On Painting as Translation

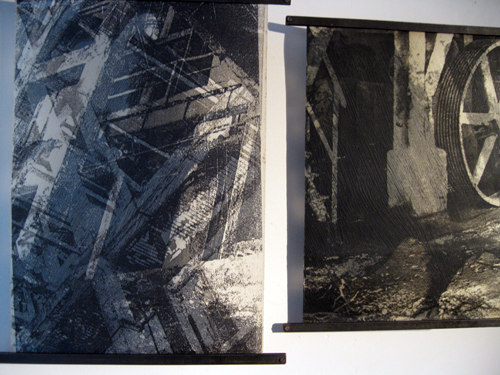

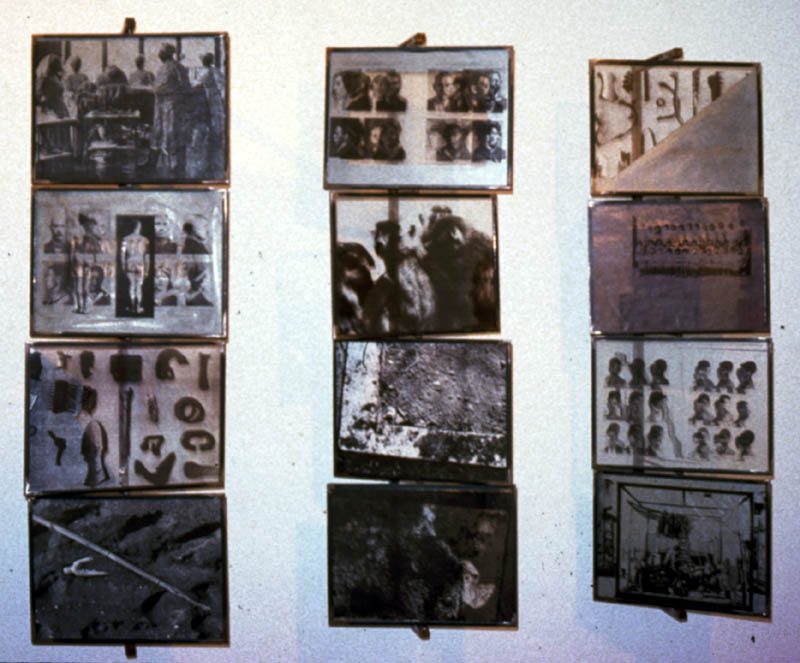

The stories that I am going to lay out are not meant to constitute a whole picture or organic tableau. On the contrary, my stories will be disjointed ; they will be examples, sometimes oblique examples, of a discourse on the way in which certain literary texts can exercise their influence on a person’s attempts to practice, or practice in, the visual arts. These stories, I present them to you as splinters of experience and as fragments of a reflection that has marked the work that I will show you after my short talk. I hope that the processing of images that you will see will be like the thread sewing together the scattered moments of this experience.

I will discuss four topics :

1. Stendhal’s Pictograms

2. Artaud’s Cryptograms

3. Bataille´s Photograms

4. Benjamin’s Topograms

Stendhal’s pictograms

I want to say words about Henri Beyle, who used the name Stendhal, or Henry Brulard, and about the circumstances that led him to write the story of his life.

In the morning of October 16, 1832, Henri Beyle (who was, then, French Consul in the coastal town of Civitavecchia in the Papal States) found himself in Rome on the Janiculum Hill in front of the church San Pietro in Montorio. Instead of putting my words in his mouth, I will quote the very first lines of his book, the Life of Henry Brulard.

I was standing this morning, October sixteenth, eighteen thirty-two, by San Pietro in Montorio, on the Janiculum Hill in Rome, in magnificent sunshine. A few small clouds, borne on a barely perceptible sirocco wind, were floating above Monte Albano, a delicious warmth filled the air and I was happy to be alive.

All of Rome, both ancient and modern, unfolds under Stendhal’s eyes from this location, the square before the church, which forms a terrace overlooking the city, which is a place unique in the world, where Raphael’s Transfiguration had been the object of admiration during two and a half centuries, or two hundred and fifty years.

Ah! (Stendhal writes) in three months I shall be fifty; can that really be so ! Seventeen eighty-three (1783), ninety-three (’93), eighteen hundred and three (1803) — I’m reckoning on my fingers – and eighteen thirty-three (1833) make fifty. Is it really possible ? Fifty !

This unexpected discovery did not vex me ; He says I had been thinking about Hannibal and the Romans.

