When I was a boy Antiquity was an amphora mouth on a sandy seabed not deeper than three meters. I would approach it with a trident in my hand and, at the top of it, a white tissue. Octopuses are attracted by white things and get out of their favorite burrow to attack the piece of fabric; this is the moment for harpooning them. It is a simple and fruitful submarine hunting technique.

I must have been fifteen or sixteen. The waters were those of Porto Clementino, on the shore of Tarquinia. I had not yet seen the painted tombs.

Once I took up a big cephalopod still grasping its terracotta dwelling and, when somebody told me that a guy was ready to pay up to twenty thousand liras for an intact Roman amphora, I moved further away. In front of Pian di Spille military camp, I found, at a depth of about six meters, several vases of the type Dressel 1A or 1B. With a rudimentary winch, made out of a line and a rubber roll, I could recover them by myself.

The following winter I hired a motorcross bike and together with a friend I would ride on Sundays through the abrupt countryside around Blera exploring Etruscan tombs. We were never the first ones to enter although this did not prevent us from finding fragments of a black bucchero or of a painted vase.

In February 1971 an earthquake struck the little city of Tuscania. With three friends we went to give a hand having taken a shovel to help digging.

We would sleep in army tents and warm up in the evening with the 50° weird alcohol the soldiers would generously give us. During the day we would dig out the old borgo obstructed streets; occasionally we would enter an abandoned apartment: family photographs spilled out of shoe boxes, knickknacks, doilies and lace covered with dust and rubble.

I then saw Etruscan sarcophagi lined up around the walls of the city hall square along with their decapitated statues: it was the work of the tombaroli. I also saw the mutilated apse of the most beautiful church in the world, the Romanesque basilica of San Pietro (I wonder now whether that is a real memory or the result of various condensed images since I visited the destroyed churches also in Irpinia, also affected by an earthquake in 1980).

Later on during my university years, I had chosen a degree in Etruscology, which came to an end with the requirement that I pass a German language test. These were also the times of the student movement; its assemblies looked rather like a boxing match: on one side there were me and my fellow students who belonged to the friends of the “revisionist” newspaper Il Manifesto, and on the other the “Sturmtruppen” of the Autonomia Organizzata.

After the university period, I moved on to other things but I always went back to the tombs of Tarquinia. I could say that I visit them more than my parents (hoping they won’t detest me for that). I went there when they were all accessible (open) to the public; then, when they were opened only on an annual rotation (the breathing of the tourists and the variations in humidity and temperature being very damaging for the paintings) and eventually now that they are visible behind the double glass that seals off their entrance.

And I must here admit that, whenever I am back in Tuscia, I tend to leave my wife and children in the car while I rush out only for a few minutes in order to see one or two of them.

The British writer D. H. Lawrence (1885-1930) visited maybe two dozen Etruscan sepulchers of the Monterozzi necropolis during two days in April 1927. He describes visiting fifteen of them (see Etruscan Places, posthumously published in 1932). It is on that occasion that he points out the idea of a Etruscan joyousness and hedonism opposed to the Roman austerity and militarism; an interpretation that would support his polemics against Mussolini’s regime, which saw itself as the heir of the powerful Romanitas.

I will here describe a few of these painted tombs in my own way.

Tarquinia B 01. On the threshold of the Hunting and Fishing cubicle an Inuit poet gives rhythm to his duel song with the sealskin drum, while the two Ayakutok co-wives laugh before the William Thalbitzer photo camera, at Ammassalik, in Summer 1903. A young Etruscan hunts birds with a sling, another one jumps from a rock into the sea. “Here is the real Etruscan liveliness and naturalness”, Lawrence would say.

Tarquinia B 02. The two multicolored Charun that watch the underworld door have found companions: a few Ainu, members of the ethnic minority that dwells on the Japanese island of Hokkaido. The wise anthropologist who measured them in 1929 (later author of the useful booklet How to recognize and explain the Jew?) ended up shot by the French Resistance and surely finds himself in the circle of the collaborators.

