Mario Rigoni Stern (1921-2008) had two ‘anabasis experiences’ in his lifetime. The first one involved the retreat of the Italian Expeditionary Corps in Russia, in January 1943. Rigoni was one of the 60,000 ‘Alpini’ elite military corps that Mussolini sent to occupy the Soviet Union, and among the fortunate 20,000 that returned home safely. His second “anabasis” experience occurred two years later, during his escape from a German military concentration camp in April 1945. For ten days, Rigoni wandered through the Styria and Carinthia forests in Austria surviving on berries, bird eggs and snails before encountering an outpost of Italian partisans at an Alpine pass.

I regard Mario Rigoni Stern as one of my spiritual fathers along with Nuto Revelli (1919-2004) and Vittorio Foa (1910-2008). Among the three, it is Rigoni Stern who explored in greatest depth the relationship between humans and their natural environment. The theme of the forest, as a locus of nature, is central to Rigoni’s oeuvre. The pre-Alpine forest, which was completely destroyed by Austrian and Italian bombs between 1915 and 1918 and subsequently replanted, is an example of the blending of the artificial with the natural. By the time Stern’s work Uomini, boschi e api (Men, Woods and Bees,) was published in 1980, the Asiago plateau forest had reverted to a nature state.

The forest is a mirror of the world “as it should be”, a world where “siamo tutti compaesani”, (we all belong to the same village). In this ecosystem, we can all live together, humans and various animal species, once the carrying capacity of the environment is under control. But according to the writer, the ‘good’ forest is not the one that grows freely and spontaneously. Rather it is the one tamed by human labor, where humankind plays the role of the caring gardener.

At the beginning of his book Forests. The Shadows of Civilization, (Stanford 1992), Robert Pogue Harrison quotes the Italian philosopher Giambattista Vico: “This was the order of human institutions: first the forests, after that the huts, then the villages, next the cities, and finally the academies…” (The New science, 1725). But Vico’s text continues as follows: “it is the nature of peoples to be first crude, afterward severe, then benign, later on delicate, eventually dissipate”.

Rigoni Stern considers Vico’s reflection, and assumes that the city (the last stage of human progress before academies, according to Vico) has become a place of “spiritual solitude”, where “barbarity dwells in the very heart of the humans” and states that the woods have become a “place of salvation” (Introduction to Boschi d’Italia, Rome 1993).