In Stendhal’s reconstruction in words, there is a double layering or stratification of reflection and memory. Under his eyes lies Rome: like an open archaeological excavation site, it exhibits history’s layers one on top of the other, from antiquity until now, when Stendhal beholds it. These are the first layers or strata; the second set of strata or layers consists of the movement of time coming toward him, all of time leading up to this October 16, 1832. Stendhal notices that Raphael’s painting have hung there for two hundred and fifty years, that is to say five times fifty; he remarks: “and I am fifty years old !”.

“I shall soon be fifty, it’s high time I got to know myself. I should really find it very hard to say what I have been and what I am”.

The project he undertakes is devoted to establishing a line of continuity. A continuity of self-knowledge, but also a continuity in relation to a future reader, the intelligent interlocutor Stendhal lacks in his present.

You can see a straight line in the time scheme (from Hannibal and the Romans all the way to the future reader), but this line breaks at some point. This point is a moment when the pleasure of anamnesis, the pleasure of bringing in and bringing up the past, is the strongest, and this is when an exclusive and strong connection is made between the act of remembering and the actual past. This is a point in time when something unusual happens.

In a text, such as the one from which I have been risking, that is remarkable already because there is such a short distance between itself and its object, it seems as if even this small gap automatically created by the writing gesture has become unbearable, insufferable. There thus comes a moment when one must look for, and find, a better way to immerse oneself in the past, or literally to bring the past toward oneself. This is a need, and it requires another means, different from the alphabetic one, of making inscriptions. We are going to see exactly how Stendhal is moving to a different graphic medium.

He recalls his ancient loves and feels an urge to trace on a dusty trail the names or initials of the women he loved. He takes a walk on a solitary trail overlooking Lake Albano, he stops and, with his walking stick, writes those initials on the ground, in the dust, “as did Zadig,” he notes. Later he tackles the Life of Henry Brulard again.

(Here I should at least allude to the layering of the various names, and how in Stendhal there is no identity or identification without this disguise of names or pseudonyms.)

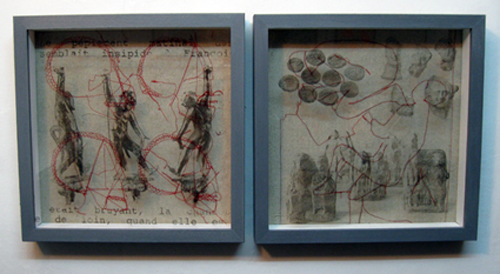

As he resumes writing Henry Brulard, he thinks again about the women he has loved and he thinks about himself in the act of writing their names in the dusty trail. And now, suddenly, he switches media: he interrupts the written manuscript with a sketch. The sketch of himself, on the trail by Lake Albano, in the act of tracing women’s names on the dusty ground.

From that moment on, and each time something particular in his work of rememoration triggers an emotion (it could also be an intense pleasure, naturally), he replaces the description in words with one in images. In this way now, his manuscript is interrupted on almost every page, is stuffed with sketches, maps, figures with legends, or abbreviations that lead to notes of explanation.

I can summarise where the drawing fits in, in the book, by saying that the drawings complete or replace the writing in words with another writing that one can perceive as more precise, more immediate and truer, perhaps more efficient when it comes to reconstituting or resurrecting the past, to reducing the distance from himself.

I can’t help but wonder what method or means Stendhal would have chosen if, instead of writing his life just a few years before the official invention of photography, he had found himself delving in his past and beholding Rome at the same time, at a moment when cameras were available. In any case he probably would have turned into a passionate amateur photographer, given his obsession with precise recalling. (He said: “I cannot render facts in their reality; I can only give their shadows”). It occurs to him that memory deals with fragments; he says: “Next to the brightest faces, I find missing parts in my memory, like a fresco from which large sections have dropped away.”

Whatever the case may be, I am confident that Stendhal would have still done his sketches and drawings, what we can call his pictograms, which come to his emotional rescue.

Artaud’s cryptograms

Let us step back a little bit and suppose that instead of using a language that describes things while keeping at a safe and steady distance from those things, one handled words that resemble the objects in question or the circumstances they aim to express; that we had a “resembling” language that was disjointed, that precede syntax; that the words pronounced did barely more than dress things up, the written words remaining barely shaped and still isolated from one another. Such a language that does not distance itself from things, which is a language of the guts, both a particular and a universal language, was the one employed by Antonin Artaud.

