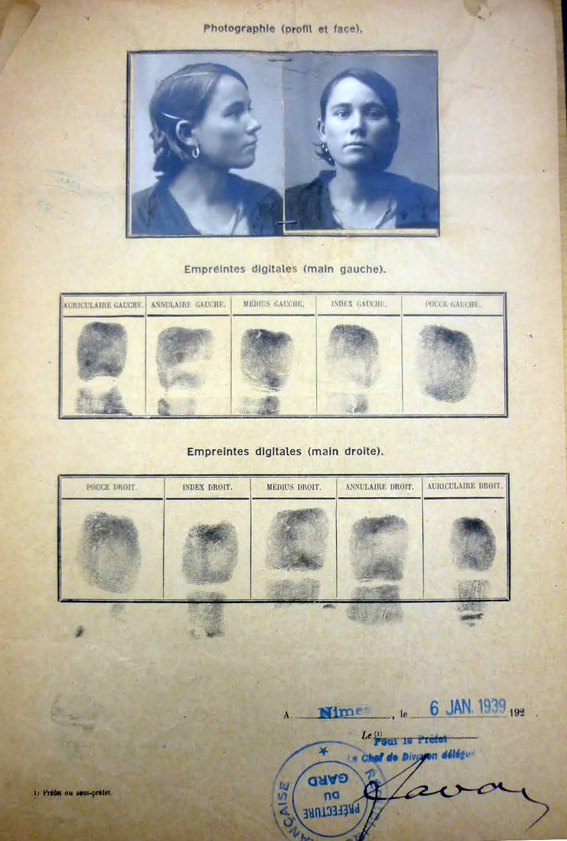

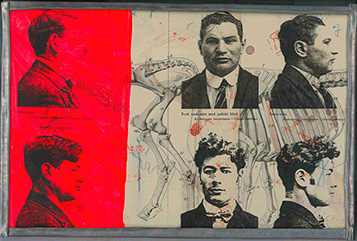

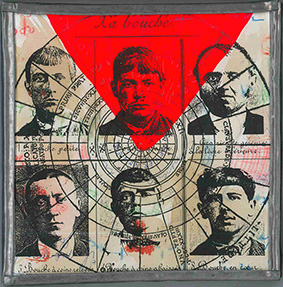

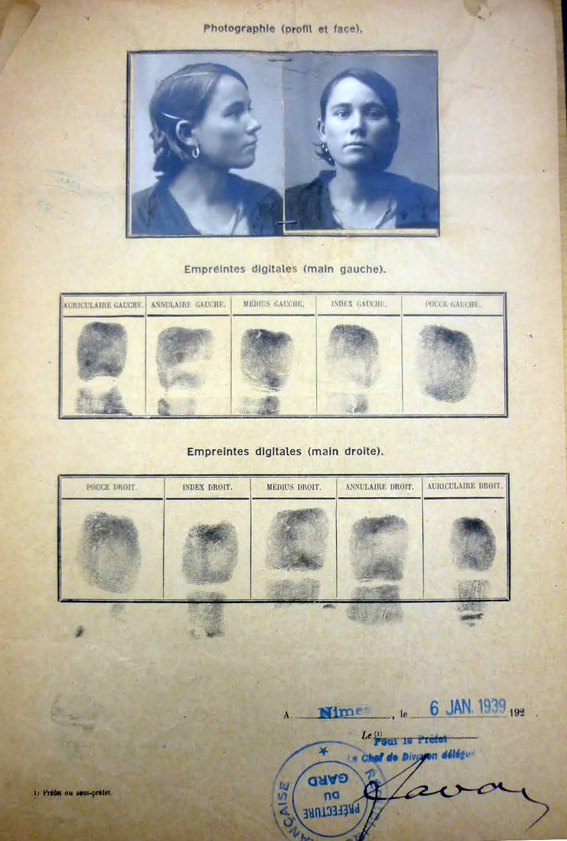

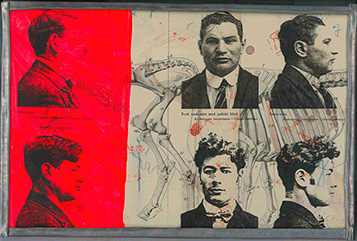

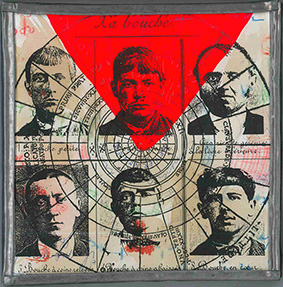

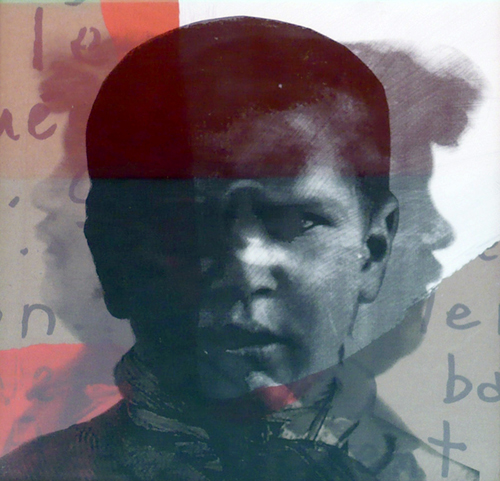

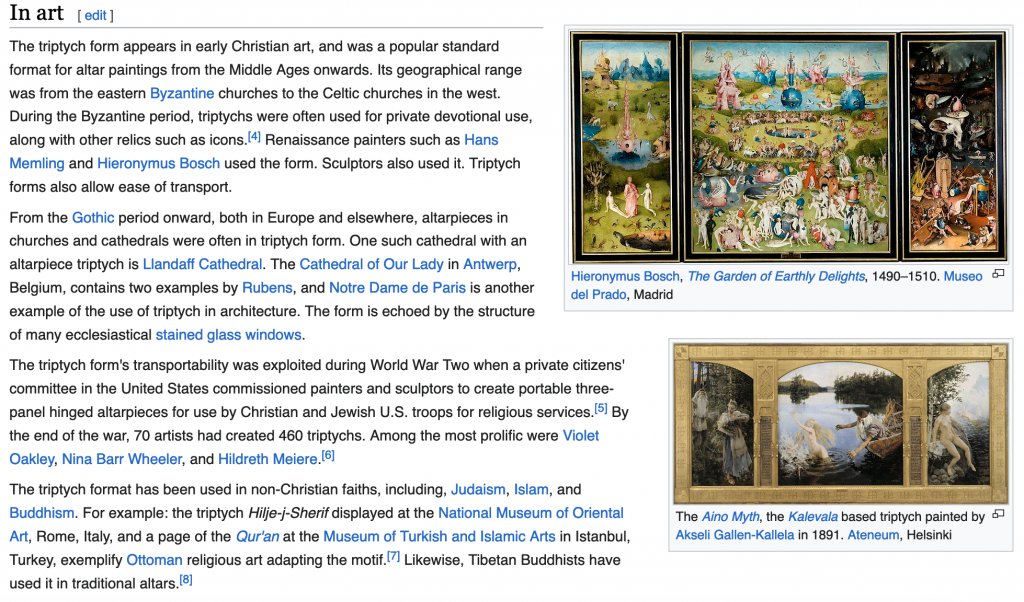

(2010, Leçons d’anthropométrie)

(2010, Leçons d’anthropométrie)

.

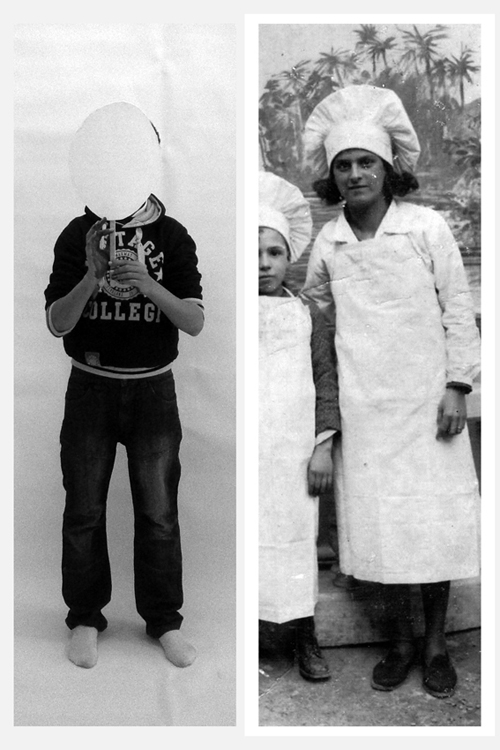

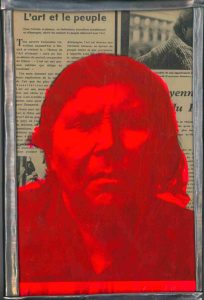

Questa serie è nata da una ricerca presso l’archivio del dipartimento del Gard (Sud della Francia). Ogni persona senza fissa dimora era tenuta a portare su di sé un lasciapassare antropometrico, redatto secondo gli standard dettati da Alphonse Bertillon (l’inventore dell’identikit), e timbrato ogni volta che entrava e usciva da un comune. Questo documento d’identità, il quale scopo era ovviamente quello di controllare la popolazione nomade, venne utilizzato fra il 1912 e il 1969: oltre ai dati personali conteneva le foto di fronte e di profilo del portatore, nonché le impronte delle dieci dita.

Ho riprodotto sei ritratti di membri di una stessa famiglia (fatte all’inizio degli anni 20) su vetro, e le ho sovrapposte ad articoli di legge istituenti i passaporti: ho trascritto questi articoli con un pennarello su cartoni ritagliati, come quelli esibiti dai mendicanti ai semafori.

Per confondere il processo di identificazione, ho sovrapposto una foto frontale a una foto di profilo oppure all’immagine di un familiare. Ho inoltre dipinto forme geometriche sul vetro, a ricordare i colori basici usati nella Bauhaus o nel costruttivismo russo.

.

Quattro. Millenovecento.

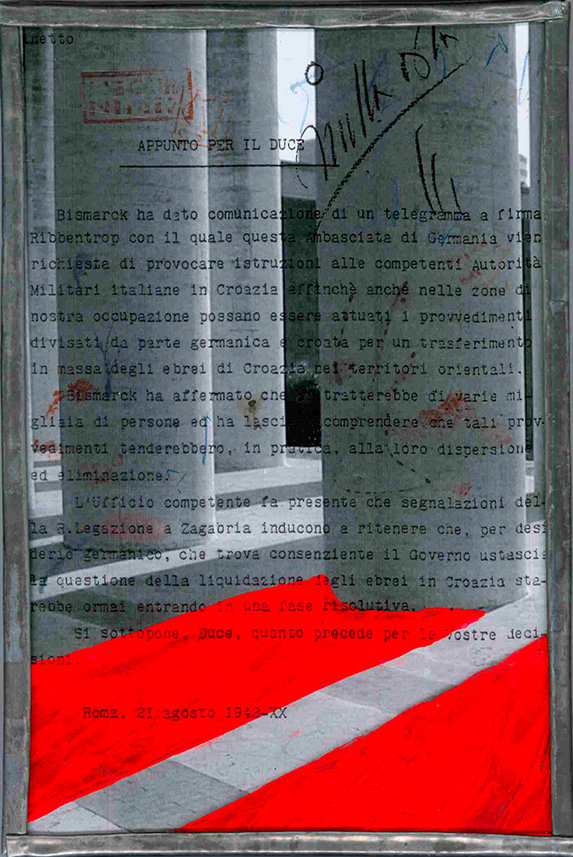

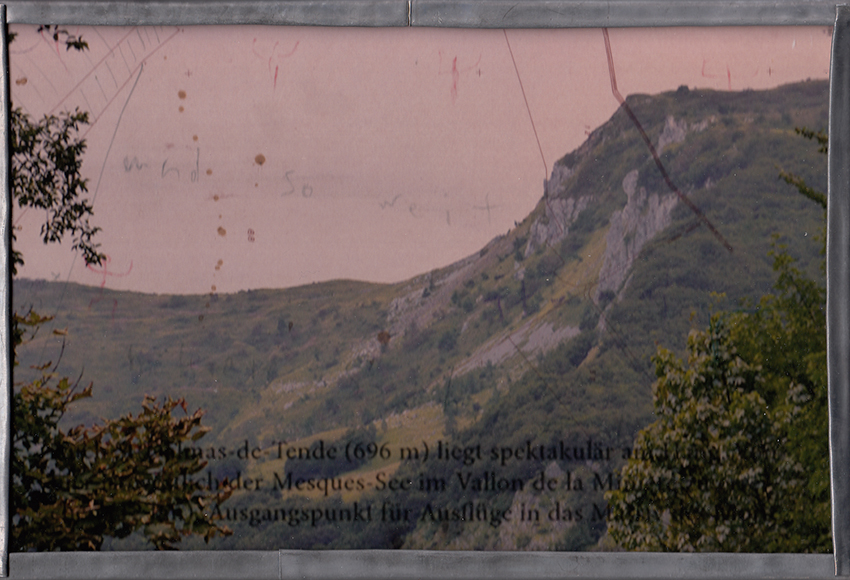

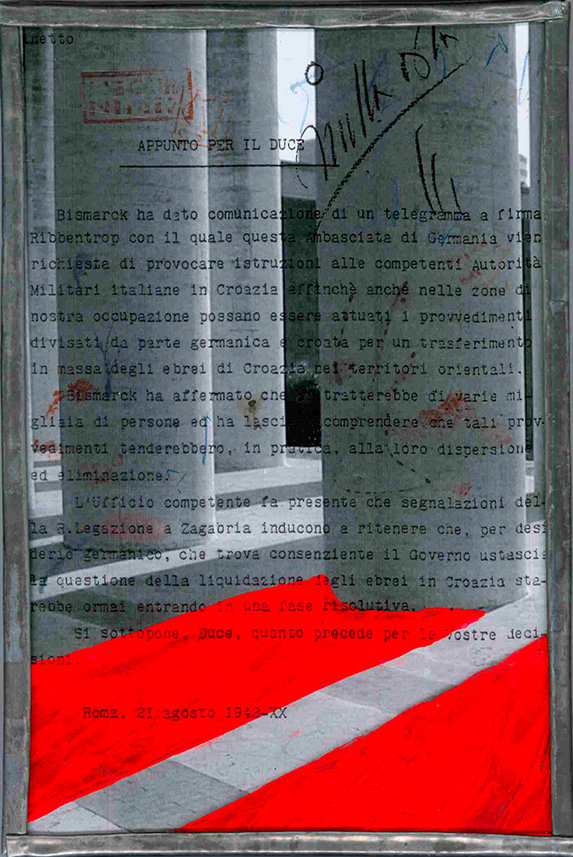

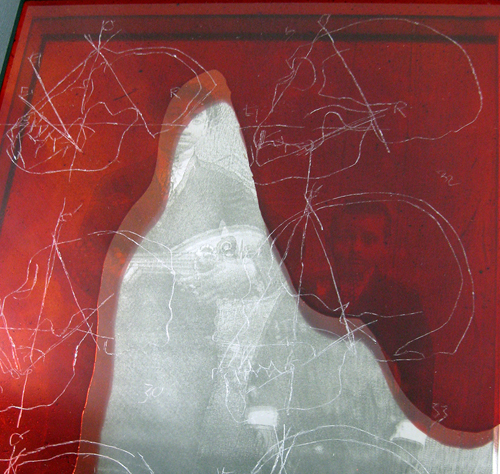

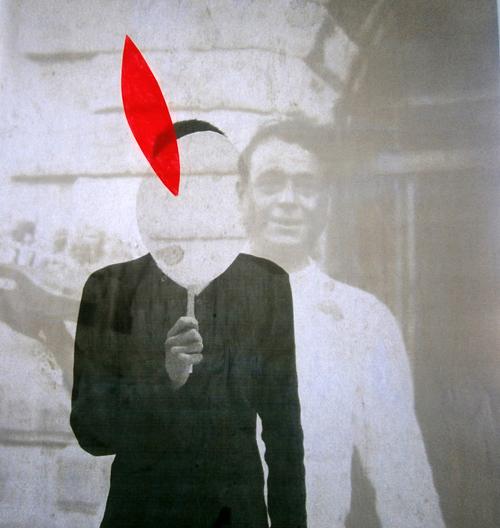

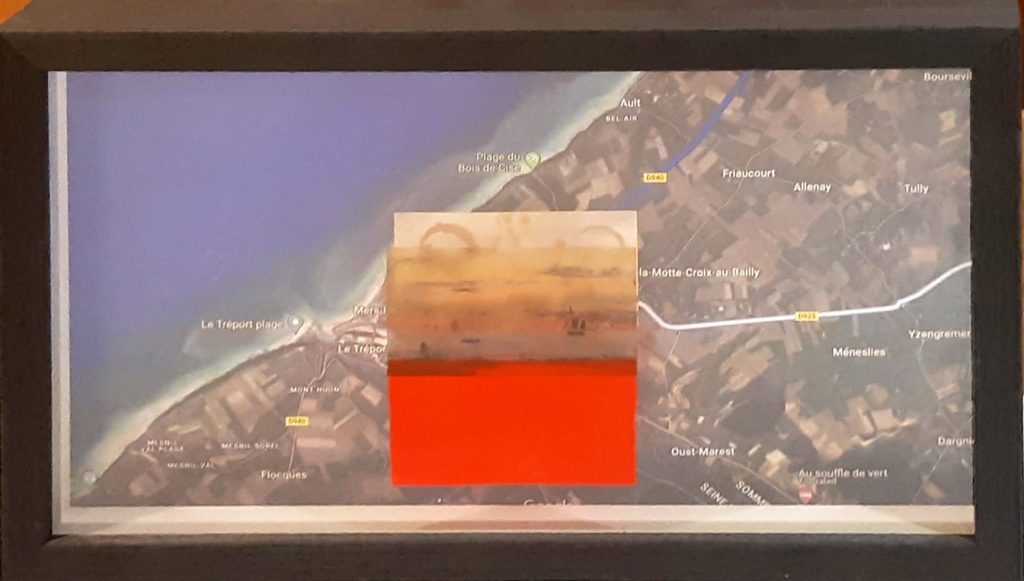

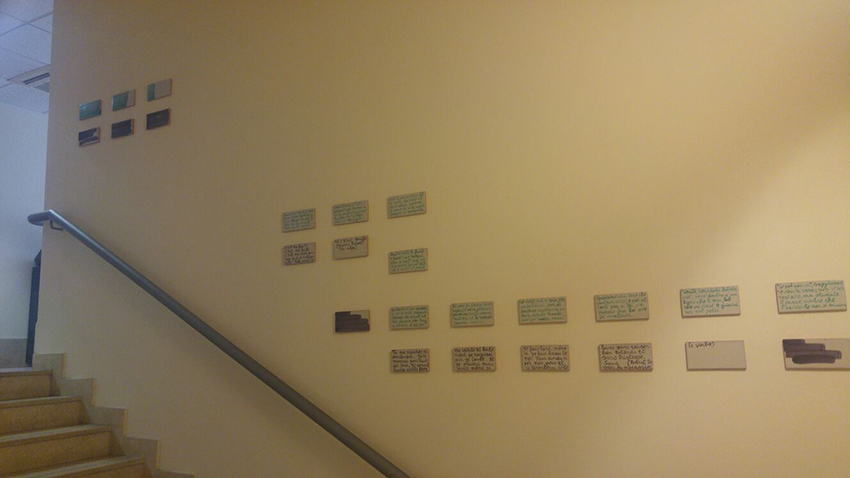

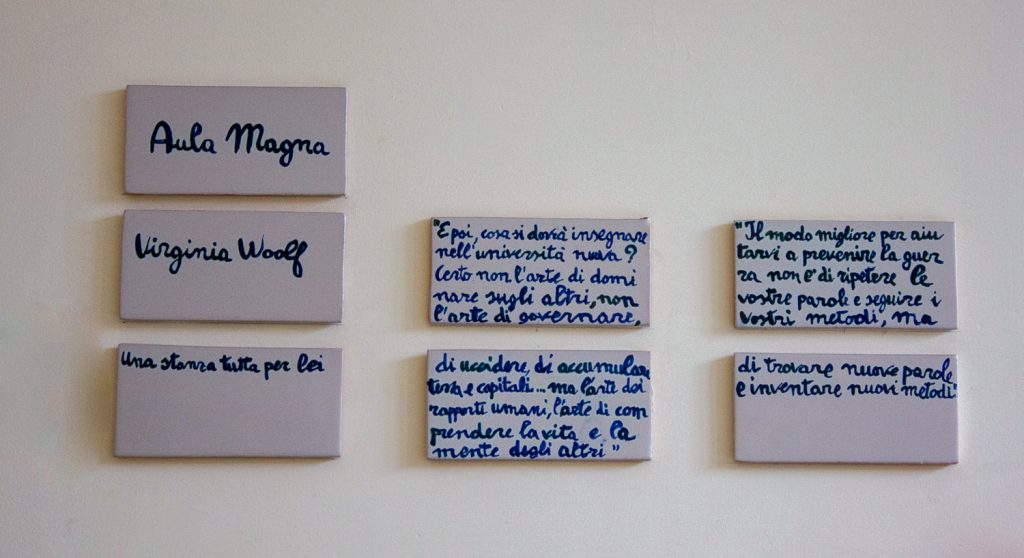

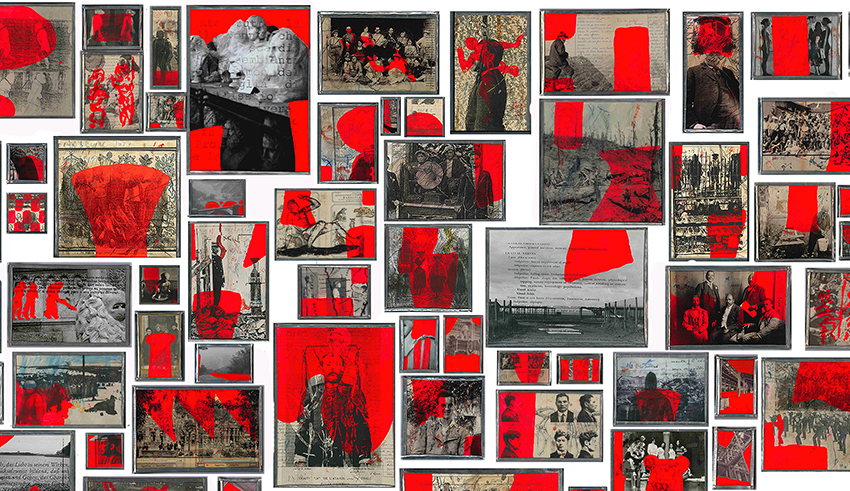

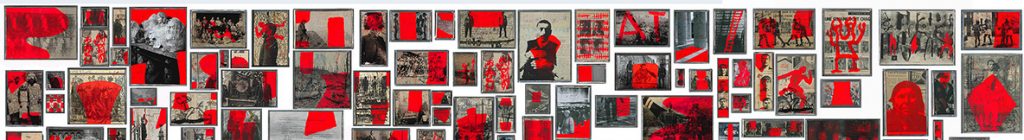

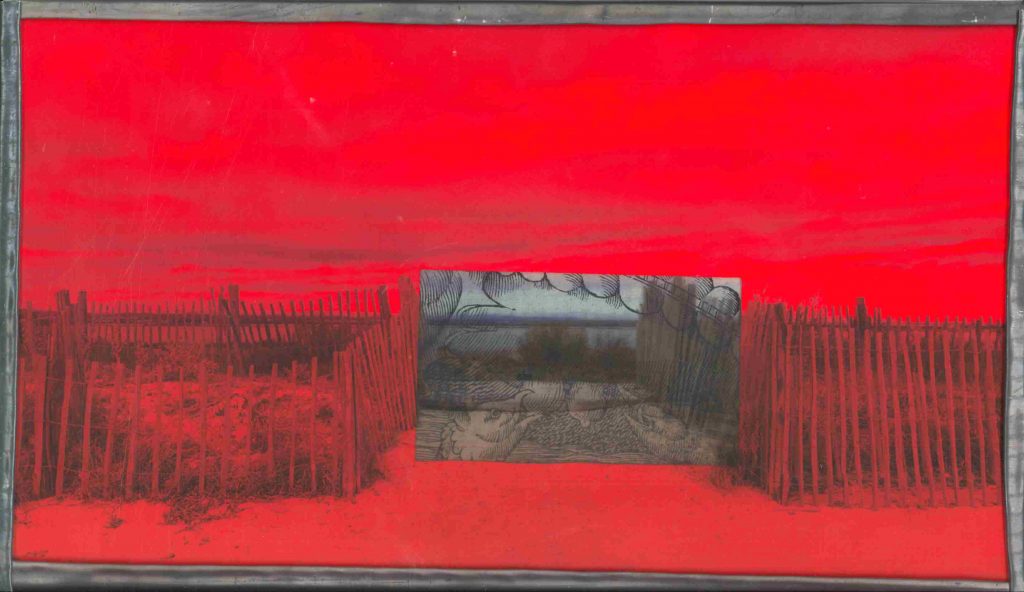

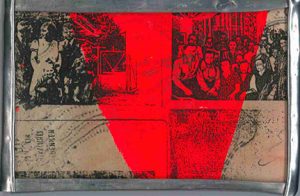

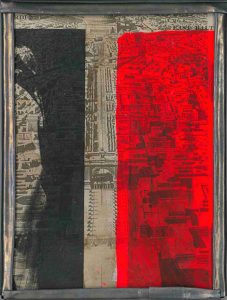

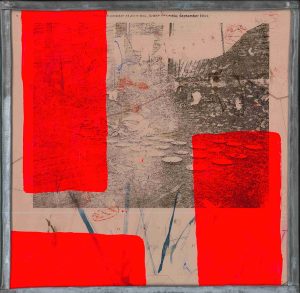

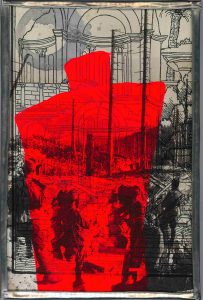

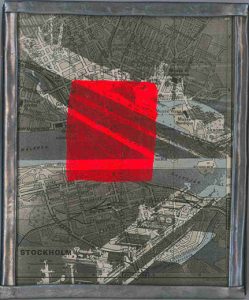

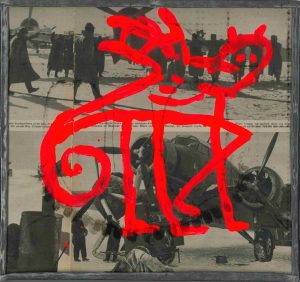

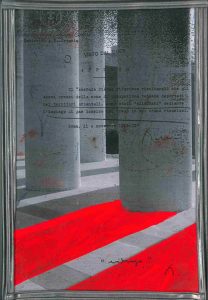

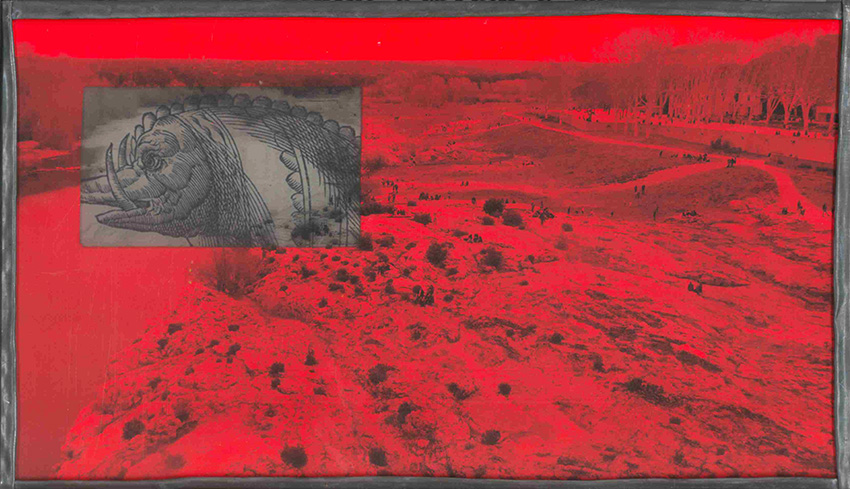

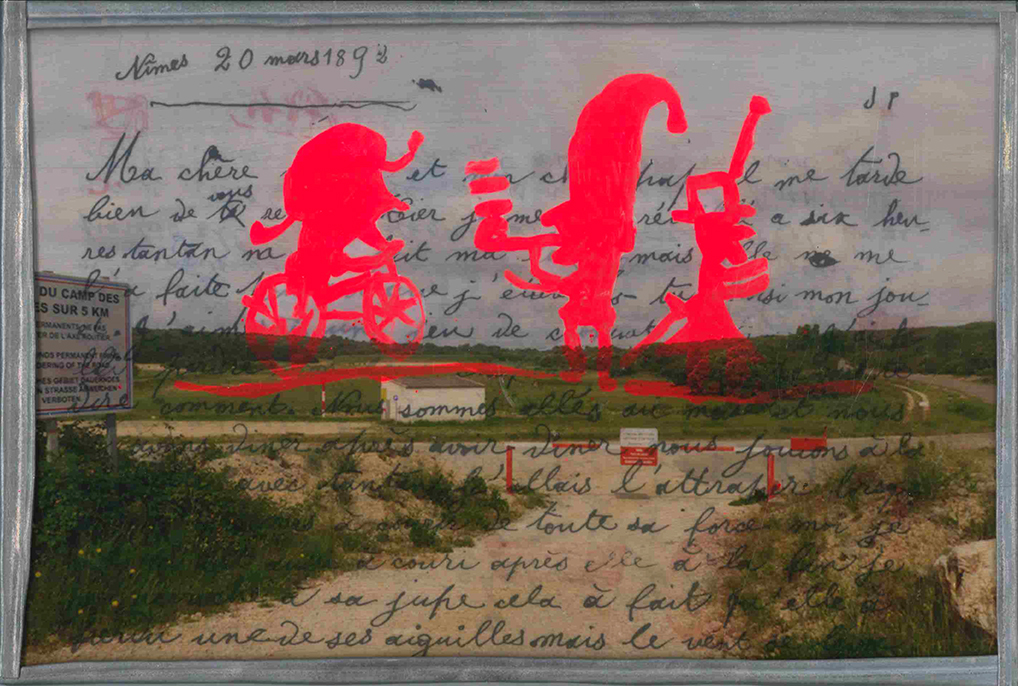

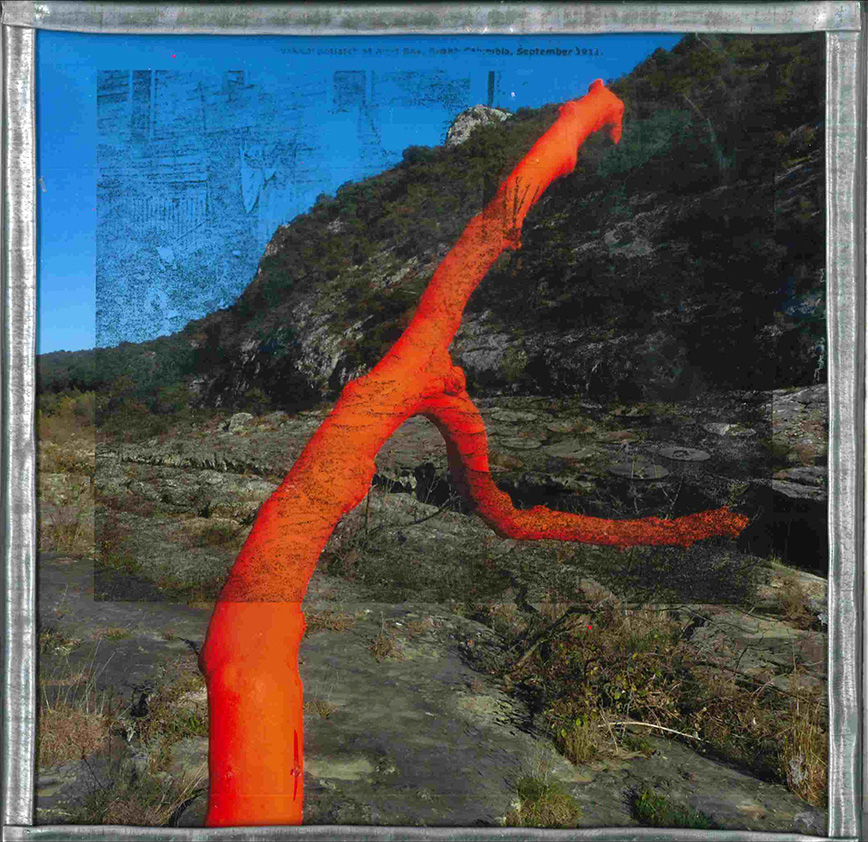

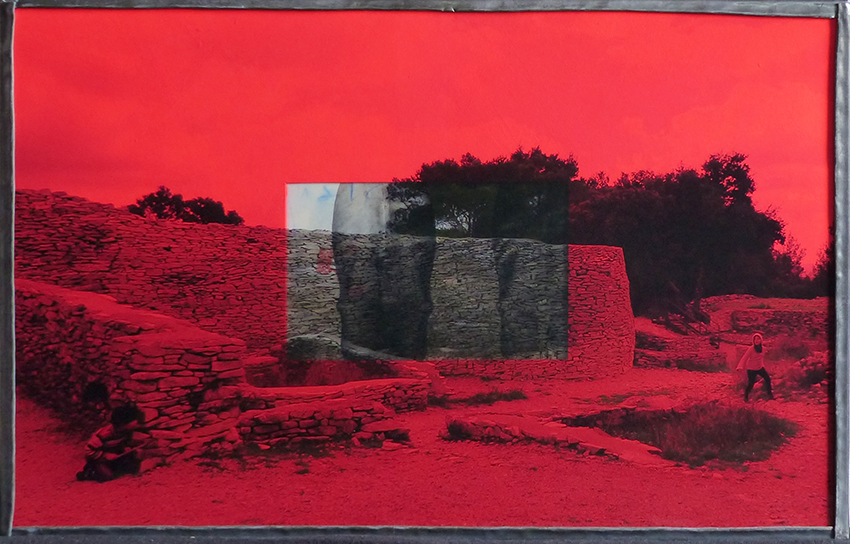

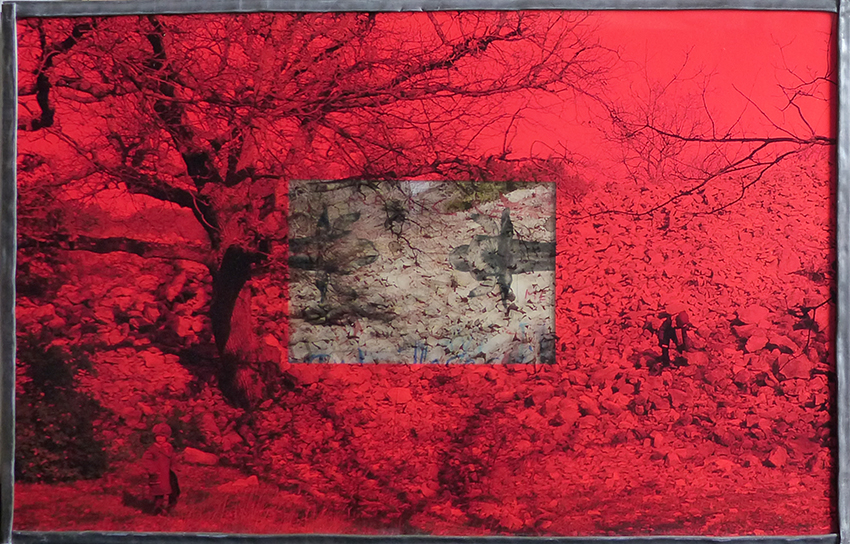

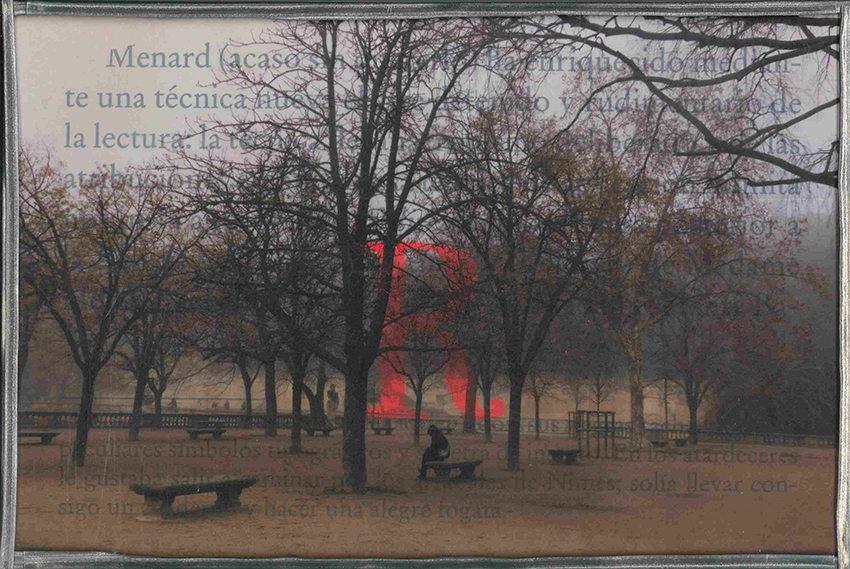

Circa dodici anni dopo la realizzazione della mia installazione del 2006, Ex voto, di cui ho parlato prima, e trenta anni dopo la mia scoperta della Postdamerplatz e l’inizio del mio lavoro su immagini trovate, ho presentato una nuova installazione basata sulla fotografia. Questa volta il progetto era più centrato sulla ‘’grande’’ Storia, in un intreccio con la mia storia personale. In questo senso, “storicizzo” me stesso come uomo che ha vissuto la maggior parte della sua vita nel secolo scorso; è per questo che ho intitolato questo lavoro Millenovecento.

