Steles of Anamnesis, 1994-1995.

La civilisation du phoque, 1994-1995.

Ninna nanna, 1995

Les Ames du purgatoire, 1995

Anabasis 1995

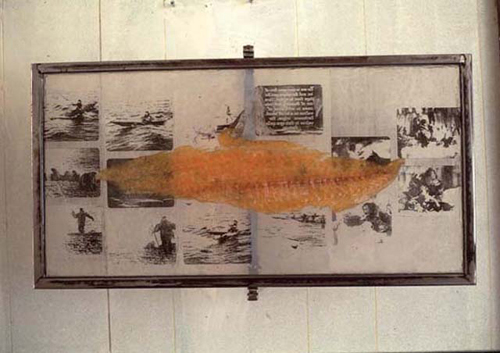

Nanook Sequence 1996

Cranial Nerves, 1996

Still Lives, 1996

Boustrophedon 1997

L’art de la guerre, 1997

![]()

Iconostasis, 1997

Leçons d’anatomie, 1998

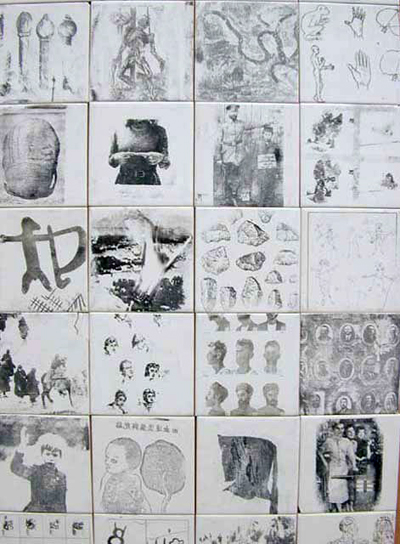

Kinderatlas, 1998

Wilderatlas, 1999

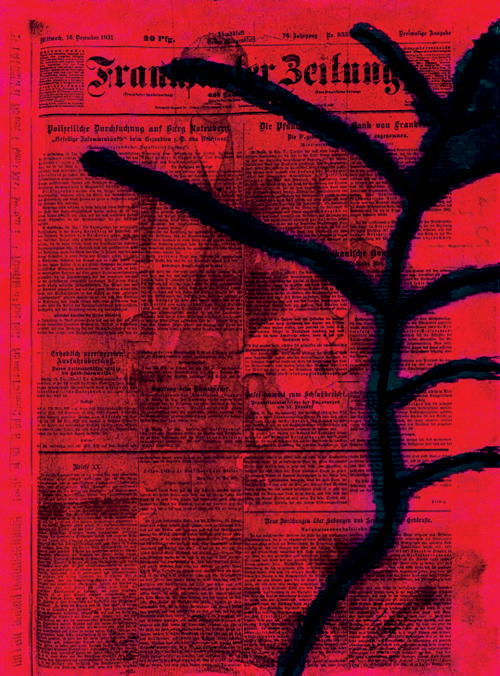

Skyggerids, 1999

1930 circa, 2002

Inventarium, 2004 (detail)