For years I have had an idea of the consumption, the internal consummation of language by the unearthing of all manner of torpid and filthy necessity. And, in nineteen thirty-four, I wrote a whole book with this intention, in a language which was not French but which everyone in the world could read, no matter what their nationality. (From Artaud’s Letter to Henri Parisot).

Among many other texts, I should refer to Artaud’s text on Van Gogh, and to its organic, volcanic, intolerably passionate language, to its untiring and breathless rhythm.

Antonin Artaud wrote this text on Van Gogh in 1947, after he saw a large Van Gogh exhibition in Paris. His title is Van Gogh, The Man Suicided by Society. Here, as in Stendhal, there is a remarkable passage, a sort of jump both in the emotions and in the language, a jump resulting from the identifying character of these writings. In Artaud’s text, the reader passes several times and quite suddenly from a regular sentence to a sort of encoded sound or cryptogram.

It is literally true that I saw the face of Van Gogh, red with blood in the explosion of his landscapes, coming toward me

Kohan

taver

tensur

purtan

in a conflagration

in a bombardment

in an explosion

These expressions really have no meaning; they simply evoke something that comes from elsewhere and an ancient time, something from time immemorial. Here the reader finds him -or herself- grappling with questions surrounding the origin of language or rather, to be more precise, with the tension towards an origin.

Empedocles, in one of his fragments, places man’s birth in a sort of generalised disjointed state :

On it (the earth), many heads sprung up without necks and arms wandered bare and bereft of shoulders. Eyes wandered up and down in want of foreheads. (Fragment 57)

Solitary limbs wandered seeking for union. (Fragment 58)

These are, then, organs that are lost, gone astray, trying to unite with a body or to find a body that would link them in one way or another. This actually foreshadows Georges Bataille and his “disorder of the human body, work of a violent disagreement of its organs” (“Le gros orteil,” in Documents 1929).

Often artists feel that their paintings are like bodies with which they need to wrestle, in face-to-face confrontations, and there is no telling who will win the fight. Let us try to imagine such a fight against such a body as Empedocles describes it, a body that is not a body, a body, dislocated, exploded, an organic entity yet disorganised and incoherent.

Shambling creatures with countless hands. (Fragments 60)

Clearly there can be no face-to-face encounter or fight with such an entity, nonetheless it is

necessary and cannot be avoided. Let us consider the artist and the painting as body and soul, as Aristotle depicts them in his text on Etruscan torture. Cicero reports that Aristotle stated that man’s condition is as follow:

We live through tortures like the ones suffered by those who, in an earlier time, were killed in a very refined manner by Etruscan pirates who captured them: the live bodies of prisoners were tied very precisely to the bodies of dead ones in such a way that the front part of each living one was fit to the front of a dead one. That is how these living ones were linked to the dead ones as our souls are tightly linked to our bodies.

I imagine that one of these inseparable parts is the shadow. The shadow could be the memory; indeed, memory holds us tightly, it keeps us from becoming severed from ourselves ; it ties us to our own history in a loyal, sometimes too loyal, relationship to our identity: “he who cannot forget will achieve nothing”, said Kierkegaard.

Georges Bataille’s photograms

If we speak of bodies and signs, we speak of anatomy, we speak of the body opening to allow the retrieval of signs. These signs can speak of themselves or they can speak of the body that contains them, but above all these can, for the anatomist, speak of other bodies. Therefore such signs will make it possible to open up to the experience of other bodies and other things.