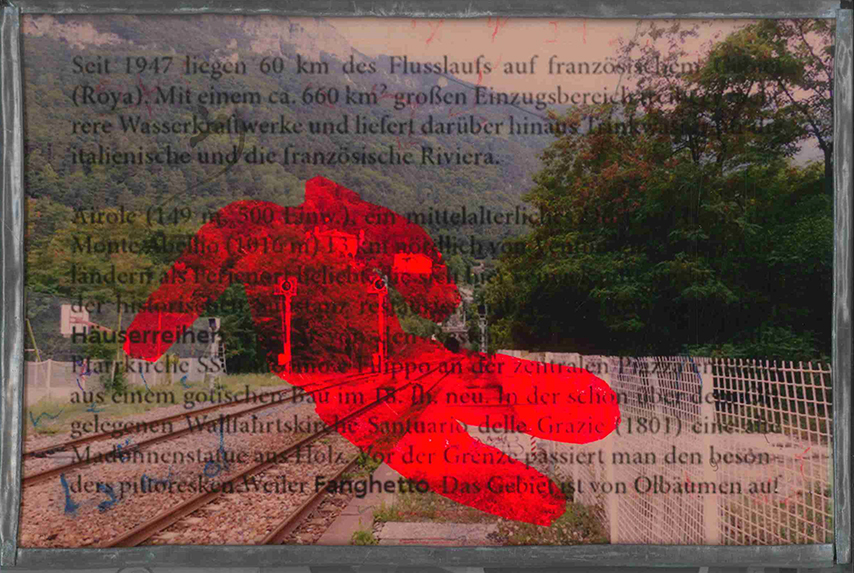

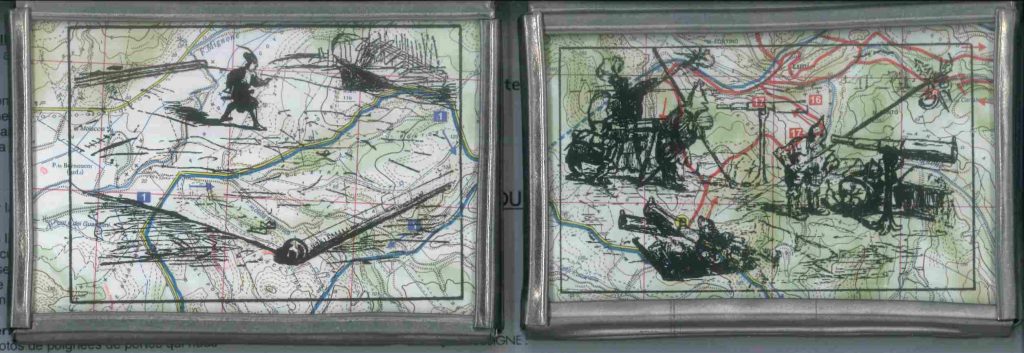

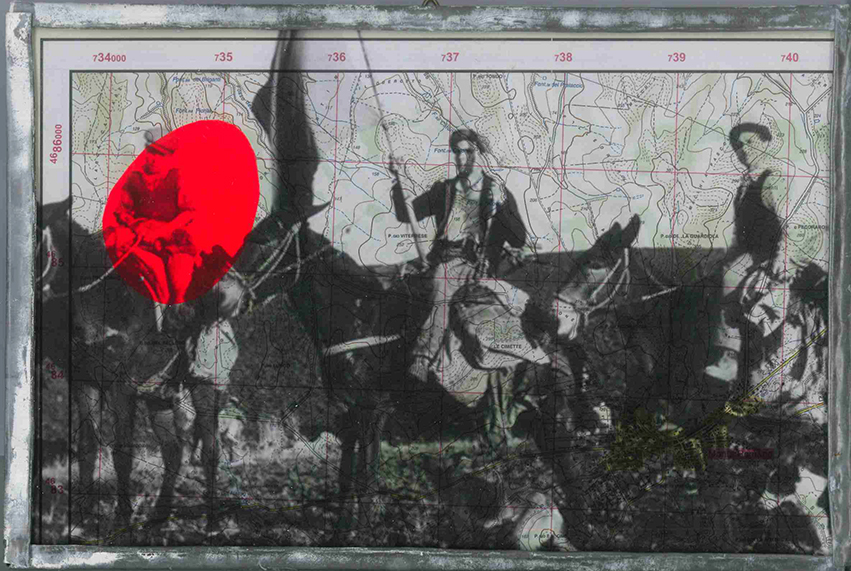

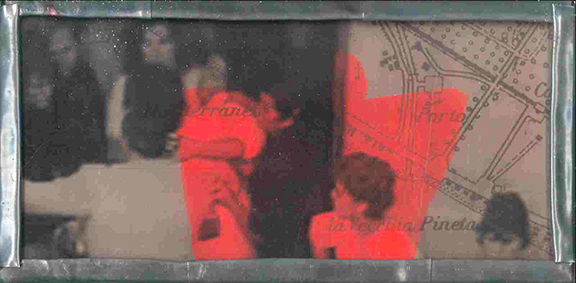

In genere non rispetto una gerarchia delle immagini, che sia per la qualità o per l’importanza del soggetto. Perciò ho mescolato stampe analogiche delle mie foto con ritagli di giornale, fotocopie e fotografie da archivi privati. A volte ho riprodotto su vetro l’immagine e l’ho sovrapposta a testi su carta, altre volte è la foto su carta che fa da fondo a un testo o a un’incisione riprodotti su vetro. Ogni volta c’è un passaggio di colore, un rosso luminescente, che crea uno sbalzo nella visione e che è, sino ad oggi, la mia firma.

A proposito di questo metodo di rievocazione e di trasformazione: oggi sarebbe considerato aberrante ciò che facevano gli archeologi del re di Napoli quando Pompei fu riscoperta nel XVIII secolo, o ciò che fanno i tombaroli nelle sepolture etrusche, quando entrano dall’alto e penetrano da una stanza all’altra sfondando le pareti solo per riportare alla superficie gli oggetti preziosi, senza preoccuparsi, appunto, del loro contesto.

A proposito di questo metodo di rievocazione e di trasformazione: oggi sarebbe considerato aberrante ciò che facevano gli archeologi del re di Napoli quando Pompei fu riscoperta nel XVIII secolo, o ciò che fanno i tombaroli nelle sepolture etrusche, quando entrano dall’alto e penetrano da una stanza all’altra sfondando le pareti solo per riportare alla superficie gli oggetti preziosi, senza preoccuparsi, appunto, del loro contesto.

Dalla seconda metà del XIX secolo l’archeologia, anche l’archeologia “preventiva” che richiude tutto dopo avere fatto gli scavi, lavora rimuovendo strato dopo strato. Questo metodo è proprio il contrario di una penetrazione nella materia alla ricerca della perla rara o del corallo prezioso, senza considerazione per l’ambiente cui appartiene.

(2019-2021, Millenovecento, installazione e dettagli)

(2019-2021, Millenovecento, installazione e dettagli)

.

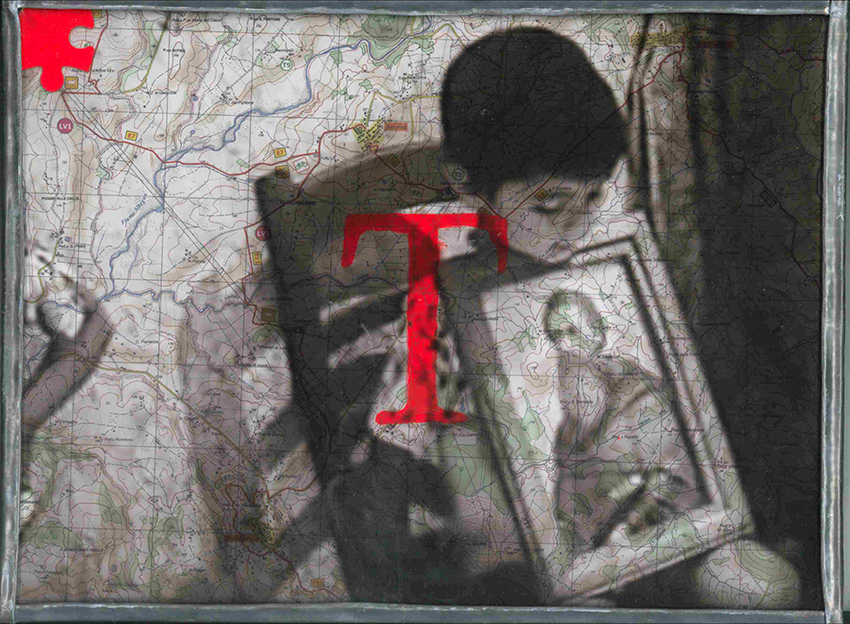

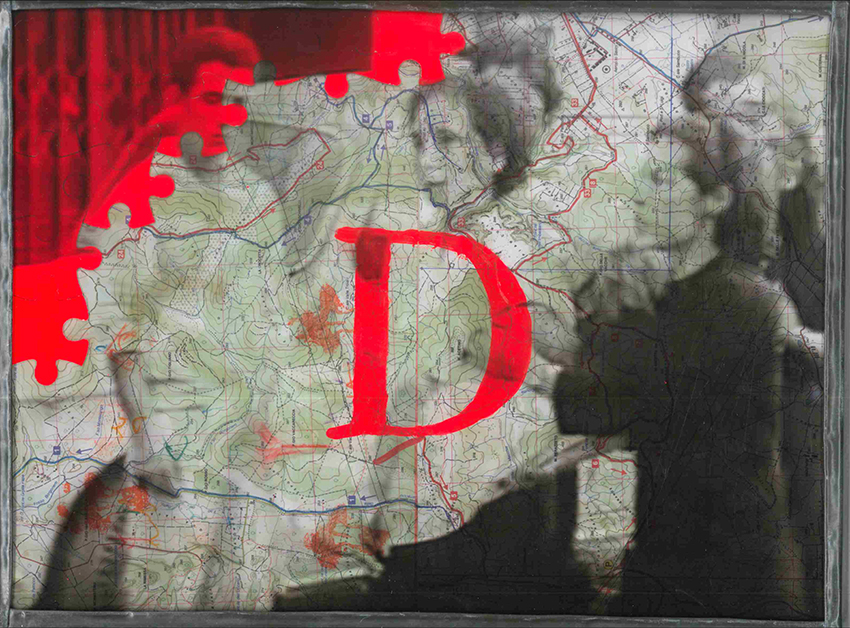

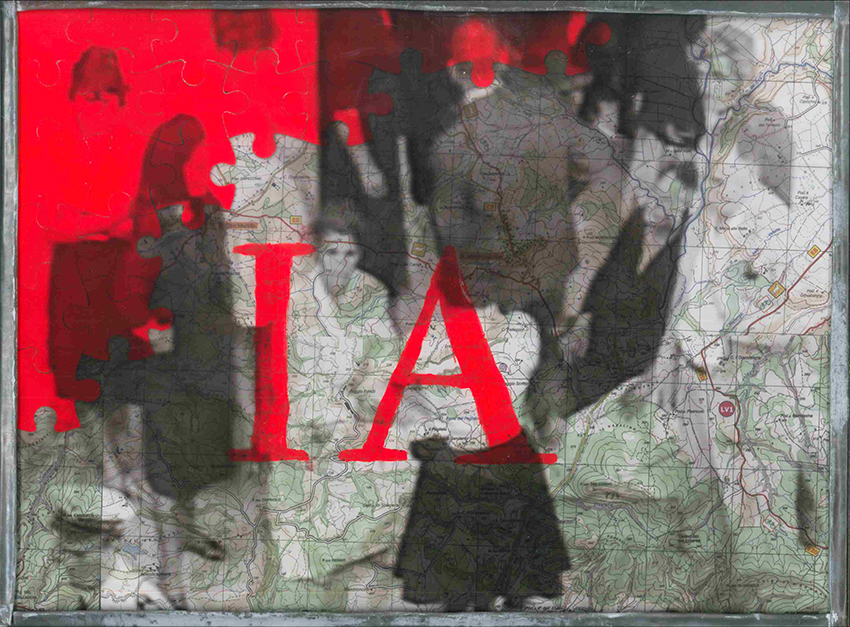

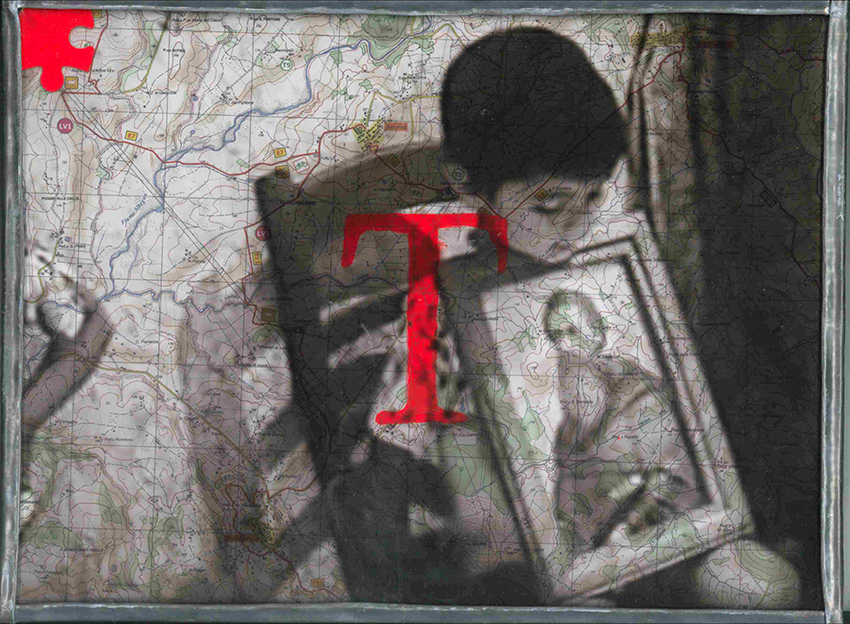

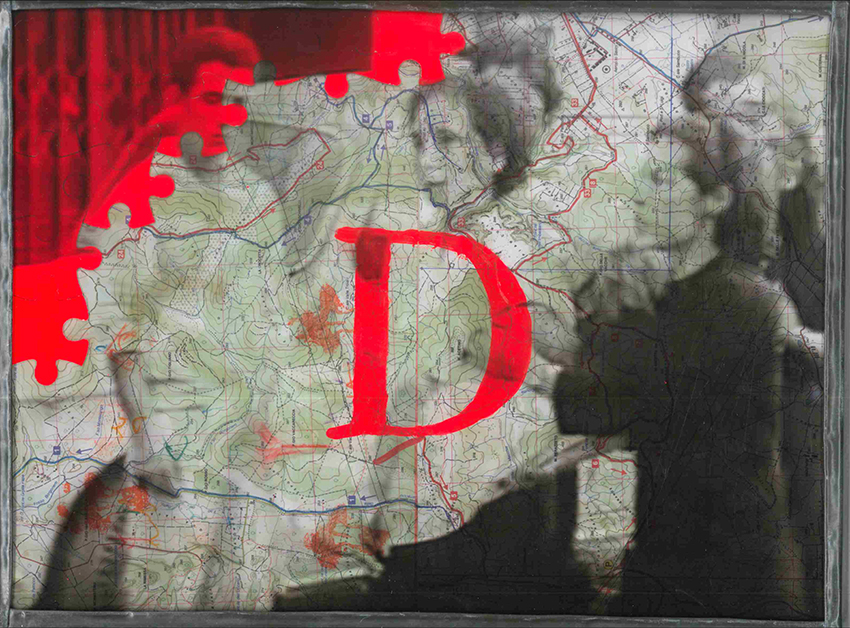

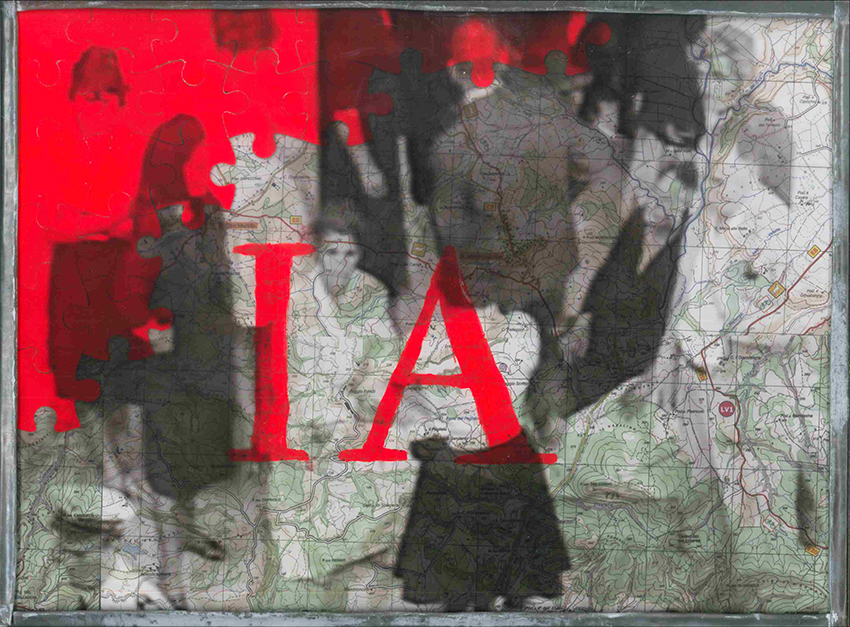

Se mi sono interessato al tema della Taranta – che in Italia è lontano dall’essere solo un soggetto di studi etno-demo-musicologici – ma è diventato un fenomeno di cultura popolare, allo stesso tempo colto e di massa – è perché, viste la mia età e le mie origini geografiche, avrei potuto essere io stesso uno di quei ragazzi che guardano la tarantolata dalla finestra della casupola in cui sono accorsi i tre musicisti-terapeuti.

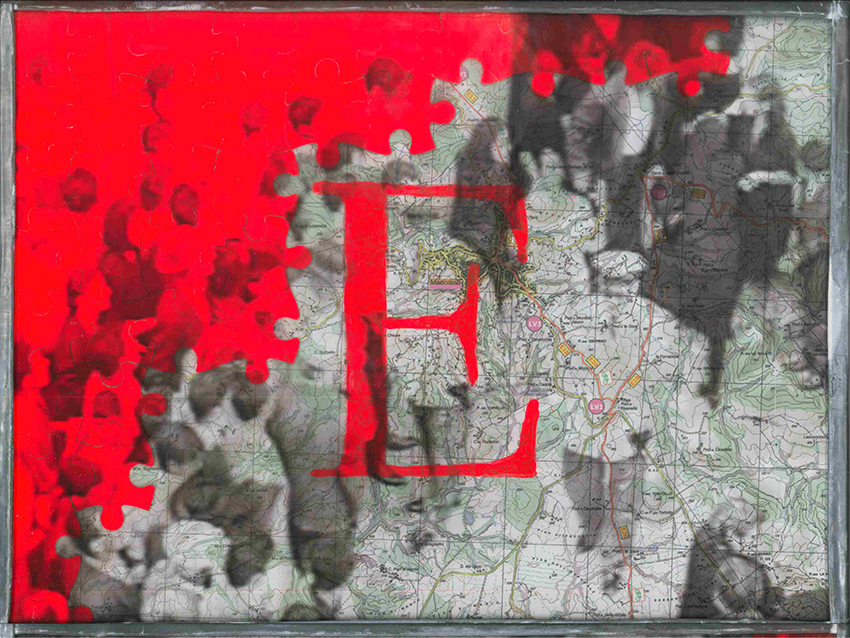

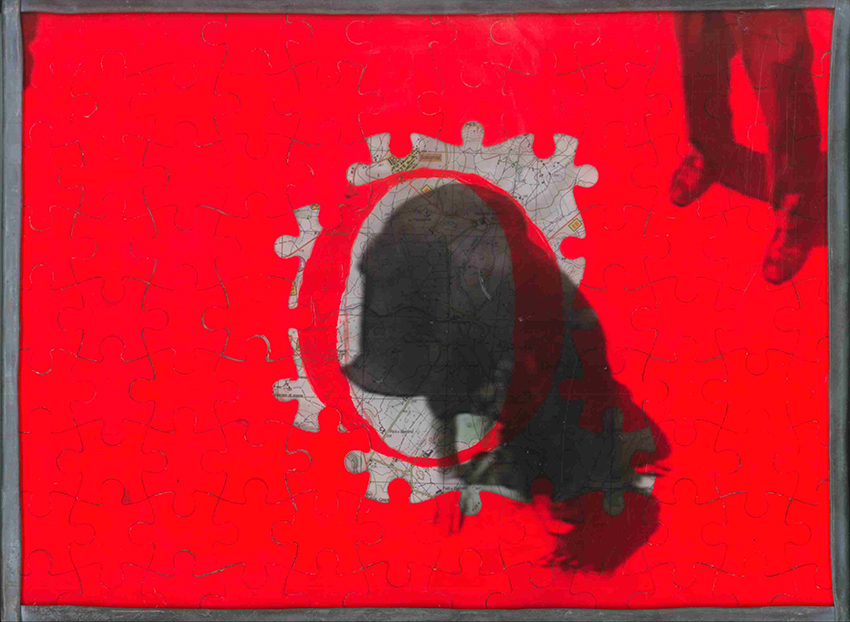

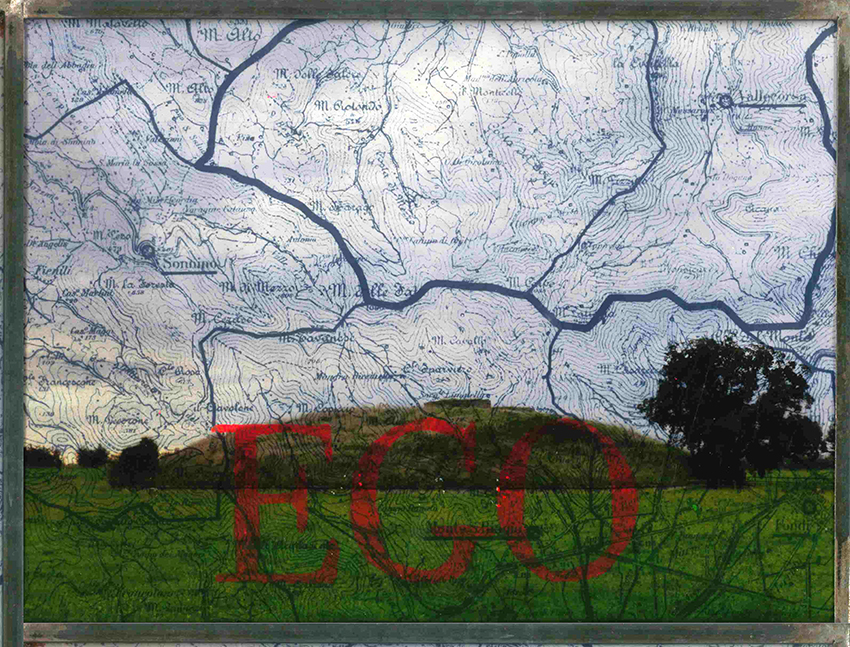

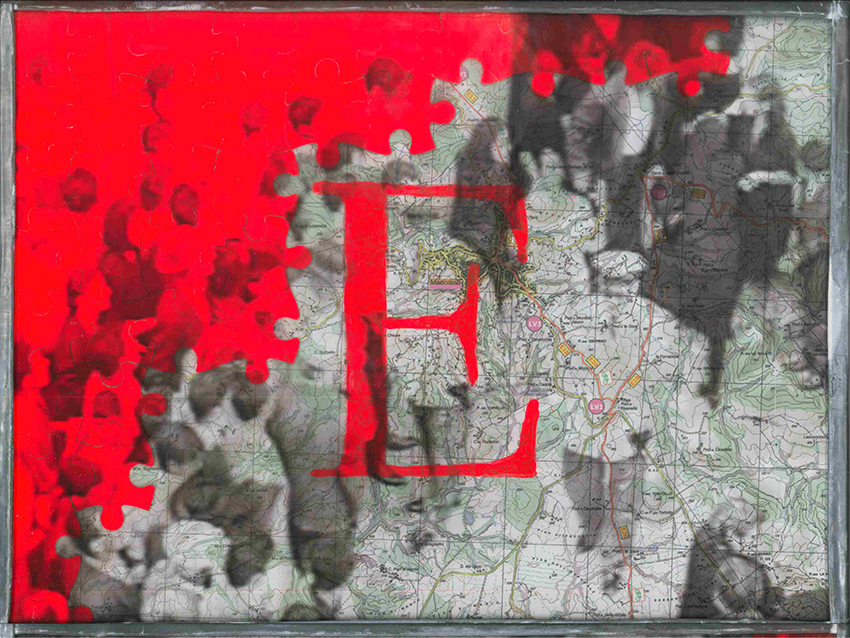

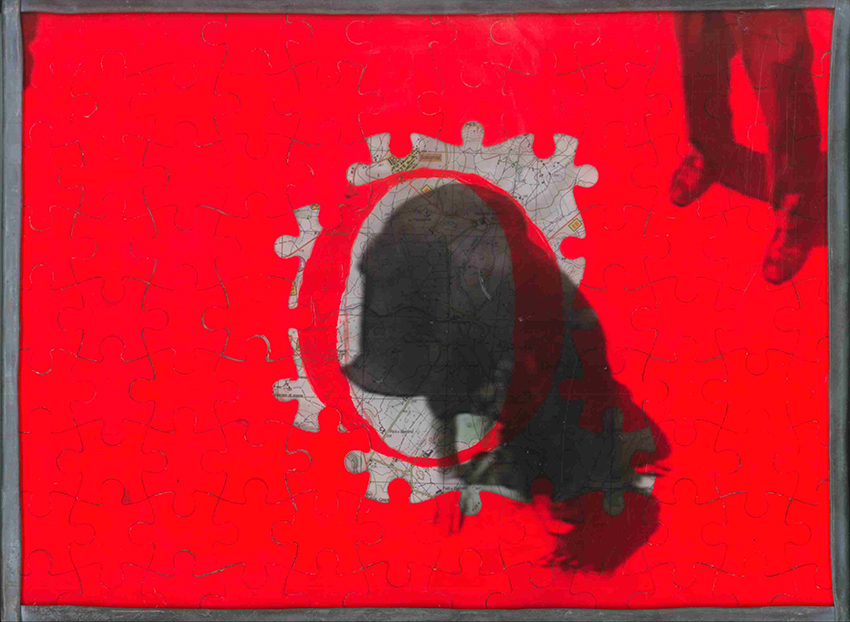

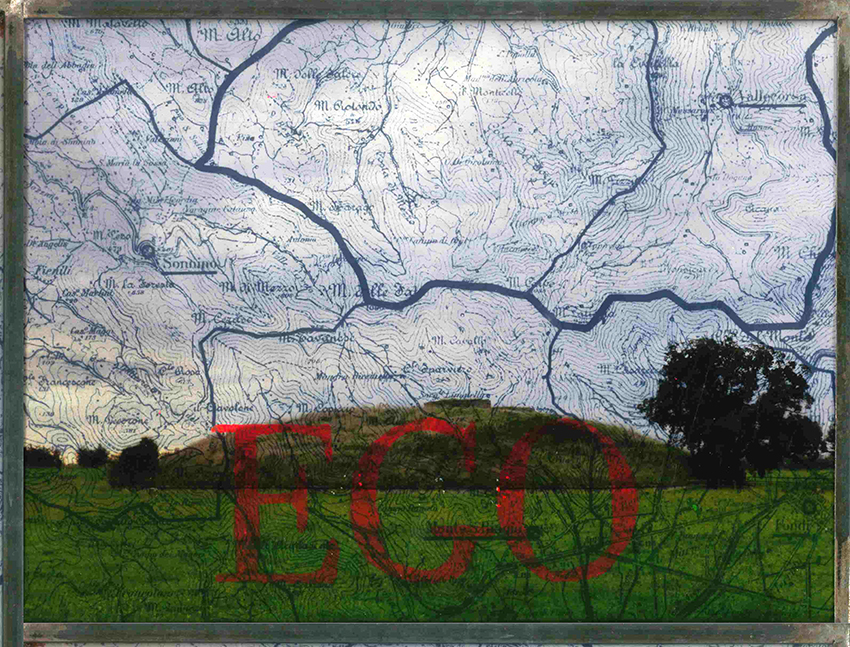

Per questa nuova serie ho ripreso una serie precedente di nove piccoli formati (Galatina 1961), scegliendo diversi fermi-immagine, di interesse più “autobiografico”, a partire dal documentario di Gianfranco Mingozzi La Taranta (1962). La serie Galatina Remix comprende quindi dodici pezzi formato 30x40cm, ognuno dei quali riporta una o due lettere della frase Et in Arcadia Ego, trascritta su una carta topografica del Meridione d’Italia. Ogni quadro è completato da tasselli di puzzle dipinti in rosso fluorescente e disposti secondo la sequenza di Fibonacci, da 0 per il primo a 89 per il dodicesimo (come sappiamo, la progressione di Fibonacci, nata per calcolare il tasso di riproduzione dei conigli, considera ogni numero come l’addizione dei due che lo precedono).

Nell’ultimo quadro della serie il puzzle è quasi completo e l’immagine (la donna vestita di nero che ruota intorno alla piazza fino a crollare sul cuscino che il marito ha portato e le pone sotto il capo) è quasi completamente coperta di rosso. Come dice Quasimodo a conclusione del suo testo di accompagnamento al documentario:

Quello che poteva sembrare oleografia o folklore entra ora nel campo della cura neurologica. Nell’evoluzione del mondo di oggi, quest’antica eredità del medioevo consuma ormai il suo ultimo tempo.

Confesso che ho scelto questa formula pensando a Mario Merz (Crocodilus Fibonacci, 1972, tra l’altro) e alle forme a spirale che ho impiegato in lavori recenti (Going round and round, 2024).

(2022, Galatina remix)

(2022, Galatina remix)

.

.