Tarquinia B 03. Inside the Lionesses crypt a party is noisily taking place: people orgiastically dance, play the double flute, drink stirring beverages. Dolphins dive into a grey sea, while a Greenlander hunter stands beside the hole he dug into the ice. Soon a seal will approach to take a breath. On the right wall of the sepulcher a bleached blonde reclining man “holds up the egg of resurrection”.

Tarquinia B 04. In the chamber of the Lotus flower Hopi warriors perform their traditional dances before Aby Warburg, in New Mexico in 1895. On the opposite side of the Americas a Ona youngster from Patagonia fixes up his headdress before accomplishing the phallic ritual before the missionary and photographer Martin Gusinde, somewhere in the early Twenties. The bare wall presents a proper backdrop.

Tarquinia B 05. The tomb of the Hunter is decorated like a hunting lodge; a row of lions, bulls, deers, dogs and riders tread on its walls. In such a space several types of Chinese are gathered. They show their faces and profiles, but are not so recognizable: the squared pattern of the ceiling and the colored dots on the sides mix up their outlines. After all: aren’t we all equal, down there, humans and animals alike?

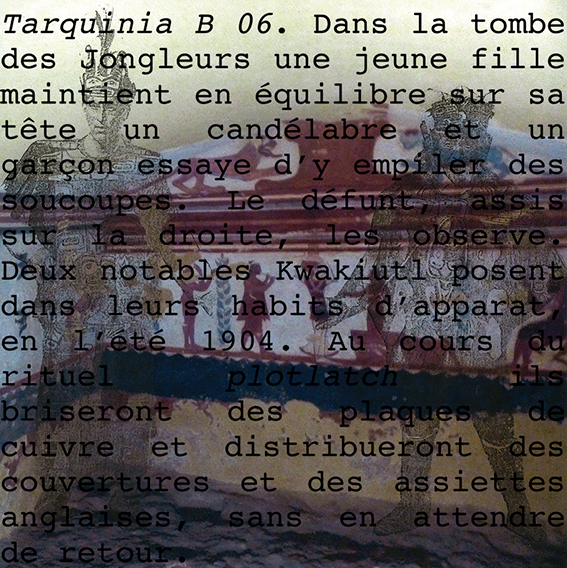

Tarquinia B 06. In the tomb of the Jugglers a girl holds upon her head a candelabra, while a young man is trying to pile up on it some little discs or plates; the deceased is sitting on the right-hand side and is observing them. Two upstanding Kwakiutl men are posing in their ceremonial dresses, in summer 1904. They are preparing the potlatch ritual, where they will break copper shields and distribute English blankets and plates, without waiting for a payback.

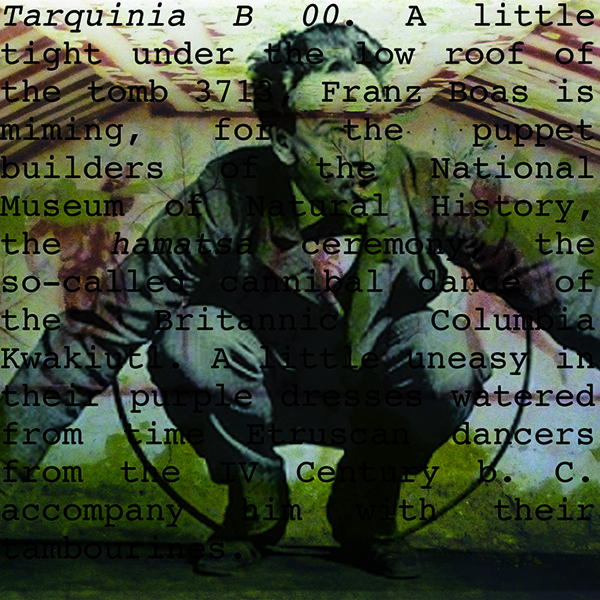

Tarquinia B 00. A little squeezed under the low roof of the tomb 3713, Franz Boas is miming, for the puppet builders of the National Museum of Natural History, the hamatsa ceremony, the so-called cannibal dance of the British Columbia Kwakiutl. A little uneasy in their purple dresses washed out with time and oblivion Etruscan dancers from the IV Century b. C. accompany him with cithara and tambourine.