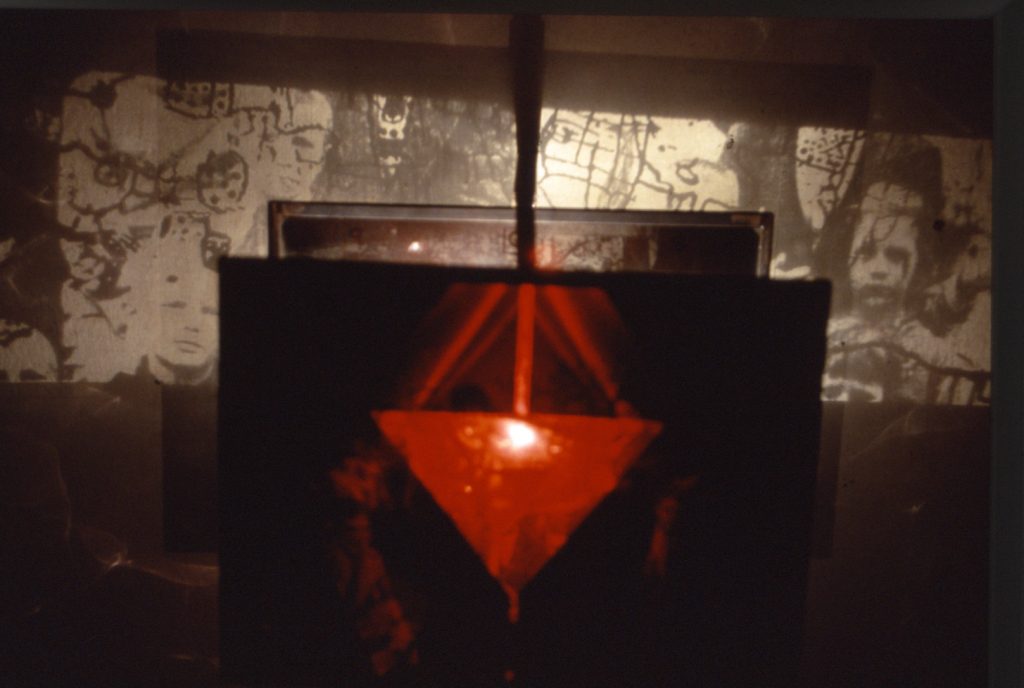

I have mentioned body organs, torture, severed limbs, and cut-up tongues. This brings to mind the most intense photographic picture, next to which any other photographic image becomes an act of torture because of its kinship with this particular image. I am speaking of the Chinese torture image, that appears in Bataille’s book The Tears of Eros (1961).

“Since 1925”, Bataille says, “I have owned one of these pictures. It was given to me by Doctor Borel, one of the first French psychoanalysts. This photograph had a decisive role in my life. I have never stopped being obsessed by this image of pain, at once ecstatic and intolerable”.

Bataille in fact presents four images in a row. A fifth one exists, which is the last one and the most terrifying ; Bataille did not include it in his book. These images were readily available and could be bought as stereograms, with the brand name Veroscope. The word “veroscope” points to the trustworthiness of the three-dimensional, stereoscopic images in their capacity to restore the presence of the thing.

It is well known that Bataille is interested in the ravished and ecstatic expression of the young Chinese man who is being tortured. Bataille says also, however, that the young man’s expression could be caused by a large dose of opium given to this patient who is being subjected to a live anatomical dissection.

The point here is that Bataille is interpreting physiognomy instead of taking the photo as the simple capture of a moment of affective violence.

I will come back to the question of physiognomy in a moment. For now, I want to discuss the parallel I make between the anatomy of language and the language of the body. Let me tell a bit more on what I am calling “somatograms”.

The gesture that consists in copying, in transcribing, in reproducing is most closely related to the work of interpreting or translating of which it constitutes the sine qua non.

The technical reproduction of the inside of the human body is, of course, known as radiography or X-ray photography (not to mention more recent imaging and scanning techniques). X-ray imaging makes use of the principles of photography (by making an image on a chemically treated plate) and the principles of radioactivity (by penetrating the resistance, that is to say the unity of bodies, with rays).

Therefore radiography is a photocopy of what is hidden ; it is a “radiocopy”.

The spectral image we see offers alternate patterns of shade and light. This image possesses the characteristics of a double and a negative; it constitutes a kind of representation of the aura (I will speak imminently of the “aura” in Walter Benjamin’s writing), or, if you prefer, this image is a soul-guard of the body, or a bodyguard of the soul.

I just want to quote briefly a well-known text, which is very evocative in this context. Is Kafka’s comment on photography, in which he seems to oppose interior vision and bird’s-eye vision:

Photography concentrates one’s eye on the superficial. For that reason it obscures the hidden life which glimmers through the outlines of things like a play of light and shade. One can’t catch that even with the sharpest lens. One has to grope for it by feeling… This automatic camera doesn’t multiply men’s eyes but only gives a fantastically simplified fly’s-eye view.

Walter Benjamin’s topograms

In speaking of reproduction, I want to push further the metaphoric relation between written text and bodily texture. This leads me to Walter Benjamin, the famous German critic and philosopher.

In his books, he comes back several times to questions having to do with copying, transcribing texts manually. There is one such passage, for example, in which he tells of having to stay in school and copy texts as punishment (in Berliner Kindheit, written toward the end of the Thirties; the passage is entitled Strafe des Nachsitzens). Elsewhere he compares the reader’s activity with that of a scribe or transcriber: the former is like a passenger in an aeroplane who would decipher a landscape that he sees as a whole, in its entirety, but without seeing the ups and the downs, the roughness, the unevenness, while the latter would be like the driver of an automobile, well aware of the roughness of the terrain, who would travel through the same landscape.