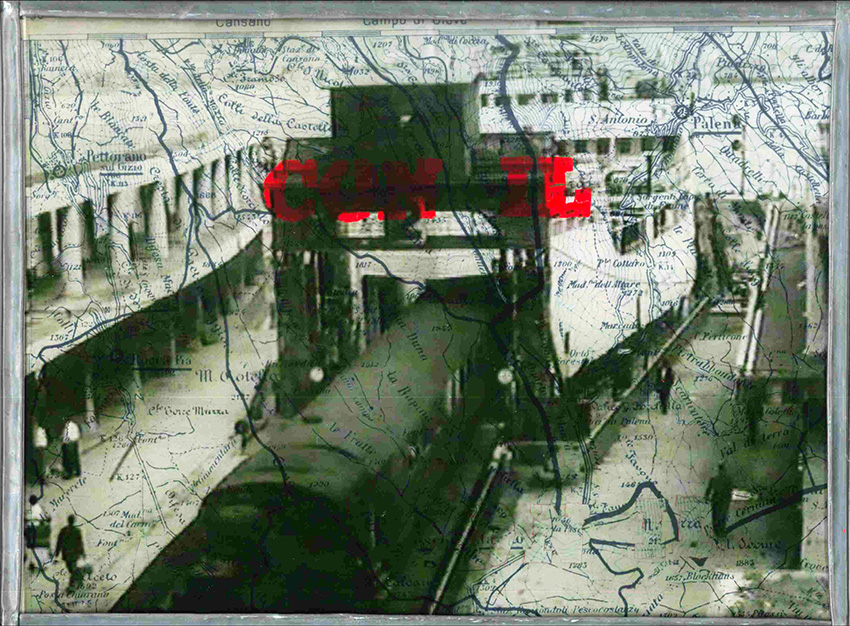

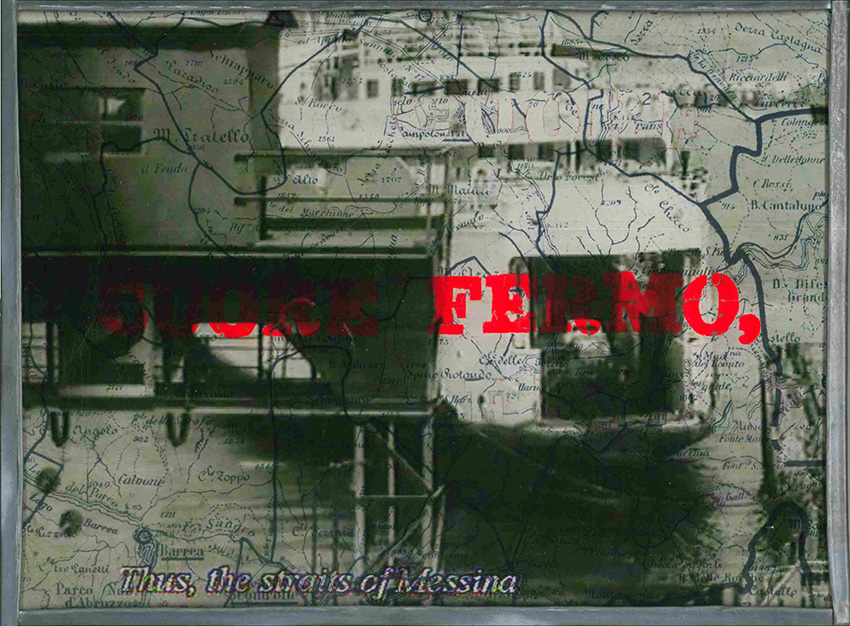

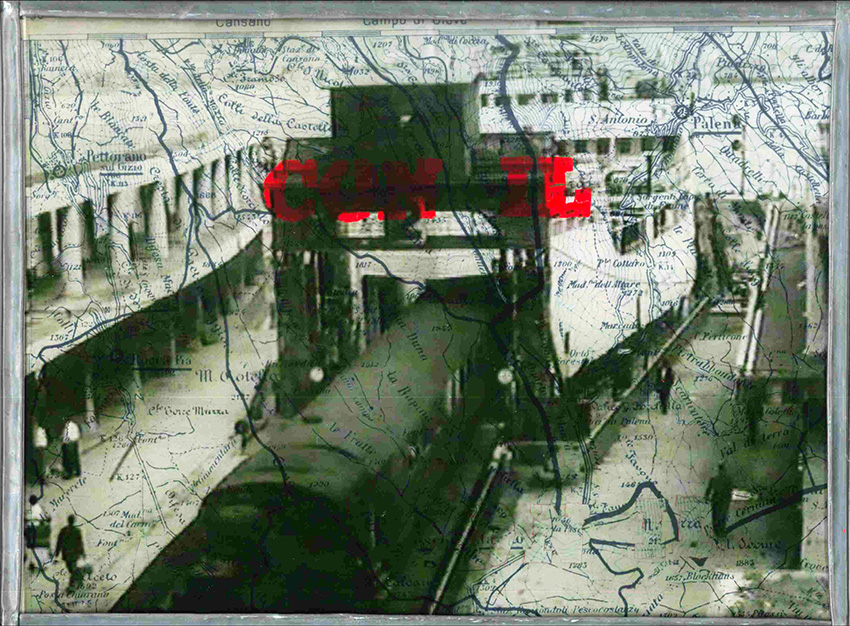

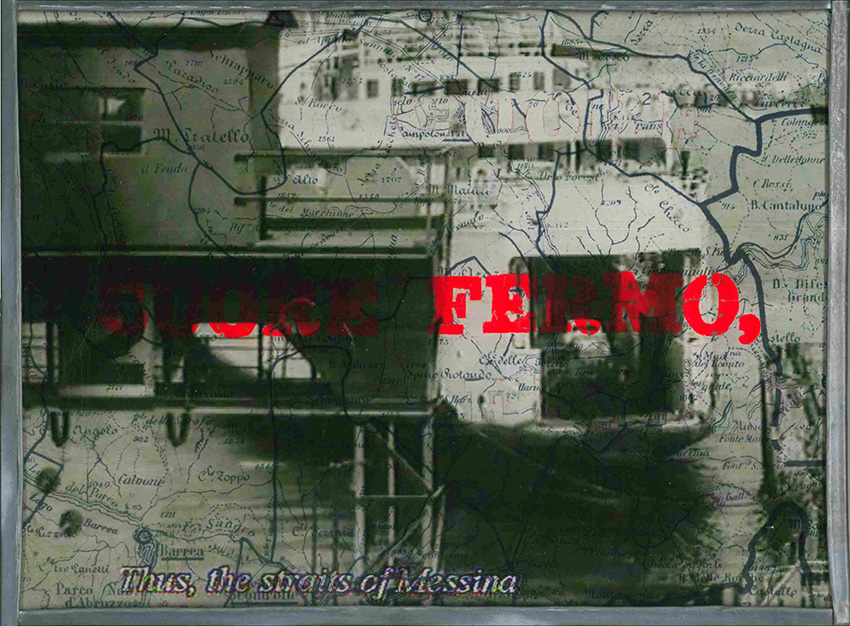

(2022, Con il cuore fermo)

(2022, Con il cuore fermo)

.

Vorrei ora mostrare brevemente un altro lavoro tratto da un film documentario di Gianfranco Mingozzi: Con il cuore fermo. Sicilia, del 1965. Il tema è l’emigrazione cui sono costretti i giovani siciliani, oppressi da un sistema agricolo feudale e, certo, dal potere della mafia.

Di questo film ho utilizzato solo alcuni fotogrammi tratti dalla prima sequenza, in cui una voce fuori campo elenca le statistiche sull’emigrazione dalla Sicilia verso l’Europa settentrionale e in cui si ritraggono i familiari che si accomiatano sul molo della stazione marittima di Messina.

Ho inciso il titolo, rispettando il carattere e il formato originali, con una penna Bic su carte topografiche. Attraverso le parole del titolo, lo sfondo del quadro, in rosso fluorescente. I tre fermi immagine sono trasferiti su vetro e costituiscono il primo piano di ogni pezzo.

.

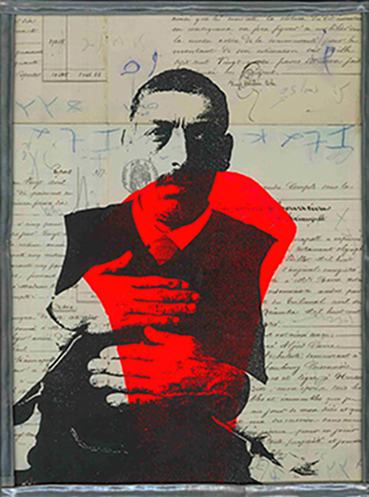

Sei. Fenomeni morbosi.

Non so se Antonio Gramsci è mai stato ad Urbino, ma mi sono premurato di portarcelo io, in effigie, quattro secoli dopo il soggiorno di Paolo Uccello. Questo è il potere dell’artista, che non viene concesso allo storico né allo storico dell’arte.

Non so se Antonio Gramsci è mai stato ad Urbino, ma mi sono premurato di portarcelo io, in effigie, quattro secoli dopo il soggiorno di Paolo Uccello. Questo è il potere dell’artista, che non viene concesso allo storico né allo storico dell’arte.

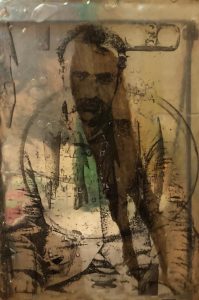

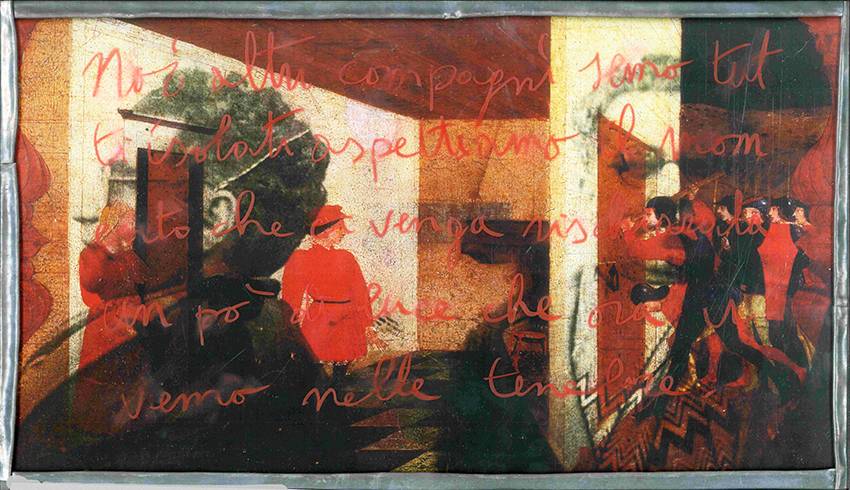

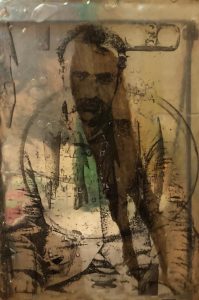

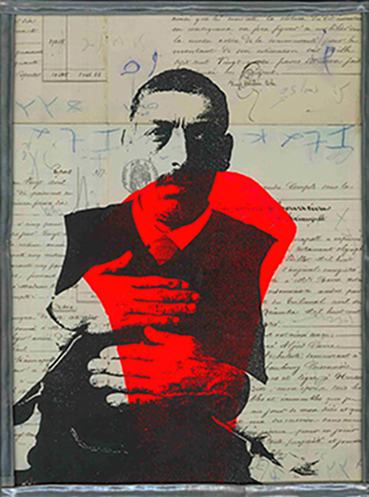

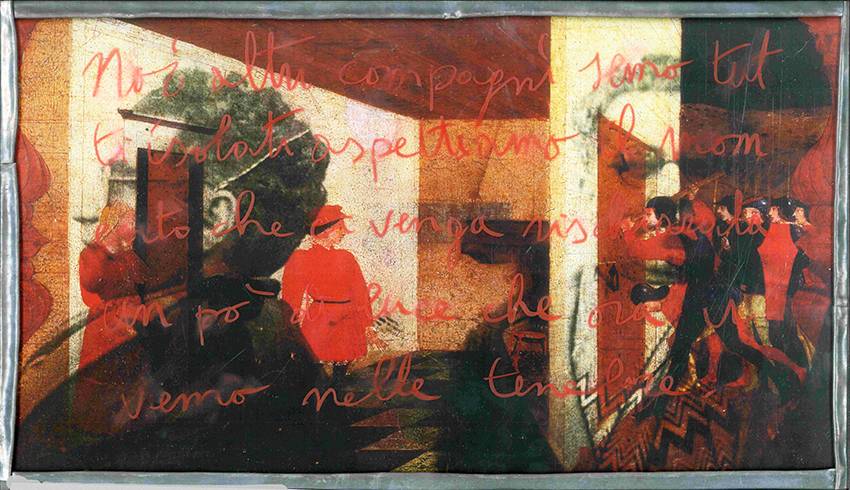

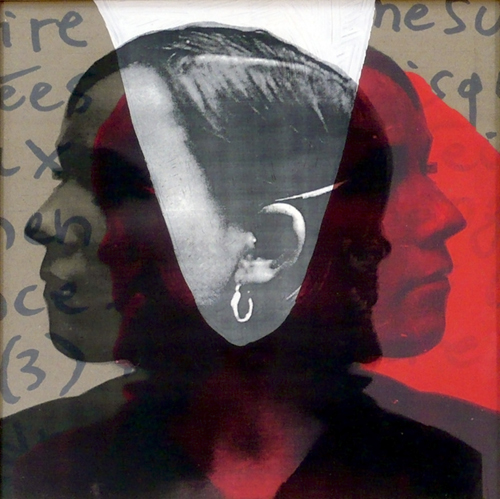

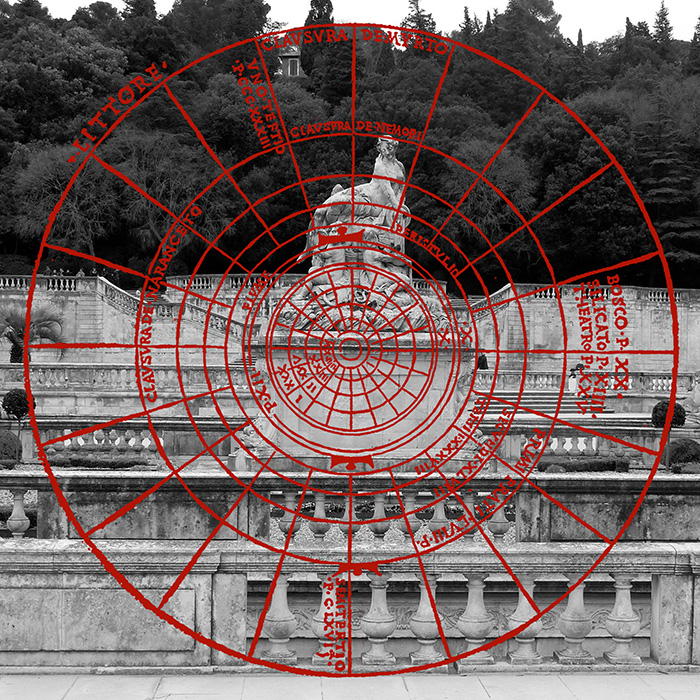

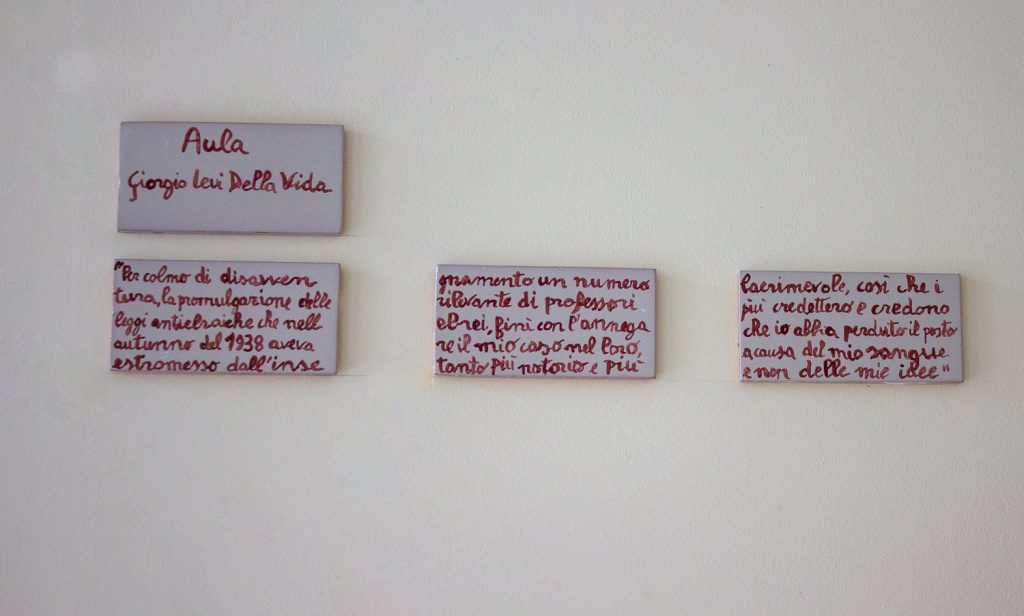

Questo lavoro è l’ultimo della serie Fenomeni morbosi svariati. La serie comporta tre riproduzioni di scene da Il miracolo dell’ostia consacrata (Galleria Nazionale delle Marche di Urbino) di Paolo Uccello, sulle sei che costituiscono la predella, trasferite su vetro; indi, come sfondo, testimonianze provenienti dagli archivi storici italiani, in particolare il Casellario Politico Centrale dell’Archivio Centrale dello Stato di Roma.

Le fonti sono queste:

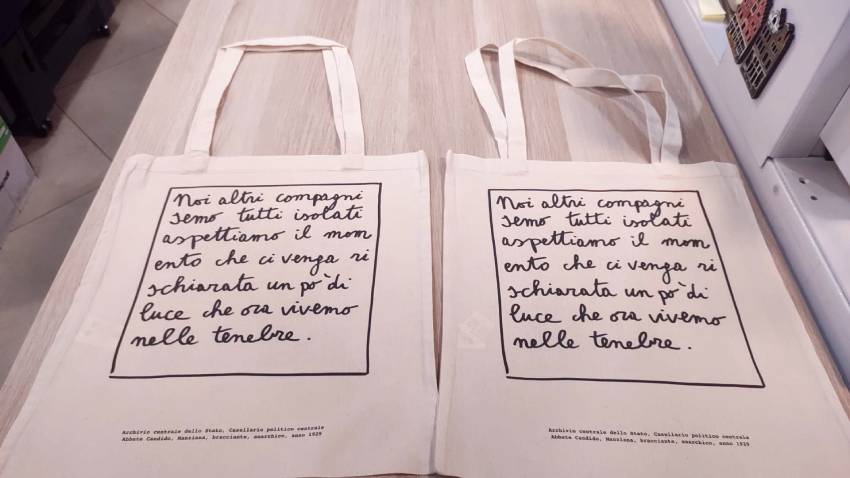

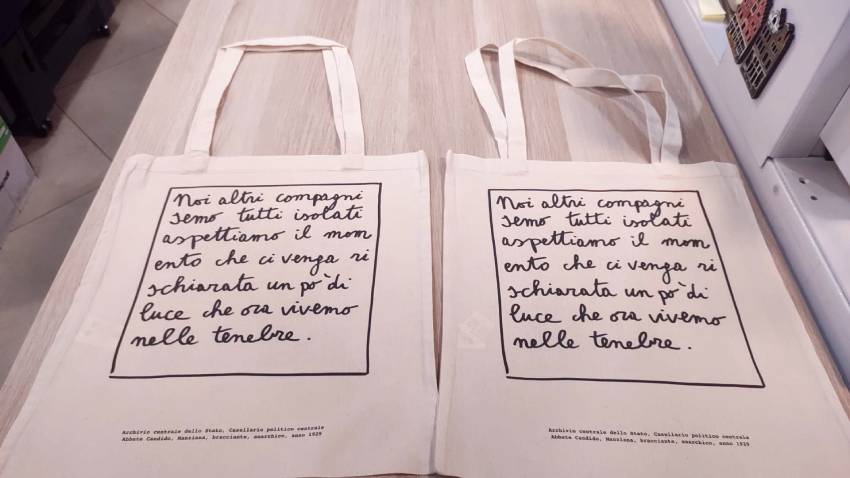

-La trascrizione manuale di una lettera sequestrata nel 1929 a un antifascista detenuto, lettera che ho trascritto nel 1979, quando ero un assiduo visitatore dell’Archivio di Stato per la mia ricerca sul movimento operaio romano: “Noialtri compagni semo tutti isolati aspettiamo il momento che ci venga rischiarata un po’ di luce che ora vivemo nelle tenebre”.

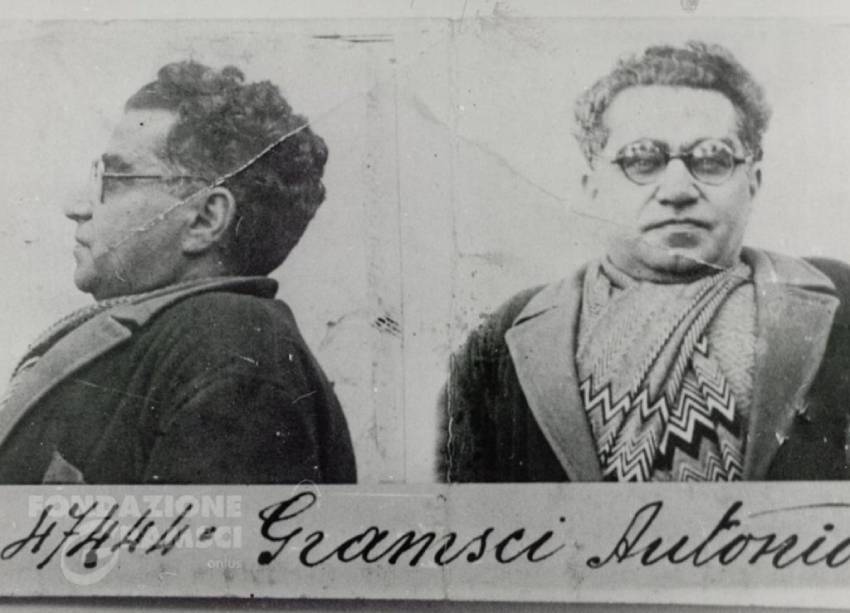

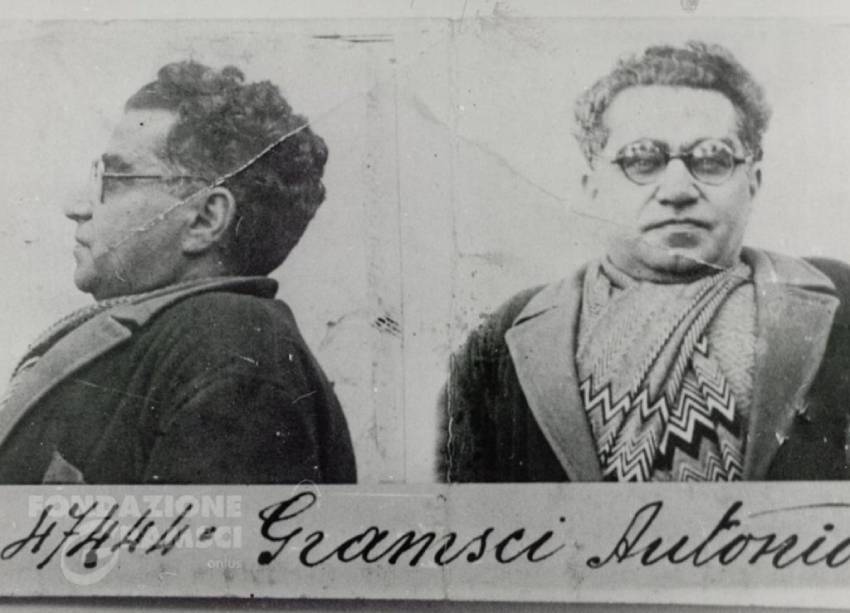

-La foto segnaletica di Antonio Gramsci del gennaio 1935, la sua ultima foto, che ho trasformato su Photoshop in un logo inspirato a quello, celebre, di Che Guevara, tratto da una fotografia di Alberto Korda.

-La prima pagina dell’indice informatico del Casellario Politico Centrale, voce ‘’detenuti politici”.

-La predella di Paolo Uccello, datata al 1467-1469 e commissionata dalla confraternita del Corpus Domini di Urbino.

In questo ultimo lavoro della serie, che ne è come una sintesi, ho riprodotto la foto segnaletica di Gramsci senza modificarla, e ho trascritto il messaggio dell’antifascista con una matita rosso fluo, rispettando gli errori grammaticali che comportava.

Nell’immaginario delle tenebre e della luce non si può non pensare alle persecuzioni religiose. Di qui la scelta della predella di Urbino. Sono anche commosso dall’espressione usata da Candido di Manziana, nonostante sia banale, “noialtri”. Curiosamente il traduttore automatico dà, in francese, “le reste d’entre nous”, “il resto di noi”. Forse, quest’erranza informatica rivela un qualcosa di giusto: “quello che rimane di noi” nei momenti oscuri. La mia traduzione invece, darebbe ‘’nous les autres’’, cioè “gli altri in noi”.

(2023, Fenomeni morbosi ter 02)

(2023, Fenomeni morbosi ter 02)

.

Sette. Rovine nella foresta.

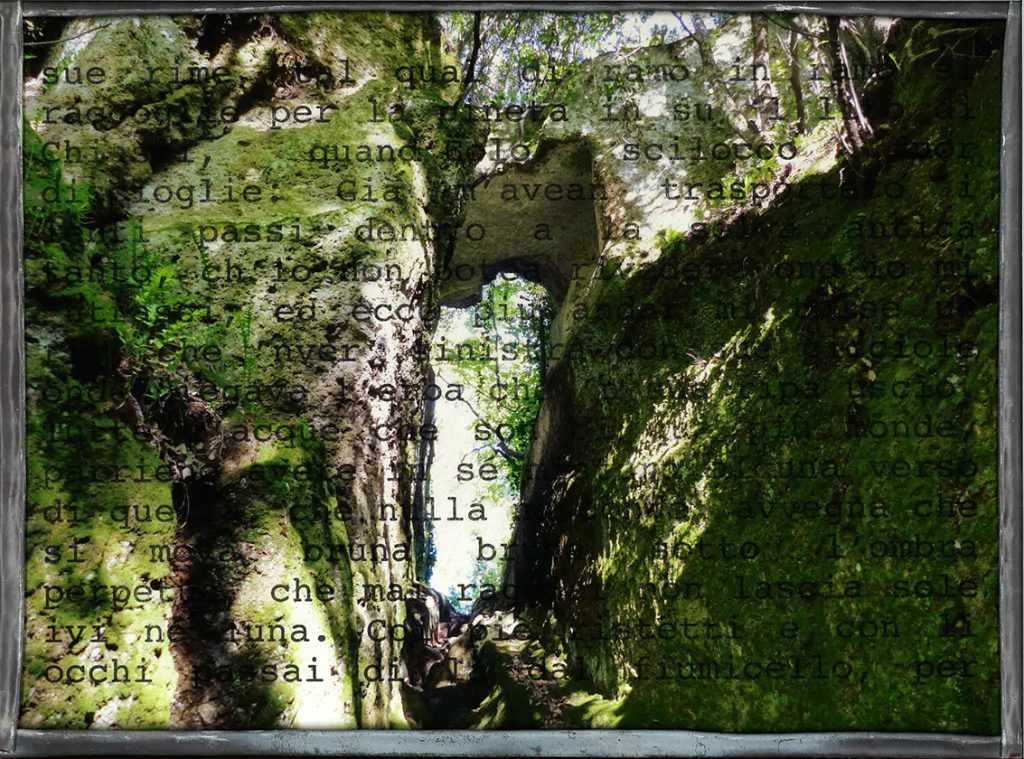

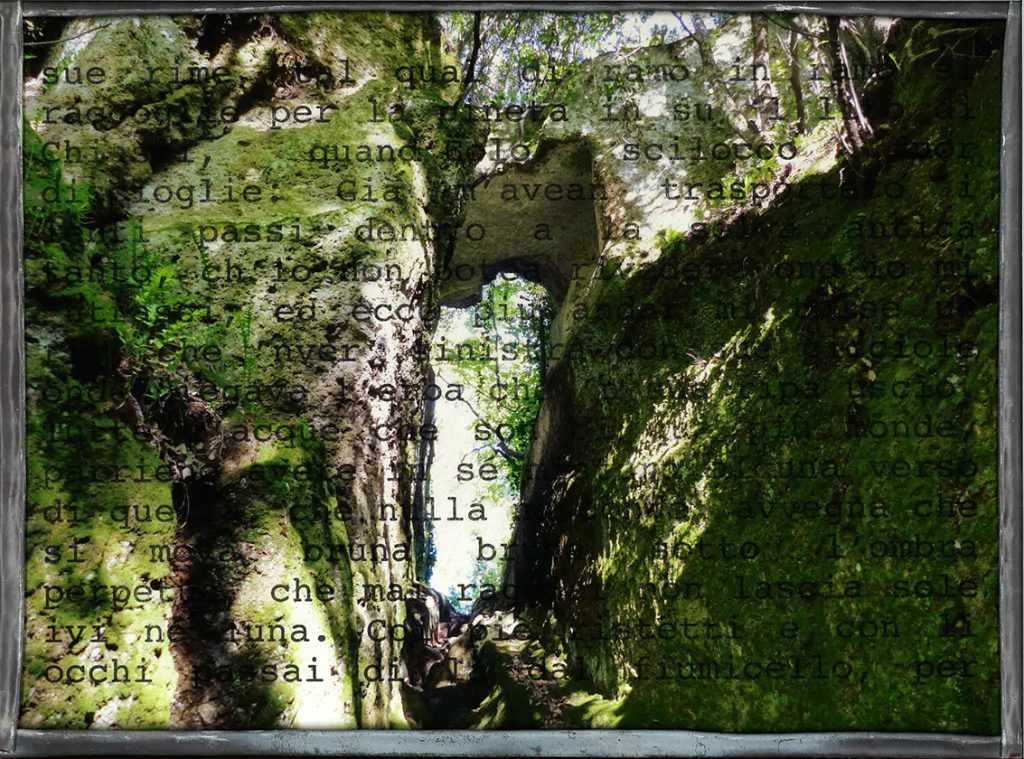

Già m’avean trasportato i lenti passi dentro a la selva antica tanto, ch’io non poteva rivedere ond’io mi `ntrassi…

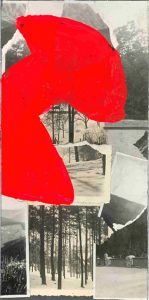

(2023, Rovine nella foresta 01-04)

(2023, Rovine nella foresta 01-04)

.