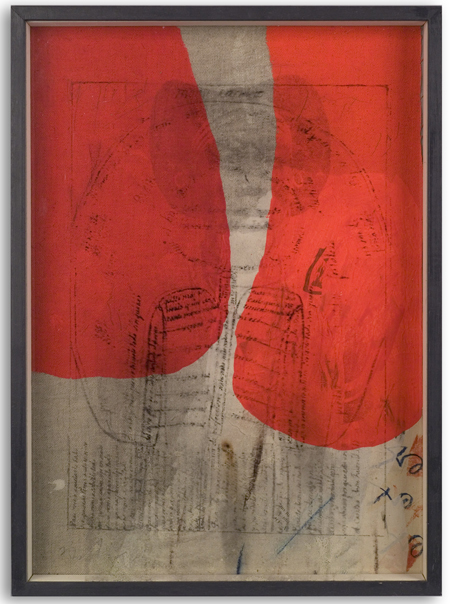

Ex voto, 1990-2006

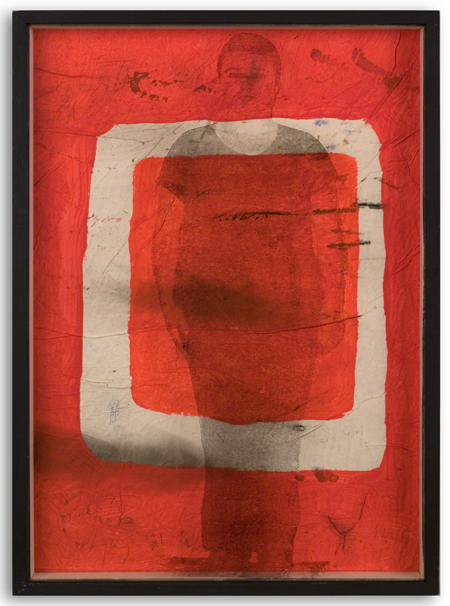

Monte Carmelo, 2009

La Buoncostume 01, 2009

La B-C, 2009

L’Illustrazione Italiana ter, 2009

My artistic activity over the last years has focused on our common historic heritage. More specifically, I have endeavored to elaborate an iconographic program that enriches and skews our perception of “our” family portraits. To achieve this objective, I have collected archival material, scientific diagrams, administrative documents, as well as police mug shots and plates from anthropological studies. From such material, I have created new images. The work I have undertaken in recent years involving collages created from original documents mixed with painting naturally led me to attempt to develop a ‘photograph of history’.

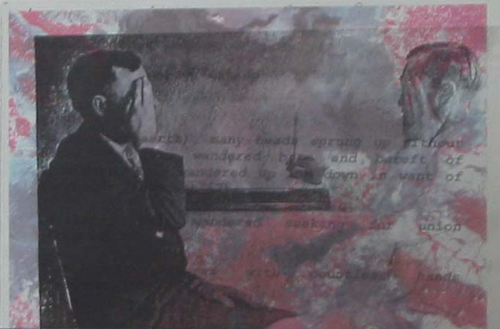

Considering photography solely as a method of reproduction – i.e. its most restricted function — I have used it as a fragmented piece of “evidence” in large-scale articulated works, which were not intended to propose new meanings but rather to call into question our manner of regarding the past. The images I exposed were often mutilated and reduced to fragments, which prevented the viewer from imagining the whole that could be constructed from these fragments; they were sometimes rendered illegible by the superimposed layers of documents and iconographical material.

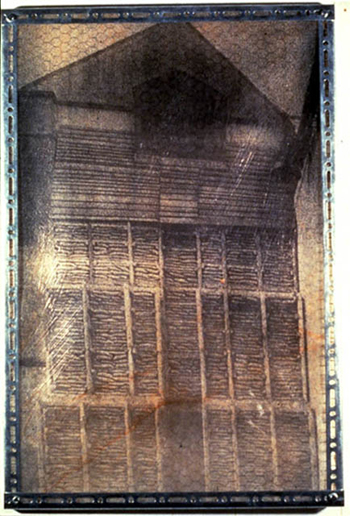

Using cut-up X-rays as screens or filters, I created a play of shadow and light, and transparency and opacity on the images. As both an abstract reproduction and a negative image of the hidden reaches of the body, the X-ray is itself a form of body writing – a recording that must be deciphered and interpreted. The transparency of the X-rayed body forces the viewer to reflect upon the impossible permeability of the photographed image. How can we pierce and destabilize its forms that are so saturated and definitive?

I have thus reproduced ‘our’ photographs on a support of sheets of transparent film. I superimposed them on completely unrelated photographs or on some of my earlier works that I have cut up and repainted. I then enlarged details to the point of rendering them abstract and hid them behind metal grating — a reference to pre-grammatical signs. I mounted them between two glass plates in metal structures that distanced them from the wall, thereby allowing any light source to transform them into shadows, which could be deformed or deformable according to the angle of the light source and the orientation of the frame.

By incorporating shadow in my work, I have reverted to the earliest form of image making, which, according to myth, was born from the contemplation of shadows. Using industrial supports typical of our period, such as transparent films, gelatinous material and florescent colors, I intended to shed the original icon of its solemnity and aura so as to present only a facsimile.

In addition, these materials allow us to ‘sublimate’ a mundane subject or to trivialise a pretentious subject. Perhaps this is a manner of getting around the question that has traditionally troubled all visual artists: the inadequacy of any given subject matter.

Reproduction functions as a conservation tool, yet this necessarily implies a loss. The original image having been at any rate lost, we, the viewers, are left with infinite possibilities to recreate it in our own imaginations.