In these images given by Benjamin, there is a sort of truth of contact, of slowness, whether the transcribing is done voluntarily or not. Can there be any greater fidelity to the text than to walk and proceed through it step by step by transcribing it letter by letter?

(Remember now Stendhal’s fidelity or loyalty to his memory, his ancient loves, his names and the names of his women, and think of the mapping out, the topograms resulting from this; think of the topographical image of written reproduction found in Benjamin; think also of the structure of Benjamin’s work, Einbahnstrasse (One-way Street), of 1928).

To reproduce is to repeat. Photography, like memory, reproduces, reproduces itself, and repeats itself. The illusion that one relives something comes with repetition. One is fooled by a reality of which there is a photographic double.

There is a text on photography by Georges Bataille. It was published in the journal Documents in 1929 and it was called Figure humaine, “The Human Figure”. As he comments one of the most banal pictures that exists, that is to say a group photograph taken at a wedding somewhere in France in 1905, Bataille attacks the paltry and misleading nature of photographic portraits in general.

Photography is too easy, he implies.

Now, unlike in other places and times, and because of photography, we have stopped being haunted by spectres or ghosts who, having “the miserable aspect of half-decomposed bodies,” might be feared as man-eaters. Photography proposes us, instead, a laughable ersatz of our spectres.

Photography covers and dresses wounds, it mitigates, it takes the edge off things, it consoles, it claims to preserve. It is guilty since it furnishes us with a small and misleading part of reality. Photography feeds the illusion that we are in touch with what has been, while masking the actual truth of what has preceded us, namely the dissolution and disappearance of things, and cancelling instants themselves by its own instantaneous action, cancels our right to the instant to the unknown.

Bataille’s critique of photography is close to Kafka’s; photography does not leave us in peace with our own spectres.

I quote Bataille again:“The very fact that one is haunted by such benign apparitions gives fear and anger a pathetic or laughable value”.

It is the pretension to truth-telling itself that Bataille is aiming at here.

Bataille attacks photography’s pretence to reach the truth. The human figure reproduced by photographic means claims to reconstitute a human nature.

To such a pretence, Bataille opposes, I quote, “a presence as irreducible as that of the ego.”

I want to simplify things a little here and say that we are dealing here with a criminality of photography, which consists in endangering the individual; it is, though, a crime of lèse-individualité.

Bataille is not far from the views that stretch from Baudelaire to Valéry and others, and which underscore essentially the documentary role of this means of technical reproduction, photography, in opposition to the subjective freedom on which rests the work of art. Bataille sees photography as participating fully in the movement that began in the early years of the nineteenth century, the movement that strove to recover (and recognise?) the human figure by any means.

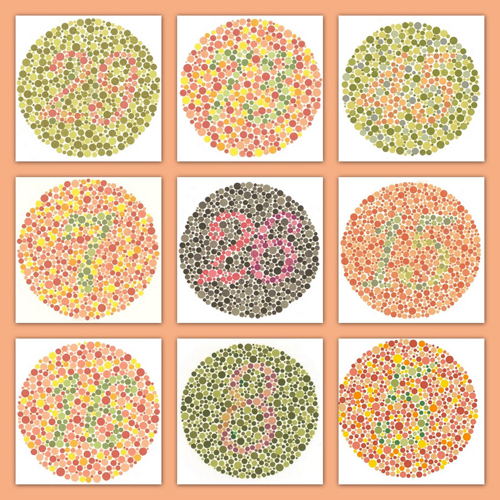

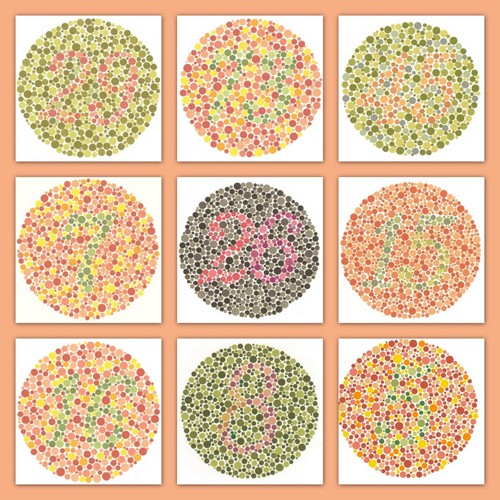

Photography is the expression of an “intellectual voracity,” which goes from Lavater’s work in physiognomy (in the second half of the eighteenth century) to Gall’s phrenology, Broca’s craniology, and Lombroso’s criminal anthropology, followed by Charcot’s photographic iconography, as well as Bertillon’s metric anthropology, all the way (perhaps a little arbitrarily) to a number of scientific publications, such as (I translate the French titles):

Nineteen Visible Physical Defects to Recognise a Jew, published in Paris in 1903, and How to Recognise and Explain a Jew : With Ten Plates, Followed by a Moral Portrait of Jews, Paris, 1940.