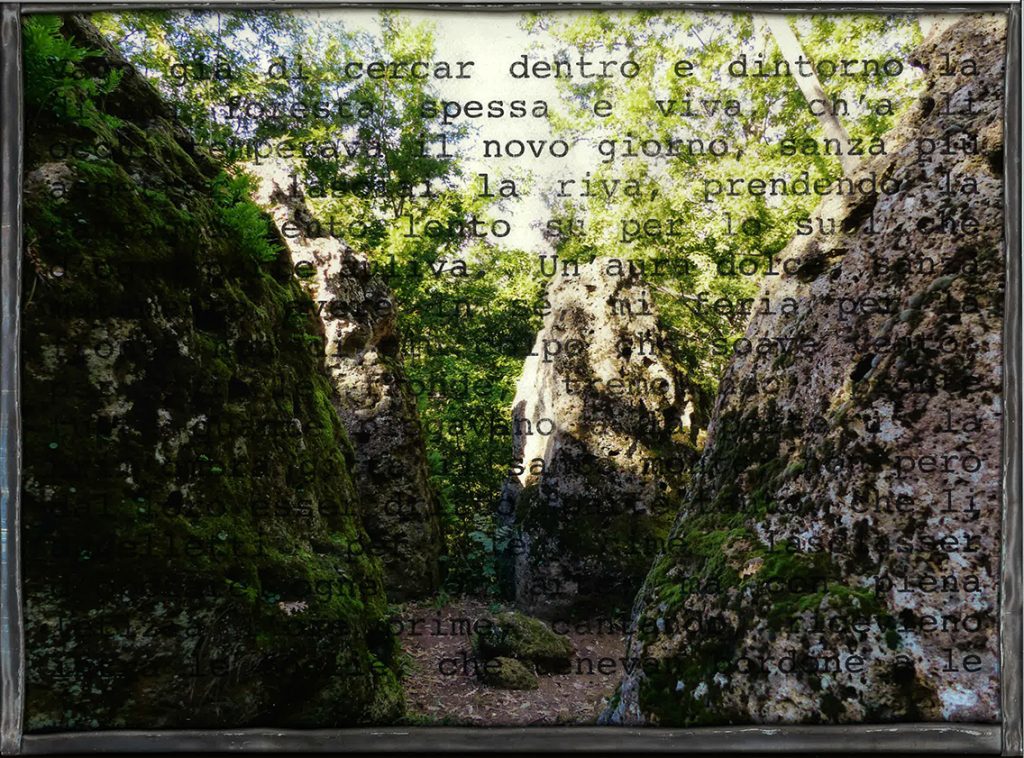

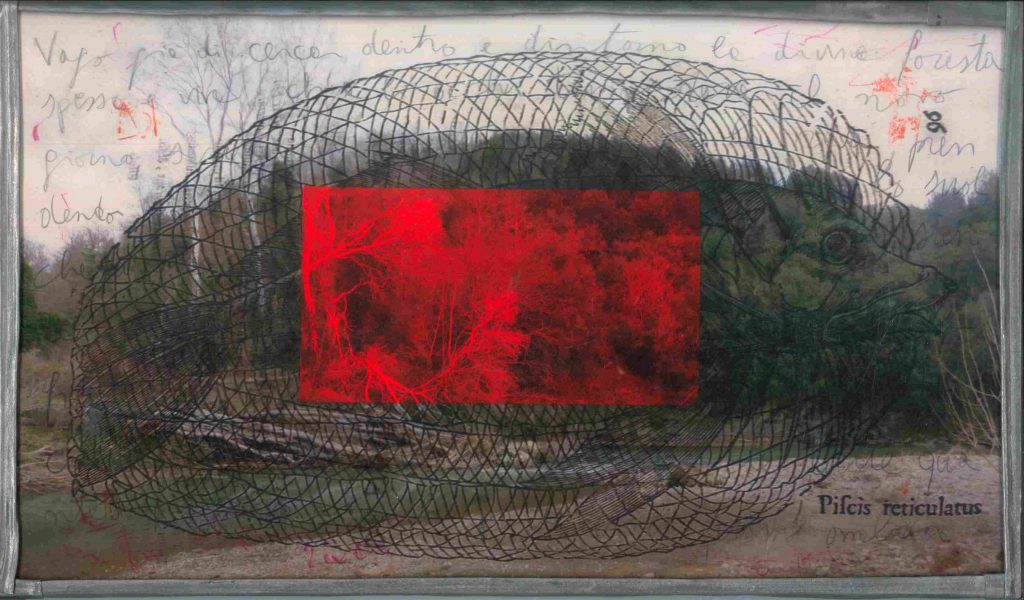

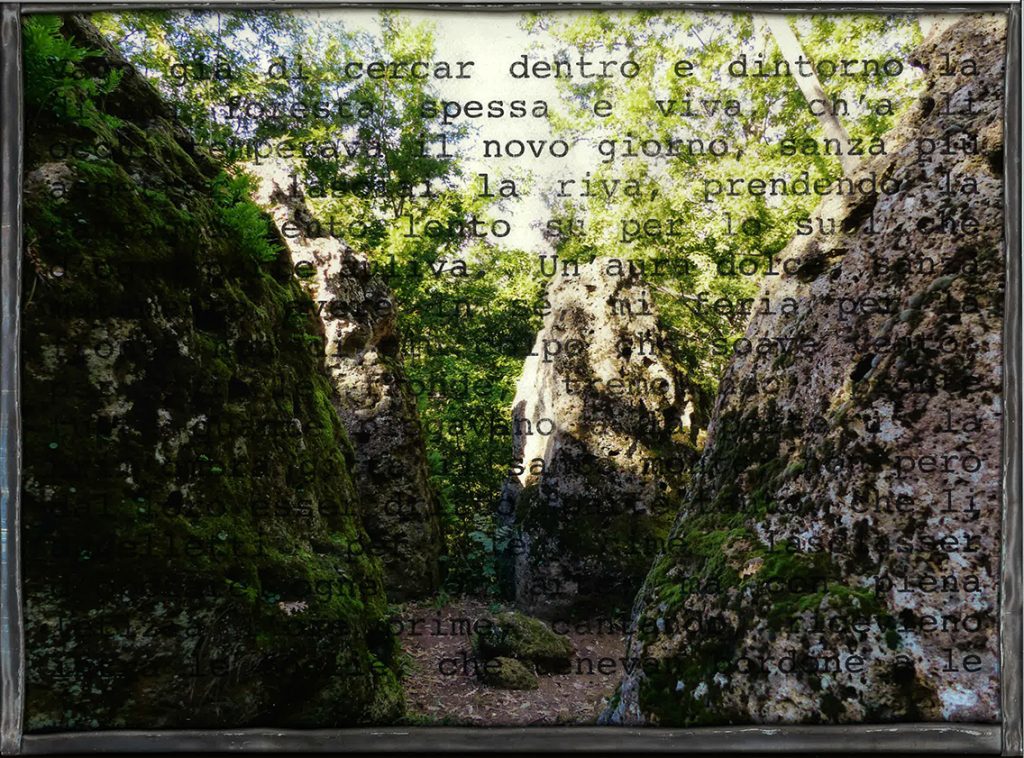

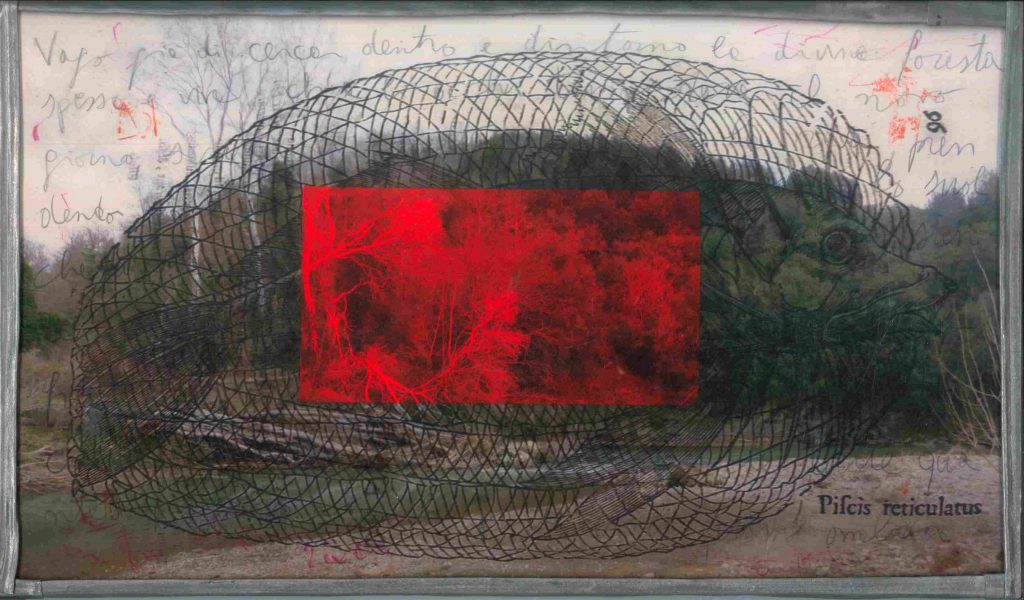

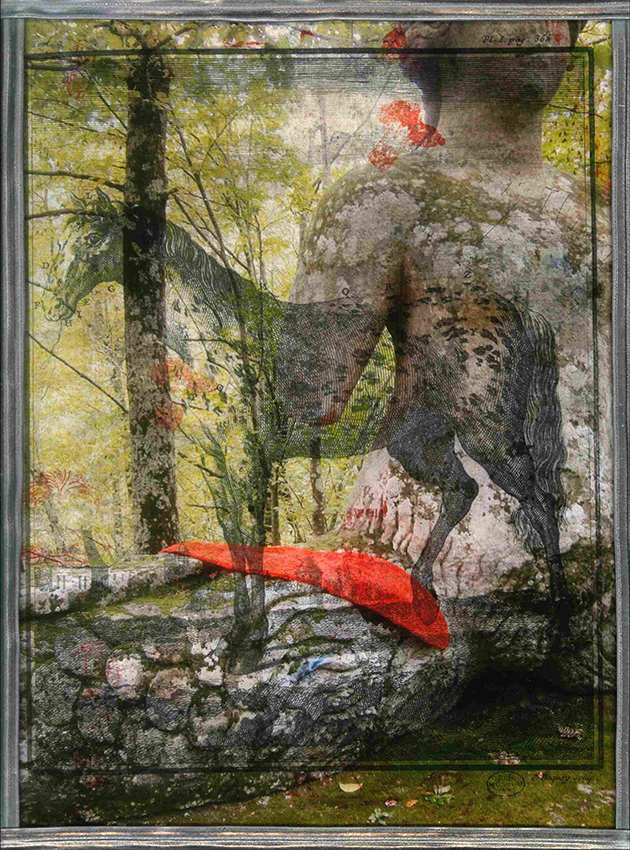

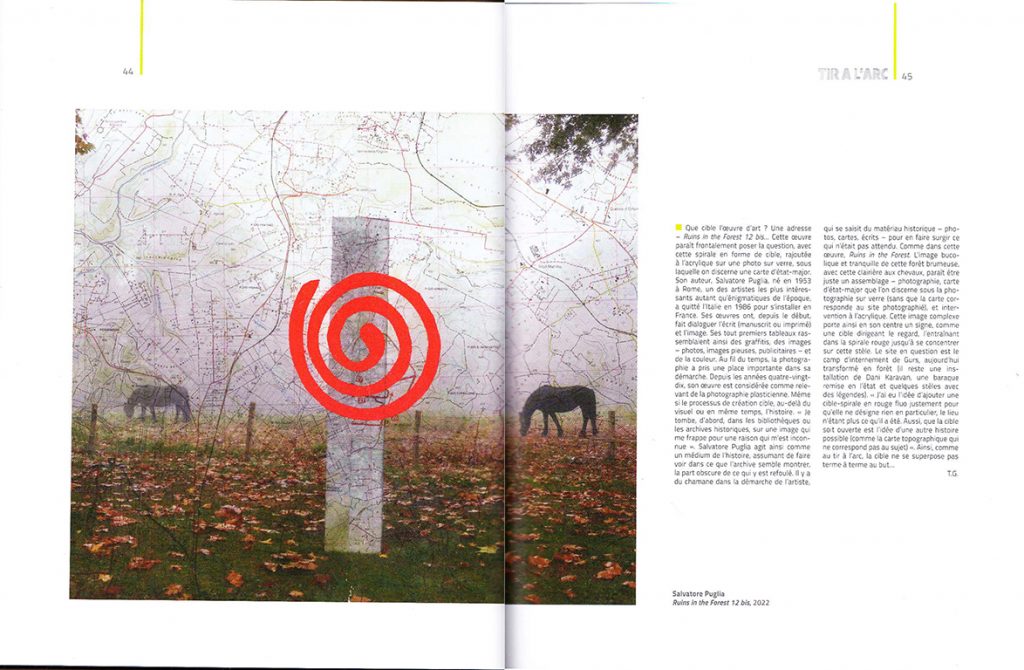

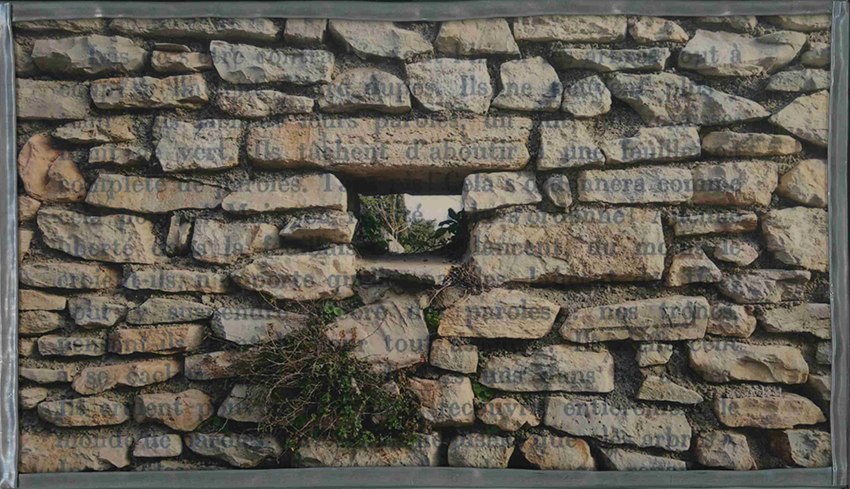

Da ormai qualche anno lavoro sul tema della natura soggetta alla civiltà (e vice versa), ben sapendo che, dopo la lettura del Par-delà nature et culture (Paris 2005) di Philippe Descola, non esiste più uno spazio naturale libero dall’intervento dell’umano. Nelle fotografie che faccio in giro per l’Europa c’è sempre un elemento naturale che predomina sulla presenza delle impronte umane, ridotte a tracce e segni minimi seppur presenti. È il concetto di “rupestre” che mi interessa.

Se il termine “rupestre” definisce forme d’arte fatta su o con le rocce (le tombe, i santuari, i graffiti, le pitture), può anche essere impiegato per descrivere i manufatti inselvatichiti, quando divengono parte della natura circostante.

Nel seguire questa traccia sono tornato a Dante, in particolare ai versi della Commedia nei quali il poeta parla di un’antica foresta che non è altro che la rappresentazione di un mondo privo di umani. I versi del Canto XXVIII del Purgatorio descrivono una “selva antica” che non è altro se non il paradiso terrestre, ove una volta l’uomo ha vissuto in stato di grazia, lontano dal peccato e dalla tecnologia. Ho lavorato in modo allegorico su questo soggetto di un Eden perduto e non ancora ritrovato; ne ho fatto due serie di quadri, una serie A e una serie B, idealmente poste l’una di fronte all’altra.

La prima serie è composta da dieci stampe su vetro, nel formato 30×40. Attraverso l’immagine resa trasparente, si può leggere il testo di Dante, riprodotto su una carta Canson senza soluzione di continuità, come un telegramma.

Dante Alighieri è stato probabilmente l’ultimo visitatore di un giardino dell’Eden. Nessuna foresta, neanche la selva concresciuta fra le formazioni vulcaniche del Lamone può essere oggi chiamata “primordiale”. Anche la conservazione della natura è un fatto artificiale. Nella riserva naturale le tracce della “civiltà” sono visibili ovunque: mura di recinzione crollate, resti di pavimentazione romana, solchi scavati dai carri dei carbonai, cumuli di pietre che furono torri etrusche e, infine, le strisce rosse e bianche della segnaletica escursionistica.

Questa non è certo la natura descritta da Leopardi, la crudele deità che nelle sue manifestazioni distruttive non si preoccupa certo del destino umano (Dialogo della natura e di un islandese, 1824). Questa è una “riserva”, un posto in cui il “primigenio” è solo reminiscenza.

Elementi naturali e umani sono qui indistinguibili, fusi in un mondo in cui non si sa più chi è che primeggia. Non si sa se lì un pescatore venuto da un’altra galassia potrebbe trovare le ossa che sono diventati coralli, gli occhi che sono diventati perle, nemmeno praticando la teoria anti-scientifica proposta da Hannah Arendt : la perforazione contro la stratigrafia, cioè la necessità di distruggere il passato per estrarne ciò che è “prezioso e raro”.

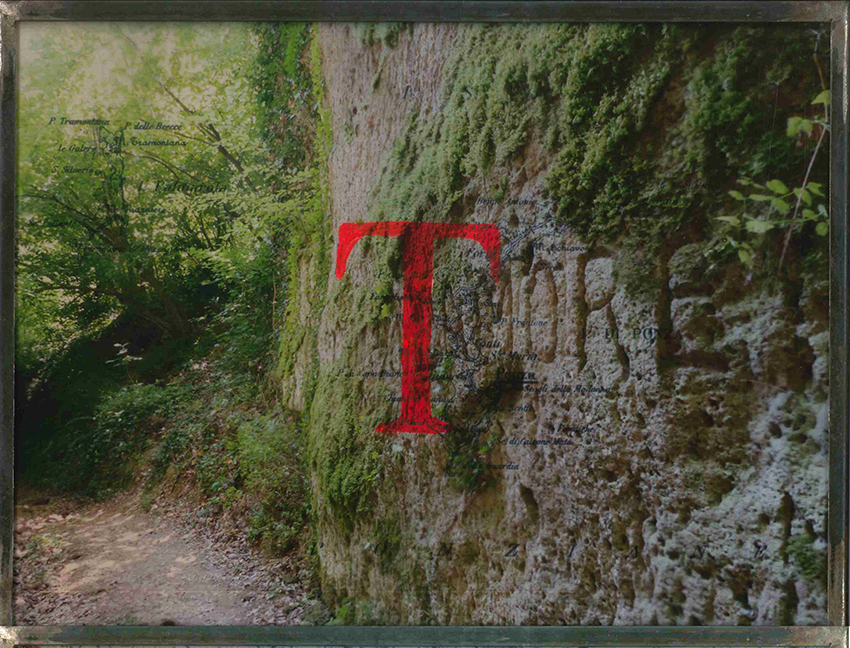

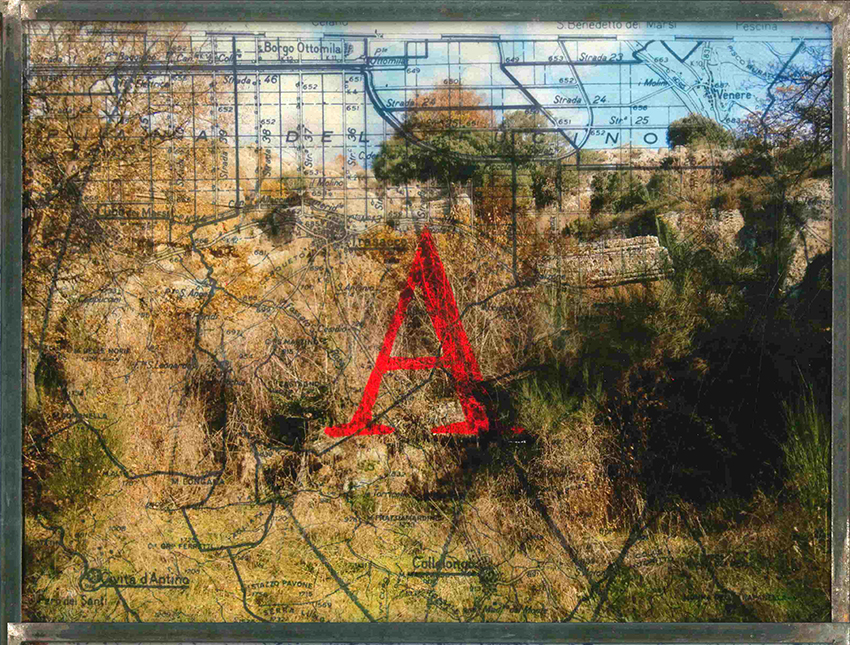

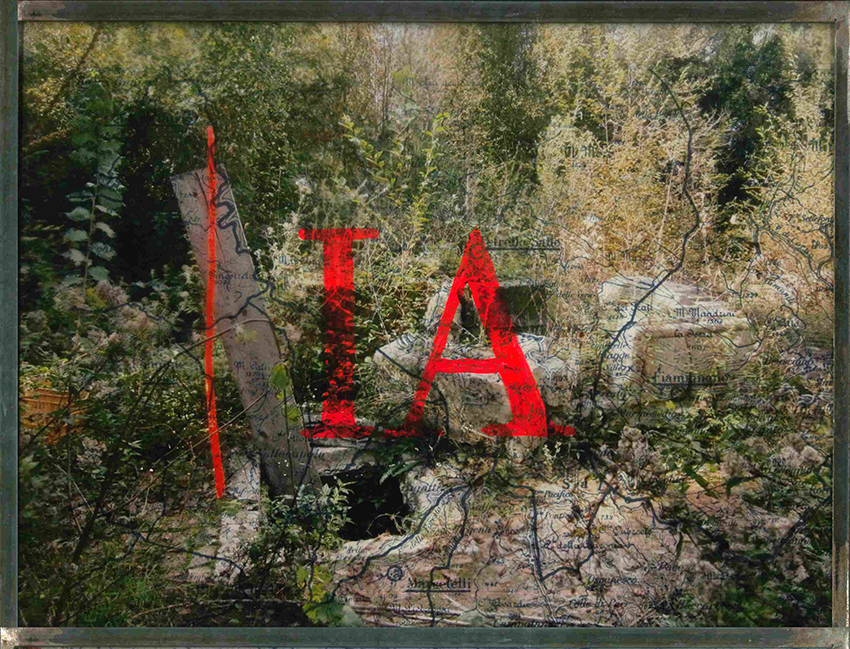

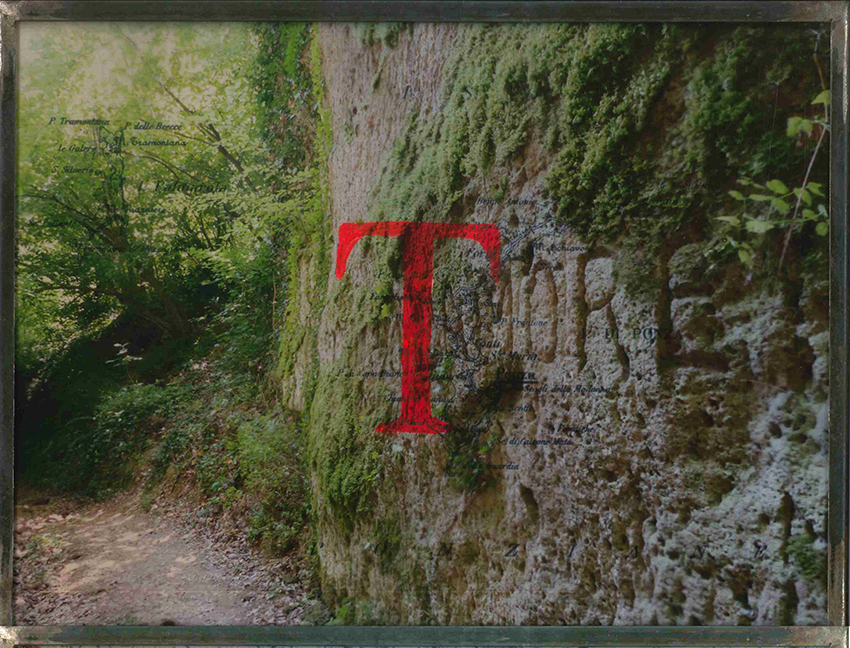

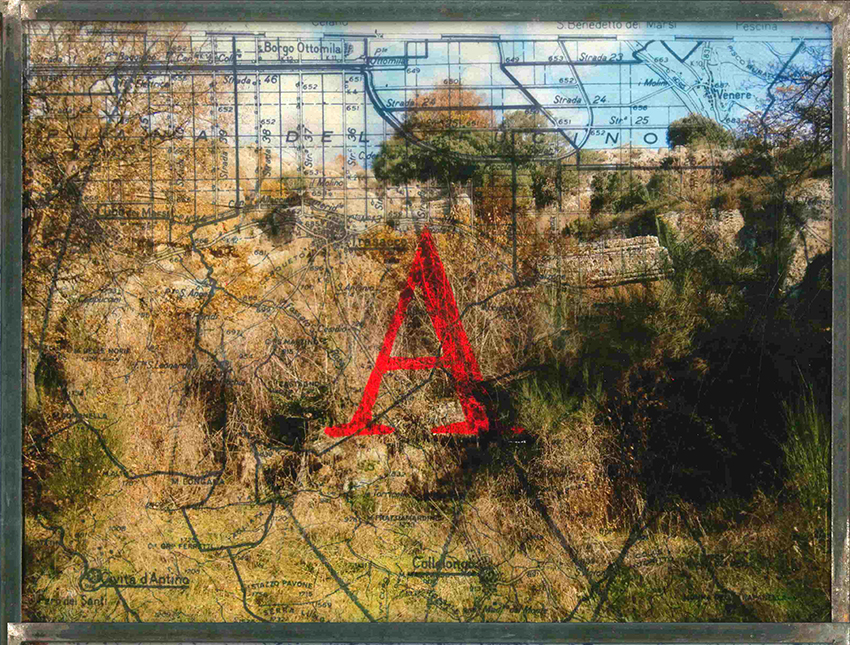

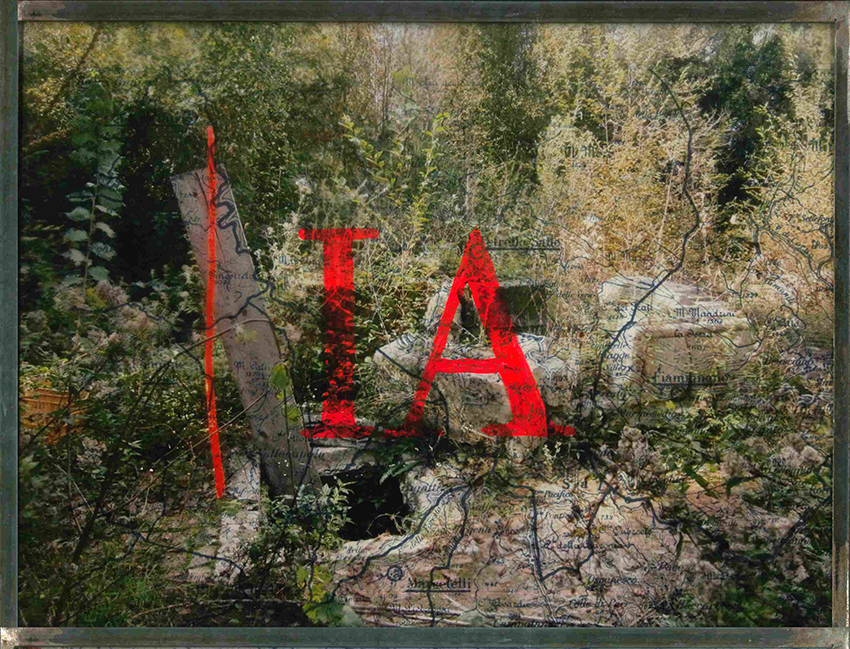

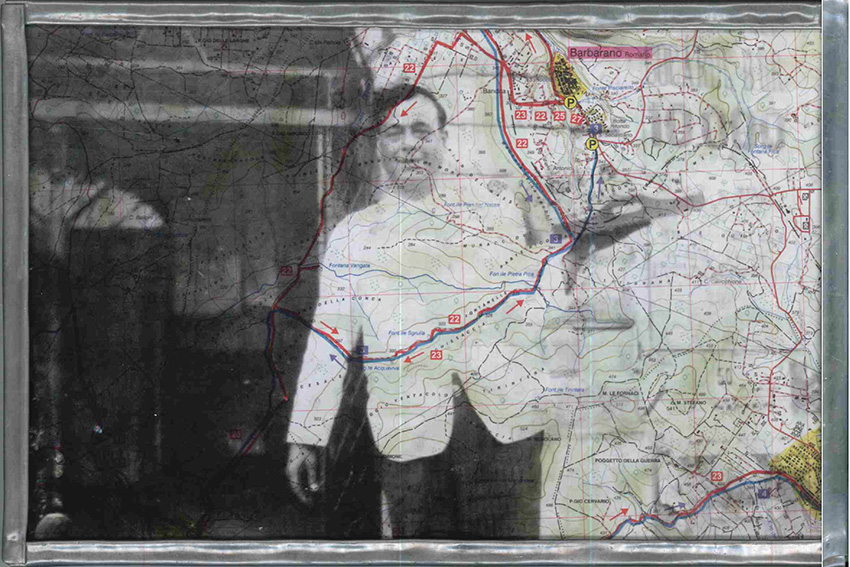

(2023, Rovine nella Selva)

(2023, Rovine nella Selva)

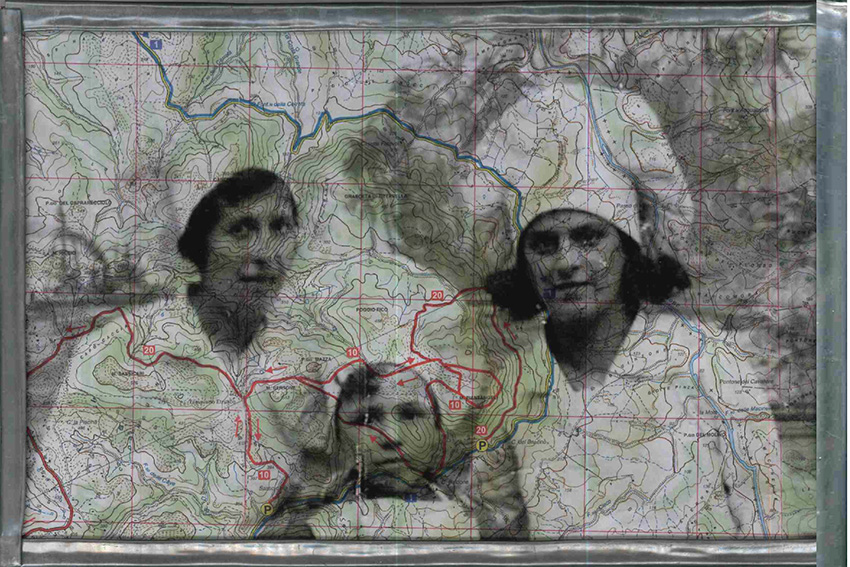

Di fronte alla serie appena descritta se ne troverebbe un’altra, simile come formato e tecnica ma di soggetto leggermente diverso. In questi altri quadri la presenza umana è più visibile. Si intravvedono nella fotografia vestigia monumentali più “strutturate”, perse nella natura, ancora riconoscibili ma sicuramente non più ricostruibili. Sullo sfondo delle fotografie trasparenti, si riconoscono mappe topografiche ritagliate e riassemblate; potrebbero o non potrebbero indicare il posizionamento di questi improbabili paradisi terrestri. Sono carte dell’Istituto Geografico Militare degli anni Cinquanta.

Su ogni mappa ho scritto una lettera, in carattere Bodoni, E, T, I, N, A, R, C, A, D, I, A, l’ultima I essendo rappresentata dall’immagine di un bastone dipinto di rosso, piantato nel suolo della diruta cattedrale di Castro. L’ultima parola della famosa citazione del Guercino e di Poussin, EGO, è sovrapposta all’immagine di una tomba principesca d’Etruria, la Cuccumella a Vulci.

Mi provo qui a oscillare fra una certa “bellezza” dell’immagine e il suo carattere ammonitore. Niente vi cerco di spettacolare o di drammatico, ma penso aleggi da quelle parti una qualche inquietudine: un sentimento che ci accomuna e ci fa “umana cosa”.

.