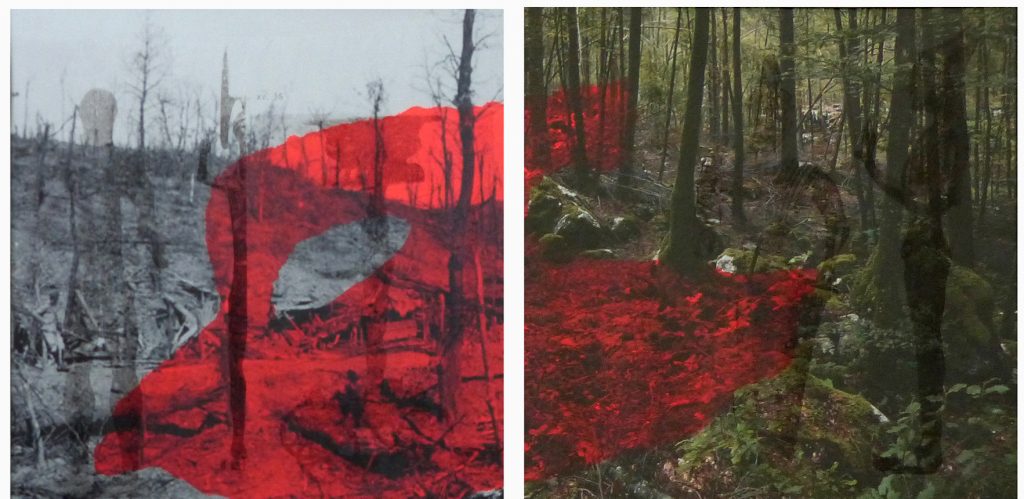

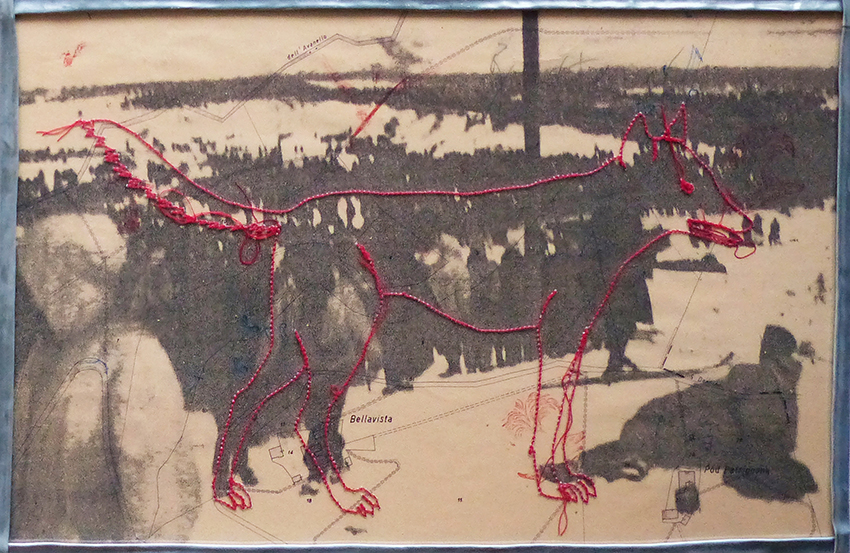

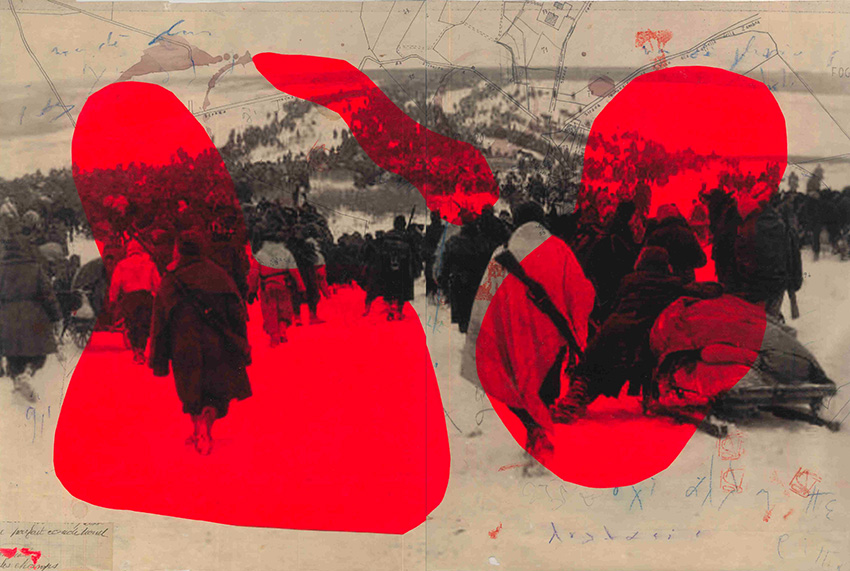

As I wandered around Rigoni’s homeland, I recorded some images of forests, which, upon closer inspection, reveal traces of the war: the collapsed trenches and the craters left by bombs. There I encountered a theme related to my Rupestrian series: these sites have also been reclaimed by nature, even if here the traces left behind are the result of humankind’s diabolical engineering rather than its creativity.

The works that bears the title Anabasis come from the superposition of these images and archive images: the Alpini retreating in the Russian snow, the trenches and the woodland of the Asiago plateau after an artillery battle.