Only one thing links the names and texts I just listed: it is an obsession to recognise and identify. Even the language used legally to describe such identifications and classifications exhibits the optimistic and procedural character of this obsession; it is always something that has to do with a process, with a trial, in a sense, a procedure, in which you can read an inexorable movement to pin the other down.

Instead of that, I think it is preferable to subscribe to the notion that knowledge of the other, becoming acquainted with the other (instead of recognition, which brings everything back to pre-existing schemes) occurs in an almost static way, beyond all expectation.

The Work of Art in the Age of its Mechanical Reproduction, published by Benjamin in 1936, is too well known for me to dwell on it here. I will limit myself to one aspect I am particularly interested in today and which I referred to earlier, the discussion of aura.

With mechanical or technical reproduction of images, you lose what is authentic, you lose the connection to a particular time and place. The photographed or filmed object is abstracted from tradition, it moves closer to the viewer, and by doing so it loses it sacred character and its aura. “We define the aura as the unique phenomenon of distance, however close it may be…Whether we are talking of works of art or natural objects”. Photography removes from objects their cult value or cultural function. But, Benjamin adds,

…cult value does not give way without resistance. It retires into an ultimate entrenchment: the human countenance. It is no accident that the portrait was the focal point of early photography. The cult of remembrance of loved ones, absent or dead, offers a last refuge for the cult value of the picture. For the last time, the aura emanates from the early photographs in the fleeting expression of a human face. This is what constitutes their melancholy, incomparable beauty.

If I follow him, I see that photography stands out in a special way. While separating the object from its cult value, photography also furnishes a cult object, which is the human figure. It gives us visual traces and signs, optical hooks, so to speak, which allow our “cult of remembrance of loved ones, absent or dead”, to expand. (I don’t subscribe here to the Benjamin’s distinction between “early” and “modern” photographic images. I guess that it depends on his need of being faithful to his idea of the aura as “glance of the obsolete”).

However, this cult is embedded in the very notion of resemblance and proximity to the object that has moved away from us. Aura, then, is what is absent from the image but what inhabits the space between us and the reproduction, and therefore aura is what allows the relation and not what keeps the object unique and distant from us. So, the photography can be holder of an hidden content. We are able to catch “also, through the reproduction, what is unique” (A short History of photography, 1931).

Following Bataille, photography’s crime is the visibility itself, is verisimilitude, resemblance, excessive closeness, contamination by kinship; all these things dictate the banality of photography’s evil, its monstrosity (“monstrosity without madness”).

For Benjamin, the aura is lost and found again in the fleeting expression of a human face; it is found in the instant of taking the picture, in a moment of social identification given by this image, and in which the light arrests the time.

It is easy to see, then, that a similar photographic document can be monstrous for one person and “incomparably” beautiful for another. The former rejects it in the name of the “irreducible ego”, and the latter admires it because of the short-circuit in distance and kinship, in loss and identification. He doesn’t ask it to be “true”.

Benjamin says that these images are beautiful because they are melancholic. Beauty here is a matter of emotion. this emotion has to do with mourning. In the age of photography, mourning and the cult of the dead have replaced the cult of gods. Bataille rejects the cult of the dead and he rejects any pious image that pretends to represent the dead. There isn’t any sacredness in the technical image.

In the name of the identification with the past, the distant past in some other place, Benjamin finds an aura in photographic reproduction. To copy, to transcribe, to translate, to adhere to a distant object, to tradition, those are his joys. To draw, to map out the places, to trace in the dusty ground the names of old loves, rewrite the story of one’s childhood, retrieve past times, also.

I see the snapshot, in this context, as the point in the telegraphic communication; it is necessary to the comprehension of the text, which is a line in time. For Bataille, the flash cannot be followed by any trace; it is just an instant. No past, no future. Just acceptance.

Fall 1993