Otto. Monstrum nostrum

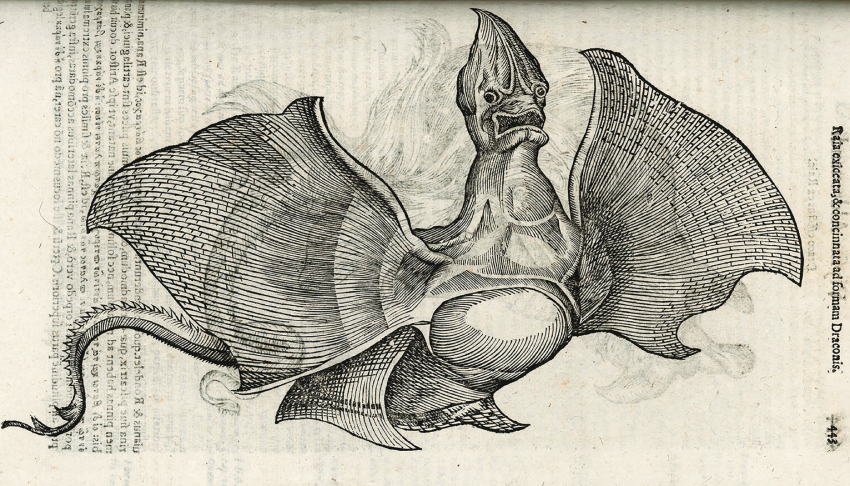

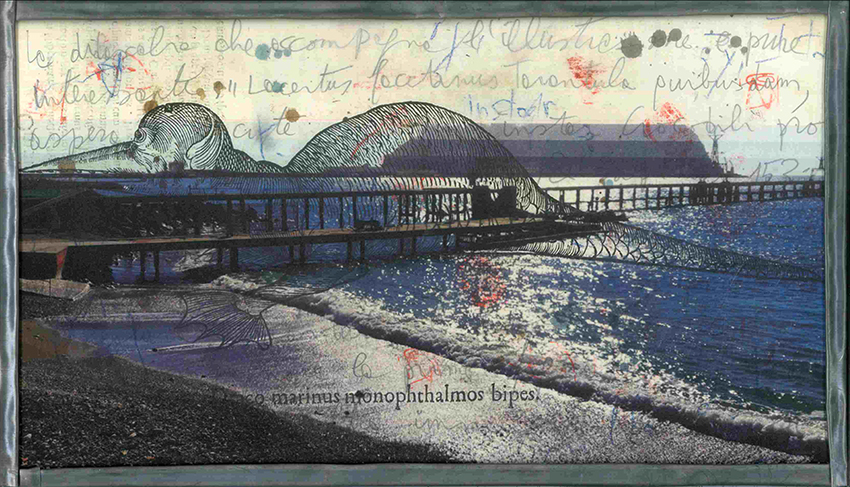

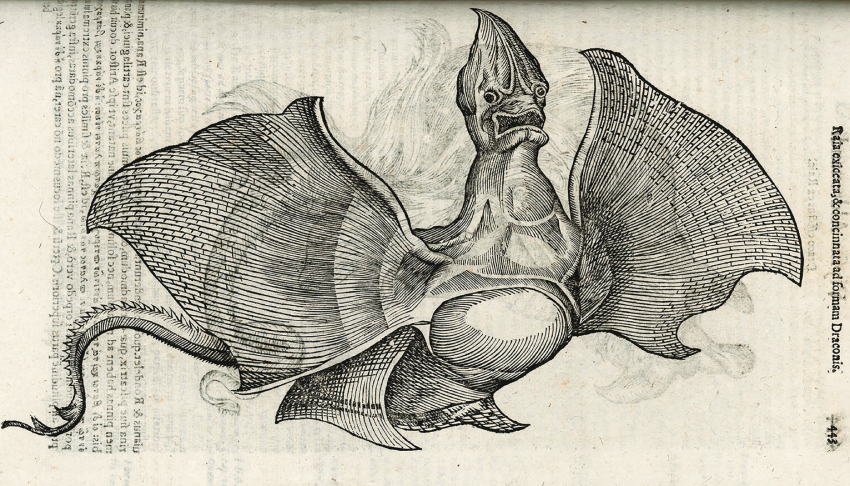

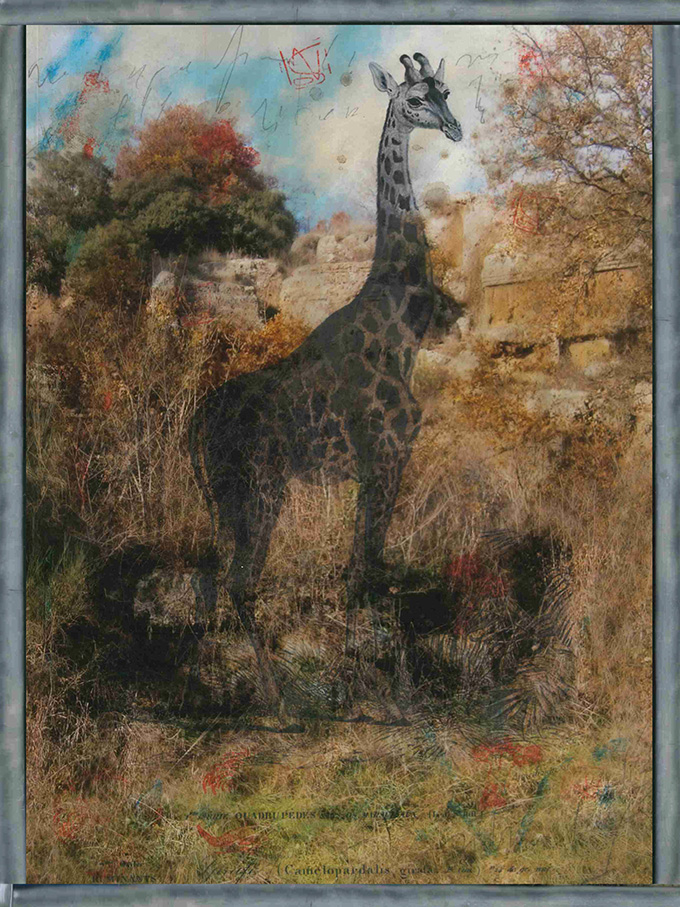

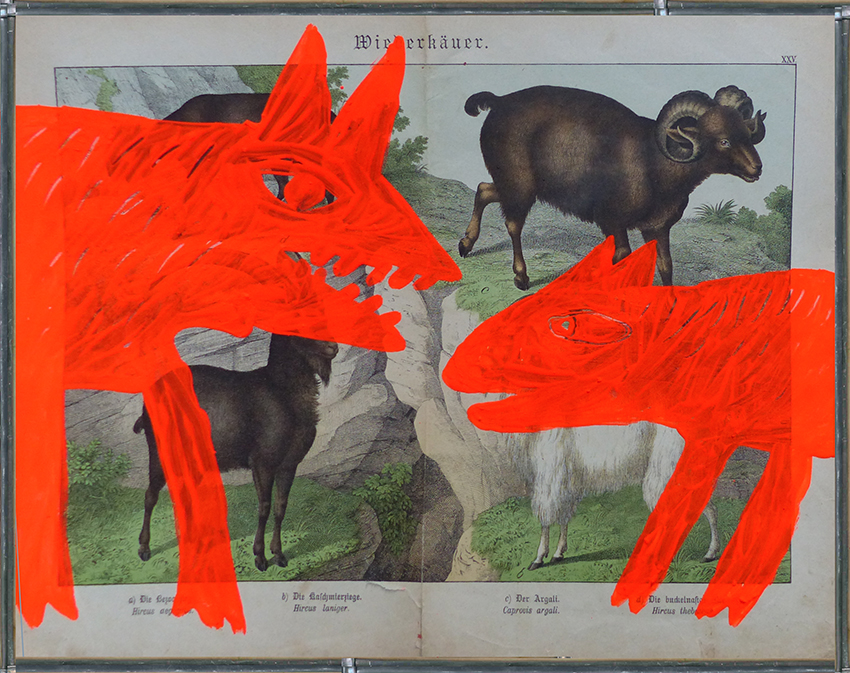

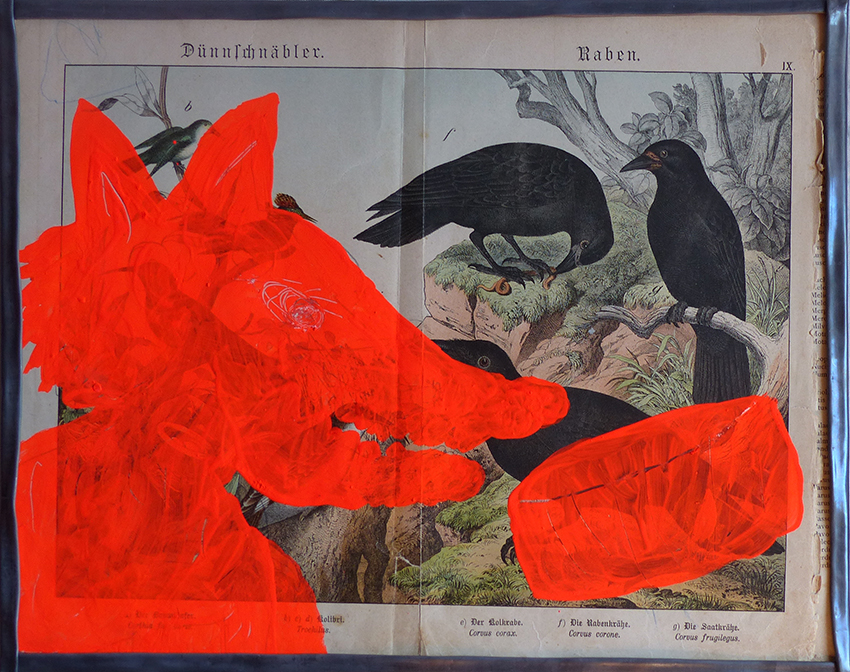

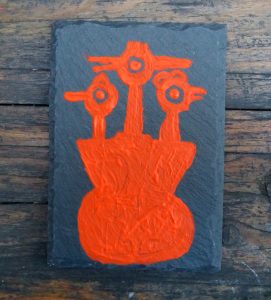

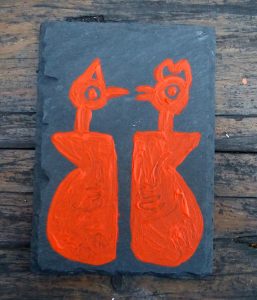

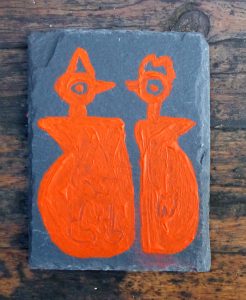

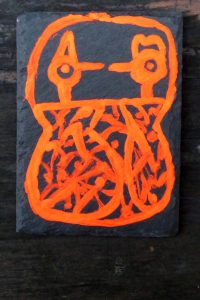

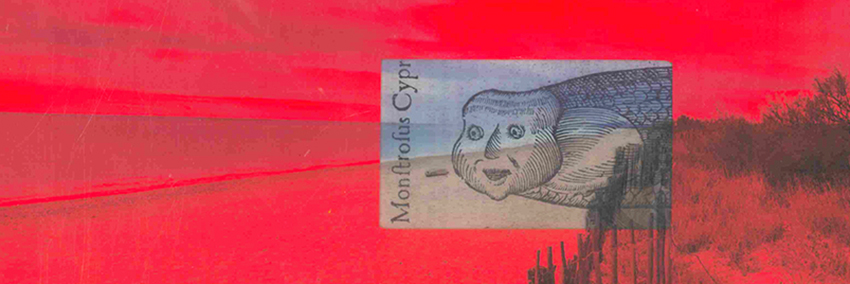

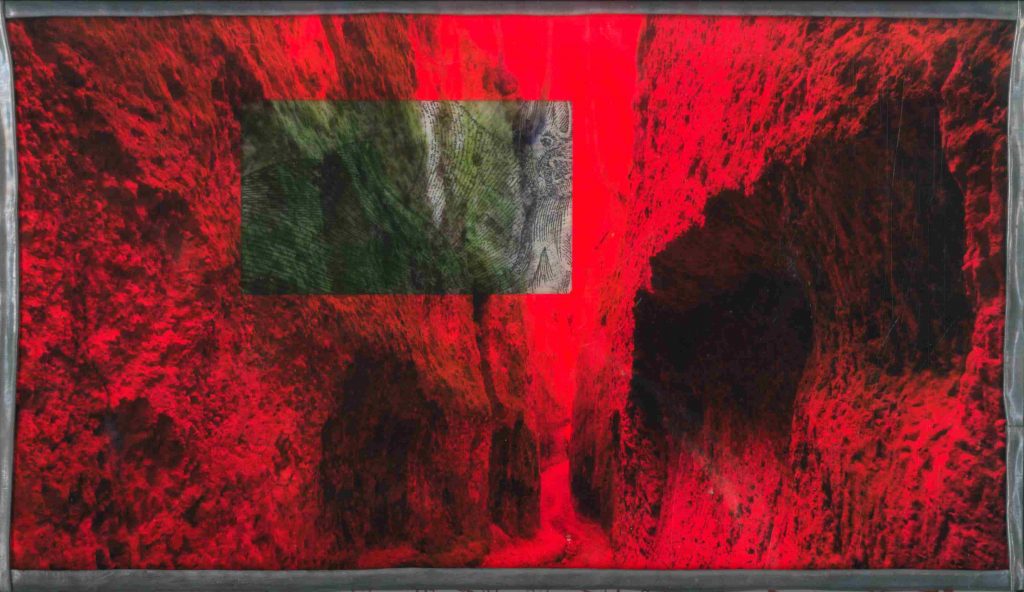

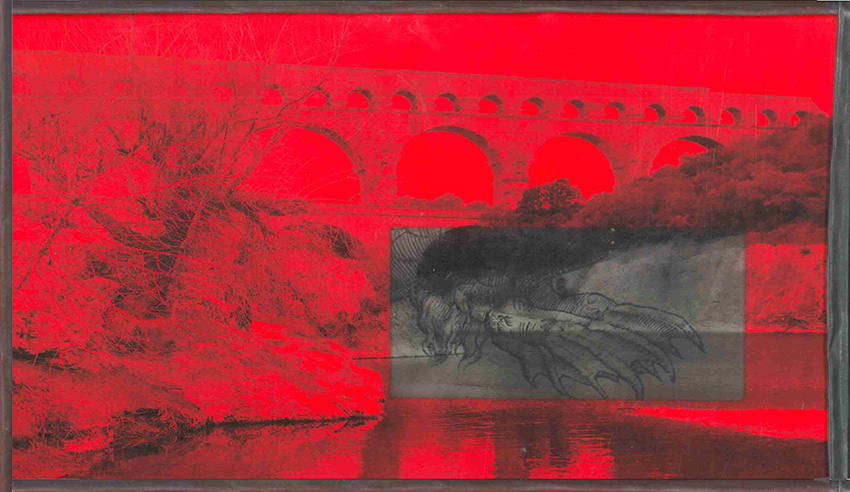

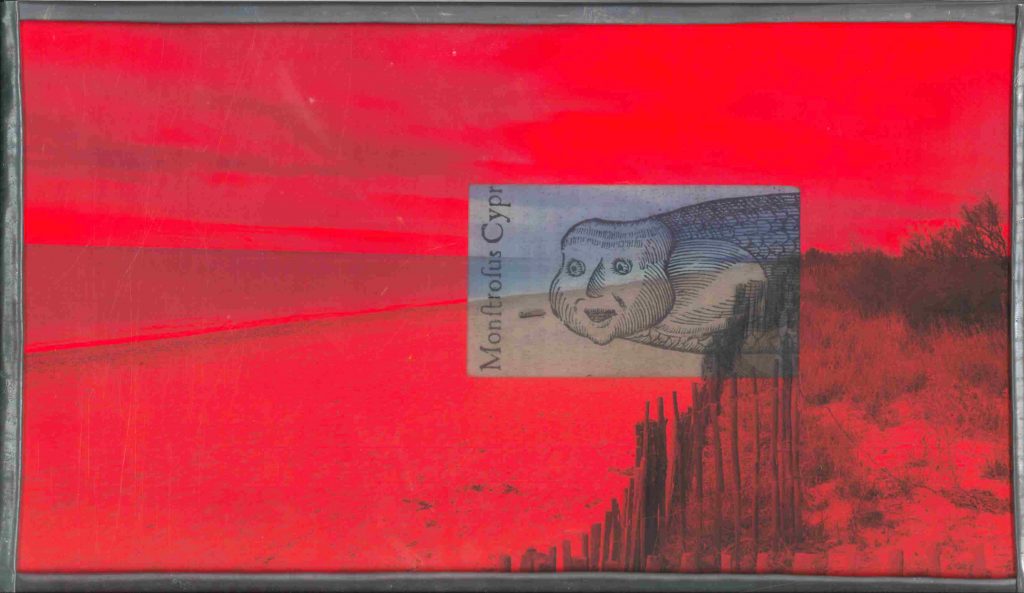

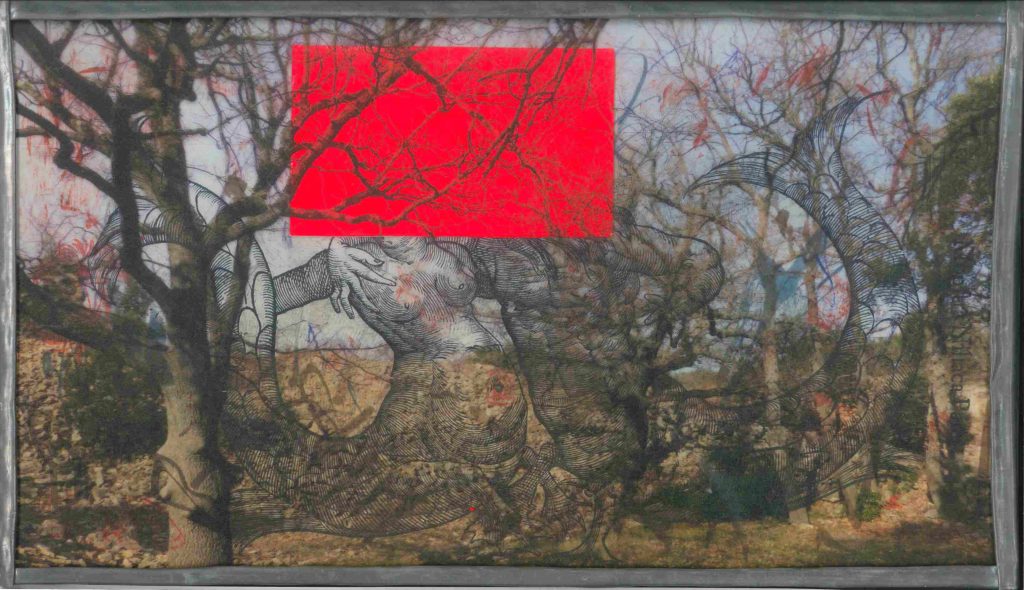

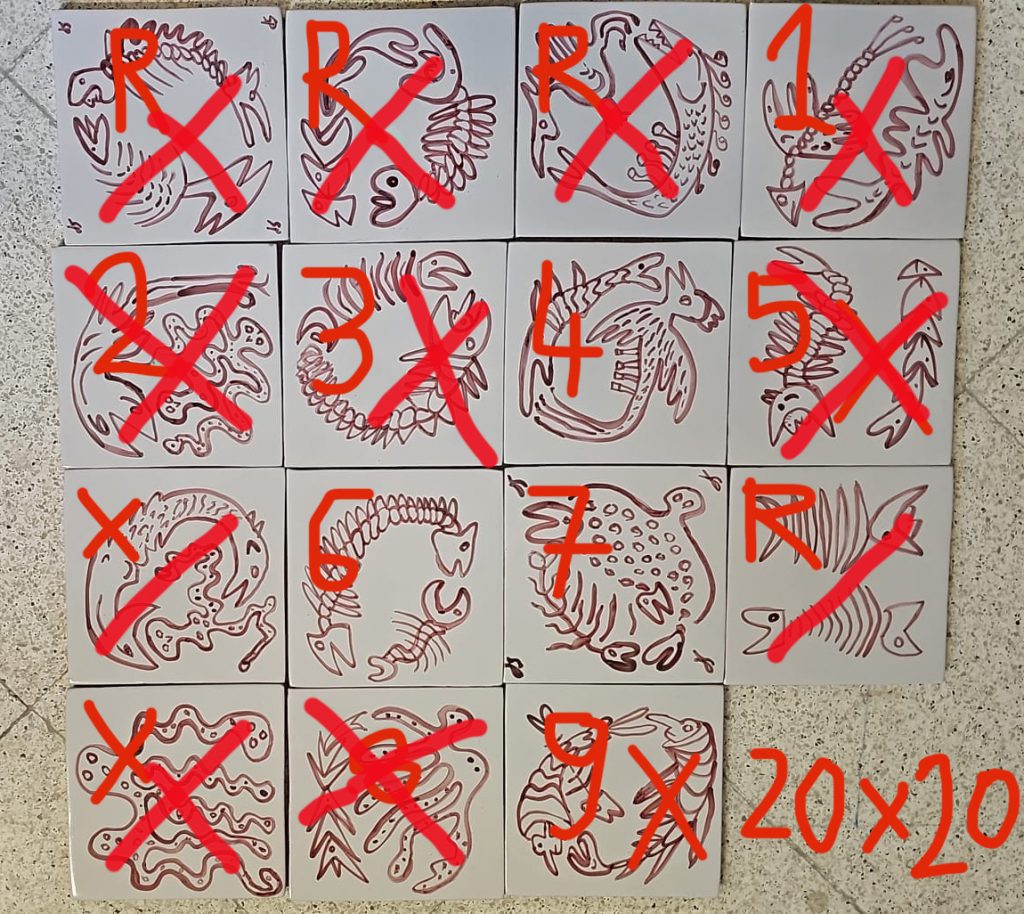

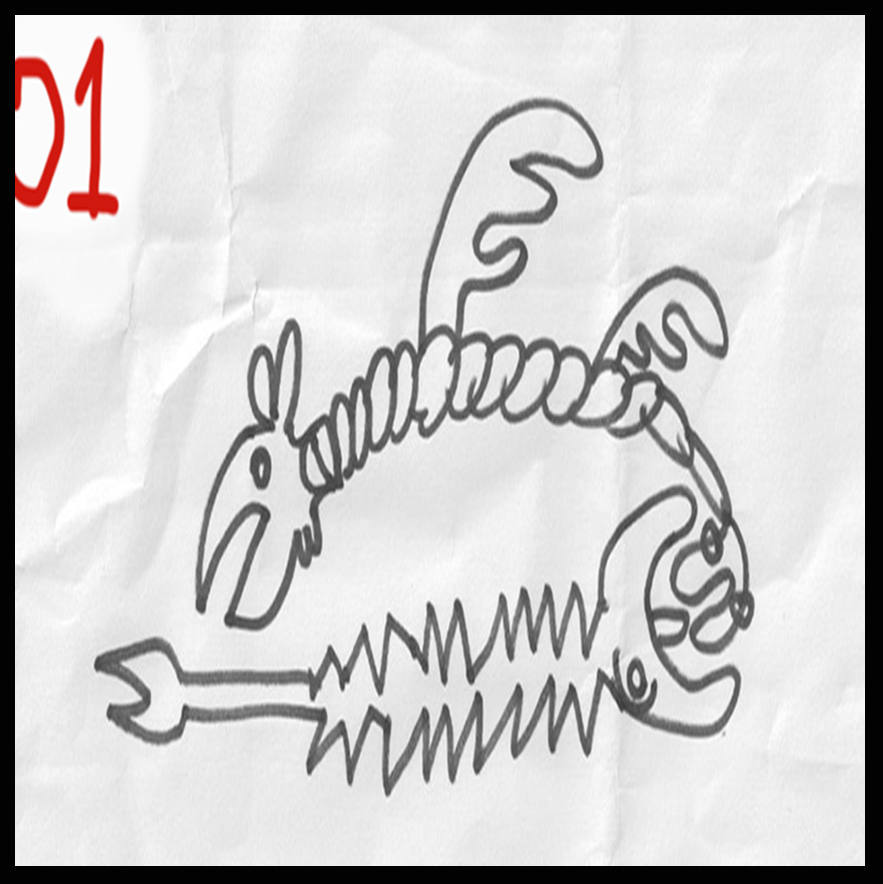

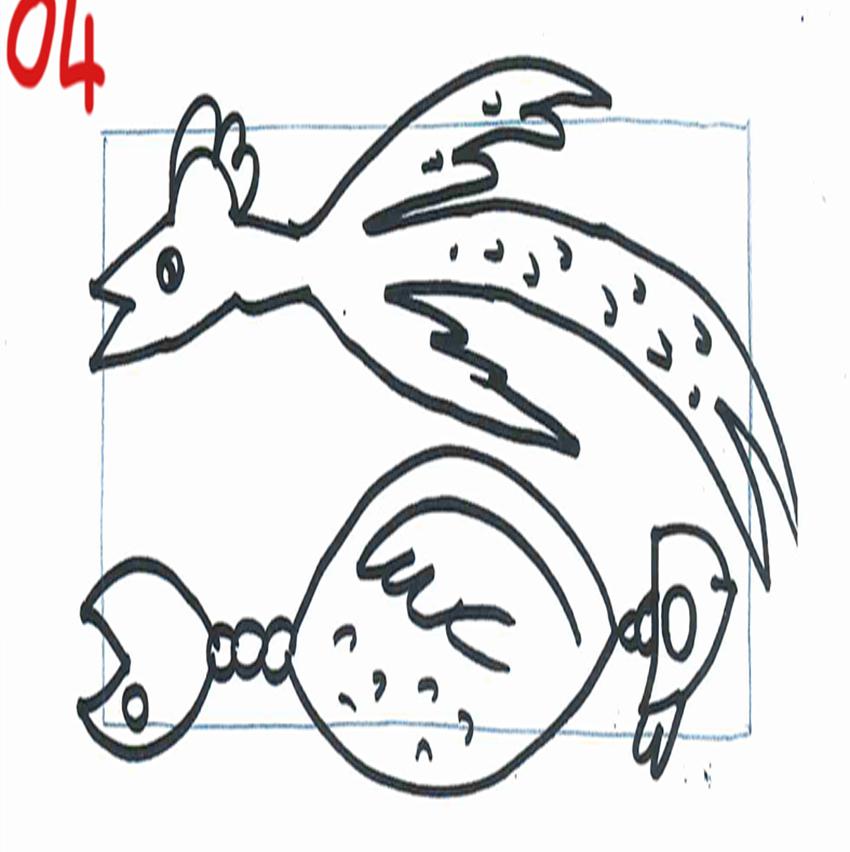

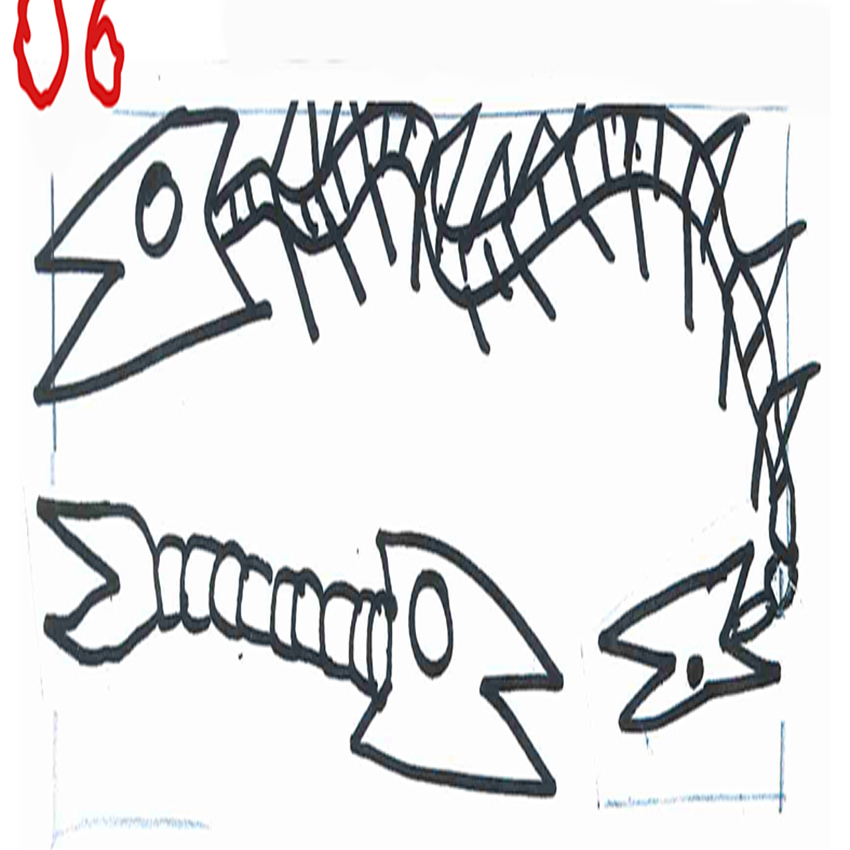

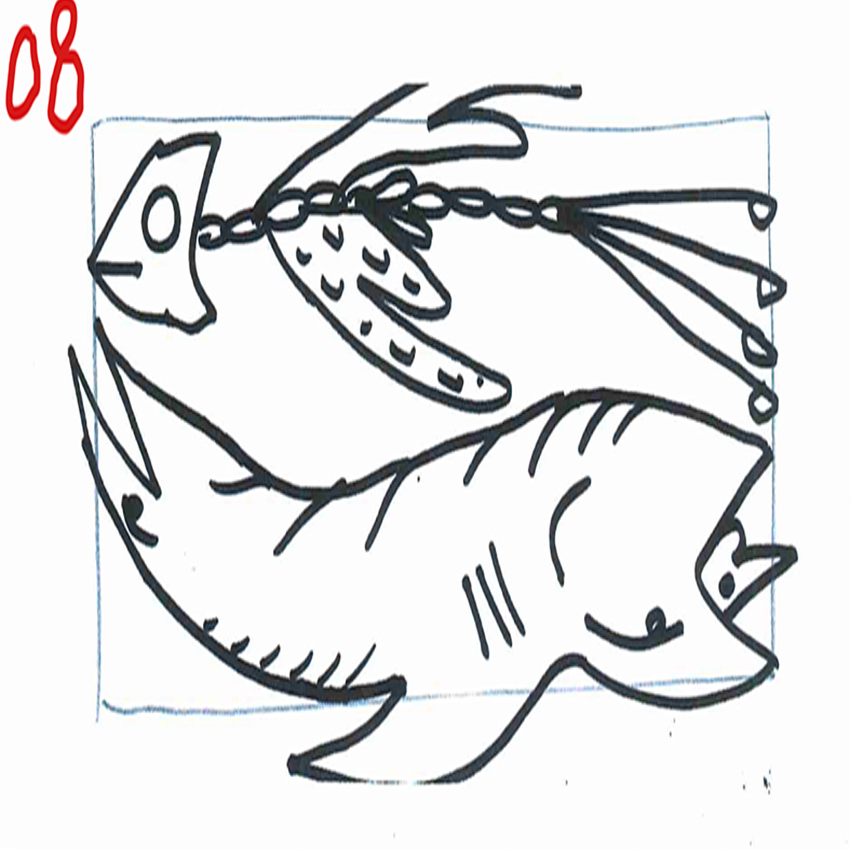

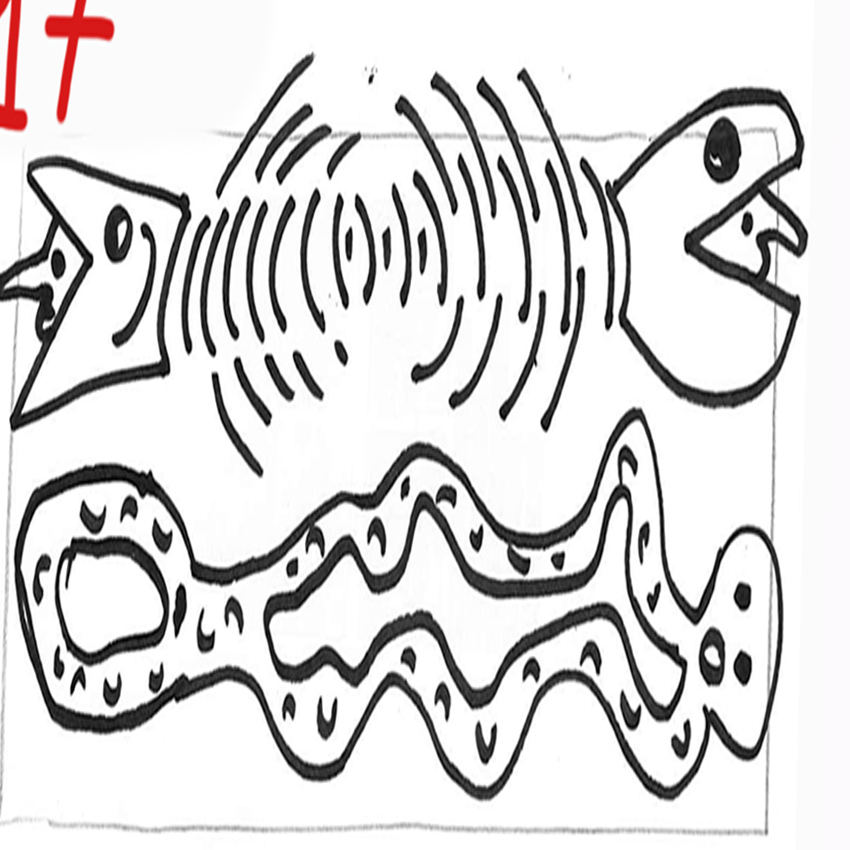

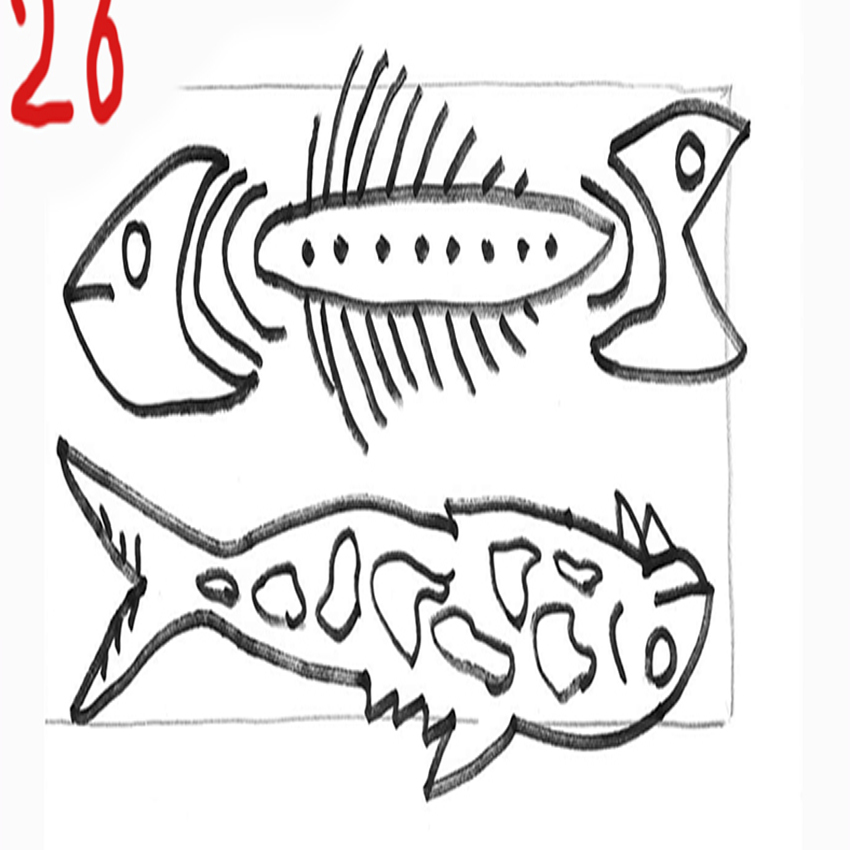

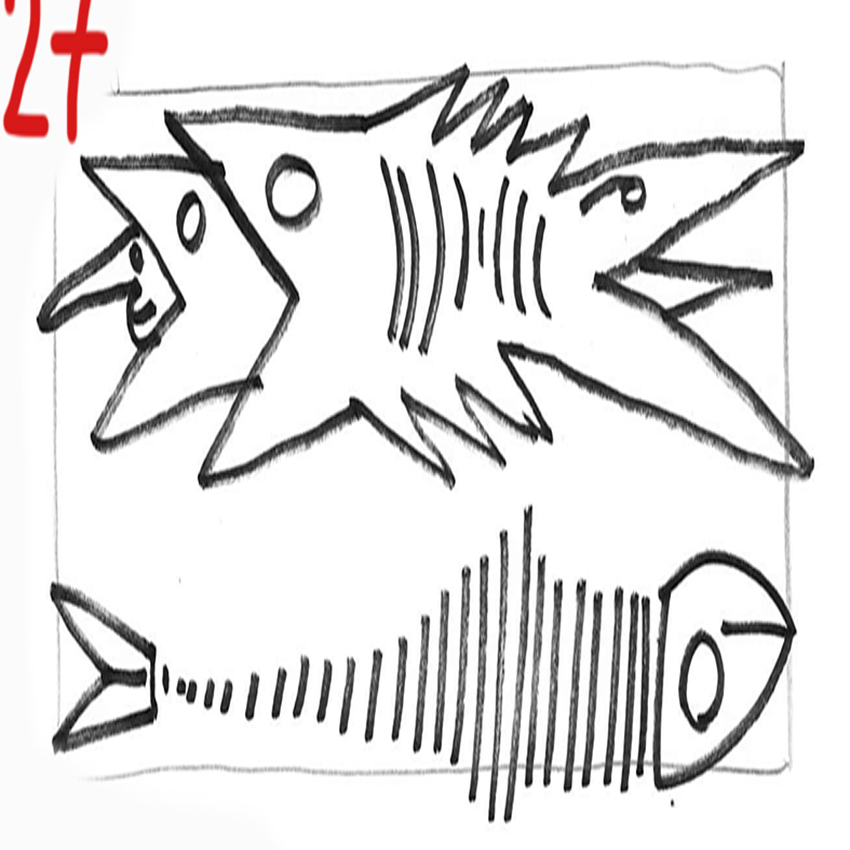

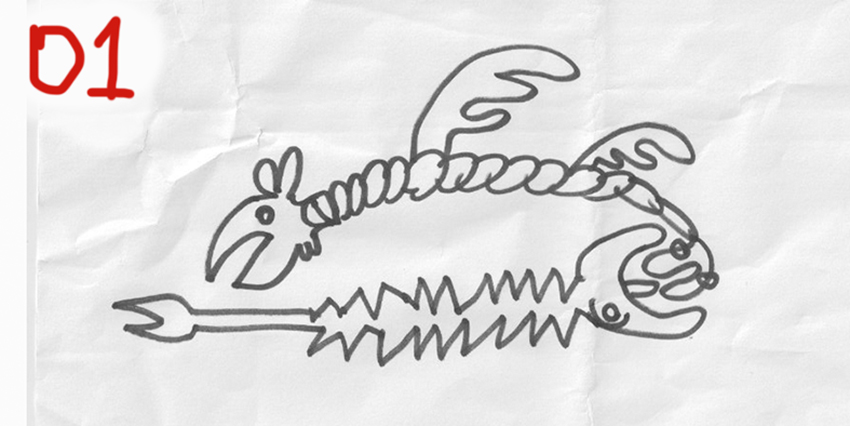

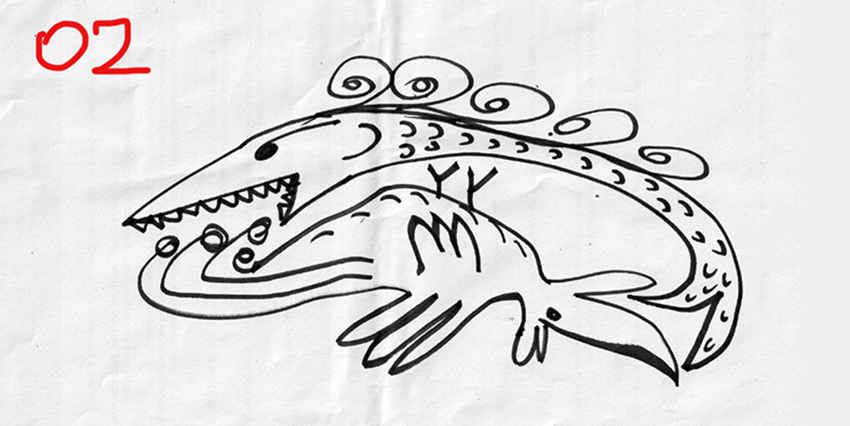

(2021, Histoire des monstres 00)

(2021, Histoire des monstres 00)

.