Anabasis 03, 40×60, 2015.

.

Anabasis 06 A and B, 30×30 each, 2015.

.

Anabasis 09 B, 40×60, 2018.

Anabasis 09 B, 40×60, 2018.

.

Anabasis 08 B, 40×60, 2020.

.

Anabasis 05 B, 40×60, 2021 (2015).

Anabasis 05 B, 40×60, 2021 (2015).

.

Rigoni Stern connut deux anabases, une grande et une petite. La première fut la retraite de Russie, en janvier 1943 ; Rigoni était l’un des 60.000 chasseurs alpins italiens partis pour occuper l’Union Soviétique, aux côtés des allemands, et il fut l’un des 20.000 qui en revinrent. La deuxième fut sa fuite solitaire du Stalag, en avril 1945 ; pendant une dizaine de jours il erra dans les forêts de Carinthie et de Styrie, se nourrissant de baies, d’œufs d’oiseaux et d’escargots, jusqu’au moment où il rencontra, sur la route des Alpes, un poste avancé de partisans italiens.

Mario Rigoni Stern (1921-2008), avec Nuto Revelli (1919-2004) et Vittorio Foa (1910-2008) est l’un de mes pères. Et, parmi mes pères, c’est celui qui a le plus investi la thématique du rapport de l’homme à la nature.

Le haut-plateau d’Asiago est le lieu des origines et des retours de Rigoni ; la forêt qui le couvre, cette même forêt annihilée par les bombes autrichiennes et italiennes entre 1915 et 1918 et ensuite « reconstruite » (exemple du naturel qui devient artificiel, pour redevenir naturel) est un sujet central dans son œuvre littéraire.

Le bois est, d’après Rigoni, « lieu de salut » (introduction à Boschi d’Italia, Rome 1993), tandis que la ville est devenue le lieu de la « solitude spirituelle », où « la barbarie se cache jusque dans le cœur des hommes ». L’écrivain de l’Altopiano reprend ici les arguments de Giambattista Vico (Principi di scienza nuova, 1725), tout en leur donnant une inflexion plus humaniste et, somme toute, réconciliante. Si l’homme veut survivre « avec » la nature, il doit être capable d’en prélever sa part, sans en entacher le capital.

Comme on le sait, Rigoni était un chasseur passionné ; on se demande si, finalement, ses raisonnements ne couvraient pas son désir de s’adonner à la chasse au coq de bruyère. Cela dit, le coq de bruyère n’est aucunement en danger et la forêt se porte bien en Europe, vu sa progression aux dépens des pâturages et des terres cultivables.

Aussi éloigné d’un sentiment de domination inspiré de la civilisation des Lumières que d’une approche nostalgique à la Sturm und Drang (1), Rigoni exprime plutôt un sobre panthéisme humaniste ; la « bonne » forêt n’est pas, d’après lui, celle qui pousse de manière spontanée et sauvage ; c’est celle qui est administrée et ordonnée par l’homme, en sage jardinier.

En errant, en touriste, sur l’Altopiano, j’ai enregistré quelques images de sites naturels où restent visibles les traces de la guerre : les tranchées écroulées, les cratères ouverts par les obus. Je retrouve, dans ces images, le motif de mon travail sur le rupestre : peut-on parler de sites « rupestres » même si ce n’est pas la créativité de l’homme qui a laissé ses empreintes, mais plutôt sa diabolique ingénierie ?

Les travaux qui ont pour titre Anabasis naissent de la superposition de ces photographies et d’images d’archives : la retraite des Alpini dans la neige de Russie et leur lutte pour s’ouvrir un passage ; les abris des fantassins et les bois de l’Altopiano éventrés par les batailles d’artillerie.

(1) Sur la confrontation-opposition entre ces deux courants de pensée voir Robert Pogue Harrison, Forêts : Essai sur l’imaginaire occidental, Paris 1994.