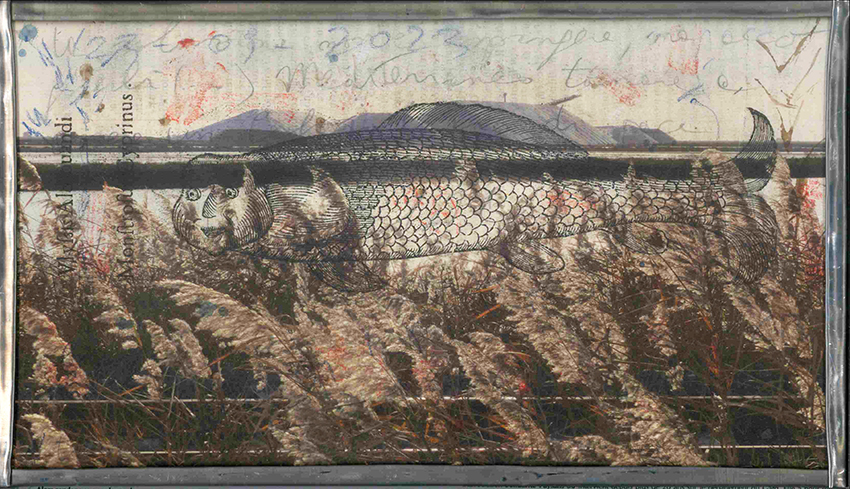

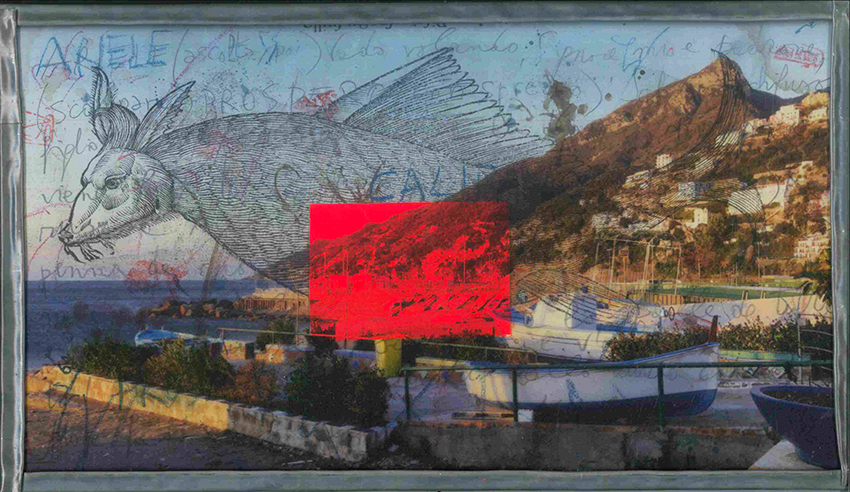

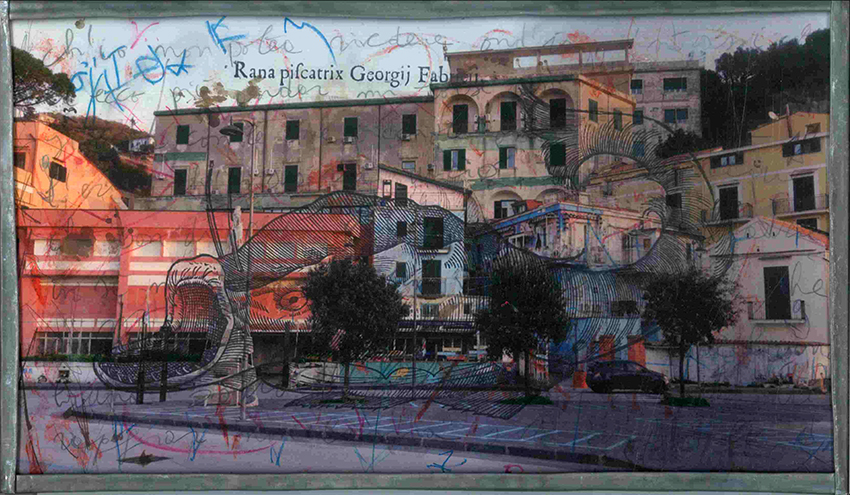

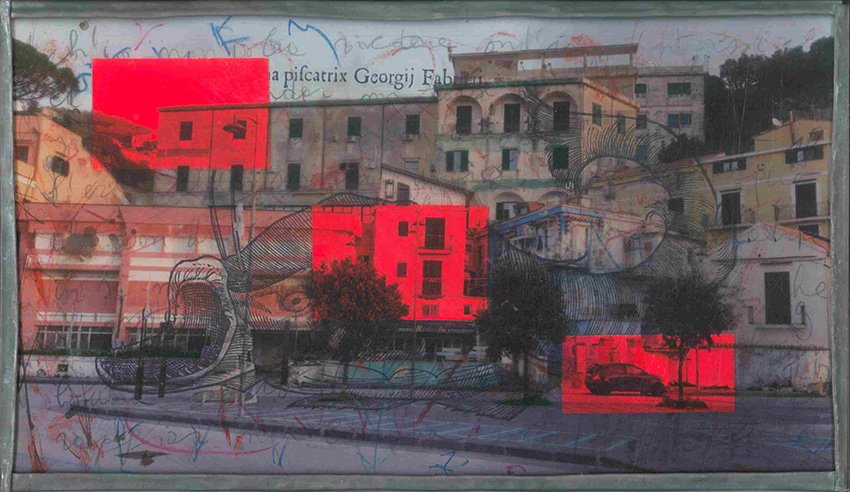

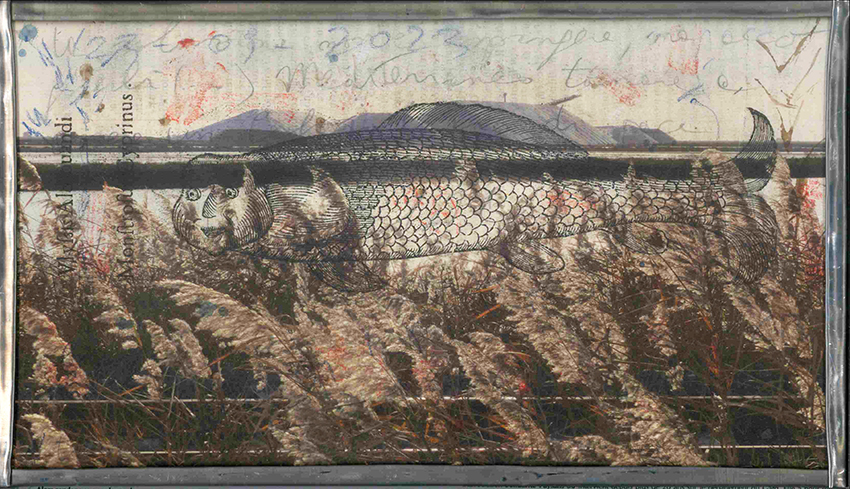

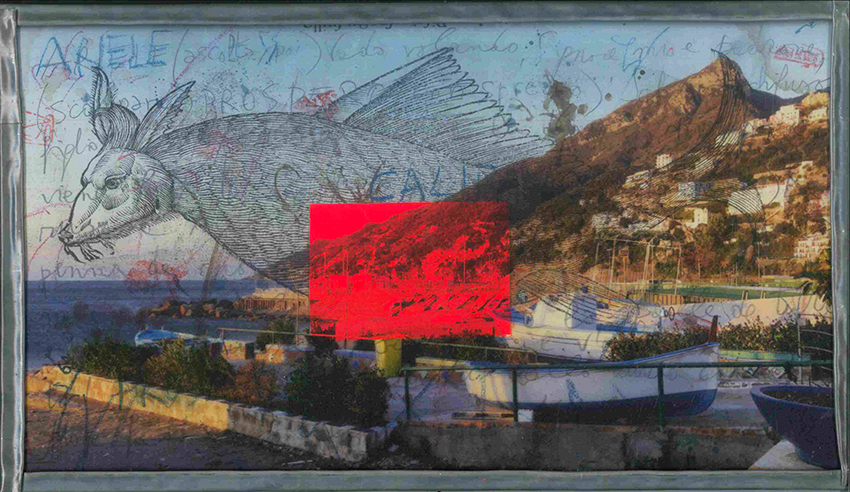

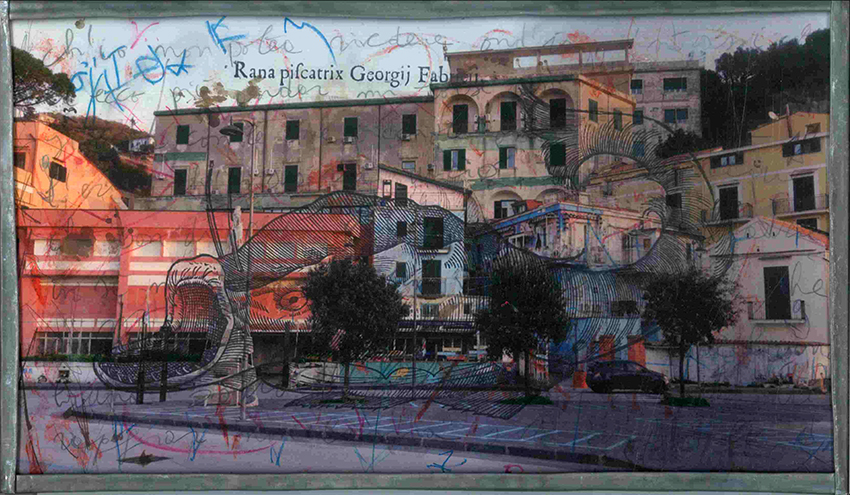

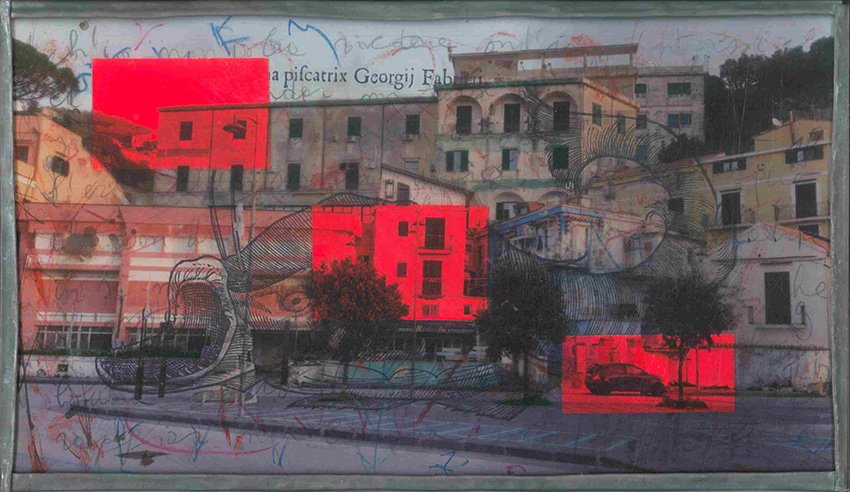

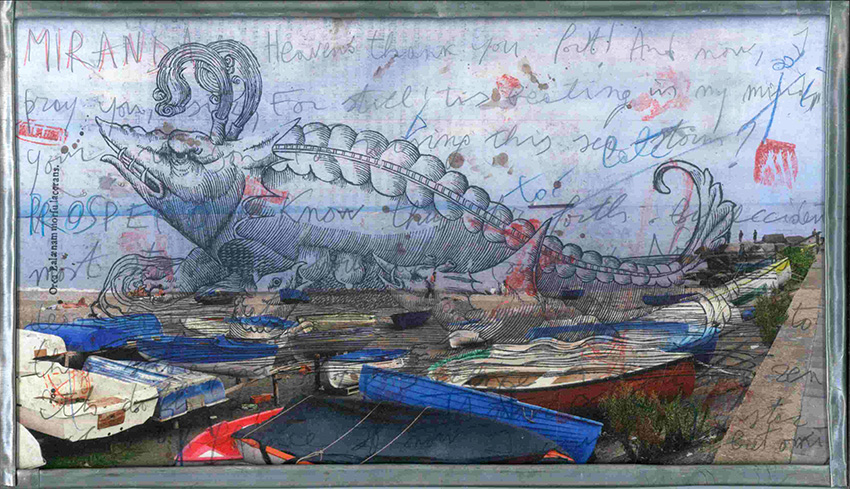

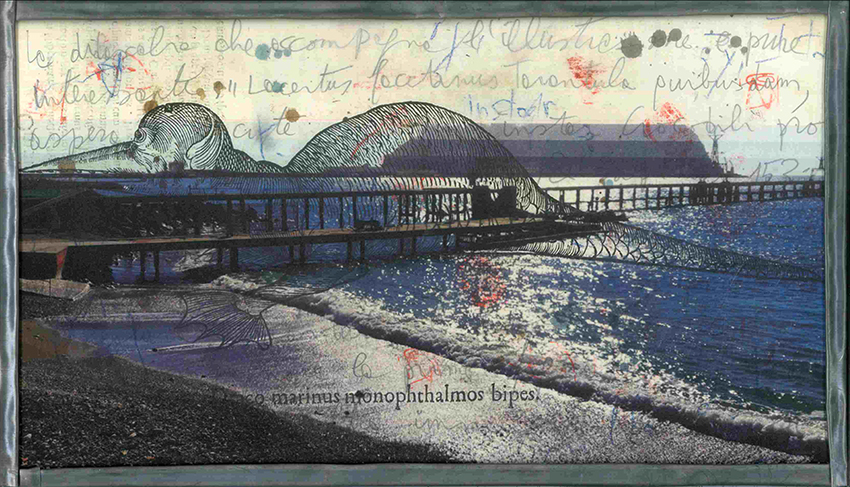

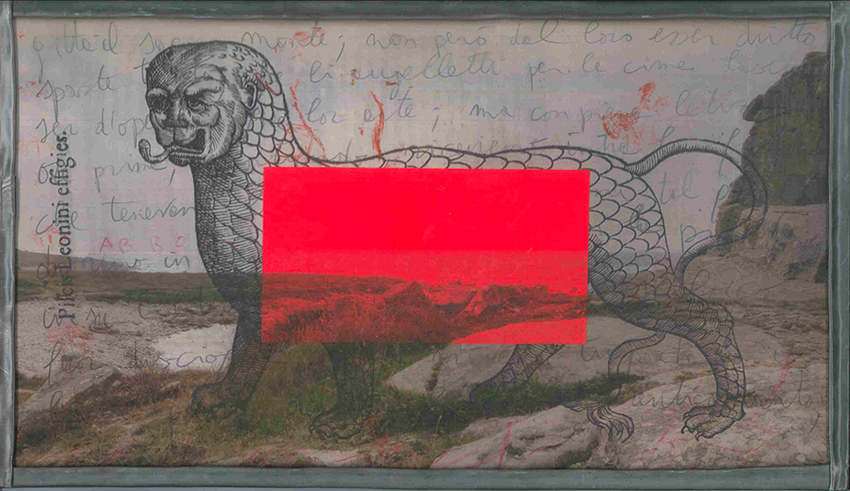

Dicembre 2021.

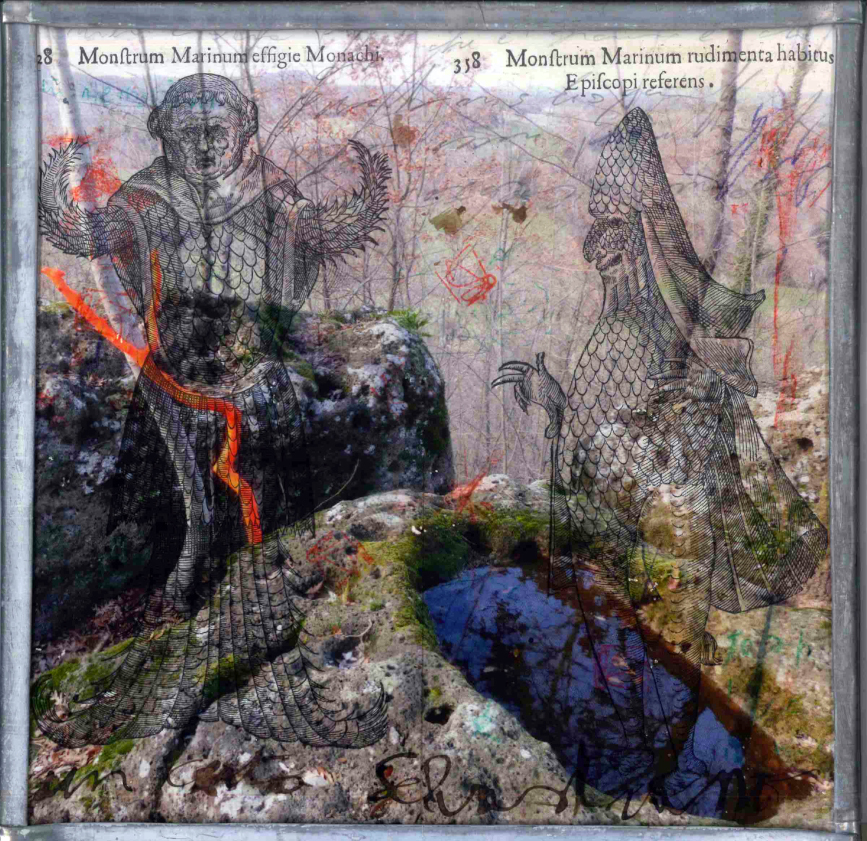

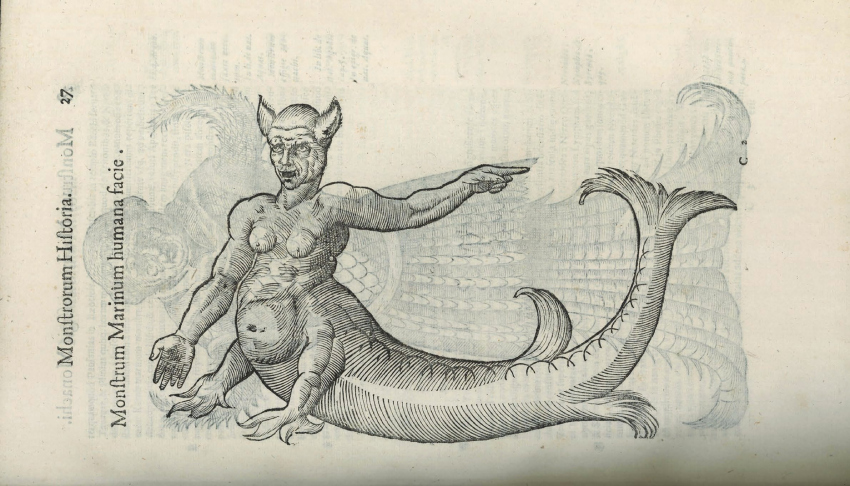

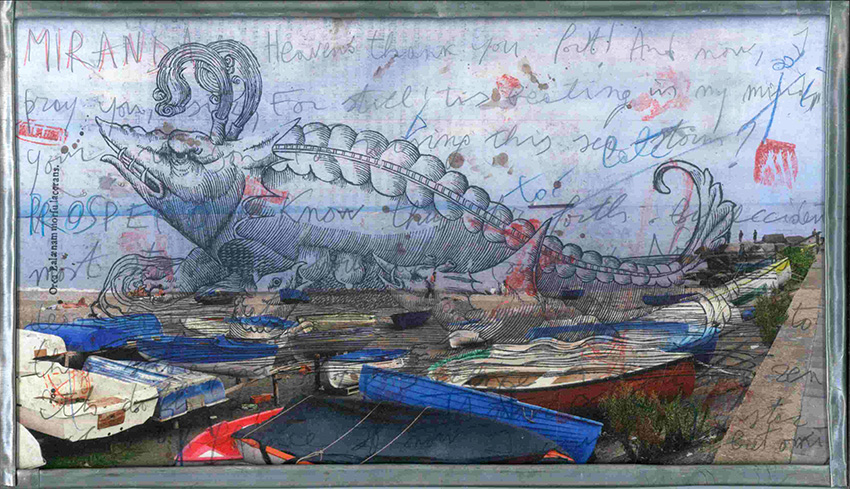

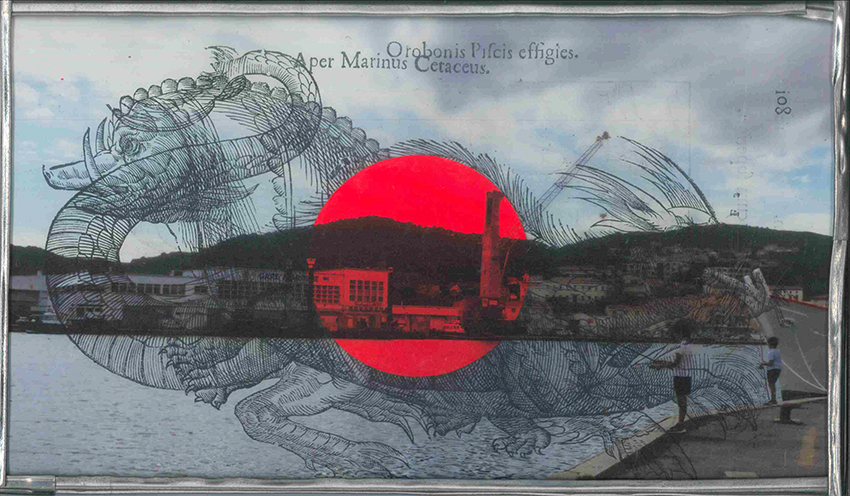

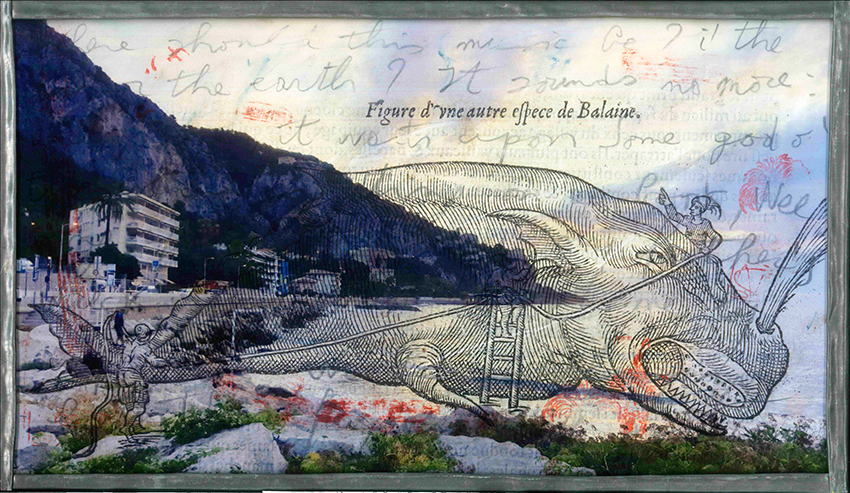

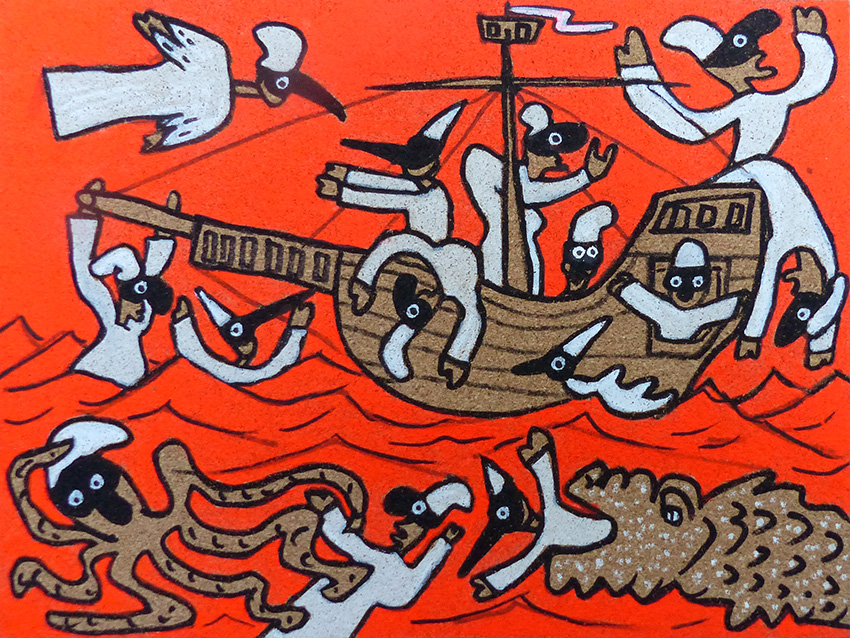

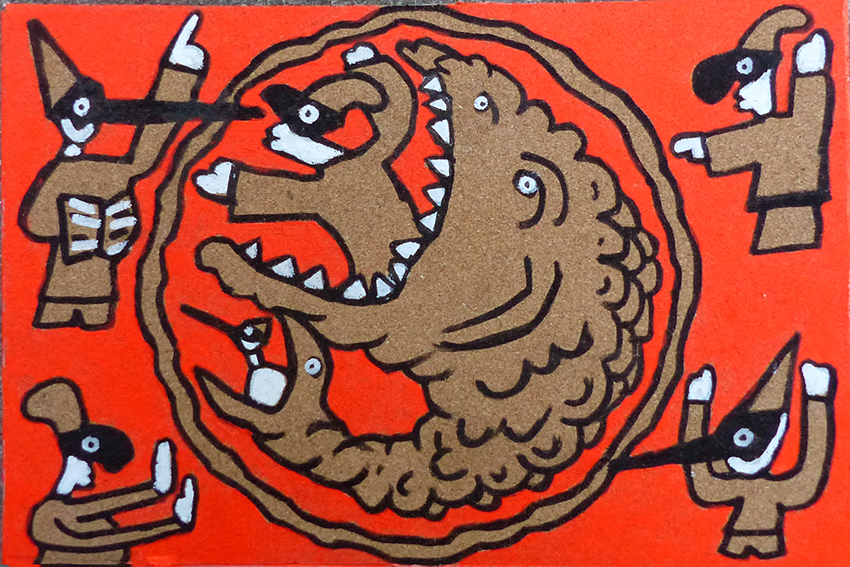

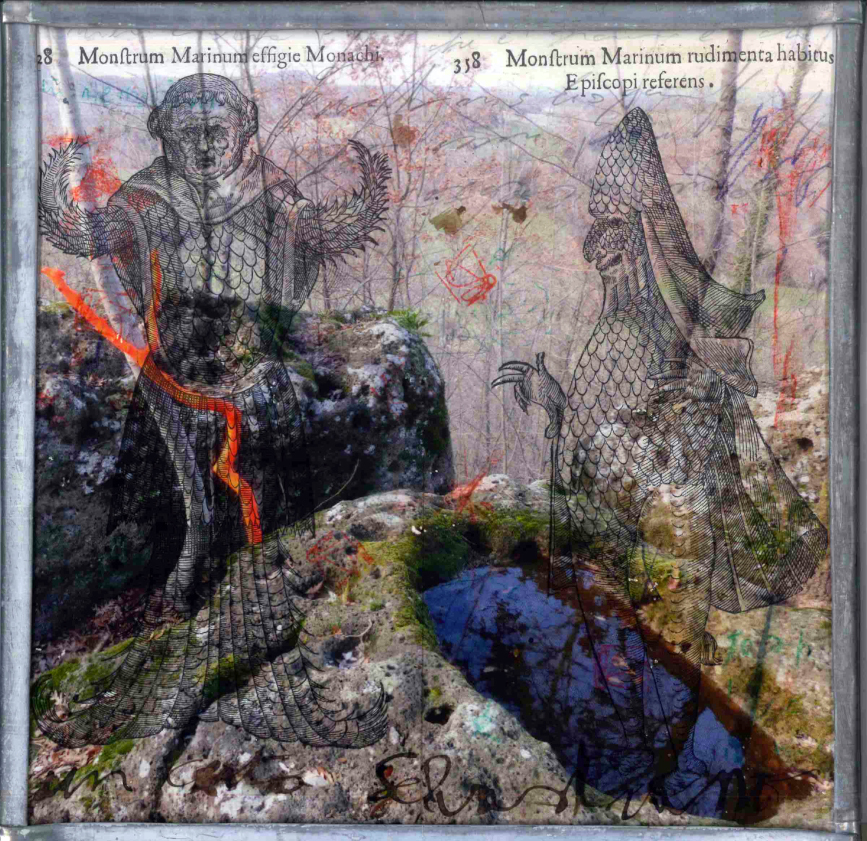

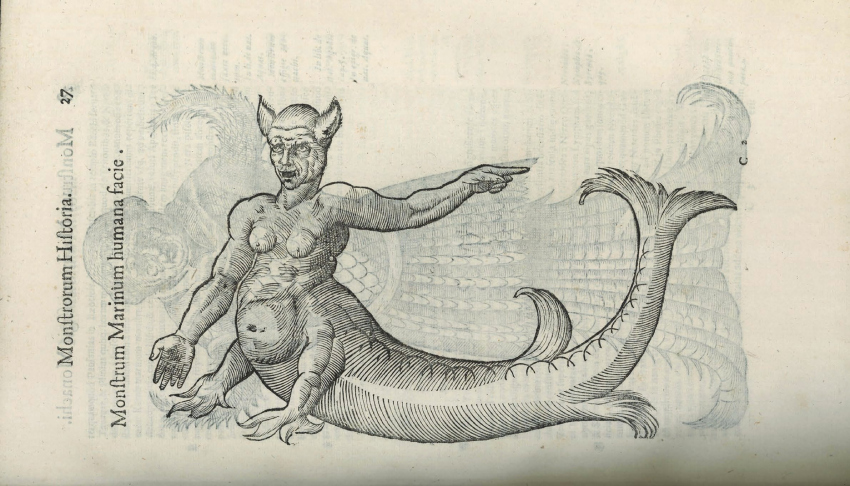

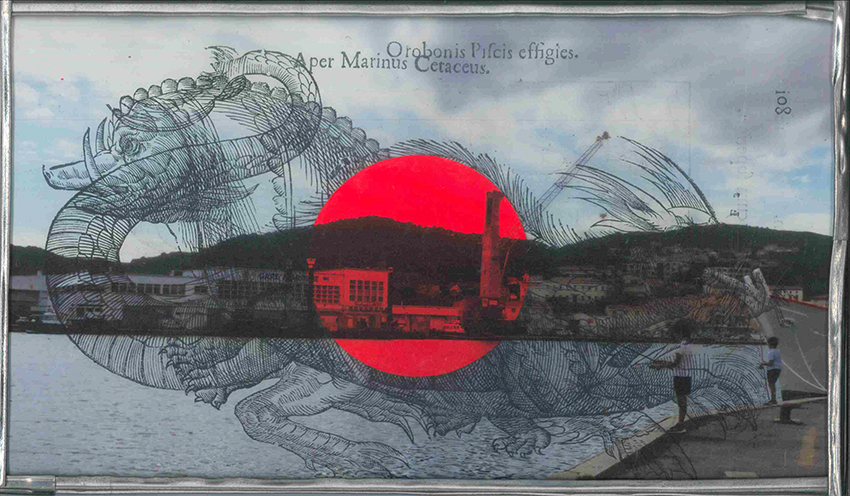

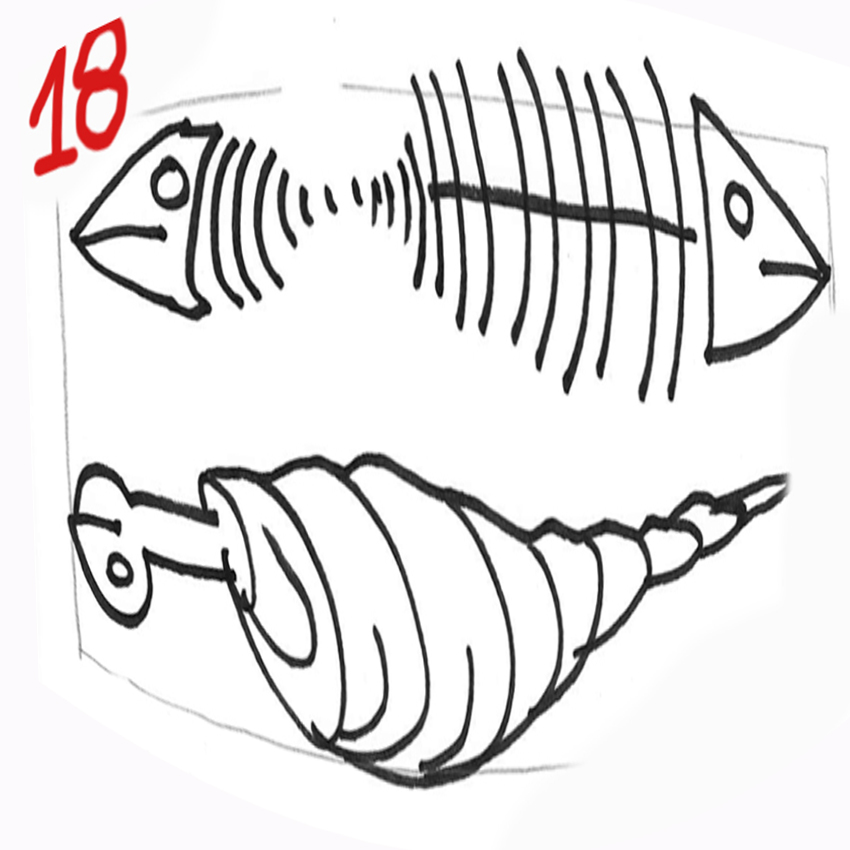

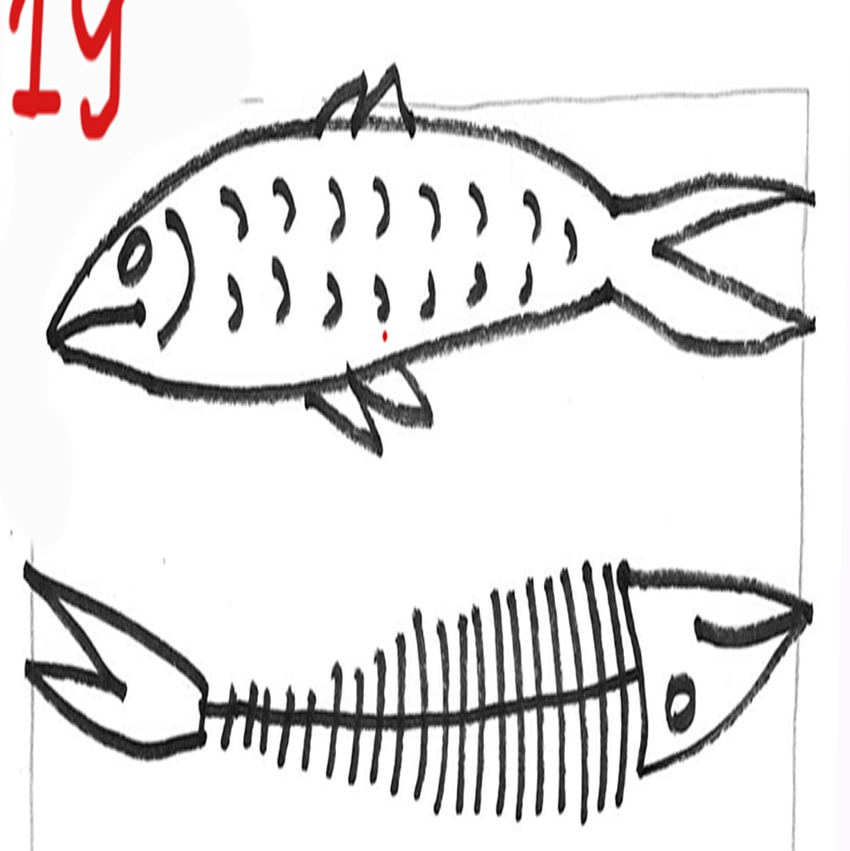

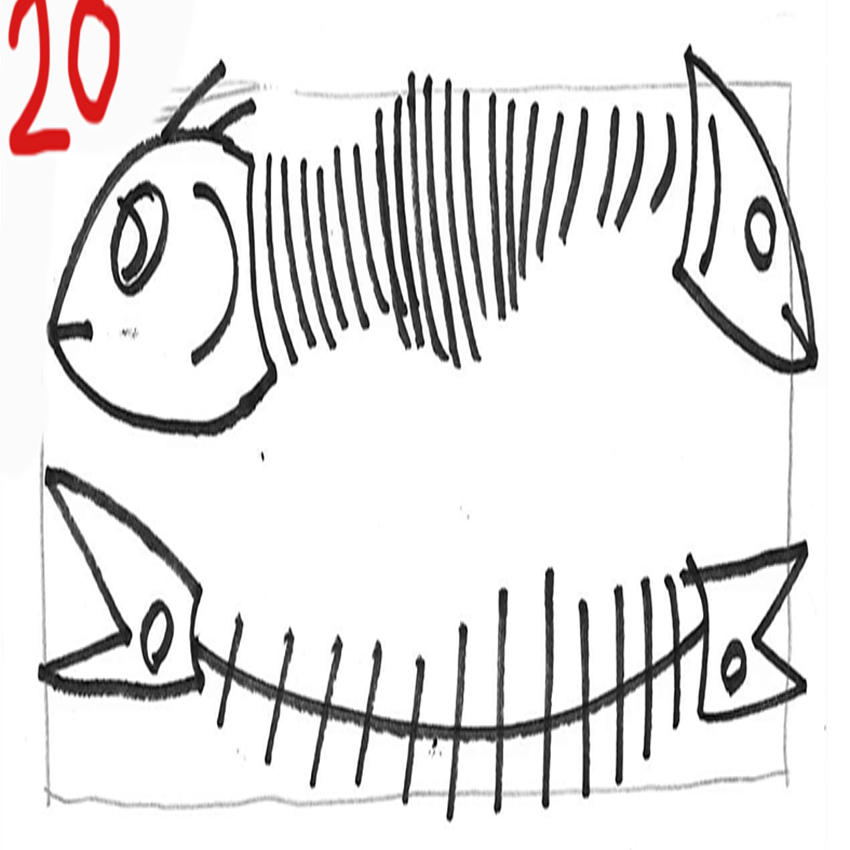

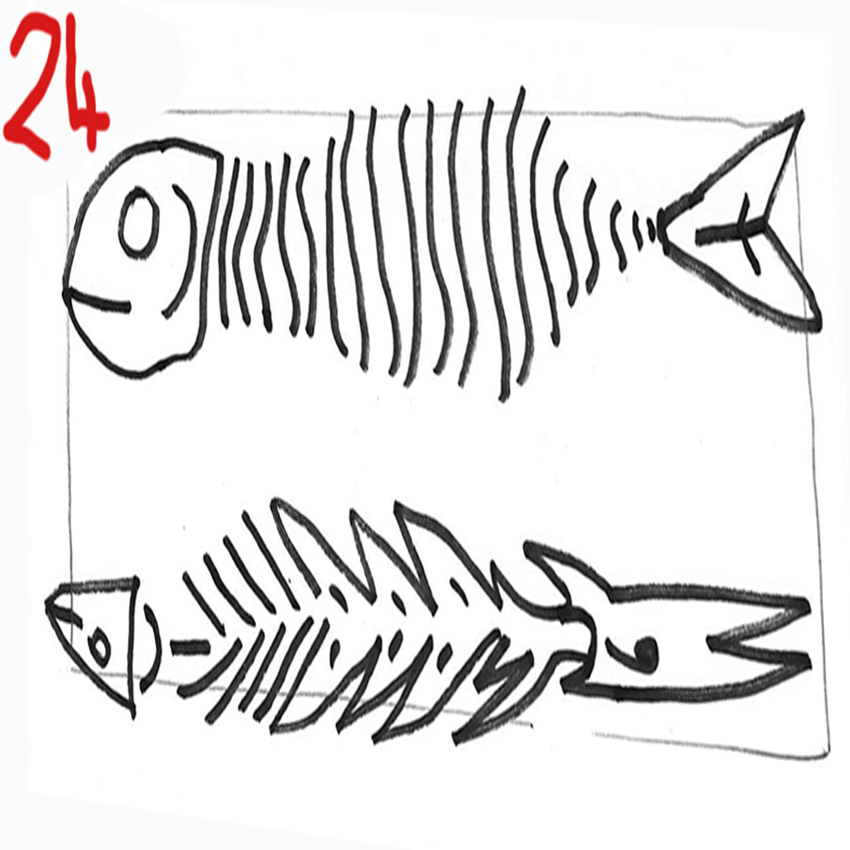

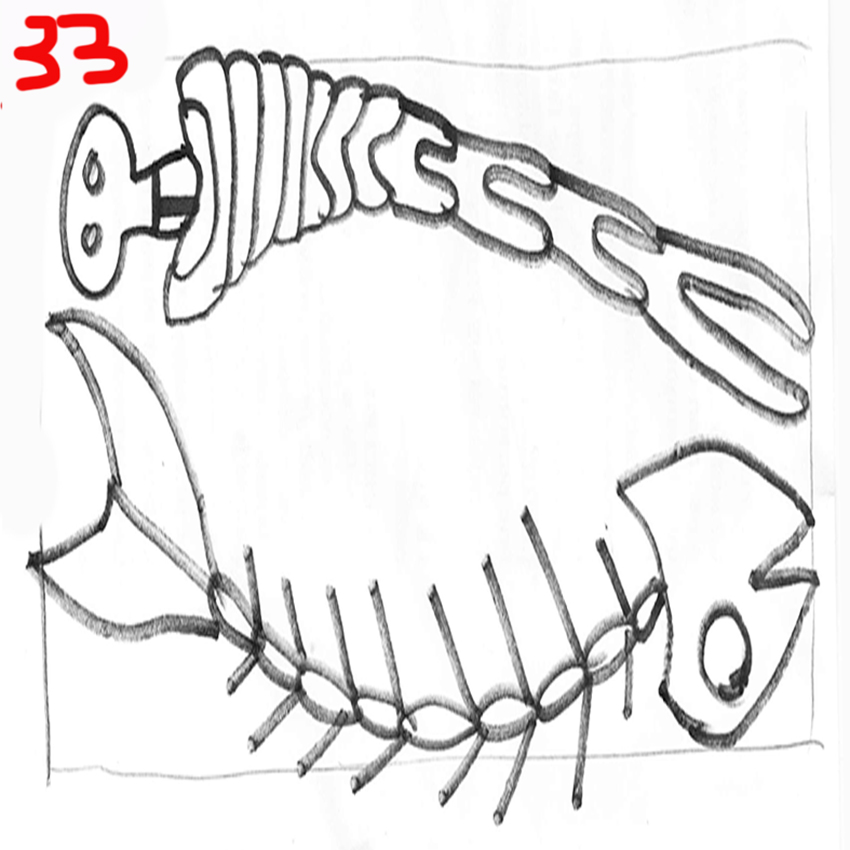

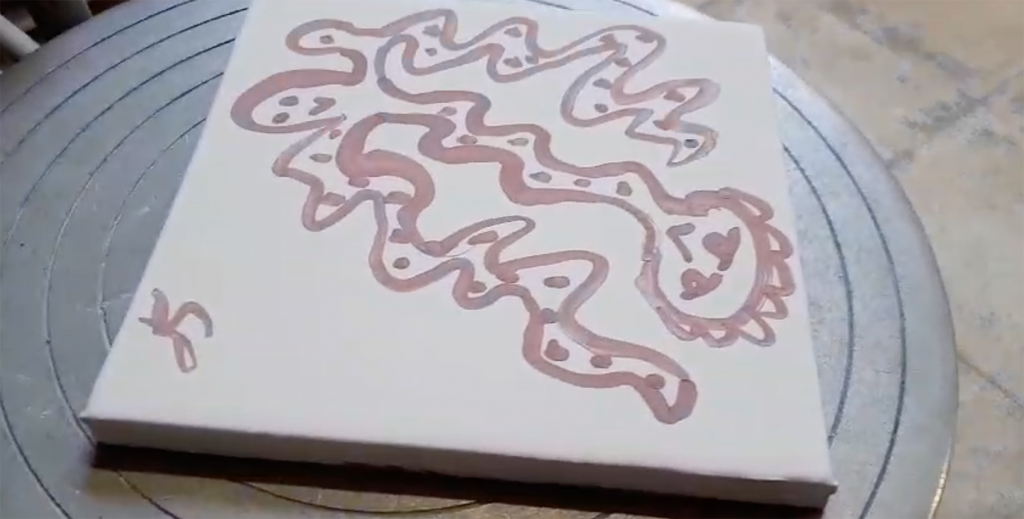

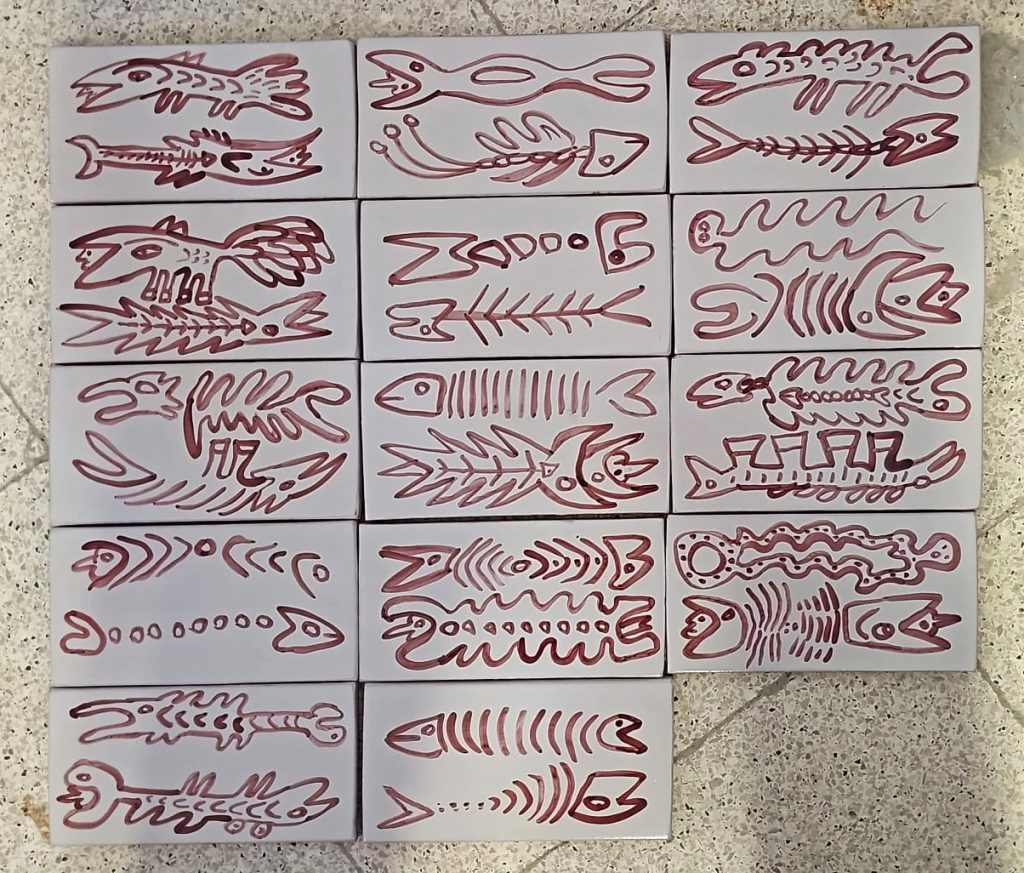

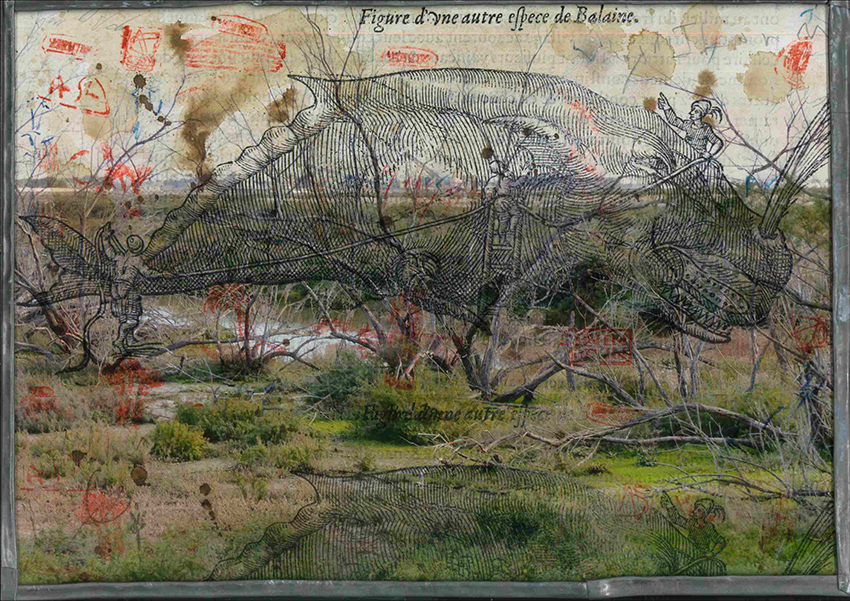

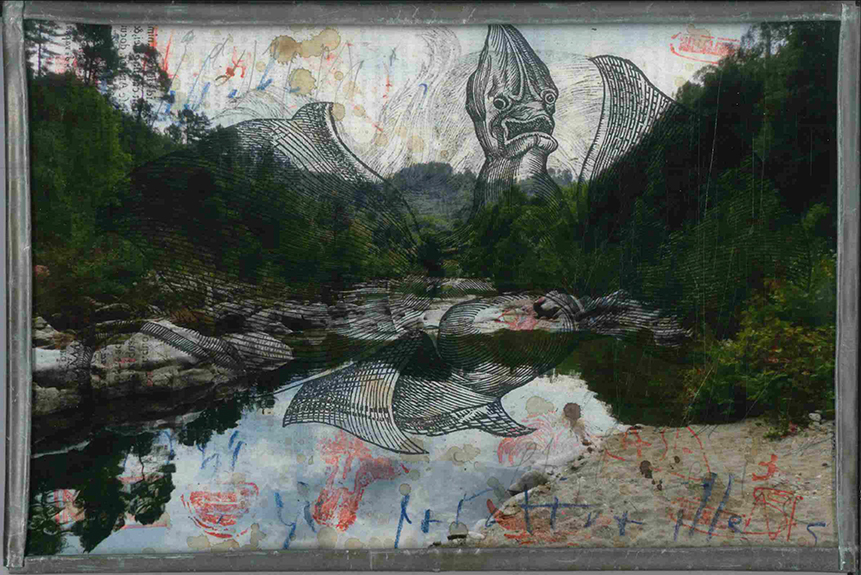

È stato nell’attesa di un sonno che non veniva e sfogliando il catalogo di una mostra sugli Oceani, sottratto al mio figlio adolescente, che sono capitato, o piuttosto ricapitato, su certune incisioni antiche di mostri marini.

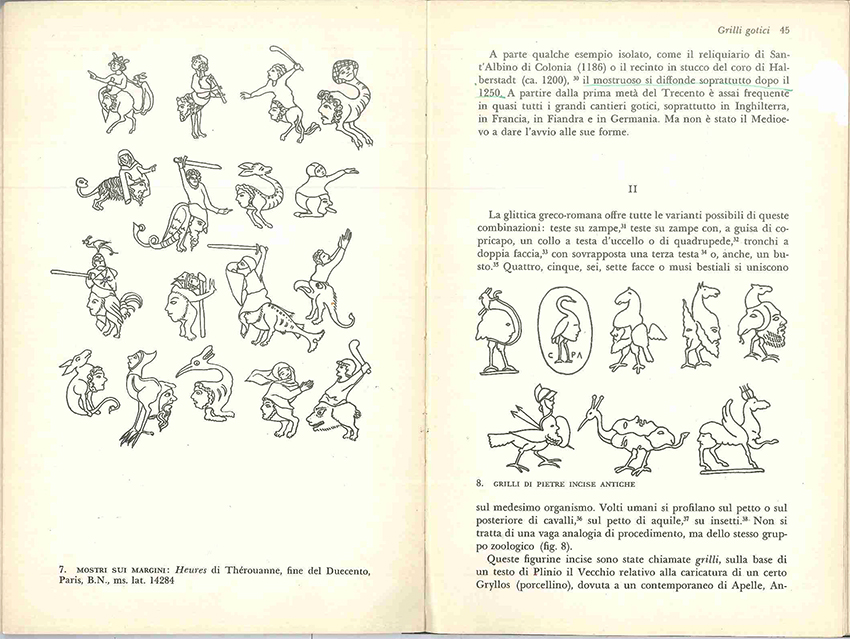

Occorre dire che il mio cervello stava in una qualche attesa o ricerca di immagini più o meno subliminali ma comunque favorevoli all’incubo, poiché altri due libri erano poggiati sul comodino: Monstros, del filosofo portoghese José Gil (Lisboa 1994) e Metamorfosi di Emanuele Coccia (Torino 2022).

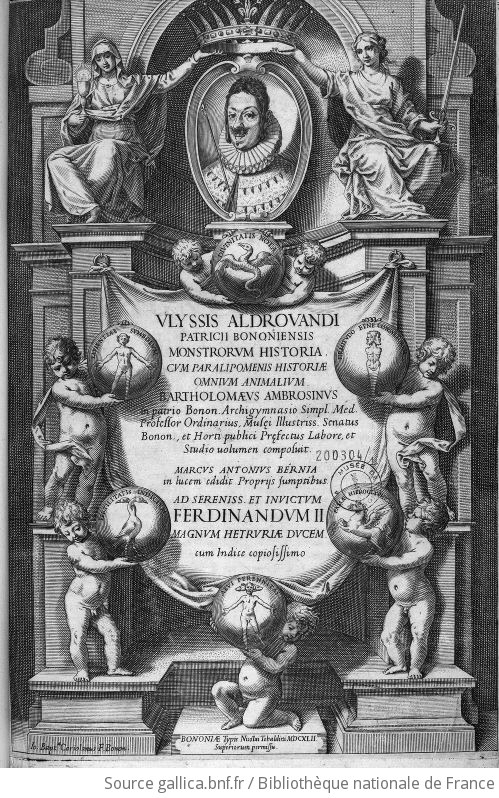

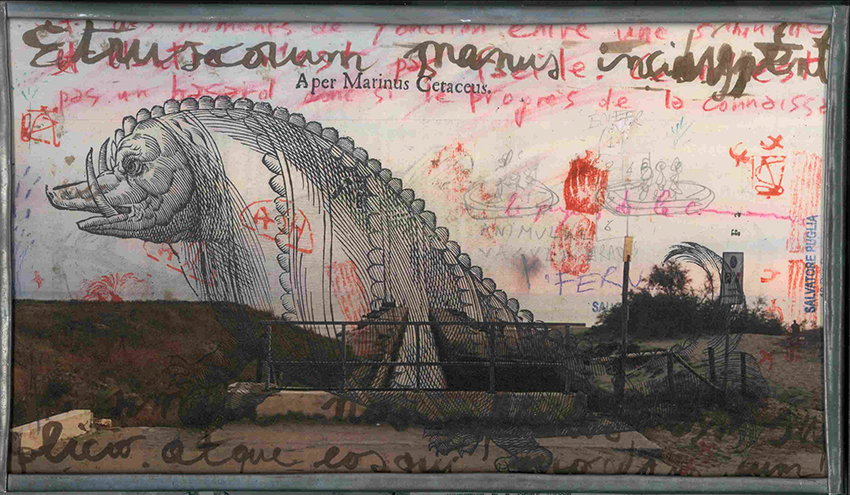

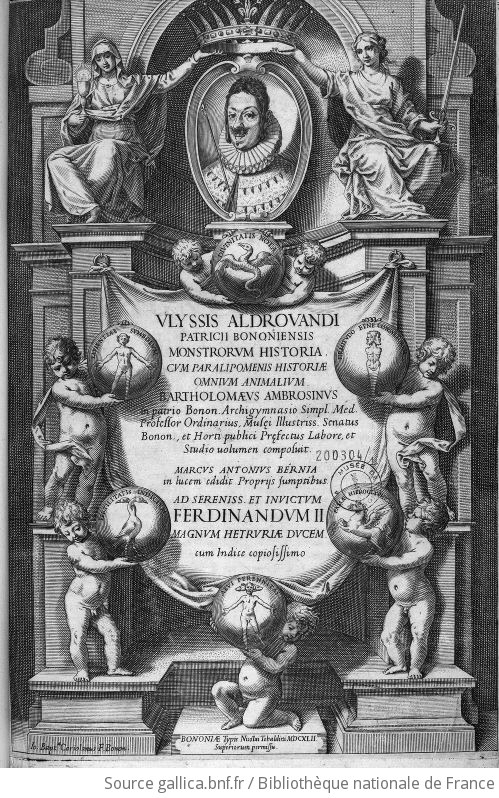

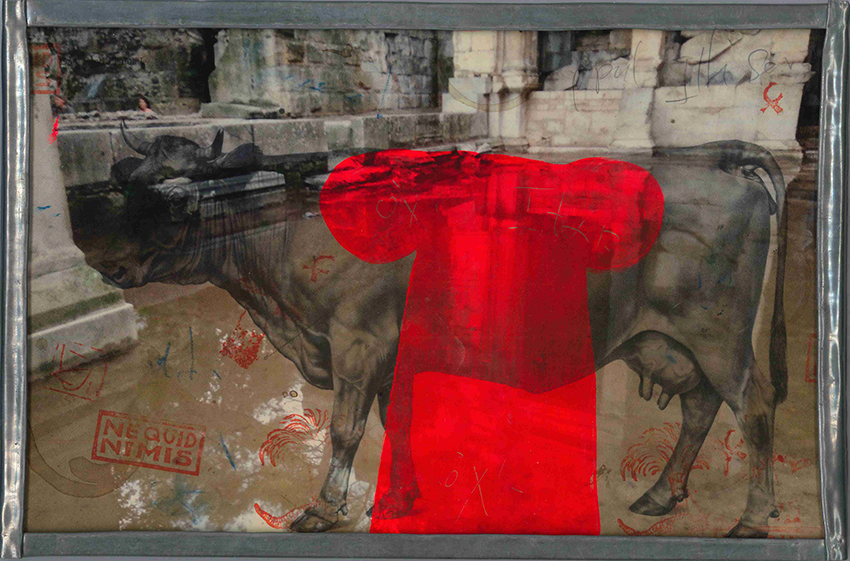

L’indomani della mia riscoperta ho cercato in biblioteca un’edizione dei bestiari di Ulisse Aldrovandi (1522-1605), il medico e filosofo bolognese unanimemente considerato un precursore degli studi di storia naturale. Sono capitato (ad libitum), nella modesta biblioteca municipale di Nîmes, su una prima edizione del Monstrorum Historia. Pubblicato a Bologna nel 1642, l’esemplare che avevo fra le mani portava la firma del priore della Certosa di Villeneuve-lès-Avignon: “Emptus Anno 1643”, acquistato nel 1643. Era evidente che, in seguito alle espropriazioni dei beni ecclesiastici successive alla Rivoluzione francese, la biblioteca della certosa, o almeno una sua parte, si era ritrovata nel capoluogo regionale.

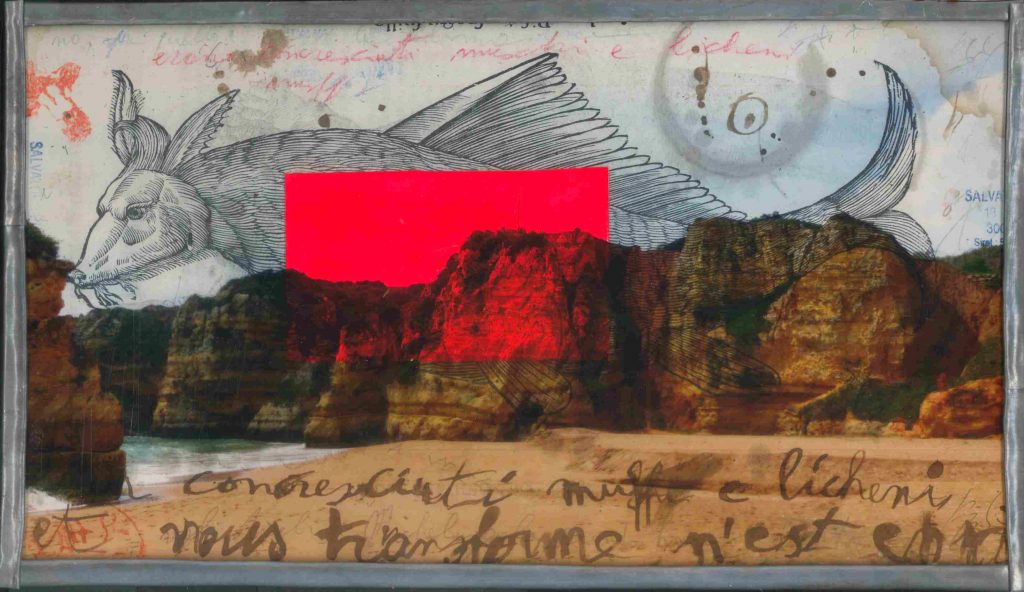

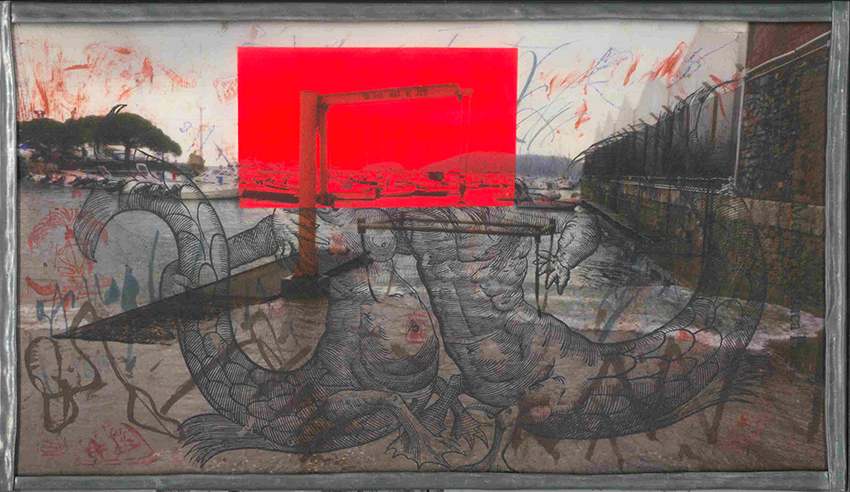

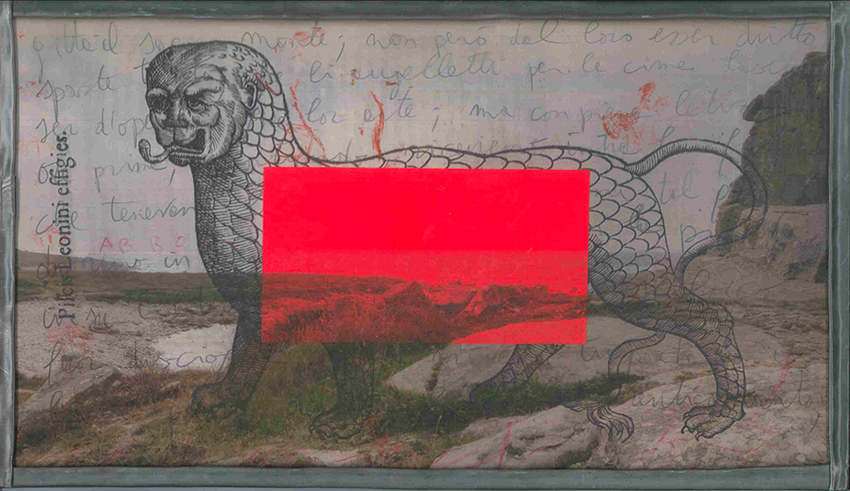

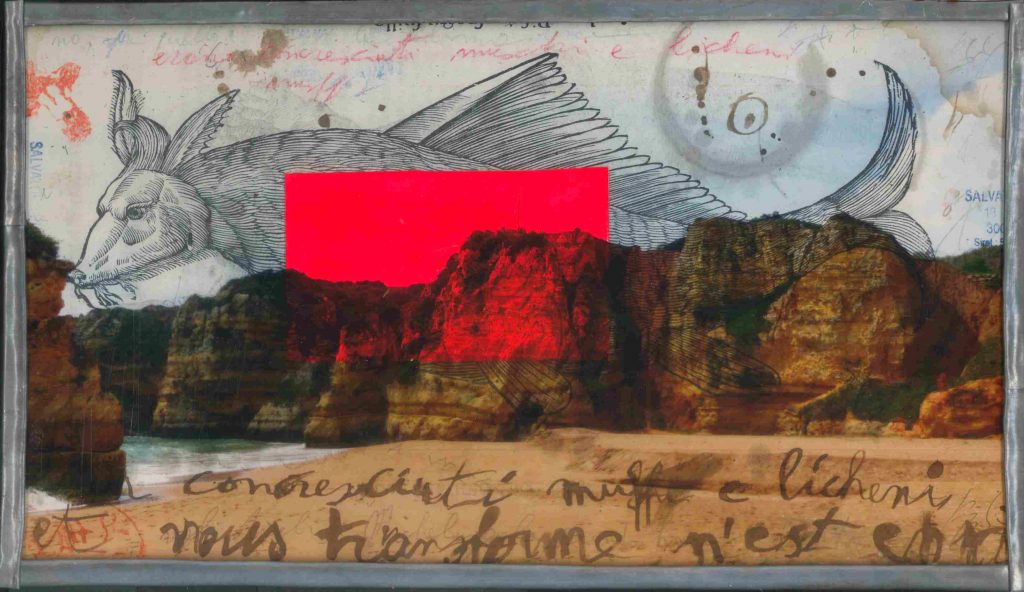

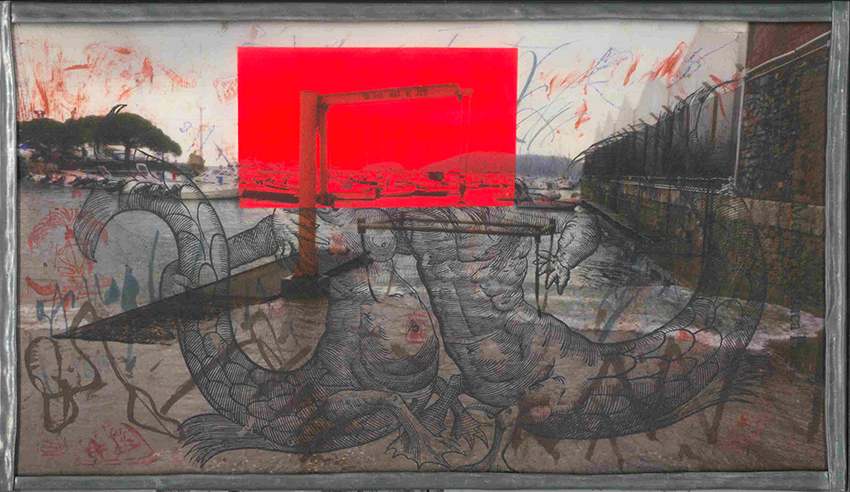

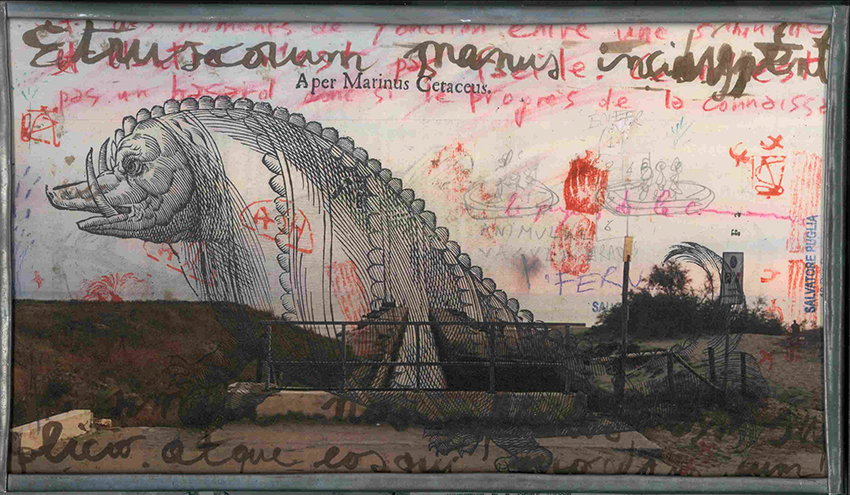

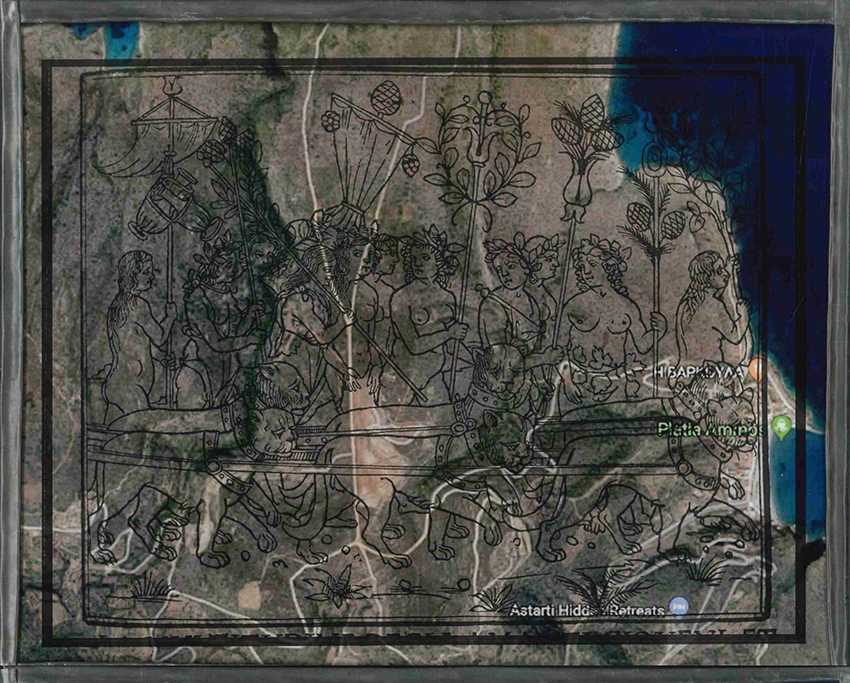

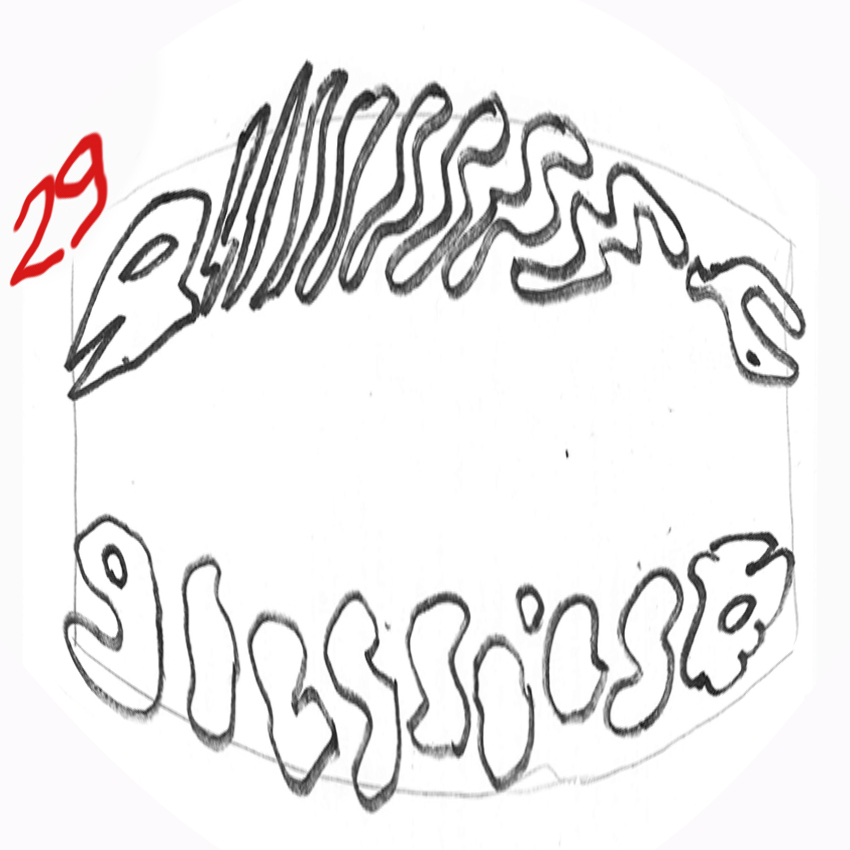

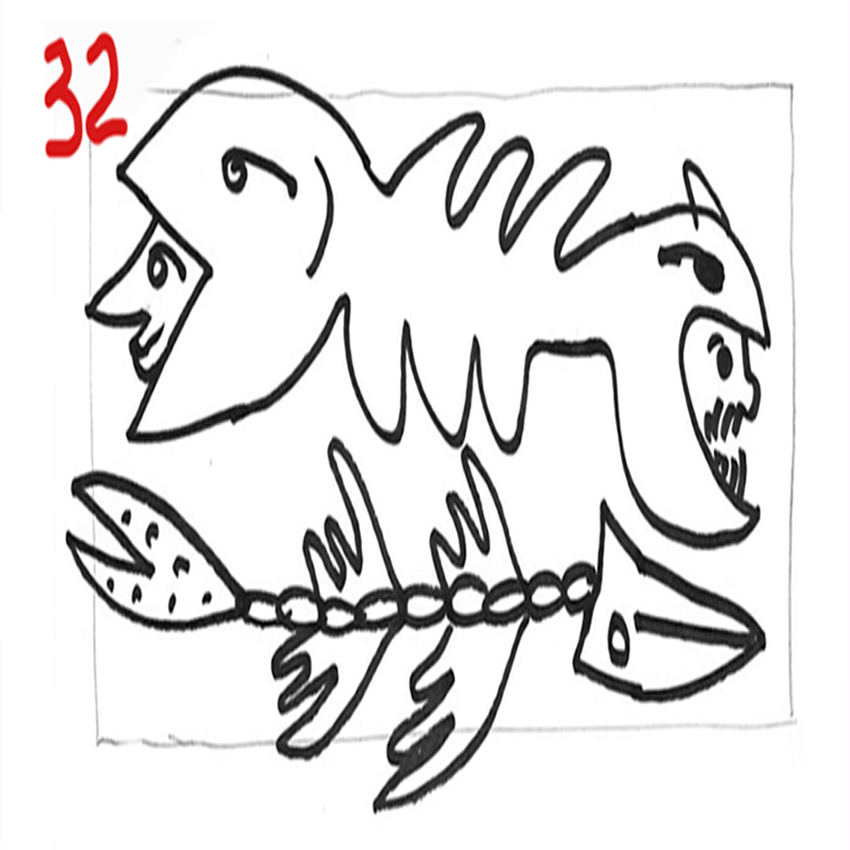

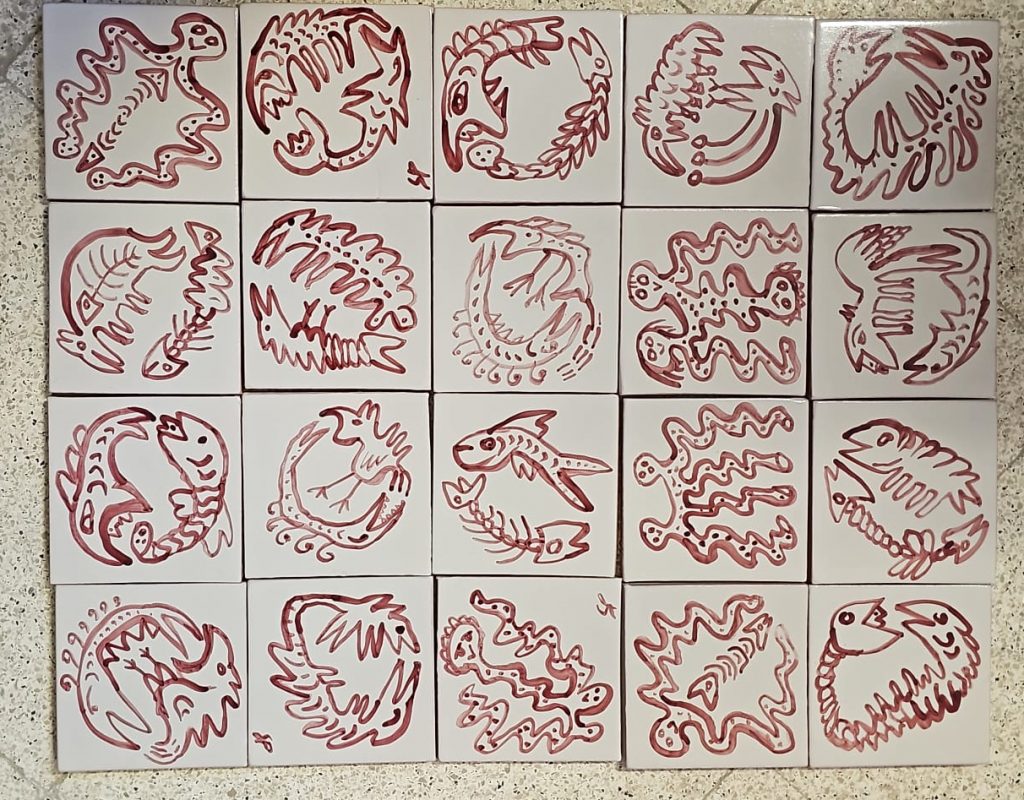

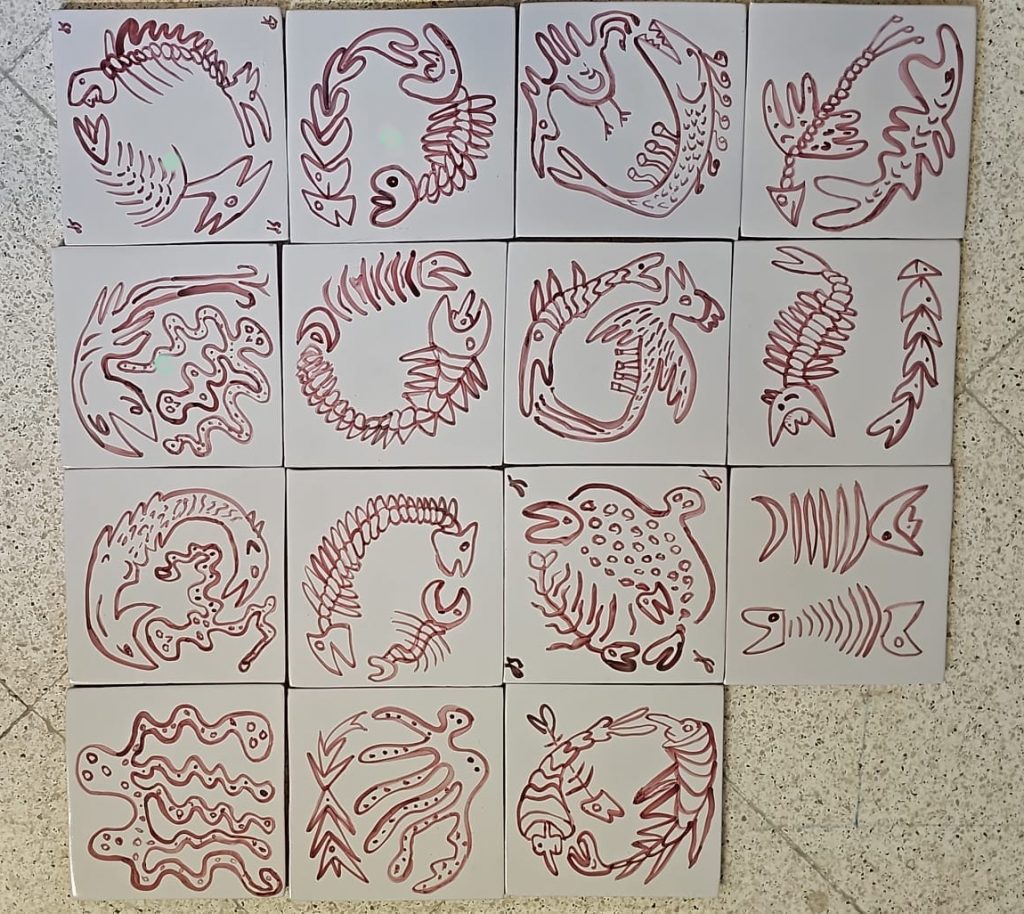

Fra tutte le creature mostruose repertoriate dall’Aldrovandi (raramente per diretta osservazione) ho scelto gli animali marini. Mi sono parsi più atti ad adattarsi agli habitat visivi che ho loro imposto in modo tirannico.

Questa serie presenta quindi in tela di fondo la riproduzione d’una incisione aldrovandiana, sulla quale una fotografia di paesaggio, riprodotta su vetro, è posata. Sono presenti anche elementi testuali, che non hanno relazione analogica con uno strato o con l’altro, ma costituiscono la cucitura che li rilega fra loro, come marginalia apposti nel corso della lettura. Sono citazioni dai testi che hanno accompagnato il mio lavoro, trascritti all’inchiostro di china o al pastello a cera, a volte sottolineati da timbri cineseggianti (oltre ai citati Gil e Coccia: Jurgis Baltrusaitis, Le moyen âge fantastique, Paris 1955, Gilbert Lascault, Le Monstre Dans l’Art Occidental, Paris 1973, Claude Kappler, Monstres, démons et merveilles à la fin du Moyen Age, Paris 1980 e Martial Guédron, Les monstres, Paris 2018).

.

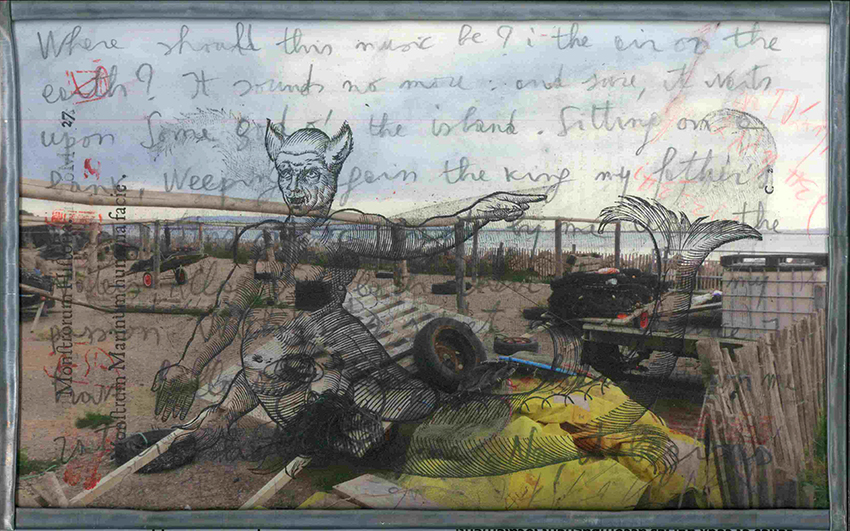

Dicembre 2023.

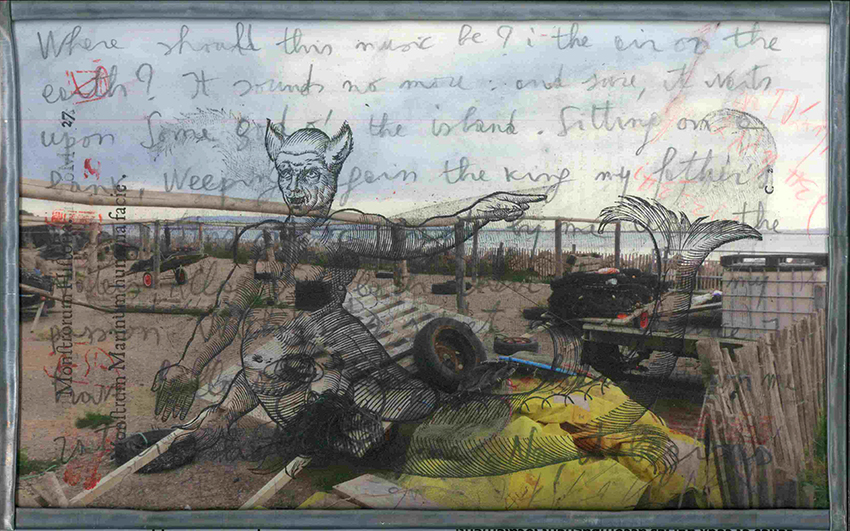

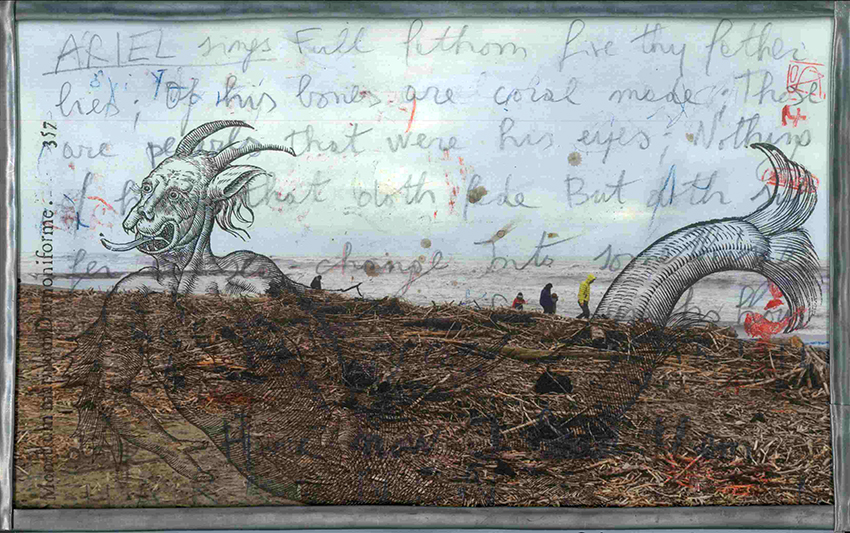

Ciò che mi sembra essere cambiato radicalmente nel mondo occidentale negli ultimi decenni – in modo sempre più accelerato – e che mette in minoranza tutti i principi dell’Illuminismo, dell’umanesimo secolare e persino dell’umanesimo cristiano, è la concezione dell’“altro”. È come una cristallizzazione dello straniero, percepito come un blocco di estraneità e pericolo e, ovviamente, considerato meno umano di “noi”.

Il tema dell’alterità mi ha sempre interessato, forse per ragioni autobiografiche, così come quello dell’intruso, colui che si trova nel posto sbagliato al momento sbagliato.

Nel realizzare quadri in cui raffiguro mostri marini che approdano sulle rive del Mediterraneo mi chiedo chi sia più mostruoso, questi pesci o questi anfibi dal volto umanizzato, o coloro che li lasciano agonizzare sulle spiagge. Mi interrogavo sulla parte mostruosa dell’uomo occidentale.

Questa serie fa anche eco ai cambiamenti politici e sociali che stiamo vivendo. I “miei” mostri sono allegorici, certo, e hanno quel lato ‘umano’ che può ispirare simpatia: pur essendo paria, “alieni”, sembra che si possa parlare con loro una stessa lingua. Ci si chiede se non si possa essere amici.

Questa serie mi ha tenuto occupato per quasi tre anni ed è stata la mia unica attività creativa, oltre alle mie produzioni di arte applicata. Nell’inverno 2024-2025 ho ancora percorso in auto le coste del “Mare di Mezzo”, da Port Bou a Vietri sul Mare, a sud di Napoli.

Questa serie mi ha tenuto occupato per quasi tre anni ed è stata la mia unica attività creativa, oltre alle mie produzioni di arte applicata. Nell’inverno 2024-2025 ho ancora percorso in auto le coste del “Mare di Mezzo”, da Port Bou a Vietri sul Mare, a sud di Napoli.

Ho fotografato luoghi che già conoscevo sotto la luce estiva. L’aspetto di queste coste è molto diverso in inverno. Sono trasformate dalle tempeste autunnali, con tutti i detriti e i relitti che le ricoprono e che vengono ripuliti con l’avvicinarsi della bella stagione.

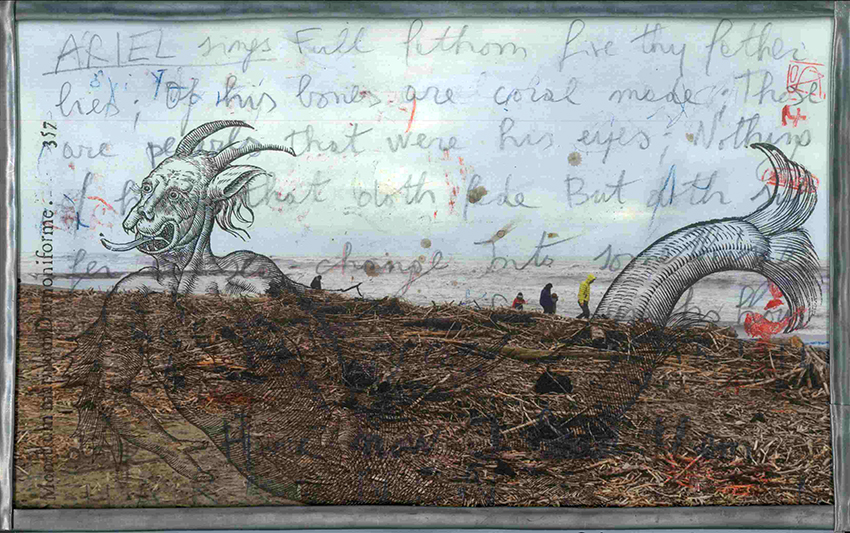

Ho trascritto vari testi sulle incisioni aldrovandiane, in modo frettoloso e approssimativo: brani della Tempesta di William Shakespeare, quelli della canzone di Ariel (Full fathom five thy father lies;/ Of his bones are coral made; Those are pearls that were his eyes: Nothing of him that doth fade, But doth suffer a sea-change/ Into something rich and strange).

(2021-2025, Histoire des monstres suite)

(2021-2025, Histoire des monstres suite)

.

Ho anche copiato a matita la meravigliosa traduzione napoletana della canzone di Ariel, scritta da Eduardo De Filippo poco prima della sua morte e pubblicata da Einaudi nel 1984: Nfunn’a lu mare/ giace lu pate tujo./ L’ossa so’ addeventate de curallo,/ ll’uocchie so’/ dduje smeralde…/ E li spoglie murtale, tutte nzieme/ se songo trasfurmate:/ mò è na statula de màrmole/ prigiato, sculpito e cesellato!

* Hannah Arendt, ”Walter Benjamin, L’omino gobbo e il pescatore di perle”, Il futuro alle spalle, Bologna 1981, p. 160.

.

Hopi a Poggio Rota, 2017, 20×30.

Hopi a Poggio Rota, 2017, 20×30. Baedeker-Roja 01, 2018, 20×30.

Baedeker-Roja 01, 2018, 20×30. Regordane 01, 2019, 20×30 (from the installation Millenovecento). See the remaining pieces : Millenovecento residui.

Regordane 01, 2019, 20×30 (from the installation Millenovecento). See the remaining pieces : Millenovecento residui. Baedeker-Roja 02 bis, 2023, 20×30.

Baedeker-Roja 02 bis, 2023, 20×30. Senza titolo (diploma), 2025, 20×30.

Senza titolo (diploma), 2025, 20×30. Nella selva antica 08, 2025, 20×30.

Nella selva antica 08, 2025, 20×30. Paulhan 02bis, 24×36 (a 2022 revisited piece).

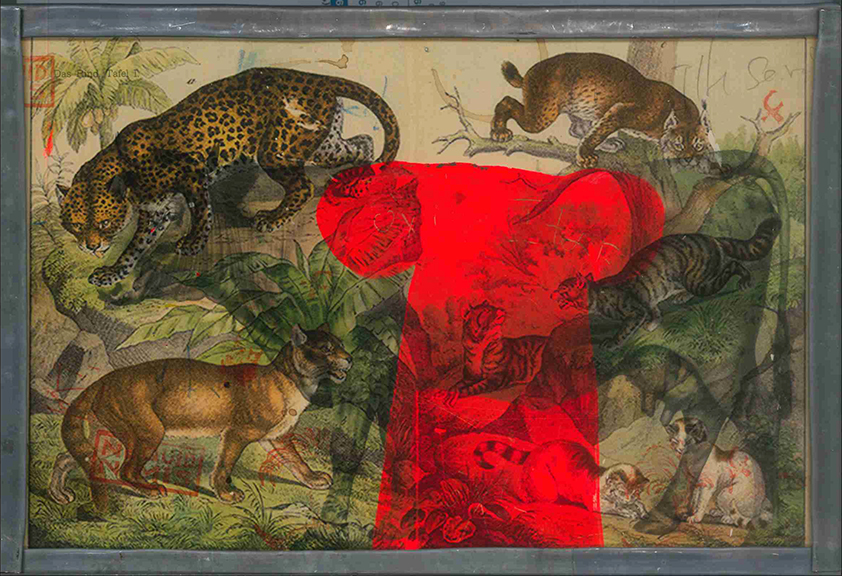

Paulhan 02bis, 24×36 (a 2022 revisited piece). Raubtiere-Das Rinde, 20×30, 2025.

Raubtiere-Das Rinde, 20×30, 2025. Gulliver in Tuscia, diptych, 30×10, 2025 (private collection).

Gulliver in Tuscia, diptych, 30×10, 2025 (private collection). Au Temple de Diane 02 bis, 20×30, 2025 (a 2020 reworked piece).

Au Temple de Diane 02 bis, 20×30, 2025 (a 2020 reworked piece). Ordinary Humans 04 E, 20×30, 2026 (a 2019 reworked piece).

Ordinary Humans 04 E, 20×30, 2026 (a 2019 reworked piece). Ordinary Humans 06, 20×30, 2026 (a 2019 reworked piece).

Ordinary Humans 06, 20×30, 2026 (a 2019 reworked piece). Mediterraneo, 10×20, 2026 (from the series Millenovecento).

Mediterraneo, 10×20, 2026 (from the series Millenovecento).

Histoire des monstres 07 bis, Via cava Fratenuti-Raia exiccata, 24×42.

Histoire des monstres 07 bis, Via cava Fratenuti-Raia exiccata, 24×42.

Histoire des monstres 16 bis , Maguelone-Monstrosus Cyprinus, 24×42.

Histoire des monstres 16 bis , Maguelone-Monstrosus Cyprinus, 24×42. Histoire des monstres 02 bis, Lagos-Andura piscis, 24×42.

Histoire des monstres 02 bis, Lagos-Andura piscis, 24×42. Histoire des monstres 11 ter, Camp de César-Niliaca Parei, 24×42.

Histoire des monstres 11 ter, Camp de César-Niliaca Parei, 24×42.

Les monstres du Gardon 01, 24×42, 2023.

Les monstres du Gardon 01, 24×42, 2023. Les monstres du Gardon 02, 24×42, 2023.

Les monstres du Gardon 02, 24×42, 2023. Paulhan 00, 24×36, 2023. La série de six :

Paulhan 00, 24×36, 2023. La série de six :  Nuovi mostri 01, 30×42, 2023.

Nuovi mostri 01, 30×42, 2023. Le monstre du Gardon, 20×30, 2023.

Le monstre du Gardon, 20×30, 2023. Garriga-Potlatch, 30×30, 2023.

Garriga-Potlatch, 30×30, 2023. From the Road 02 bis (Nages), 31×50, 2023.

From the Road 02 bis (Nages), 31×50, 2023. From the Road 01 bis (Camp de César), 31×50, 2023.

From the Road 01 bis (Camp de César), 31×50, 2023. Ponge 06, 24×42, 2022. La série de six :

Ponge 06, 24×42, 2022. La série de six :  Menard 05, 28×42, 2022. La série de six :

Menard 05, 28×42, 2022. La série de six :  Feuchtwanger 01, 30×40, 2022. La série de sept :

Feuchtwanger 01, 30×40, 2022. La série de sept :  Histoire des monstres 11 (Laudun l’Ardoise), 24×42, 2021.

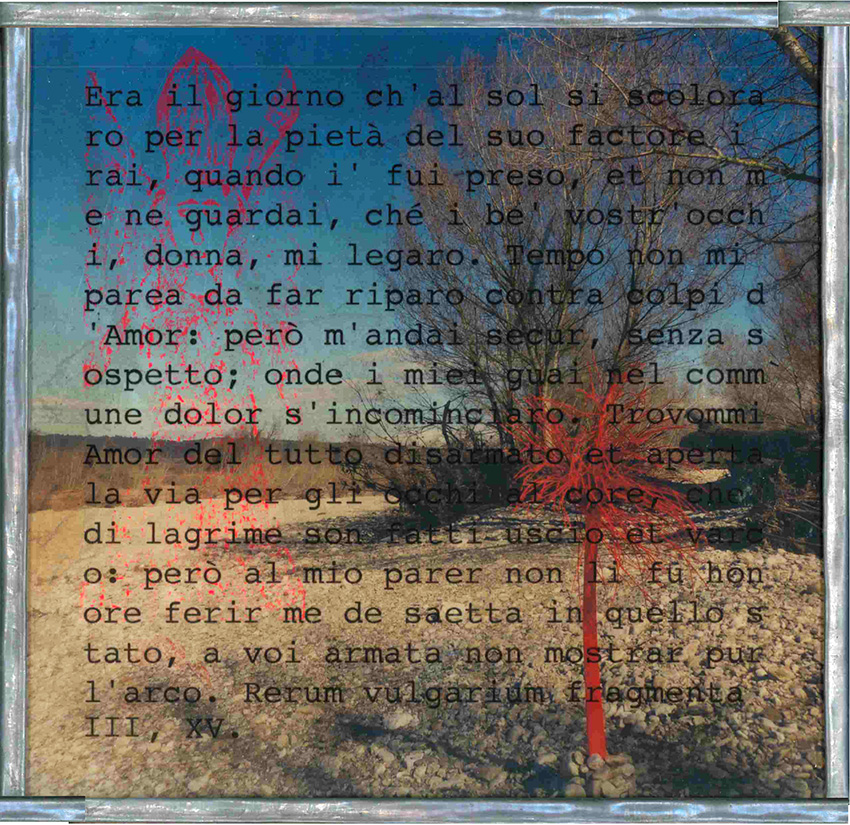

Histoire des monstres 11 (Laudun l’Ardoise), 24×42, 2021. Garriga-Petrarca III, 32×32, 2021.

Garriga-Petrarca III, 32×32, 2021. Au Temple de Diane 02, 20×30, 2020.

Au Temple de Diane 02, 20×30, 2020. Ordinary Humans 10, 20×30, 2019.

Ordinary Humans 10, 20×30, 2019. Ordinary Humans 01, 20×30, 2019.

Ordinary Humans 01, 20×30, 2019. Nella garriga 08, 45×60, 2017.

Nella garriga 08, 45×60, 2017.